Kids These Days Don't Care About Living Deliciously Anymore

Hi all and welcome back to week two of the 2025 So Desensitized Spooky Season Spooktacular! Wrapping up this week we’ve got Robert Eggers’ The Witch, and then next week we’ll have some literary ladies with Grady Hendrix’s Witchcraft for Wayward Girls and Maggie Stiefvater’s The Raven Cycle. Happy reading, stay spooky, and go to your local library!

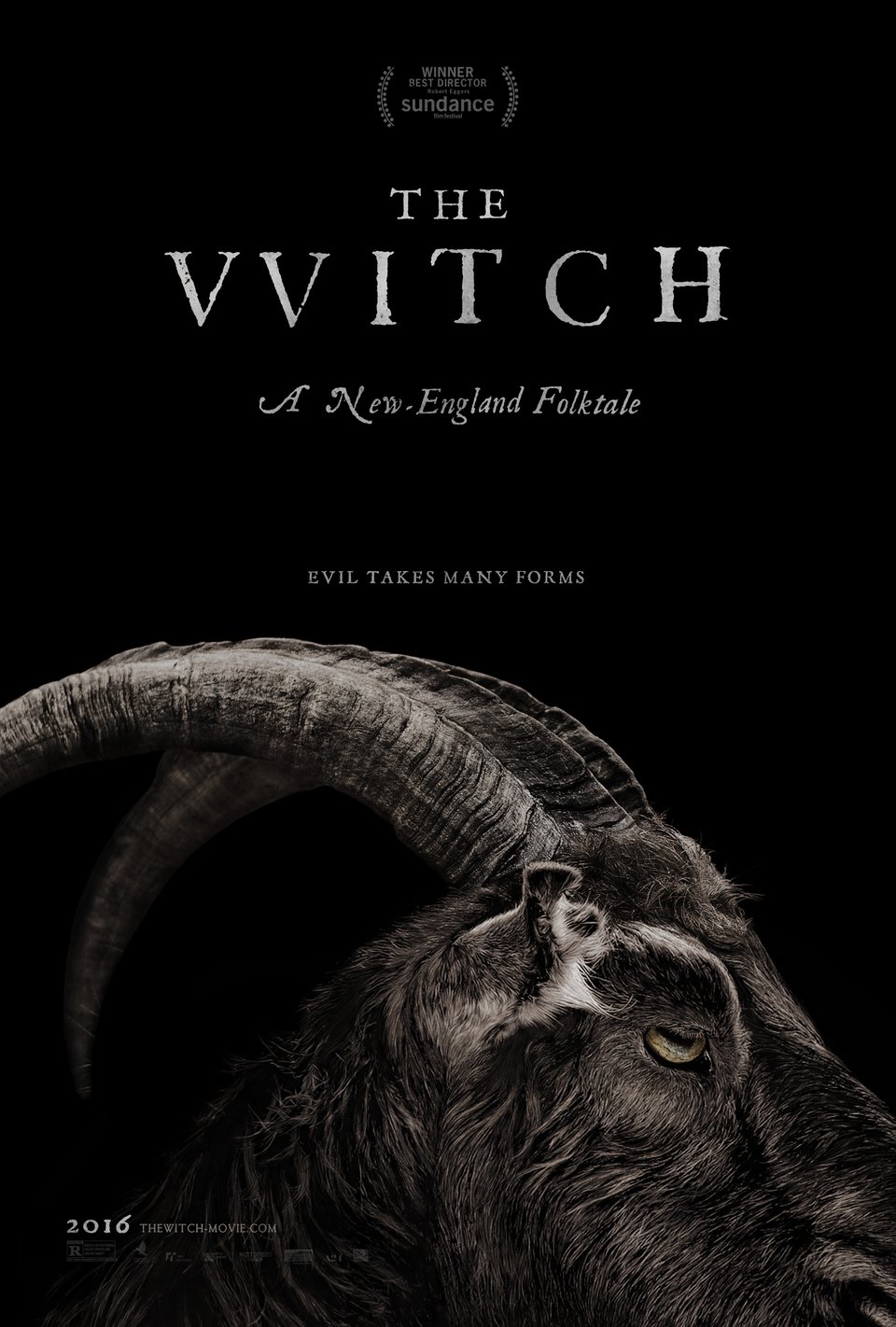

There are some directors that have kind of a signature style of movie that they just go insanely hard with ever time. Robert Eggers is undeniably one of them. One thing that man will do is direct a beautiful, haunting gothic horror story. His most recent movie, Nosferatu, is, of course, no exception to this rule, but he’s been creating masterful gothic horror since his feature debut in 2015, with The Witch. Taglined “A New-England Folktale” The Witch is isolation horror at its finest, detailing the descent of a puritan family into madness after they are banished from their colony, while grappling with the realities of witchcraft in seventeenth-century New England. Which are complicated, to say the least.

Perhaps the most famous witch-related event in history, the Salem Witch Trials, occurred approximately sixty years after the time The Witch is set in, and were the result of wheat-induced mass hysteria and, ultimately, boredom. But superstitious about witches didn’t begin and end with the nineteen women murdered there by any means. The Salem Witch Trials were simply a cataclysm of tensions that had been building since the colonies were settled, likely even before then. These superstitions are fairly well-known today, coupled with superstitions that actually originate in the very witchcraft prosecuted in those ‘trials’ - throwing salt over your shoulder, knocking on wood, etc. But what most people think of puritan beliefs, specifically about witches, is that they came not from a place of genuine belief, but from a fundamental misunderstanding of how the world works. Some call it stupidity when what it was is belief, same as any that there is today. And The Witch shows that perfectly.

The thing about puritan belief in witchcraft that is vital to a modern understanding of The Witch is that malevolent witches that wilted crops and stole babies were as fundamental to their belief system as gravity is to ours. It was simply a given, a fact that everyone knew. There were foundlings. Children could be ‘witched’ and die. Only God could save your soul from witchcraft, and even that wasn’t certain. Witchcraft was not something to be taken lightly, not something to tease siblings with, even. We know now that really, the colonists just didn’t know how to handle New England winters or farm properly. Their crop rotation skills were nonexistent, leading to decrease in the quality of crops over the years. And they needed something to blame it on so it was, as it always is, women.

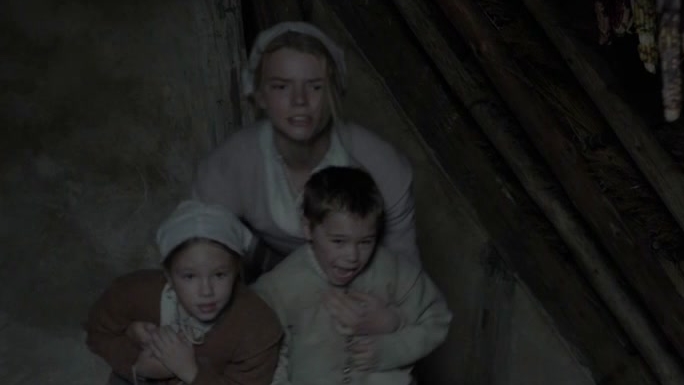

What sets off the events of The Witch is the vanishing of baby Samuel while he is being watched by his sister, Thomasin. This sows paranoia in the already frightened family as winter closes in, causing them to turn on each other with threats of witchcraft as serious as death. As the movie goes on, it is unclear whether there is really a Witch of the Woods, or if the family is just slowly going insane as a result of the isolation they have been placed in. Turns out, it’s a horrifyingly bleak combination of both. There really is a coven of witches in the woods that stole baby Samuel and bewitched Caleb, the eldest son. But none of the family were ever really witches when the crops began to rot, or when the baby was taken. Only Thomasin was ever a witch, and only after she lost everything.

When I said that accusations of witchcraft were as serious as death, I meant it. Everyone in the family dies, except Thomasin. Her own parents try to kill her, and allow her siblings to die after forgetting their prayers in a moment of fear as they attempt to exorcise Caleb of the witchery. They’ll believe anything, even Thomasin’s accusation that the goat, Black Phillip is possessed by Satan and Jonas and Mercy commune with him at night. Which she is mostly right about, but should have sounded insane to her parents. The fact that they were so ready to believe it speaks to their paranoia, so extreme that they would even kill their own children if they believed them to be in anyway associated with witchcraft. So, given this knowledge, why would Thomasin make her parents believe her younger siblings were witches?

Thomasin is a very complex character in a lot of ways. The eldest daughter of a family banished for not following the beliefs of the colony’s church, she is tasked with most of the jobs around the farm, from taking care of the new baby, to doing the laundry. There is something strange about her from the beginning, but that can easily be written off as anger at her family’s state, or at her family members themselves for making her do more than she ought. But when the shit hits the fan, she pushes the family further towards destruction, accusing her siblings of communing with the Devil, calling herself the Witch of the Wood, and allowing Caleb to go into the woods, where he is witched. Though she seems like the most rational of all of them as her mother sets up her dead sons for bed before trying to kill her eldest daughter, and her father locks his three remaining children in the barn with a murderous goat who he believes to be Satan, she is the one who falls to the insanity the fastest, suggesting that maybe she was slipping before they were banished, long before Samuel was stolen and the crops failed. Of all of them, Thomasin is the one who is willing to do the most to survive, even going so far as to kill her own mother when her life is threatened.

The Thomasin we see at the end of the movie is, by all appearances, a completely different person than the one we saw when the movie. Naked, covered in her family’s blood, and signing a pact with the Devil to dance naked with the other witches of the woods for eternity. But I don’t know how far removed she ever was from that. She was clearly always strange, someone who was drawn to the darkness, who would play with a baby at the edge of the woods, who would call herself a witch just to frighten her sister, which, remind you, is no small thing for the time. If anyone was to become a witch, it was going to be her. Even her father, the most immediately gone, entertained the idea of returning to the colony when things got too bad. Thomasin starts the movie tired, and ends it empty. Everyone else starts out relatively normal for the period. A man who would rather his family be banished that bow to the rules of the church was not uncommon in puritan New England. It’s why we have Rhode Island. But witches were never as common as all that. They were only ever women who were in the wrong place at the wrong time when there was blame that needed to be placed.

So look at Thomasin in the warmth that never light her family’s farm. Watch her join the circle, sign the contract with Black Phillip, let her hair fall around her shoulders. She is the one who will steal the babies now, the one who will make the crops fail. Maybe she always was, who’s to say? Maybe, when she turned to the twins and asked, with such exhaustion, if they were witches, she really meant it as an apology for ever suggesting they were, knowing that it would lead to their deaths. Maybe she was just trying to take the blame off herself with her screaming and crying and praying and finger-pointing. Maybe she only ever meant to get off the damn farm.

Evil takes many forms, as the poster proclaims, and some of them are puritan patriarchs who want nothing more than a reason for what’s happening to them. The point of the movie is not about whether or not Thomasin is a witch, nor is it about whether or not there even was a witch. It’s about how fundamental and dangerous puritan belief in witchcraft was. Everyone on that farm, Thomasin included, might have just genuinely gone insane. Samuel might have been taken by a wolf, Caleb by poison, or a fever. They all could have died for nothing. Or Thomasin could have done all of it, or none of it, but got out in the end, free in the woods forever. Thomasin could be dead, just like the rest of them. But whatever it is, remember: witchcraft accusations were deadly serious, and led to the murders of countless innocent women throughout the years. It doesn’t matter whether or not she was a witch, because they would have killed her anyway. Everybody floats.

Thanks for reading, all! This was a bit of a hard one, because the movie does a lot of talking for itself, so I really do suggest you all go watch it still. Preferably somewhere dark, because the exposure is really awful. Happy reading, stay spooky, and I’ll see you next week for some bookish discussion! 🐐🪵🧺🔪🩸