Too Real, Seth Rogen! My Thoughts on The Studio

Hi! First of all, a quick update… I am still working on All the Seeds in the Ground, the sequel to All the Birds in the Sky. It’s starting to look like folks who pre-order my upcoming novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster will get more than the 10,000 word preview I already promised — possibly a lot more. I’ll keep you posted. As a reminder, you also get deleted scenes from All the Birds in the Sky and an alternate ending. That’s a PDF you will receive in August if you share your receipt with me at this Google form or email it to me at limadcopies@gmail.com — details here. I really appreciate your support, and it’s also really helpful to get a sense of how many people are interested in that sequel. Honestly, it makes such a huge difference in so many ways. Thanks so much to everyone who’s already sent a receipt in! With that out of the way…

Why Seth Rogen’s The Studio Made Me Think About Comedy and Reality

I decided to check out Seth Rogen's new show, The Studio, because I still had an AppleTV+ subscription after watching season two of Severance, and I'm going to keep it long enough to watch Murderbot.

I enjoyed the first couple episodes of The Studio, in which Rogen plays the head of a major movie studio who struggles to balance commercial success with artistic ambition. It's fun and stylish, and every episode is suffused with a deep love of movies. The supporting cast, especially Ike Barinholtz, Kathryn Hahn, and Catherine O’Hara from Schitt's Creek, are firing on all cylinders.

Still, the first two episodes didn't entirely land for me, especially the first one. And this made me think about a topic that's close to my heart: how to be funny while also respecting your characters.

Spoilers for the first few episodes of The Studio ahead…

The way I see it, the issues with the pilot episode of The Studio fall into two buckets:

1) The show sets up an absurdist situation that ultimately doesn't ring true and makes Rogen's character appear wildly delusional.

2) The show is very committed to having real Hollywood legends play themselves, including Martin Scorsese and Charlize Theron, but it won't make fun of them. (At least not in those two episodes — see below.)

So… in the first episode, Rogen's character, Matty, gets the job of studio head that he has wanted for a long time. He immediately does a huge interview in which he says that he's going to focus on making great films rather than IP slop. But then it turns out that his boss wants him to make a movie based on the Kool-Aid Man — or at least the Kool-Aid brand — or he’ll lose his new job.

By coincidence, Matty has a meeting with Martin Scorsese, who has a movie pitch about the Jonestown massacre1 which, of course, includes suicide by Kool-Aid. Rogan's character decides that he can fulfill his mandate to make a Kool-Aid movie by green-lighting Scorsese’s film and titling it Kool-Aid.

This is obviously a super heightened premise, which is intentionally absurd. But it does make Rogen's character seem so incompetent that it's obvious he should never have gotten that job. Even a five-year-old knows that major studios in 2025 need to do a certain number of cruddy IP films in order to stay afloat. This is not because they are evil, but because moviegoers steadfastly refuse to show up for original films, except once in a blue moon. (Here’s where I once again pimp my favorite podcast right now, The Box Office Podcast, in which Scott Mendelson, Lisa Laman and Jeremy Furster regularly expound on how difficult it is to launch any movie that's not a brand name.)

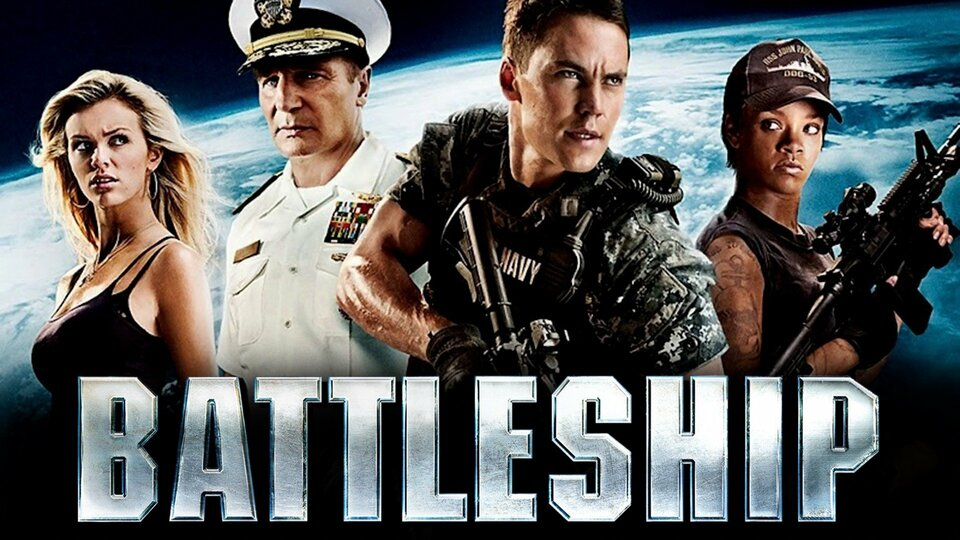

And of course, not all IP is valuable IP: see Stretch Armstrong. It is highly likely a Kool-Aid movie would be an expensive disaster, much like the Battleship movie from a decade and change ago.

We're supposed to believe that Rogen's character has worked for this studio for twenty years, but he has never learned this basic fact. He has somehow completely remained oblivious to the fact that four-quadrant IP films have been paying his salary and keeping his studio from going bankrupt this entire time. You make the Kool-Aid movie to subsidize the Martin Scorsese movie — everybody knows this.

Yes, I realize I am fact checking a comedy. And that is a ludicrously wrong headed thing to do.

Still, none of the jokes about turning Scorsese’s Oscar-bait movie into a Kool-Aid film worked for me, because I never believed in the situation. Honestly, it felt like a two minute comedy sketch stretched out to a half-hour episode. In order to make it work as an entire episode of TV, the premise would have needed legs that the lack of plausibility hacked off with chainsaw like efficiency.

Which brings me to the second point: the celebrity cameos. At this point, Hollywood a-listers playing themselves in various things has become a time-honored trope. To the point where it’s kind of overdone, and I would be happy never to see it again. Back in the day, when James Van Der Beek played a parody of himself in Don’t Trust the B— in Apartment 23, it was kind of charming. The Player, which The Studio references explicitly via the name of Matty’s boss, was great back in 1992. Etc. etc. Still, I feel like if you have to have celebrities play themselves, it works best if they play exaggerated, over the top, caricatures of themselves as egomaniacal monsters. It doesn't work nearly as well when they are simply playing a grounded version of their usual selves.

And when it comes to Scorsese in the first episode, plus Sarah Polley in the second, the studio seems to bend over backwards to treat these people with kid gloves. They aren’t allowed to be the butt of the joke, or even to be shown as flawed human beings. They must be sacred and inviolable — which means that Seth Rogen has to be consistently the butt of every joke, which gets exhausting. This setup makes it incredibly hard to invest in Rogen’s character.

I came away from that first episode thinking it would have worked way better if the director in question had been named Fartin Floorbaby, and had been played by one of the army of white baby boomers who specialize playing obnoxious jackasses.

I generally enjoy Seth Rogen’s comedy, which is why I checked out the studio in the first place. And I do think the show plays to his strengths in many ways: he is playing a hapless schmuck, but also a guy who genuinely loves movies and has a deep knowledge of film history. His character sincerely, passionately wants to create great art and just cannot get out of his own way. Which makes it all the more frustrating when Rogen's character, who is the protagonist and the person we identify with most, is the only one who's allowed to be the butt of the joke in those opening episodes because we couldn't have Fartin Floorbaby.

Proving my point somewhat, the third episode, in which Ron Howard is willing to play himself as a self-indulgent sadistic freak, is one of the funniest and most engaging things I've seen in freaking ages. All of a sudden, Rogen's neurotic studio head someone ridiculous to play off. It’s like night and day — the comedy works so much better in episode three than in the first two.

To be clear, I'm legit enjoying this show and will definitely watch the rest of the first season soon.

The question of how to be funny without undermining my characters to the point where the audience loses interest in them or stops giving a crap about them is something that I’ve struggled with for my entire career. I’m just gonna quote from what I told Psychopomp Magazine a couple years ago:

Sometime in 2011 I did the thing that you’re not supposed to do, and read Goodreads reviews of some of my short fiction output. I came across someone on Goodreads who said of one of my stories, “Once again, Anders is using humor and snark as a substitute for fully-developed characters.” And even though I knew that feedback wasn’t intended for me—it’s important to recognize that reviews are not aimed at the author or creator—it still hit home.

That was a turning point for me. Earlier in my writing career, I used to throw my characters under the bus for the sake of a joke all the time — either by having saying having them say things that were funny but slightly out of character, or by having them become the butt of the joke just such a huge extent that they stop being legible to the audience. It’s the reason why I tried so hard to balance character and humor in All the Birds in the Sky, which I really think made the jokes funnier.

When you stop believing in the characters in a long-form narrative (not a comedy sketch), it’s easy to check out and the jokes stop landing — unless you’re really just going full cartoon. I kind of talked about this last week in my piece about believable characters in unbelievable situations.

I strongly believe that it is possible for a joke to come at a character's expense without us losing sympathy for or faith in that character — in fact, sometimes we sympathize the most with the characters we laugh hardest at.

It's a fine line, because I do not believe that we should only laugh with characters and not laugh at them. I love laughing at fictional characters! Including the protagonists! Laughing at fictional people is often a huge safety valve that compensates for all the real-life people that we probably shouldn’t laugh at, especially to their faces.

I've been fascinated with the nature of the comic hero for a long time. That's one reason I was always interested in Henry Fielding, which led me to the focus on 18th century novels in my new book Lessons in Magic and Disaster. Way back in Rock Manning Goes for Broke, Rock muses:

Think about it! Harold Lloyd is the same guy in every one of his movies — a small-town innocent, maybe a little egg-headed but not street smart, with his heart on his sleeve but also full of loopy ambitions… The comic hero has to be lovable or relatable, or at least there has to be a moment of connection with the audience in between all the falling gargoyles.

So I think it's mostly a matter of suspension of disbelief, honestly. I love chaotic heroes who make gonzo decisions, but I just need to believe in the reality of their worldview. And I need to have a clear sense of where and how the external world is pressing up against their inner life, and how the two come into conflict.

Music I Love Right Now:

Irma Thomas is a giant of New Orleans soul, who worked a lot with Allen Toussaint back in the day. The “Queen of New Orleans Soul” has been putting out hit records since 1959, and she’s still going strong. And now, she’s teamed up with New Orleans funk band Galactic to release a new record called Audience With the Queen, and… holy shit. Pretty much every song on this record is an absolute banger, though the opening track is a bit of a slow burn at first. It’s tight as fuck. Stanton Moore is bringing his A-game on drums with a lot of snap and shuffle, and Robert Mercurio playing a laid-back but bouncy bass. You could easily convince me this was a lost Sea-Saint Studios classic from 1973, except that the lyrics feel very now, including references to Black Lives Matter. And the stripped-down, jazzy Galactic sound is fully represented. Irma Thomas’ voice is just as urgent and pressing as ever. I am obsessed with this record, and it’s what I needed right now. Please check it out!

An earlier version of this piece mistakenly said the Manson Family. Sorry about that! I regret the error. ↩