An Annual Release Cycle for Django

A proposal for moving Django to an annual release cycle.

Django turned 20 this year. The version numbers roll on. Django’s time-based release schedule has been a huge success, and having spent forever on 1.x, we’re just about to roll over to version 6, can you believe.

I hear two complaints about our current versioning. The one is that it gives no information. Pop quiz: without looking it up, if you see a project on Django 2.2, can you say when that release was? How out of date it is? I can’t. No idea.

The other is that it looks like semantic versioning. We release a x.0 and folks are duly bemused about the lack of breaking changes.

Django 6.0 is (by design!) not a major change from the 5.2 LTS. Any x.0 release of Django could well have been the w.3 of the previous serious.

Perhaps the only time that wasn’t true was when we went from Django 1.11 to Django 2.0, dropping support for Python 2 in the process.

That stability is one of Django’s major selling points. That Django will stay with you pays-off massively over the software development lifecycle.

So, all the version numbering does is to mark Django’s LTS cycle. The x.2 is always the LTS, and then we jump to y.0 for the next release — but users outside the immediate Django community don’t grasp that, and in-fairness why should they?

Python’s Annual Release Cycle

With Python 3.9, Python itself moved to an annual release schedule (PEP 602). Like clockwork, each new Python version is released in the October each year. It has 2 years of full support, 3 more years of security fixes after that, before being End of Life (EOL).

The Python Developer’s Guide has an informative Status of Python versions page that explains it all.

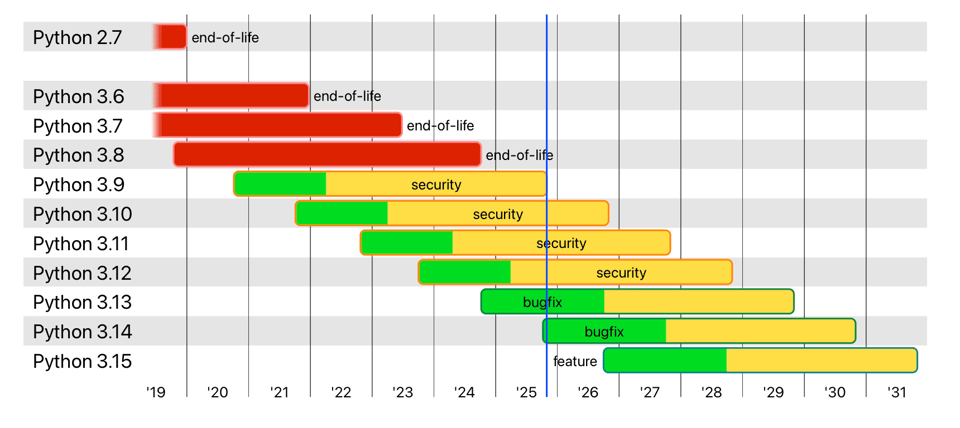

Here’s a screenshot of the headline graph there, showing the current and past Python versions as I write this, in October 2025:

Python 3.14 has just been released. Python 3.9 is just going EOL. Work has begun on Python 3.15, that will be released in October next year (2026).

Python’s new annual releases are a boon, but they place quite a burden on Django, given our current schedule — of a major release every 8 months, with every third release being an long-term support (LTS) release, with three full years of security updates.

Django 4.2 is now the old LTS. First released in April 2023, it doesn’t go EOL until April 2026, which another 6 months from now.

Django 4.2 supports Python versions 3.8, 3.9, 3.10, 3.11, and 3.12. That’s five full versions of Python. That’s a lot of CI.

More than that, though, Python 3.8 and (just now, this month) Python 3.9 are both EOL. By the time Django 4.2 expires, we’ll have been supporting an EOL Python there for 18 full months after it was officially dropped. With the idea of carrot and stick, I don’t think we do our users any favours here. Folks don’t update until they have to, and this extended support beyond the EOL date for a Python version just encourages (facilitates?) bad practice.

Third-party packages

The LTS cycle isn’t really helping package maintainers either though.

The idea was that maintainers would be able to support just a single major version of Django, 4.x or 5.x, and so on. As is normal for a x.0 release, the Django 6.0 release notes contain this advice for maintainers:

Following the release of Django 6.0, we suggest that third-party app authors drop support for all versions of Django prior to 5.2.

Django’s Stability and Deprecation Policies mean that if my package supports Django 5.2 without warnings, I’ll be able to support the 6.x series, without too much in the way of difficulty.

The issue is, though, that Django 4.2 still has several months to run at the point where Django 6.0 is released.

The reality is our users aren’t updating even then.

As I spoke about in my DjangoCon Europe talk last year, and wrote about here in my How we make decisions in Django writeup, at any given point in the release cycle, only between 50% and 70% of PyPI downloads for Django are of a supported version.

What we see is that that number drops off after each x.0 release. What’s happening is that the previous LTS is going end of life. Next April, during the 6.0 cycle, we’ll see the same thing, as Django 4.2 finally goes end of life and folks decide they’d finally better update to Django 5.2.

But that update doesn’t happen instantly. It takes about the length of the whole LTS cycle for the numbers to pick back up again as people slowly upgrade.

What this means for maintainers is that there’s significant pressure to maintain support for the older LTS, well beyond the point at which we’re officially meant to have dropped it.

The fairytale is that LTS-to-LTS updates are doable. In reality, we still say, it’s “usually easier to upgrade through each feature release incrementally”.

Firms want the LTS guarantees. They want to know they’re covered. The easiest time to upgrade is as the new release comes out, but if it’s not an LTS, I can’t. We create a situation where folks have no easy update path, and so they get stuck, well outside of the supported version window, no matter how generous this already is.

The situation is, then, we’re all stick: you have to update because you’re not getting security updates. The result is that large chunk of the user base (still) on an unsupported version. What the current release cycle is missing is any carrot. We need to be helping people to do that right thing.

To that end then, I want to propose that we move Django as well to an annual release cycle.

I’ll write this up as a DEP shortly, and will suggest we implement it from what would be Django 7.0, due for release in December ‘27 on the current system. For example here, I’ll use how it would apply to Django 6.0, which is just about to be released, as it’s easier to think about dates and Python versions as they are now, rather than projected two-years in the future.

The goal is to address some of those points above, give a clearer idea of Django’s release cadence and stability guarantees, and ultimately to make the number of users on a supported Django both higher, and more consistent.

Annual Releases for Django

The core idea is do one major version of Django each year, rather than one every eight months.

We shift the x.0 release from the December of each year to the January the following year — so delay it a month.

The prerelease phase would begin in the October prior to the release, after the corresponding Python version for that year is made final. (See below.)

We adopt a form of Calendar Versioning, where the first number is the year, and the second is the number of the release in the sequence.

For example, Django 2028.1 would be the first release of what was the 7.x series, 2028.2 would be the next release (likely the next month), and so on.1

Every release would receive one year of bug fixes — what we currently call mainstream support — and two further years of security updates — what we currently call extended support. They would end support at the final release (if there were one) in the December of the second year after their first release.

What this means is that every version would be an LTS.

We remove the barrier to firms updating to the next major.

Fellows Workload

Making every version an LTS obviously entails more work than only every third version being an LTS. How does that affect the Fellows?

The biggest task is major releases. By making those yearly, we reduce that by one-third. (Only two releases every two years, rather than three.)

In terms of on-going maintenance — keeping things running, backporting and so on — it’s the old LTS, so currently Django 4.2 that’s the difficult one. Normally it’s no problem, but when it is, it’s the old one. Pretty much always. Nothing on this proposal changes there.

We have an intermediate version that becomes the next old version, rather than going EOL (as say Django 5.1 will shortly) but that we have an intermediate versions remains the same.

We would always have three release versions in play, plus a possible pre-release, as we do now.

In short it’s a change, but not a big one. Fewer releases mean a small net gain I’d suspect. That likely dominates.

Supported Python Versions

If you look back at that Status of Python versions chart, you’ll see that only the latest two versions, currently Python 3.13 and Python 3.14, are marked as green. We’re meant to already be on those.

One policy then would be to support Green Only Pythons.

For Django 6.0, Django 2026, hypothetically, this would mean supporting Python 3.13 and 3.14 at launch. Then adding support for Python 3.15 next October, 2026, whilst still in mainstream support.

And then stopping. In October 2027, Django 2026 would be in extended support, and would not add support for Python 3.16. Django 2026 would end up supporting only three versions of Python, rather than five. That’s a massive saving in CI over its lifetime.

What’s more, Django 2026 would be EOL before any version of Python that it supported. Django 2026 would be end of life in December 2028. Python 3.13 is not EOL until October 2029 the following year. We’re finally inline with upstream expectations.

To give the example for Django 2028 — what would have been Django 7.0 — on the Green Only Pythons policy, it would release with support for Python 3.15 and 3.16, before gaining support for Python 3.17 in October 2028. That would be the limit of its Python support.

It’s possible the Green Only policy is the correct one. If I’m on Python 3.12, I can hang out on my existing version of Django until I’m ready to update. There’s lots of carrot there, and not too much stick: I have another whole year before it starts to look pressing.

One softening, though, would be, what we can call, a Plus Last Yellow approach. As well as the current green Pythons, we support also the last yellow Python. For Django 2026/6.0 this would mean also supporting Python 3.12 at launch. In terms of EOL, Python 3.12 is EOL in October 2028, which is just two-months before the EOL date for Django 2026, in December 2028. I think that’s probably acceptable. ”Hey, your Django and your Python versions are going EOL together — You’d better update now”.

A Plus Last Yellow approach would mean each Django version supporting four versions of Python, which isn’t quite the saving of Green Only, but it’s still significant.

Either of these approaches draws a nice balance. The only people it would exclude were those that wanted to be on an older Django but wanted the latest Python. That’s often been the source of pressure to add support for newer Pythons to existing Django LTS releases. (I remember Django 1.11 in particular being painful.) With every release an LTS there’s no need to do this. Just update your Django. There’s your carrot.

The Stability and Deprecation Policies

Django’s strength is its API stability. There isn’t anybody who’s used it for a while who hasn’t taken an old project and updated it to the latest Django with almost no problems.

We seriously underplay the business value of that stability. It’s at year two, three, …, five, and beyond that picking Django really pays off.

At the same time we want to allow Django to evolve and so there’s a Deprecation Policy to mark features as deprecated and remove them two features later.

We still want stability — that ability to tweak an old project and have it run is important — so things need to be “clearly superior” in order to be changed, but assuming that changed they will be.

In theory…

What’s happened in the past is that, even with the deprecation policy in place, some changes have been more difficult than others. Ones that come to my mind are adding required on_delete arguments to foreign keys, renaming all the force_text like utilities when dropping Python 2, and moving the routing helpers from django.conf to django.urls when introducing the modern path based routing. (No doubt, you’ll have your favourites.)

This has led to a kind of collective PTSD. Particularly where we know there’s a hard (unavoidable) breaking change there’s ever more resistance to adding the new feature — to making the change. In effect, the level for “clearly superior” creeps ever higher.

We end up with suggestions to extend the deprecation period, to do soft deprecations, to … — to in effect find any way of making the change without actually making it.

There's two ways that goes: either we make the change and leave cruft around for some undefined period (forever maybe) or we don’t, and Django’s pace slows, or feels like it does2. Neither of these outcomes are optimal.

So, it’s an adjunct to changing the release cycle per se, but as part of this, we should also make the excellent django-upgrade project part of the standard development process. If we want to make a breaking change, not only do we document it and provide a backwards compatible shim, and go through the deprecation process, but we also make sure there’s a django-upgrade fixer provided to make the vast majority of such changes entirely automatic. (All of the ones I mentioned could have been so addressed, I think.)

So doing, we unlock our ability to make even more adventurous changes without undermining our core value proposition.

Finally, since all releases are LTS releases, if any one change does mean it’s harder for me to update, I’ll have two whole more years in order to make that happen. It takes the pressure off. That’s more carrot: if you update each year, you buy yourself a bigger insurance window against an unexpected breaking change.

Django does the hard things

API Stability Guarantees are hard.

Long-Term Support Releases are hard.

A robust Security Policy is hard.

Yet Django does them all. We’re not some pre-1.0 maybe here tomorrow. We’re the proven solution you can rely on.

We should play to our strengths here.

An annual release cycle, with a predictable Python version support, with long-term support and security updates for every version is something that only Django can provide.

That’s why I recommend it to you.

An alternative here is to use the month number as the second part. That gives some extra information but after the first few releases, when the bug fixes slow down, we would expect gaps, for months when there’s no security release. If I’m on 28.15 and the next release is 28.18, did I miss something? Without checking I can’t say. If I’m on 28.11, and the next release is 28.12, I know I didn’t. The extra which month information isn’t so important, I think. ↩

So rarely is it fundamental what’s at stake, but the feeling of not being able to fix something is frustrating. ↩