strange fits of passion

If you were educated in an English-speaking high school or the equivalent, it’s possible that at some point you read Wordsworth’s “Lucy” poems, a maudlin bit of mourning for an idealized lost love that begins, not by mourning at all, but by imagining Lucy’s death. The first poem sees the speaker clip-clopping along on his horse thinking about his girl, and then, bam, the moon drops out of a cloud and the bottom drops out of the poem:

'O mercy!' to myself I cried, /'If Lucy should be dead!'

— And the poem abruptly ends.

Because I was a giant anxious nerd (and perhaps because my dear English teacher took just a bit too much glee in this ending), I obsessed over these two lines. What did it mean that the speaker could so easily and immediately switch from daydreaming about his beloved to wishing her dead? Forever after, every time I had an intrusive thought about harm befalling someone close to me, I would think:

If Lucy should be dead!

In October, I bought a house in Tennessee (and round it was upon a hill — I just remember bits and drabs of poetry and they follow me around intruding into my brain forever) and then the next three months of my life were spent dealing with the ups and downs and stress and more stress of mortgages and insurance and cross-country moving and paperwork and airports and movers and cleaning and contractors and more contractors and on and on, and I basically gave myself permission not to do a newsletter update until I was properly settled in my shiny new house. It is now nearly April and I am still not properly settled in my shiny new house, but more pertinent is that I still haven’t fully processed everything of which I’m about to write.

While I was deep in the middle of house-buying, I watched Yibo spend two days racing for the Uno racing team in the GT Sprint Challenge in Zhuhai. The first day, he and his racing partner Adderly Fong placed second; the second day, after a dramatic car crash between the two lead cars left an opening for Yibo (who had to start several cars back), he and Adderly placed first overall.

I watched both races, livestreamed by a couple of fun excited Italian guys who courteously took time to explain some things in English for their sudden influx of international streamers. Both days, I genuinely kind of felt like I was hallucinating. Like I’d entered some kind of bubble that would burst any minute and send me back to reality, where overworked actors with limited training don’t just get into million-dollar race cars and zoom zoom like they’ve done it their entire lives.

Prior to the race, in every single training session he’d had, Yibo had spun out and wrecked — sometimes due to the rain, several times due to the cars breaking down, and sometimes because that’s just what happens when you’re learning. I had never once seen him complete the course. I didn’t think he’d be able to do it. I was absolutely terrified that we’d see him spin out and that he’d do it on a racetrack full of other drivers, who might not be able to swerve out of the way quickly enough to avoid disaster.

It’s not like 2024 went easy on Yibo. His pivot to wilderness exploration left bruises and cuts on his hands, gave him altitude sickness, nearly gave him hypothermia, and involved holding his breath for a frankly terrifying amount of time underwater. If some people dance with danger, Yibo was sashaying right up and doing the cha-cha.

It wasn’t particularly unreasonable to be worried, to feel that with all of this adrenalin chasing, Yibo might be overdoing it, burning the candle at both ends, something —all on top of racing being an unpredictable, dangerous sport!

But then the races happened, and you watched him race and it was just like watching a duckling enter the water for the first time — no hesitation, no fear, nothing but grace and the sense that he is naturally at home in this space. I had just written days before this race about how quickly and deeply Yibo learns new skills, and I have spent the last five years watching him amaze and astonish us all with his ability to quickly pick things up — but to see him race that sprint at Zhuhai was a whole new level of astonishment.

At one point, while watching him, I genuinely found myself wondering if maybe race-car driving just isn’t that hard — if maybe the idea that it’s really difficult and requires all sorts of skill and training is just something that’s been fed to us over the years by Big Racing, when really all you need is a smart little brain and millions of dollars to spend on cars and good coaches and—

—But then, on the second day, that crash happened, with not one but two drivers spinning out right in front of him. While I was having a slight heart attack about it, Yibo just calmly went around the wreck and kept going like it was nothing at all. Immediately, the racing commentators began talking about how impressive that was, for a driver in his debut race to handle such a moment so calmly. We’d previously seen Yibo race in a sport where the other racers disrespected him and his ability, but in that moment, Yibo put paid to any lingering doubts about his ability. He could handle himself on the track.

I spent the rest of October, and then the rest of November and December, trying to wrap my head around Yibo’s win and how I felt about it — how to hold all the joy and pride he clearly felt, achieving such a longheld goal alongside people who respected him, alongside the inevitable fear and worry and no don’t please don’t that I get every time he steps into another racecar or scales another mountain or rappels down another sheer embankment or dives without an oxygen tank or, or, or, or.

And then came New Year’s Eve.

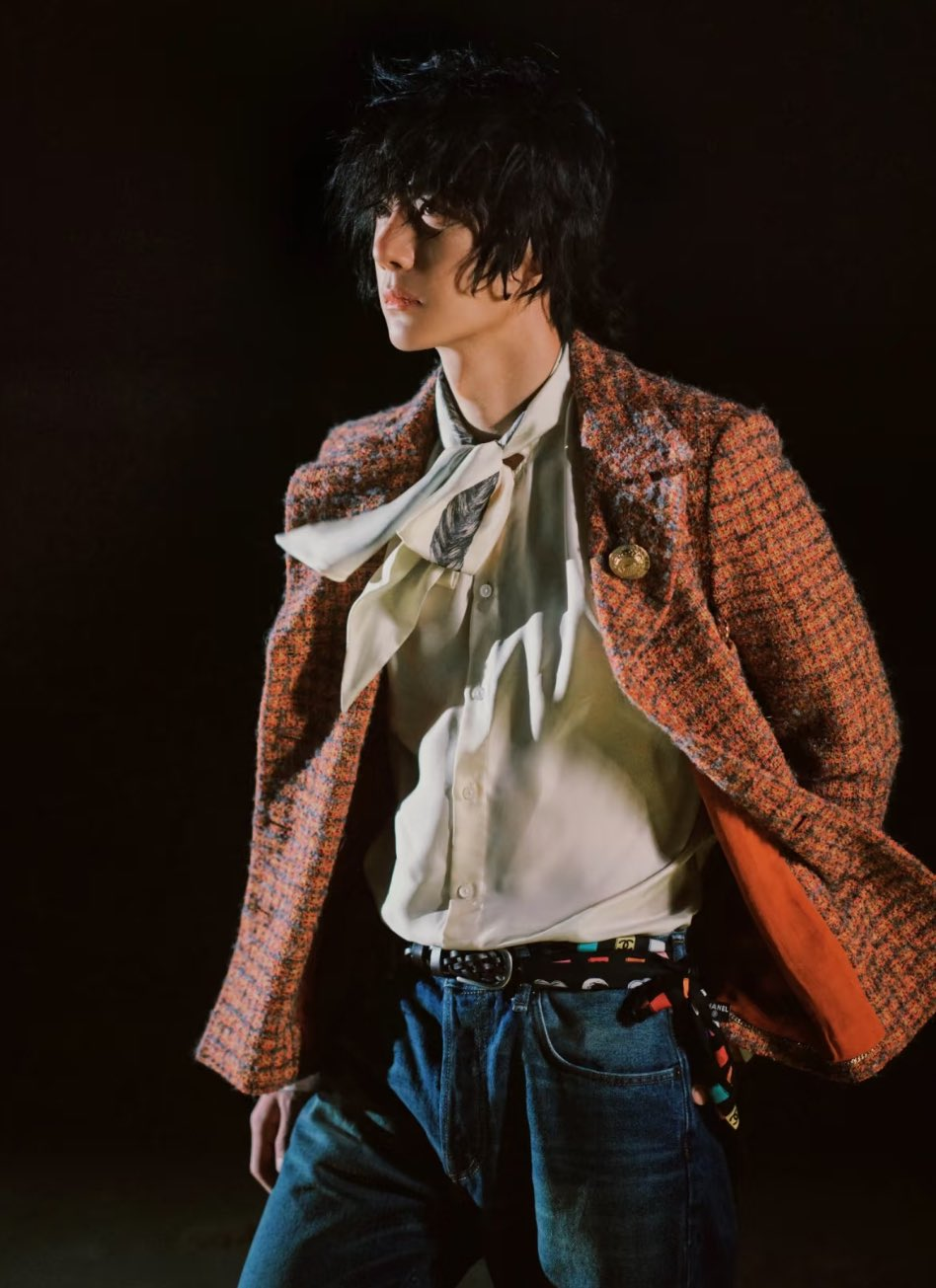

The thing is that New Year’s Eve was supposed to be safe. It was well-known territory, Yibo performing for his home network in Hunan, among friends, among the Mango TV crew that always takes care of him, loves him, crowns him king of the evening, every year. He wasn’t even dancing. He looked amazing, swathed in his chef’s kiss Bob Dylan cosplay that may be my favorite outfit he’s ever worn.

He was in his element. He was home. He was… dangling 160 feet in the air with a broken carabiner, and nothing, absolutely nothing, to prevent him from falling to his death except his own mid-air precautions, the still-functioning carabiner on his left side, and the hope that maybe the god of Danger, having cha-cha’d with Yibo all year long, had grown fond enough of him to let him lead.

Liu Yongbang, who’s been one of Yibo’s climbing instructors since Exploring the Unknown and seems to have gotten pretty close with him, made a Weibo post that seemed to imply pretty strongly that Yibo knew there was an issue during the performance and may have altered his moves accordingly. We’ve had conflicting reports that staff might have known ahead of time there was an issue. I have written here before about how much faith Yibo places in his tools, and how he’s able to take the risks he takes with his own safety and his own health because he has such trust in the tools and the people around him. It only took one careless stage worker casually leaving Yibo’s harness unhooked right before he floated away on it to shatter that entire system.

And look, there’s so much that needs to be said about the poor safety standards and hazardous workplace conditions in Chinese entertainment, still, six years after the death of Godfrey Gao. Then there’s the pressure placed on the actors and idols themselves, to push themselves to extremes, to work long hours, to go without sleep, to hook themselves up to IVs instead of getting proper rest and nutrition, to keep going and going — all pressures Yibo has been under for a decade. We know he works long hours, we know he routinely pulls all nighters before these live performances, we know he’s collapsed before from overwork and exhaustion, we know, we know, we know.

The week before Yibo’s harness broke, photos leaked online of a hospitalized Zhao Lusi after she collapsed from a combination of exhaustion and malnutrition. She eventually opened up to her fans about struggling with depression and healthy eating, but before that, during the last half of December, the image of her post-collapse, pale and unable to walk, dominated social media and my brain. We had two stark, horrible reminders in quick succession that our immortal beloved idols are not immortal at all. They are so, so fragile.

A wonderful fan named Glitterati (follow her! Bluesky!) always kindly assembles a collection of fancams for her friends after any Yibo event, and normally I take the next day or two after the performance to go through them all slowly, savoring each one. It’s been nearly three months, and even though I downloaded the pack, I have yet to touch them. I thought that I would do it before I wrote this newsletter, but instead when I thought about it earlier I burst into tears. I hate that the safety incident has overshadowed Yibo’s tremendous performance of a beautiful, powerful song, and everything he wanted to say with it about nature and harmony within himself. I hate that he wore a goddamn pussy bow and maybe the best damn outfit I’ve ever seen and there’s a part of me that can’t even enjoy it because what if what if what if (Oh, mercy! to myself I cried)

I hate, most of all, the way I can’t hate any of this. And that’s because Wang Yibo left that stage, skipped down all the stairs, and then did this:

Why is he so cute?😭 https://video.weibo.com/show?fid=1034:5117938865209384

— Heike71 (@heike716.bsky.social) 2025-01-01T02:25:34.558Z

That’s right, he risked his life hundreds of feet in the air, then la la la hopped down from that whole deal like it was nothing and SWUNG ON THE CATWALK LIKE IT WAS A SET OF MONKEY BARS. And then fell, probably. Because. Yibo.

And then he went and got into ice climbing, which is much harder than anything he did in Exploring the Unknown, and scaled a glacier to fight climate change. Because. Yibo.

What can you do when confronted, not by the danger, but by the sheer unstoppable force of Yibo himself?

There is no bubble ensconcing him or us from reality — no conspiracy to make things look harder than they are so that Wang Yibo can come along and be the best at everything. There’s no filter, as much as we might wish for one.

There’s only Yibo, and himself, and everything riding on him and his own abilities at any given moment — and his trust in tools, and people, that sometimes fail.

What can you do? Absolutely nothing. Nothing except look on, hold him close to your heart, treasure every moment, cheer him on as he returns to Zhuhai later this week for another race—

—and hope that the god of Danger isn’t ready to change partners any time soon. 💚