11/5/25: On repacking your unpacked funeral clothes

an obituary I couldn’t bring myself to volunteer to write; a walk through Chicano history; thoughts about grief and the government; photos from reporting trips.

I’ve tried and failed to come up with different pithy titles for this. It’s hard to capture and describe.

“Funderemployment, grief, price-fixing and ICE abductions.”

“How to grieve when the world is on fire.”

“I love the city of Chicago, I really do, and everyone in it, all the time, every time.”

“Texting your local priest about last rites and putting Duolingo to the test.”

But I ended up settling on “On repacking your unpacked funeral clothes [and hugging friends who smell like tear gas].” It may as well also be “On unpacking your repacked funeral clothes [etc].”

What you can expect: an obituary I couldn’t bring myself to volunteer to write; a brief walk through Mexican and Chicano history; some thoughts about grief and the federal government; photos from some reporting trips.

It’s long. It took me a while to write. It’s got a throughline, though. This one won’t be too much about journalism. Not directly, anyway.

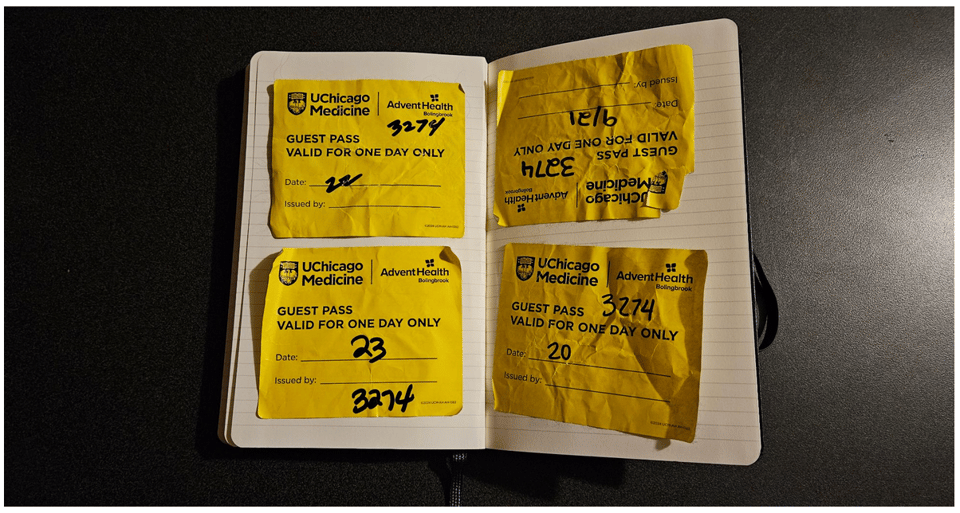

In my last note, I had said that I was writing things from a hospital waiting room. Happy to confirm that the wifi was strong, the coffee wasn’t terrible (though the lobby cafe was always closed at the worst times), and the food wasn’t bad, either. I wasn’t there for me — in what feels like a twisted mid-twenties rite of passage, I was there for my abuela.

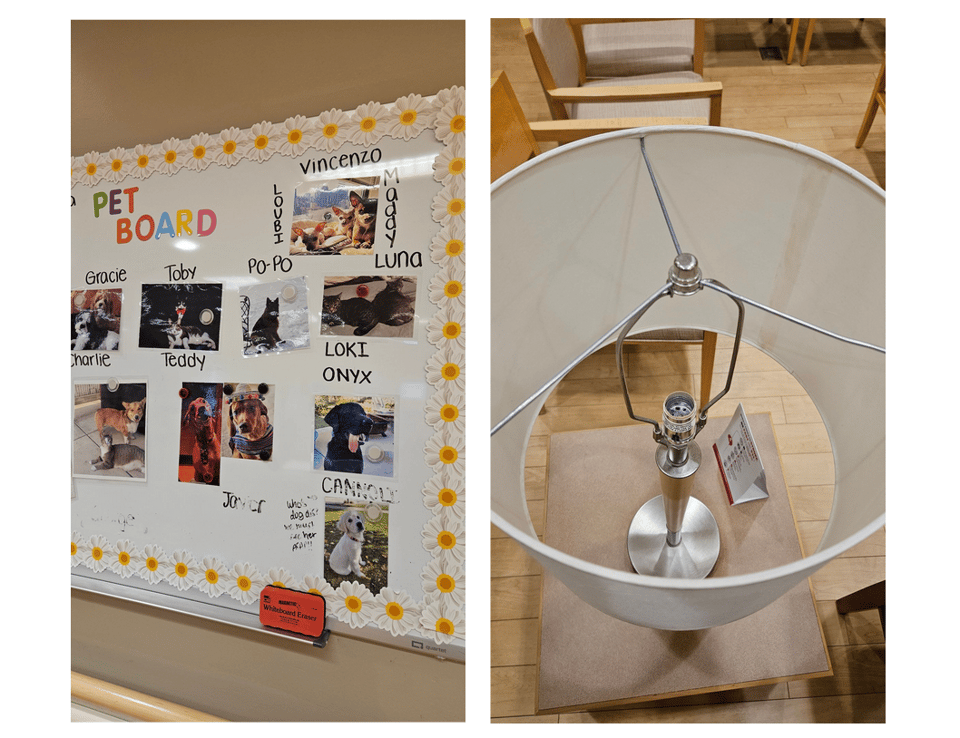

I arrived at the large, newer hospital in my hometown in the suburbs of Chicago on September 20. On September 28, I spent a final quiet day at my abuela’s bedside, surrounded by family and half-finished bags of chips and old Farmer’s Fridge jars. I filed job applications, worked on a story, and sent emails. I reconnected with family that we haven’t seen in a long time. I had popsicles and mocktails made by sweet CNAs. I watched as she transitioned from emergent to stable to hospice care.

I listened to her talk, a rare occurrence after watching her voice wobble then fade during her decade with Parkinson’s.

And I left that night knowing it would probably be the last time I’d see her alive. I was right.

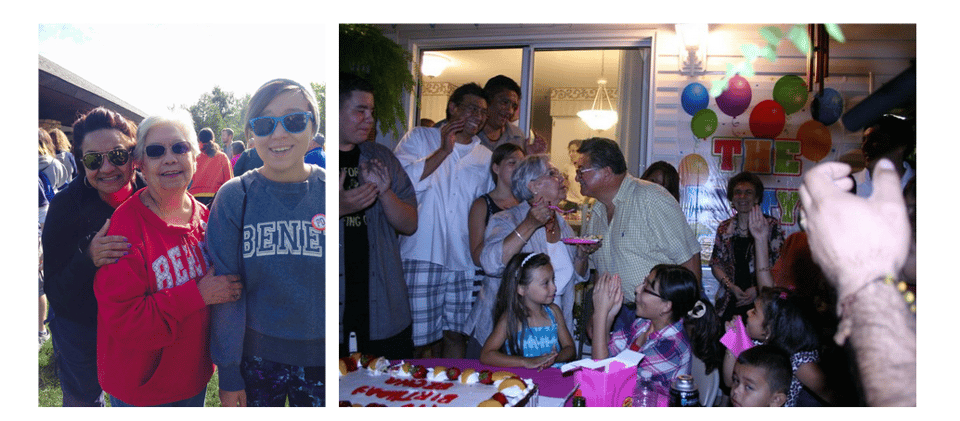

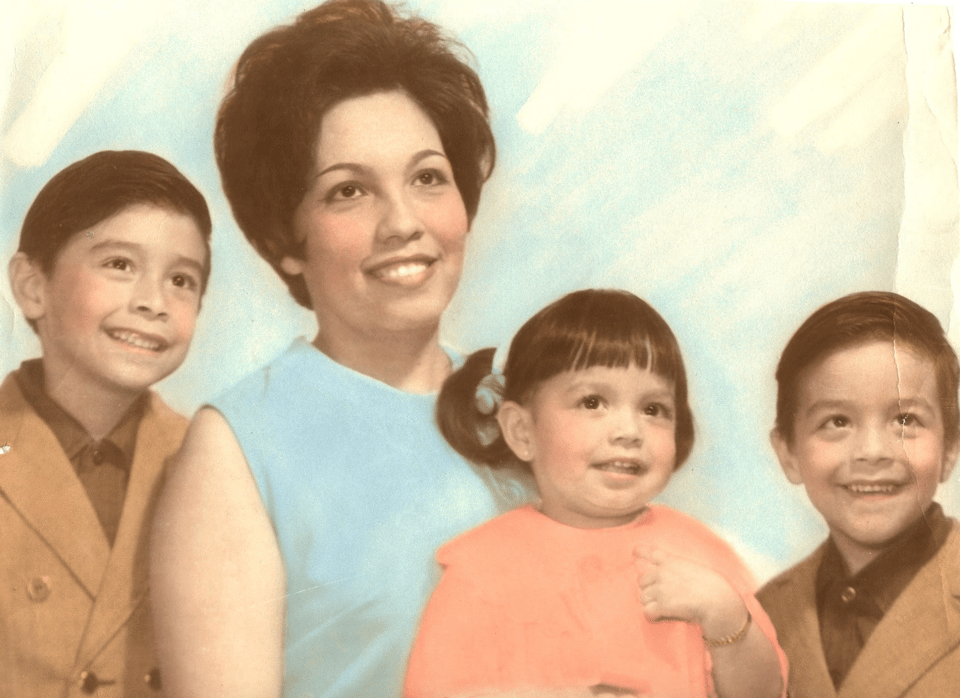

Maria Luisa Rodriguez Infante was an incredibly strong-willed, diligent, hard-working woman who cared about a few things intensely: her family, first and foremost, then church, then the Chicago Cubs.

Conchas and pan dulce, which she’d always have with her milky and sweet coffee. Dolly Parton, Johnny Cash, Hank Williams. La Rosa de Guadalupe. Crocheting doilies for the parish. Going on five-mile walks on the paved trail ComEd put in under the high tension lines by the house. Anthony Rizzo. Sunday night phone calls, every week, even when she couldn’t hold the phone from tremors and muscle atrophy. Altering every piece of clothing she owned so they fit just right. Hitting up Subway, then when that closed, Jimmy Johns (sorry, “Yimmy Yohns”), so often that they knew her order when the car pulled up. Going shopping every week after church, to the same department store. (Dragging her grandkids to shop with her at said department store.)

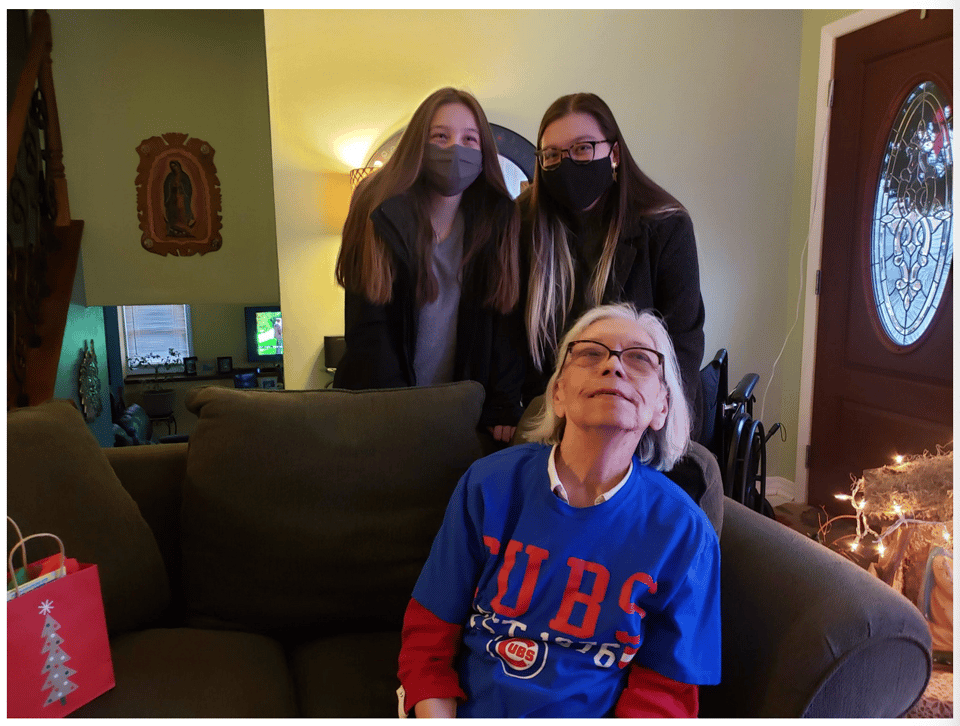

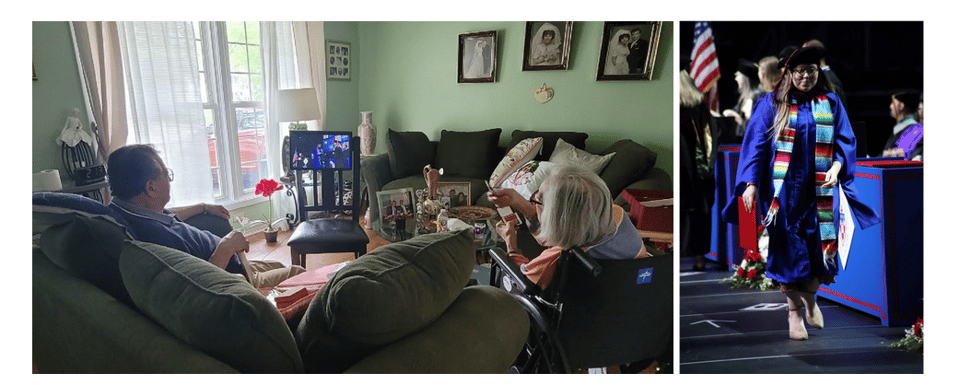

I owe everything to her. She taught me Spanish, made sure I had a ride and a place to go after school every day until college, watched my sister and I grow up, take our first steps, our first tumbles. There wasn’t a single band recital, choir concert, volleyball game, softball tournament, rock climbing competition or school talent show that she missed. When I walked across the stage to receive my Master’s, with a serape stole around my neck, she watched from her wheelchair in their living room.

So I’ve been a bit out of commission for a while. I’ve been slow to respond to nearly everything. I’ve been spewing apologies to everyone I know. In truth, I’ve had a hell of a month. All of this has come at a time of massive change. I’ve been handling it okay.

In one, single fucking fever dream of a week, I:

watched a parental figure die, (Tuesday)

received a diagnosis for an autoimmune disease that will impact my mobility for the rest of my life, (Monday)

fought like ten insurance companies for the medication for said diagnosis, (M-F)

stood in and spoke at my best friend’s wedding, (Wednesday, Thursday)

had my last official day at the Times, (Friday)

attended the funeral for said parental figure, (Saturday)

and then went home. I had a dog very excited to be back in Chicago, a fridge full of rotting groceries, a greenhouse with limp and dying plants, and a suitcase with haphazardly-packed black clothes that I left untouched for a while.

I kept mostly to myself. I lived on the couch. I filed job applications. I worked on a story. I sent emails. I had job interviews. I got rejected after job interviews. I ordered a gluttonous amount of takeout. I walked the dog.

Grief is strange. And in Chicago, I’ve felt layers and layers of it.

While my abuela was in the hospital, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers, who were prowling Chicago and the suburbs as a part of Operation Midway Blitz, were staking out my hometown. They posted up at the grocery stores where my abuelo will spend an afternoon figuring out the lowest avocado prices. They hid around the corner from the library and middle school during pick-up and drop-off.

While we had family flying in to visit my abuela and spend time with her in her last minutes, we had to warn them of the situation they might encounter, downloading Life360 onto the phones of elderly family members in order to make sure we knew where they were. While my abuela declined, and it was painfully clear we’d all be attending a funeral soon, I’d scan social media for possible sightings of ICE as family went out to go to Kohl’s or Macy’s and get a suit or dress.

While my grieving grandfather was driving home from the hospital every night to the house that he and his wife moved into after immigrating to Chicago from Mexico in the 1970s, the house that raised my dad, uncle, aunt, then my cousin, sister and I, ICE was lurking around the corner in their neighborhood.

My sister and I, with deep pits of anxiety in our guts, would follow our abuelo on the five minute drive home. It wasn’t even a question in our minds, just something that we knew we’d do. Just in case, we’d say to each other after, eyes scanning every car, trying to peer past tints in order to see who was inside. We might as well. Just in case.

Since my abuela died, ICE has continued to execute Operation Midway Blitz in my hometown. They’re frequently spotted on my grandparents’ block, on the same street where I learned to ride a bike, skinned knees, chased after cousins and cousins’ cousins, where I grew up. They’ve been inextricable from each other, the militarized occupation of my community and my abuela’s death.

Facebook has been a daily habit of mine as of late; I’ve been checking group after group, which keep getting axed by Meta for supposedly doxxing federal agents, to see blurry photos and videos of my neighbors and old classmates’ parents and community members getting arrested. Then there are pretty desperate, but simple, heart-wrenching posts: “Alguien sabe cómo anda todo por tonys walmart y fiesta market necesito ir por mandado.”

Does anyone know how things are going? I need to run errands.

Nonstop. All day. Cars and trucks abandoned in the parking lots where people are arrested. People afraid to leave their houses in a place they’ve lived for decades, because federal officers are pulling over pretty exclusively Latinos at random, pulling them out of cars, detaining them in front of their kids, in front of their churches, in front of their grocery stores and schools and friends.

I get texts, every so often, from ICIRR’s “Eyes On ICE” program, letting me know just how close they were that morning. I rack my brain’s mental map of my hometown, trying to figure out where the cross streets are.

The grocery store? Is that by the church? The apartment complex by the Walmart? No, the other one. By the Culvers? By Menards? By the elementary school? By the library. They’re by the post office. The senior center. Now they’re spotted at this restaurant. Did you know they’re staying at the Holiday Inn Express? Did you know they’re staging in the parking lot of the police station? By the ice rink?

I’m reminded of two specific, disturbing periods of history that I only learned about in the past few years. Both evoke a sense of bile-rising-in-my-throat kind of disgust, but also make me incredibly proud to be Chicana.

I’ll work backward and start with Operation Wetback.

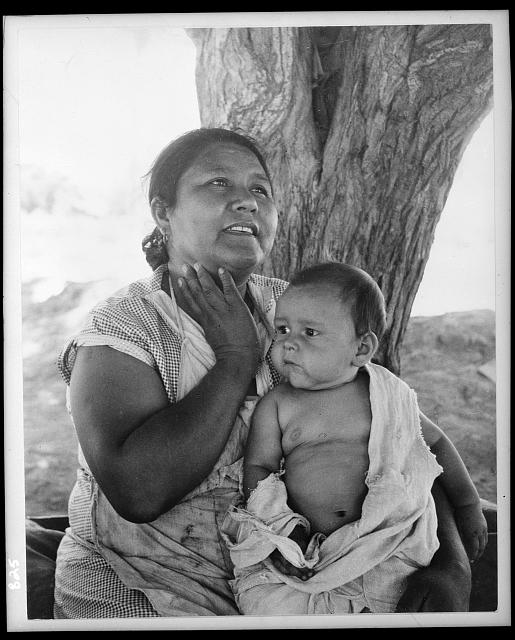

While the United States battled the Axis powers on the global stage, Mexicans, in part through the Bracero Program, but also more specialized work programs, were able to fill the gaps left by those who left to fight in the war. The Bracero Program paid Mexicans a sub-minimum wage in exchange for easy (“easy”) access across the border for work.

Joseph May Swing, the commissioner of the INS, or the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the precursor to what we now know as USCIS, wanted them gone.

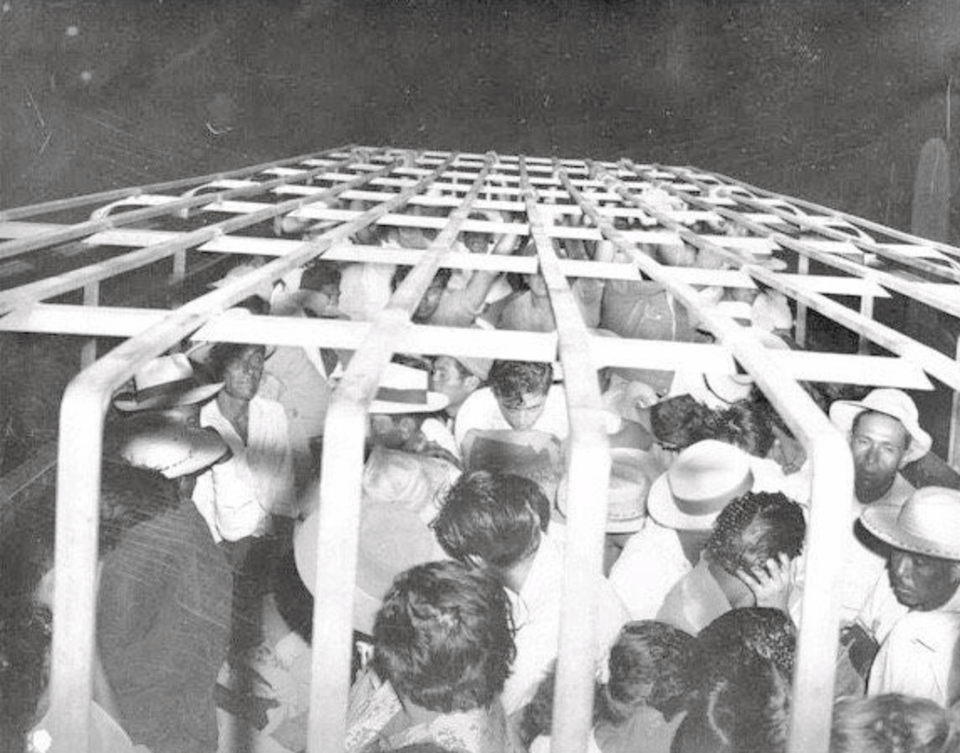

It led to one of the largest mass deportation campaigns in history, one that spanned a decade of postwar America: Operation Wetback. Hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Americans of Mexican descent were forcibly removed from the United States by truck, train, boat and plane.

But before Operation Wetback, only by a generation, was a government-supported mass deportation program: Mexican Repatriation. In an attempt to find a scapegoat for the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover blamed Mexicans for taking jobs, being of poor character, tanking the economy, etc, etc, etc. And he wanted them gone.

It led to the forcible removal, and coerced self-deportations, of up to an estimated two million people of Mexican descent. Approximately ½ to ⅔ of those who left during that time, either by force or out of fear, were U.S. citizens. A significant amount of the people who were forcibly removed from the United States were children and families.

In 2005, legal scholar Kevin Johnson argued that the forced repatriation of Mexican immigrants and Mexican-American citizens met the modern definitions of ethnic cleansing:

“This is not to suggest that a genocide of persons of Mexican ancestry occurred in the 1930s. Rather, it was only a forced removal of a racial minority from this country. Consequently, the Mexican community of the United States experienced human tragedy other than death. Specifically, the mass deportation campaign of the 1930s destroyed lives. Families were torn apart. The Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant communities, as a whole, were terrified and the impacts were profound and enduring.”

I first(!) learned about Repatriation in 2023, when my mom and I pulled off the interstate to visit the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Memorial, in West Branch, Iowa. We were teary-eyed after dropping my sister off for college, and decided why not, let’s go to the roadside museum. (I needed to add a stamp to my collection, after all, and this was an NPS-adminstered site.)

I ducked in with the intention to get a stamp, grab a pamphlet, stretch my legs, and get out. I caught the glimpse of a placard. (Always read the plaque.)

I was utterly horrified. I couldn’t believe that this was the first time I was learning about a significant part of my community’s history — not just Mexican history, but American history. Chicano history. How could I — the person who is obsessed with history, with unpacking narratives — not have known about this?

How could I not have been taught about this?

I remember we drove around the small scenic path in West Branch, toward a small hill with his grave and the presidential library itself. My mom and I were silent. I couldn’t help but think about how the president buried only ten feet away probably would have resented the fact that I was here. (Here, off I-80 in West Branch, Iowa? Here, in the United States? Unclear.)

All of this has occupied a ridiculous amount of my brainspace. It’s impossible to ignore. It’s negligent to ignore. Any time I visit home, which has been a lot, lately, I have my eyes scanning every SUV. I take routes to pass by areas that typically have lots of ICE activity. I detour to do loops around my grandparents’ block, feeling a familiar pang of grief when I pass their house.

I walked to a coffeeshop today, where I’m writing this now, and heard a whistle down the block. It ended up being a kid, playing with a little Dracula-mouth-shaped whistle, and it filled me with enough cortisol to last me a week. As I wrestle with grief pretty much every second of every day, it makes me wonder how our community will cope with the fallout, once they — ICE, and the people they took — are gone.

I should probably mention the other parts of the title.

Price fixing and insurance: one of the medications that can supposedly reverse the progression (aka stop my body from attacking itself and trying to fuse my bones together) of my Fun New Diagnosis is a biologic, which is a sort of marvel of modern medicine that Big Pharma™ likes to charge a bazillion dollars for in the attempt to make sure they can make bank. That’s not hyperbole, either — this is something that the Times has actually written about, including the great lengths that folks have gone to get said medication, like a company flying a woman out to Jamaica in order to receive the meds at a cheaper price.

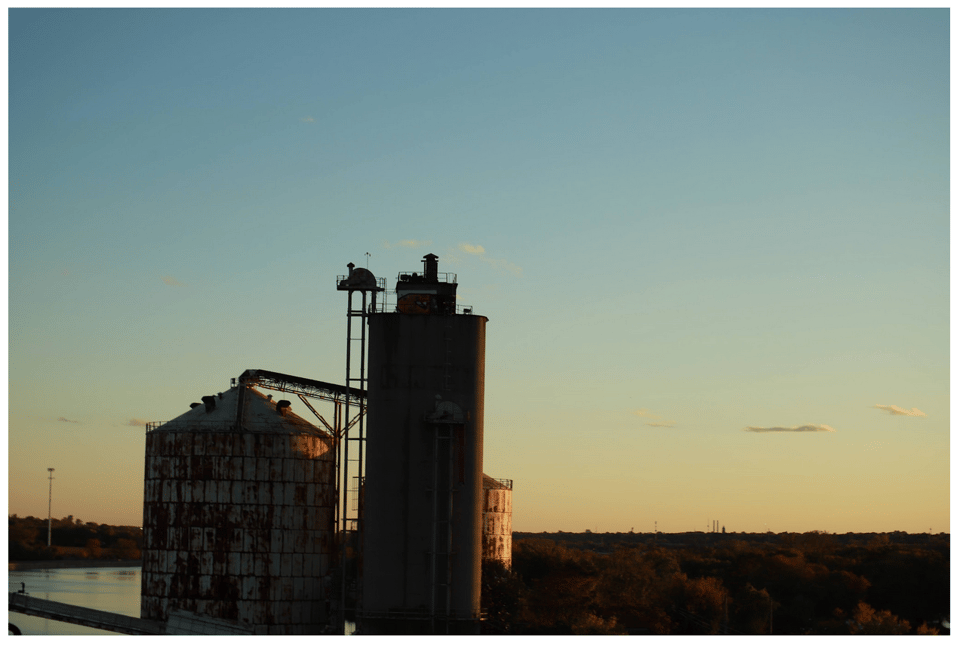

Un/re/unpacking funeral clothes: I’ll need to talk more about this in detail probably at a different time. I spent a good amount of time a couple weeks ago in the field continuing the reporting that I’ve been doing with the Times. It involved memorials and vigils, was positively soul-crushing and led to lots of time being pulled over, staring at big combines in the full throes of harvest season, watching them kick up dust and blasting music loudly. One of the worst things about reporting on complex issues where people are harmed is learning about more people being harmed. An absolute stab in the stomach, with the knife twisting as I realized I had to repack the black clothes I had just unpacked.

The tear gas: there’s nothing quite like tagging along to a local KYR training with your neighbors, scoping out the area, seeing how things are going, and running into reporter friends and colleagues. I went in for a hug at one point with one. “Sorry if I smell like tear gas,” this reporter said. “I just got back from East Side. I went home and showered and changed, but it’s still lingering in my hair.”

To wrap this up, though I doubt this will be the last of any of this: this poem by José Olivarez has been making the rounds this week amongst Chicago. I’d say that it’s remarkably accurate to the tenor of the city that I’ve felt, or at least in my loudly and proudly Latino neighborhood. One that I come back to time and time again is this one, poem where no one is deported, from 2021.

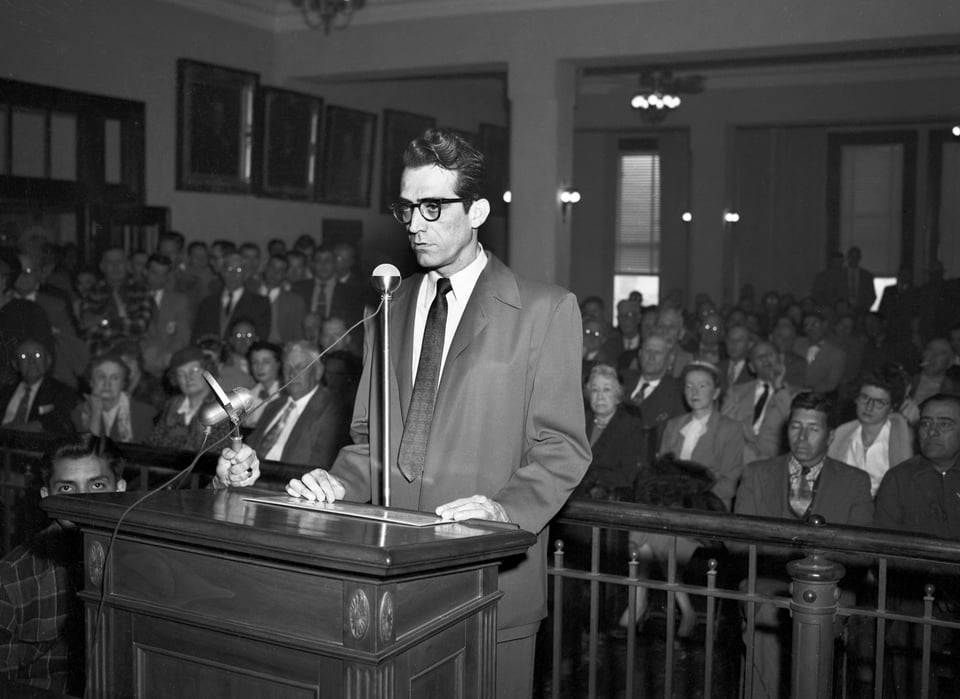

The thing that has the most staying power with me right now, though, is a speech from iconic Chicano lawyer Gustavo “Gus” Garcia.

Garcia, who worked with braceros, LULAC and AGIF, and who argued as part of an all-Mexican-American legal team in front of the Supreme Court for Mexican-American rights in the 1950s, gave a speech to UNESCO in January 1952 about the segregation of Mexican-American students in U.S. schools.

The height of Operation Wetback, in the shadow of Repatriation, sailing into the Civil Rights Era.

It ends with a hell of a kicker, one that I have printed out and taped to the side of my fridge beside the coffeemaker:

I believe that we need to cultivate the virtues of charity, and I mean charity without contempt; of understanding, and I mean understanding without superiority; of sympathy, and I mean sympathy without paternalism. Let us remember that the time passed long ago when we could consider as inferior, peoples of other nations simply because they had other cultures or customs or different spiritual values. It is high time that we realized that we are not really better—— that we are merely better off.

Personally, in spite of all this, I look to the future with boundless optimism. I feel that if civilization was able to endure the Dark Ages, we certainly should be able to overcome any political privateers who are now preying on our fears, our gullibility and prejudices. I feel that regardless of iron curtains, human beings in Murmansk and in Cairo and in Manila and in Busan and in Belfast and in Des Moines and in Laredo are seeking essentially the same thing: a better way of life for themselves, if possible, but definitely a better way of life for their offspring and succeeding generations.

People are tired of war and, except for avaricious few at the top, they are also tired of greed. God grant that all these hundreds of million of souls — these simple and humble little people — be allowed to find what they seek. Let us hope that our fantastic technology, already hundreds of years ahead of our spiritual world, will not destroy our civilization and plunge this earth into chaos and perhaps eternal darkness.

So. I’m still filing job applications. I’m still working on stories. I’m still writing emails. I’m sure the next iteration of this will be more focused on journalism, or craft, or GIS, or whatever. I’m not 100% there yet. But I’ll get there.

A lot of the Facebook posts I’ve seen recently have signed off the same way. I’ll sign this one off like that, too: Cuidado y cuídense.

You just read issue #4 of junk drawer. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.