Thoughts on Django’s Core

To tie-in with the upcoming elections for Django's Steering Council, I wanted think again about Django's Core, let's call it Batteries Included Revisited.

Django’s surprising longevity

Django will be 20 years old next birthday 🎂 — I don’t think I’m really going out on much of a limb to say it got an awful lot right.

“The web framework for perfectionists with deadlines” — If I had to call out things that are the cornerstone of that, I’d probably point to the request-response cycle, the ORM (of course), and ecosystem of third-party packages, of which DRF stands out as the package that was simply essential for so long.

Likely, if I asked you Why Django?, you’d point to similar things. Maybe we’d quibble on details. You’d emphasise one thing, I another. But likely the tone would be, ”Oh, yeah, that too”, rather than disagreement per se. The answer is always some variation on, it lets me do my job.

But it wasn’t always clear that Django was going to make it to where we are today. There are plenty of good projects out there that don’t make it into maturity. Django is not the only way you can solve the web problem quickly.

If we look back a decade, Django 1.7 was being released, and migrations were being added, as Andrew Godwin’s South package was merged into core. This was a high-point, but several things stand out.

The original generation of maintainers had largely stepped back, there were fresh faces, and several of them, but they too would, in time, drift away until almost Andrew Godwin — who led Django’s async effort — was the last person standing there.

Apart from that async effort — the DEP for which was approved in July 2019 — if we look at the release notes for the subsequent versions (1.8, 1.9, 1.10, …) there are masses of improvements each release but, there’s a radical shift towards the smaller incremental changes that we’ve become used to over the last number of years.

At some point along the way, the old Django Core Team stopped admitting new members, so as folks drifted away it became stale. (It was this that led ultimately to the effort to bring in DEP 10, which sought to disband the old Core Team and bring in an elected leadership for Django.)

There was almost a presumption that Django would close-up shop one day. I remember going to DjangoCon US in San Diego in 2018, in my first year as a Django Fellow. I gave a call to action in my short Your web framework needs you! talk — arguing that we needed to be more dynamic in addressing Django’s ticket backlog if we were going to progress — but vividly remember a conversation with Frank Wiles, who was DSF President at the time, about the DSF budget was explicitly set to make sure that Django could roll-up gracefully when the time came.

And then came COVID, which brought a massive break in community continuity, that I think we’re only just fully recovering from now.

As we stand here today, things look different again. The community is enthused. There’s a whole new wave of people invested, and often, the new folks are bringing back the old. There’s a real appetite now to push Django forward once more.

But Django, like so many other projects that didn’t make it, could have easily died in the intervening years. As we look into the future, it bears thinking about why it didn’t?

Django’s secret weapon

The triumvirate that bought the space for Django to mature is its time-based release schedule, the API Stability Policy, and the Django Fellowship Program.

The time-based release schedule — which dates from 2015, exactly when we see that shift to incremental releases — means that releases go out automatically. There’s no need for decisions to be made about them. What goes in is what’s ready. This enables Django to progress almost without leadership if it needs to. The incremental changes come in, but a release is never held-up (indefinitely?) because the headline feature wasn’t ready yet.

The API stability policy means that breaking changes aren’t introduced without going through the deprecation process. It means that updating Django doesn’t break your code, and it’s led to an almost cultural shift in the ecosystem.

Old-timers love to tell war stories about updating Django. It used to be almost a badge of honour as to who was running the most outdated version in production. In contrast, now, updating is largely painless, and it’s expected that you’ll be on a supported version of Django, with its security fixes and everything else that that implies.

That combination, of regular releases and ease of update, is what’s kept people (kept businesses) on Django, and it’s what has brought them back to it. That constant stream of new features add up over time, and combined with reliable releases, it’s a hard offer to resist. Whereas a decade ago, a Django release would bring criticism and any number of hot takes about Better Tech™ that you should be using, these days it’s overwhelmingly that Django is a solid choice, that keeps on working for you. Django has become a default option — boring tech, in the very best sense of that term.

The Fellowship Program is the third-leg that makes that work. The Fellows are Django’s stewards — when I was a Fellow, I would jokingly describe it as being the janitors — they handle the incoming issues, keep pull requests progressing, so those features keep coming, defend the stability policy, to make sure the new version doesn’t break your app, and roll those releases, like clockwork.

The release schedule and the API stability policy set the framework, but the Fellows are what make it happens. Without them, Django would have died. The work wouldn’t have been done. The issues would have piled up. The releases would have stopped. There is no doubt about that.

And it’s still the case today. If the Fellowship Program disappeared, Django would be lucky to make another major release. That it could make two is unthinkable.

I doubt that’s an exaggeration. So let’s remember it.

More? Into Core?

So, that’s all background. As we stand here now, there’s a new head of steam, a new energy for pushing Django forward. Our challenge is: How do we do that?

Over the last month or two, there have been several posts about what we should or could add into Django. What batteries should be included? What features should we have?

The specifics don’t matter here — there’s nothing that’s make or break. There are plenty of good ideas, and, modulo the thoughts below, I’m pretty maximalist: Let’s have it all!

Recently, though, I’ve been arguing that Django has a grain. People have joked about me saying this, so I’m hoping the message is getting across: Django wants you to do things a certain way, and my contention is that the more you do that, the happier you’re going to be.

As soon as we start talking about adding features to Django, though, we hit right on a pain point that folks struggle with again and again.

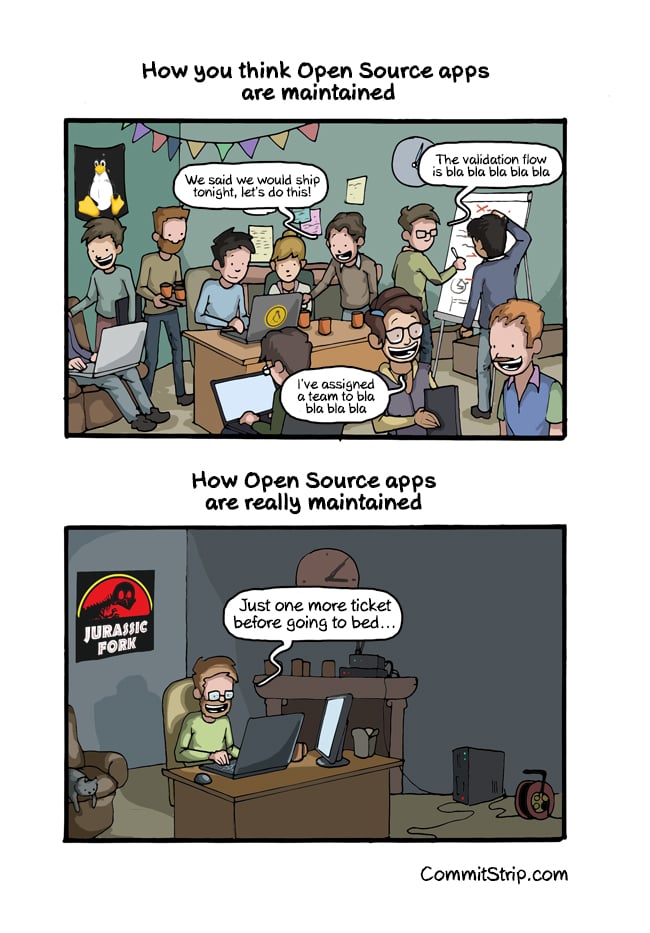

I'll throw in an image from a toot that made me laugh when I saw it:

It’s difficult to get features into Django. For all the reasons for Django’s success, it goes right against the grain, and — my concern is that — if we’re not realistic about that in the upcoming cycle, we’ll waste a lot of our built-up energy. In contrast, I’ll argue, if we go with the grain — if we do things the Django way — there’s no real limit to what we can get done.

It’s not a murder mystery, so I’ll tell you the conclusion now. It’s long been Django advice that new features are experimented with in third-party packages. If we want to move fast, we need to double-down on that, and focus our efforts on the social problems that leave Django the framework isolated from its ”secret sauce” third-party ecosystem.

Despite the ecosystem of third-party packages being one of the cornerstones of Django’s success — that “secret sauce” quote is from the old Two-Scoops of Django book, first published for Django 1.5 — folks often feel deeply that that’s not enough for their feature. I think the social problem is the key one here, but let’s pause to consider the counterfactual.

Let’s say we try to add everything suggested into the core. It’s here that we’re going to hit up against Django’s grain. There’s a natural bias always pushing us in the other direction.

Capacity Planning

Taking the smallest examples that always come up: Can we add this template tag? Can we add this database function?

They’re only simple, agreed. Individually they add little burden. But it adds up over time. Line by line, test by test, doc by doc, slowly but surely Django accretes mass, becoming ever harder to maintain as it does.

People think Django is a big org. The truth is, it is anything but. Here a Commit Strip cartoon that we used to post as a Periodic Reminder for folks on the DRF issue tracker:

There are currently 954 open accept tickets on Django. There are currently 260 open pull requests on the Django repo. We have two Fellows, one of whom is part-time, so 1.5 full-time Fellows to work on all of those, as well as doing releases, security report handling, and community work.

It survives. Just. It’s more or less stable. Just. But there is approximately zero additional capacity to expand.

Hire us another Fellow and we can talk.

Get community members doing a significant amount of triage and pull request review (to the point where PRs are fully ready to merge) and we can talk.

But short of that — at danger of collapsing the very effort that keeps Django alive, we remembered — the conversation naturally leans to keeping Django’s scope stable, or even having less in core, rather than seriously considering every suggestion for inclusion.

By keeping things out of Django itself, we spread the load. We boost the capacity almost without bound — there’s just as much capacity as there are ideas worthy to implement.

The stability policy revisited

More though, I promise you, core isn’t where you want your feature to be anyway. Will and I were interviewing Hynek Schlawack for an upcoming Django Chat. We were talking about the Python standard library, and he said:

The standard library is where packages go to die.

Put Django Core in there, rather than the standard library, and he couldn’t be more right.

Django’s release cycle means that you need to wait 8 months for even a bug fix to make it into your feature once it’s merged into core.

The API stability policy means that if you want to make a breaking change, you’re looking at two whole years to get that in.

That’s not where you want your package to be, not until it truly is finished, and even then… You would like to be able to fix the bug, and get the new version out that day, that week. You want to be able to take the feature request, and ship it to users now.

Not being in the core is a superpower. We want to embrace it.

§

There is a draft DEP to allow Experimental APIs in core.

Let's push this forwards, but it’s important to see that it doesn’t mean experimental in the sense that we’ll suddenly merge features that we’re still unsure about.

Rather, the idea was to allow features that are nearly complete to be merged in a .0 and .1 release, allowing that we might discover issues needing an API tweak before they’re settled. The point was to allow that change without requiring the full deprecation cycle to play out.

Note though, features were still to remain API stable for a given major release, so an experimental feature merged in 6.0 still couldn’t be updated until 7.0 (two years later).

To wit: “to have got as far as an experimental feature in the main codebase it should have passed a certain quality threshold and the DEP process and already be somewhat fully formed”.

The sense in which we need to be able to experiment on new ideas, isn’t the one in play here.

Example: Django Tasks

Does that mean we add nothing? Clearly not. There’s that steady stream of new features every release. But we can add bigger features too.

Django Tasks is a good example to consider here. This is a major feature that is going into core to add background tasks to Django — something that folks have long needed to use Celery and similar to achieve.

Adding tasks will undoubtedly add to the maintenance burden, but a couple of points show that it is not unbounded.

First, most of the work is in defining the task interface that backends can implement. Django then defines the contract, but the implementation remains someone else’s responsibility.

Second, the complex DB backend is first being implemented as a third-party package. It’s available to test and install now. The reality is there will be a good testing period in the community before there’s any rush to merge it to core. Only when we’re sure that the bugs have been washed out is there any need to tie it to Django’s long 8-month release cycle.

Batteries Included Revisited

Still, though, when Django says that it’s better to create a third-party package first, folks aren’t satisfied. There’s still that urge to want your feature in core.

I think there’s two-sides of the same coin here, and they come back to those social problems that I’ve mentioned (in bold no less) a couple of times already.

On the negative side, it can feel like being in an external package makes your feature a second class citizen — that it’s not as important or valued as a real feature.

So, DRF, django-filter, django-compressor, … — to name just some I’ve worked on… — I can’t express how wrong-headed it is (for us as a community) to allow an impression of being undervalued to thrive.

That Two Scoops line about the secret sauce, it continued:

The real power of Django is… the vast, and growing selection of third-party packages.

Pause a moment. The real power.

Simon Willison gave a talk about plugin architectures at the recent DjangoCon. He demoed a new plugin system for Django, but the key wasn’t the How; rather, it was the whole point of plugin systems themselves. They’re a force multiplier, letting your software gain new abilities without having to change at all. Well, third-party apps are Django’s plugins. The how of Simon’s new approach was different, but the what is just as it’s always been.

It often feels, there isn’t an idea you can think of that someone hasn’t worked up a prototype you can take inspiration from somewhere on the internet.

The core add-ons you need all exist, and are there waiting for you.

And there’s no way on Earth all of that could be maintained — even a fraction of it — if we did everything in the core.

The real power. The secret sauce. We should embrace and celebrate it. If we’re presenting third-party apps as second class citizens, even unintentionally, we need to address how we talk.

The other (positive) side of that coin is that Django is meant to be a batteries included framework.

For another upcoming Django Chat, we interviewed Bryton Wishart who picked up Django 3 years ago to build his business upon. Of course, we asked Bryton ”Why Django?” He gave two answers. The first was Django’s perceived reliability, that it just works, that we’ve talked about. The second was that it’s batteries included — that it comes with everything you need. (The specific example he gave was auth, with a familiar nudge that we really should have a two-factor story to tell in core by now.)

The big problem with steering everything to a third-party app is that there comes a point where it wouldn’t be true to say that the batteries were included. The batteries are on PyPI — Go find ‘em!

We asked Hynek about this, again, when we were talking to him. If everything is just on PyPI, how are folks supposed to discover anything? What’s left of the idea of being batteries included? His answer, which was casual, and we didn’t dig into because the conversation went elsewhere — so don’t go thinking it represents his considered option — was that people should subscribe to podcasts like ours, like Django Chat.

That works absolutely if you’re part of the community already. Between Django Chat, Django News, Awesome Django, Django Packages, and hanging out on the Forum, Discord, and Mastodon, you’ll see every package that goes past. A bit of searching, and maybe a raised hand, you’ll find what you’re looking for.

But that doesn’t work for beginners. It doesn’t work for the vast majority of the user base.

I posted recently about DSF Initiatives I'd Like to See from the new DSF Board, that’s currently being elected. I made the point that Django Chat, and by extension all those other resources, reach only about 0.1% of the Django user base:

Jacob Kaplan-Moss gave an estimate of the Django user base in his recent DjangoCon US talk. It’s in the single-millions. (The exact figure doesn’t matter here.) It’s no secret that Django News and the Django Chat podcast have subscribers/listeners in the single-thousands.

What that means is that we reach (to an order of magnitude) 0.1% of the Django user base.

If our solution to batteries included is that you have to listen to Django Chat (&co) then the danger is that Django is batteries included only for that 0.1% of people, which is to say it’s not batteries included at all.

I argued in my piece there that we need to integrate the Django community better with Django itself. The bottom line is I think we need to do the same thing with the ecosystem too.

“Framework < Ecosystem < Community”, right. Or that’s how it’s supposed to be. But both the ecosystem and the community are almost absent from the Django website.

We can make changes to Django’s core — we can add features — but many things are just better off as plugins, as third-party apps. The issue is that social one: that looking from Django, the third-party ecosystem is almost invisible. It’s our secret sauce. It’s our real power. And we don’t mention it at all. We neither do ourselves nor our wider user base any service.

Recharging the batteries

That head of steam we’ve got, that new enthusiasm? I’d have us carry on as we’ve been — incrementally improving Django — but use that new energy to address how Django can embrace the ecosystem, and so leverage it for all it’s worth.

We’ve got an asset, sat there, underutilised. As these things go, it’s an easy win to change that. It’s taking what we already do, and nudging it just slightly. It’s going with the grain of Django.

§

So, that’ the take-home. A couple of thoughts to wrap up.

Why hasn’t Django done this before?

It’s been a long-standing policy to not link to third-party packages in general. That’s a bit of a myth, in that there are plenty of things linked to, but the idea was to keep it down.

As an example, the recent release added a tutorial step showing the use of django-debug-toolbar, which is one of Django’s most established packages. DDT is among the top-used packages every year in the developer survey, and has solidly maintained for most of the life of Django. Jacob Kaplan-Moss blogged about it being one of his favourite packages in 2010! Even so, there was massive pushback against adding the tutorial step.

So, why is that? I think three reasons, all of which are valid, and all of which need to be considered when we’re looking for a route forward here.

Firstly, keeping lists of third-party apps updated is a chore in itself. (Ask the maintainers of the Awesome Django repo.)

Most packages don’t have anything like the stability of Django, even over the lifetime of a single LTS release. We can’t keep making tweaks to the docs — to older docs particularly — to keep everything fresh. Nor can we just let the Django docs house rotting links.

Quality above all else.

Then, we risk the danger of picking a blessed option that kills competition in the space.

A good example here is Django REST Framework. Long was there talk of merging DRF into core. Maybe if we’d have done it in (say) 2018 it would have been the right thing to do. But fast-forward to 2024 and there are new exciting options available — Django Ninja, with its Pydantic based schema, being the one with the most mind-share currently, I think. If DRF had been in core, it’s difficult to see how a competitor can pop up in the space. I’m not convinced they’re mature yet, but it seems clear that much more elegant serialisation options are incoming, and not having a blessed option encourages that growth.

The same can be said of template component libraries right now. It’s vibrant. Let’s not pick one and crown it. Let a thousand flowers bloom, and see what emerges.

Daniele Procida asked in the questions after my talk at both DjangoCons that I spoke at this year whether I thought we’d dodged a bullet with DRF (and similar). I think the answer is yes. Django’s small core, and slow merging process, mean we don’t get chained to the wrong solution.

HTMX is a good case here. I’m a big fan of it. I want (and I’m working on) better integrations with Django. But it will fade away. No way do I want to tie Django to HTMX, or any other frontend solution. Folks have been clamouring for this literally for years. But imagine if we’d tied Django to React. I’m pretty sure that might have killed it. Not being tied to particular solutions is a long-run strength.

Finally, if we start endorsing packages, it suddenly becomes political, and a target for spammers. Why is that package endorsed?, Why not this package too? That involves yet more curation work, and it’s always going to leave people upset, and feeling excluded. (If you include everything, it’s just noise.)

As Django has it now, the docs are a neutral zone. There’s value in that.

Official packages?

The last thought I want to cover is an idea that’s been talked about of making a number of (blessed) packages Offical in some sense.

That’s not necessarily well-defined. But some questions:

Do such come under the Django GitHub org?

What about a PyPI org, if those become a thing?

Do we then enforce Django’s API stability guarantees?

What effect does that have on development?

Would they be covered by the Security Policy, and the Django Security Team?

Does the Security Team have capacity for that? (Answer: it doesn’t)

And so on…

It’s not that we couldn’t do things here, but we come back again to the idea of capacity. Pulling things into Django sounds wonderful. But before we do that, we need to be clear on what the reality looks like afterward.

The reason I lean to the social solution of leveraging the existing ecosystem is that I think that looks like a much simpler set of problems entirely. Those seem to me problems we can address with the folks we have available.