99% Invisible is one of my favorite podcasts. It’s about “the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world,” to quote from the show’s website. Each episode makes me take a closer look at the houses and highways and all the other human creations that we have built around us.

I recently reached out to the host Roman Mars about my new book AIR-BORNE. That might seem like an odd move, given that my book is about the life of the air—the pollen and fungi that soar across oceans, the bacteria that eat clouds, the trillions of insects that fly in invisible rivers thousands of feet above the ground, and the floating viruses that can unleash pandemics.

But one of the messages of my book is that the air is a common good. We all have to breathe it—and everything in it. And the air is composed partly of our collective breath. We can make the air safer for everyone by recognizing how we shape it—in part, by living in buildings in which dangerous pathogens can build up in the air like smoke.

Mars was kind enough to have me on the latest episode of 99% Invisible for a conversation about our intimate relationship with the air, and how to design it to be a healthy one. You can listen to it here.

This month I also talked about AIR-BORNE on BBC’s Instant Genius and TaleWind.

The Cluttered Code

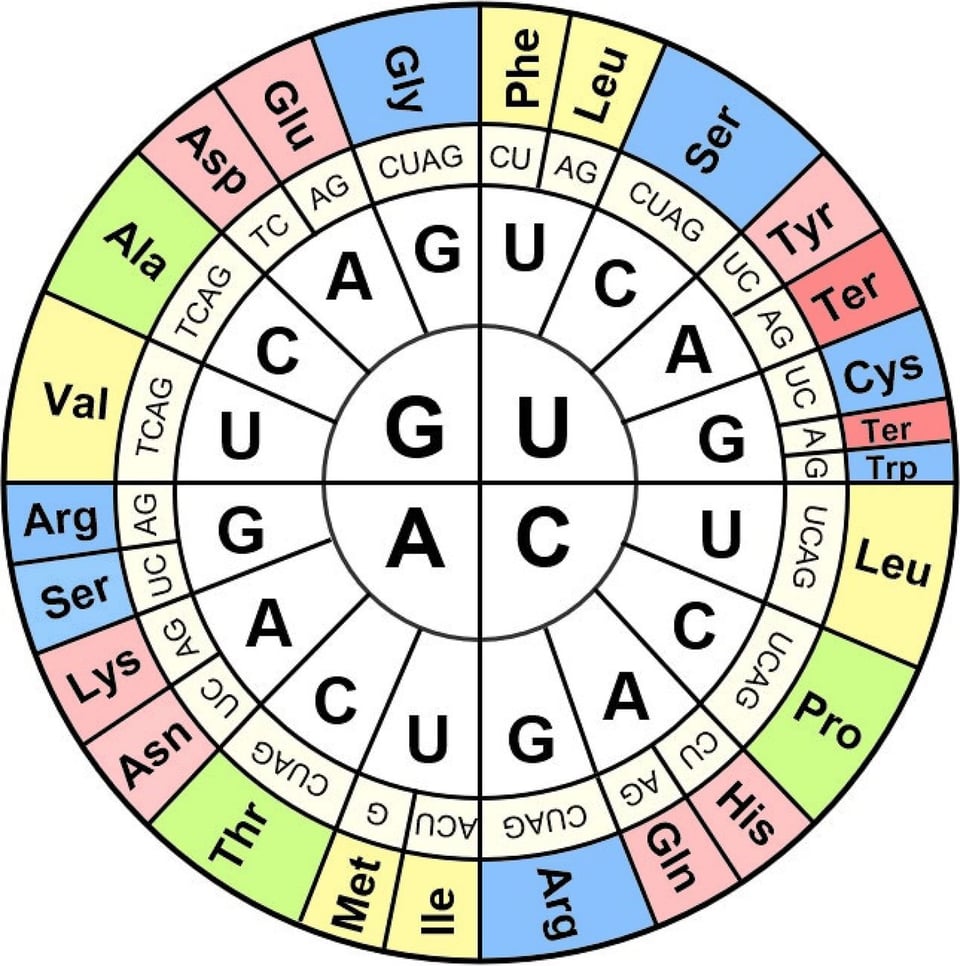

The double helix of DNA has become a modern icon of life—the elegant spiral-staircase of a molecule that encodes the instructions for biology. But for me, this weird wheel is just as iconic. It's the genetic code: the rules by which our cells translate the four-base alphabet of DNA into the 20-amino-acid alphabet of proteins.

Whereas DNA is sleek, the genetic code is overstuffed. Some amino acids are encoded by two different sets of bases, some by six. And this strangely redundant code is universal—basically unchanged from one species to another.

The history of how scientists discovered this odd code is fascinating. I wrote about it for Nautilus some years ago. For more on this history, I’d also suggest you watch Matthew Cobb give a lecture at the Royal Institution about his book, Life’s Greatest Secret.

But the genetic code isn’t just the stuff of history. It also makes news. Over the past decade, scientists have been trying to understand the genetic code by making new ones. They are synthesizing DNA to build new genomes that don’t use some standard codons. I wrote a story in the New York Times today about their latest creation.

Instead of the 64 codons found throughout the living world, British researchers engineered microbes with only 57. If life can get by with 57 codons, then why is the universal code so much bigger? Check out my story for some possible answers.

In addition to the genetic code, I also wrote this month about ancient reptiles with not-quite-feathers, some disappointing results in the search for life on other planets, making AI behave the way minds really work, and a 37,000-year-chronicle of the germs that have made us sick.

Hiding and Dismantling

The future of science in the United States has reached a summer of uncertainty. The White House has proposed cuts that would, experts agree, be devastating. Now the budget is bouncing between the two chambers of Congress. The Senate, at least, has put forward proposals of its own that would largely keep support to agencies like the National Science Foundation unchanged. Congress has also indicated that it doesn’t want to drastically reduce so-called indirect costs, the funding that supports the infrastructure that makes science possible. We won’t know how it all shakes out until this fall.

But even without a final budget, the Trump administration continues to wreak havoc on science. To pick just one recent example: the Environmental Protection Agency plans on rescinding a 2009 finding that links climate change with harm to public health, essentially stopping the government from doing anything about global warming.

Not coincidentally, the government has been erasing online information about the reality—and risks—of climate change. It’s information that hundreds of climate experts have worked for years to assemble.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has been posting information of its own online. When the EPA announced that it would be abandoning climate change, it cited a newly released report from the Department of Energy billed as “a critical assessment of the conventional narrative on climate change.” The authors—five well-known contrarians—cite a lot of their own papers. Reporters reached out to other scientists they cited as they cast doubt about the risks of climate change. Guess what: those scientists say that the assessment distorts their work.

“This whole thing is just incredibly disingenuous and not an accurate depiction of the field,” one said.

That’s where we are. Stay safe.

You just read issue #194 of Friday's Elk. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.