The Girls Who Almost Made It: On Laura Palmer and Carrie White

Hey all, happy almost summerween! I’ll kick that off with my next post – which is also Friday The 13th Part 2, exciting times – but for this post, with prom season coming to a close, and Netflix’s Fear Street: Prom Queen having slashed its way onto streaming, I thought I’d discuss two of the most infamous queens of cinematic history: Laura Palmer and Carrie White.

This post has two charities that go along with it. The first, Laura’s, is RAINN, the rape, abuse, and incest national network. This organization provides round the clock support for survivors of sexual assault, including a 24 hour hotline. Please donate if you can. https://give.rainn.org/a/donate?_ga=2.85318425.1430710038.1748625923-1789252130.1748625923

The second charity, Carrie’s, is the YWCA, which provides resources like shelter, menstrual products, and other supplies to women escaping abusive situations, or who are experiencing homelessness. Again, please donate if you can, or volunteer. https://www.ywcacassclay.org/donate

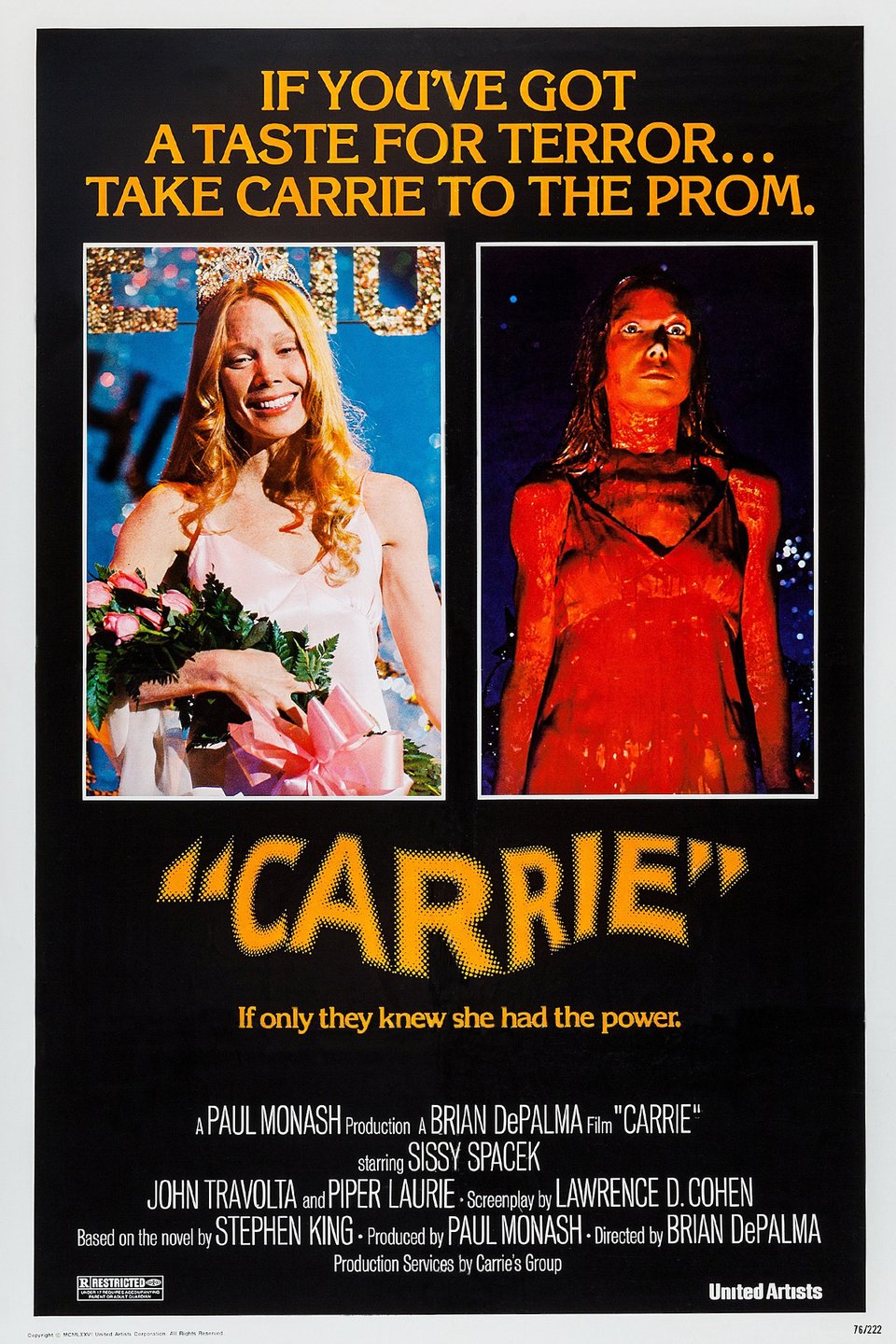

Laura Palmer and Carrie White are, as I’ve mentioned, two of the most infamous queens in pop culture history. The picture of Laura as Twin Peaks’ homecoming queen is one of the most recognizable visuals from the series, and the poster for Carrie, featuring first her joy at winning prom queen, then the devastation that follows, is similarly an iconic image. And, of course, their deaths are vital to both of their stories. But neither of those are the only things they have in common.

(IF YOU HAVEN’T SEEN TWIN PEAKS AND DON’T WANT THE MYSTERY SPOILED, TURN BACK NOW) (If you don’t care, keep reading.)

To begin with, both are in abusive domestic situations. Laura’s father, Leland, is revealed to have been sexually assaulting her regularly since she was twelve years old. Carrie’s mother, Margaret (whose actress is in Twin Peaks as the indomitable Catherine Martell) is an abusive religious zealot who beats her daughter, shuts her in a closet, and berates her for having normal bodily functions. Laura and Carrie both dread going home, never knowing what waits for them behind their front doors. Ultimately, this abuse leads to their deaths. Laura responds to her molestation by self-destructing. She falls into the dark world of prostitution, drug smuggling, and violence that simmers beneath Twin Peaks’ quaint, small town surface. She smokes, drinks, and sells her body for cocaine, to which she becomes addicted at the age of fourteen. On the surface, she is the perfect daughter, the homecoming queen, straight-A angel Laura Palmer. But her diary and her actions tell a much different story, one of a girl screaming for help, and no one coming, not even when it’s too late. Carrie, on the other hand, shrinks into herself. She is painfully shy at school, never interacting with other students unless they’re bullying her. She bears her mother’s multitude of punishments, because, until around the middle of her story, she has no other option. Carrie’s suffering made her small, someone who ducked her head and waited, held it out, until she could leave. Laura’s suffering made her wild, someone aggressive and scared, an animal gnawing its own leg off in a trap.

Both Carrie and Laura’s peers also – directly and indirectly – led to their deaths. It can be believed that if Carrie never went to prom, never got tampons thrown at her in the showers, never spoke to any of them, that maybe she would have made it out. It can also be believed that if one person in Twin Peaks actually tried to help Laura, to figure out what was wrong, that she would have made it out, too. But we know that’s not what happened in either case. Carrie went to prom, and a bucket of pig’s blood was dropped on her. Laura spiraled, taking her best friend and boyfriends with her, until she was killed. Carrie and Laura are kindred spirits in many ways, but especially this one. No one helped them, and everyone could have. And in both stories, their communities regret that, but only after their deaths. Carrie’s gym teacher and principal both lament at not having helped her sooner, not noticing just how scared she was. Bobby Briggs, Laura’s boyfriend, screams at the whole town at her funeral, telling them that they knew she was in trouble, and did nothing. And in that, the whole town killed her. Twin Peaks killed Laura, and Chamberlain killed Carrie, in the end.

And here we come to the great tragedy of both of these young women, the true grief in both of their stories: they almost made it. Laura died in February of her senior year of high school. Carrie died in May of hers. And for both of them, they had ways out after high school. Laura could have gone to college, or followed James Hurley on his motorcycle to California or Mexico, or wherever it is that he went. She could have found a way out from under her father’s control and made a life of her own, become her own person. If that bucket of pig’s blood had never dropped, Carrie might have been Tommy Ross’s girlfriend, or Sue Snell’s friend, might have gone to college with one of them and gotten out of her mother’s house. She might have used her sewing skills to start a business, or get employed somewhere. They were both months, weeks, even, away from freedom. And neither of them got there, instead being enshrined in the history of their towns as the girls who died and who killed, who were forever eighteen, and stuck so many others in the same place.

Carrie and Laura had different, but similar, fates after their deaths, even. Laura became a sort of angel to Twin Peaks, a saint, a poor, perfect girl lost too soon. Even with the revelations her death, and diary, brought, she was martyred in the minds of the town. But to Chamberlain, Maine, Carrie White was a monster. She killed those kids with her devil-magic and destroyed Chamberlain forever in one fell swoop. Carrie White burns in Hell, and Laura Palmer smiles forever from a perfectly-maintained trophy case, a shining angel in white.

And now there is the final thing that binds these girls together, links them in the cultural zeitgeist forever: hope. Both Laura Palmer and Carrie White are hopeful up until the very end. They both think they can make it, know they could. Carrie, in her brief moment of victory at prom, sees a future for herself where she is allowed to be a girl, where she can be pretty and successful. Laura never gives up on finding out who BOB is and escaping him, defeating him. She writes to him, threatening him, fighting him, throughout her life. It is only in the moment that she dies that all the hope leaves her eyes, but even then she thinks that her death will kill BOB, and in that, too, she has hope. Even in the darkness of abuse, the undefeatable cycle of power that forces them into submission, Laura and Carrie have hope for a better future for themselves, which makes it all the more tragic that that future never comes.

But what can we take from this? What do we do with these girls and their sorrow, with the knowledge that they would never really get out, so doomed by the narrative they were? What do we do with the fact that their stories, the stories of Laura Palmer and Carrie White are the same as of so many women and girls in real life who dread their homes and their families, whose bodies aren’t theirs anymore?

I don’t know for sure, but I think what we can do is remember. Remember Laura and Carrie, and remember that most of the reason they died is because they weren’t helped. Remember to help, and to notice, and to empathize. And remember that all characters, and all stories, are grounded in something real. Laura Palmer and Carrie White may not be real people, but there are real people who are Laura Palmer and Carrie White, and that can never be forgotten.

Thanks for reading all! Sorry for the short post, I’ve been editing my book for which I have a pitch meeting in two weeks! The next post will be Friday the 13th Part 2, and then onto Summerween, with summer slashers and more to keep you entertained through the hottest months of the year. Until then, happy reading, and stay spooky! 👑🩸