Fearmongering: Part One

Horror and War: 1914-1945

Happy Friday, everyone! I’m back after a good long hiatus to tell you about the historical importance of horror! The idea for this series is one I’ve had for a while, and this recent election and upcoming inauguration just solidified its relevance. This series will be four to six parts long, and will come out on the standard once every two weeks schedule, with a little break in the middle for Valentine’s Day, where I will write about My Bloody Valentine if I can get my hands on it. Happy reading, and stay spooky!

People have been telling scary stories since the dawn of time, and filming them since the dawn of film. George Melies’ La Manoir du Diable, or The House of the Devil, was filmed in 1896, making it the first ever horror movie. It was followed by others like Alice Guy’s Esmeralda, and Frankenstein (1910). Then, in 1914, World War One began, and the world was changed forever, as were the movies in it.

There weren’t many movies made during the war, and, as such, not many horror movies. The only one I’ve found before 1920 is the 1915 German film The Golem. Things really picked up following the end of World War One, with movies like The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and, the movie that I am going to focus on for this next little section, Nosferatu (1922).

One of the things that made World War One as horrific as it was, was that there hadn’t really been mass death like that before. With tanks, gas, and other such atrocities introduced into battle, people were dying on the battlefield like never before. And the ones who didn’t die came back destroyed in a different sense, having witnessed death on a scale that no one should. Many filmmakers assumed, during that time, that those returning soldiers wouldn’t want to see horror movies. That they wouldn’t want to see that kind of death reflected back at them. They were wrong, and Nosferatu proved that.

Nosferatu was an unlicensed filmed version of Dracula, with a few changes. The main one being that death, instead of love, was the main theme. Count Orlok brings the plague with him, leading to mass death. Erin is often silhouetted by a graveyard, as seen in the picture above. Death like that was, almost ironically, what soldiers wanted and needed to see after their time in the war. Nosferatu’s wild success shows that death should not be a taboo because people ahve experienced it on a level that hadn’t been seen before - it should be the opposite. Soldiers returned from World War One with an immense feeling of disconnect from the people around them who hadn’t ever known such horrors, and, as such, many struggled greatly with being home. Movies like Nosferatu showed them that death through supernatural means, doing what horror has always done - portraying societal fears in a way that is safer and easier to engage with than the real thing. The people in Nosferatu were dying at a scale similar to that of the War, but of a supernaturally occuring plague. In many ways, Nosferatu made the death that came of the War more approachable, by showing it in such a contained and easy to understand fashion.

Unfortunately, horror had a bit of a decline in the years following Nosferatu. Many major motion picture companies decided that to show death and horror on the big screen was tasteless, something that no self-respecting producer would be caught dead doing. There were a few horror movies in the roaring twenties, like The Phantom of the Opera, but for the most part, people seemed to want to forget about the War as much as they could, enjoying their parties and Charlestons. The War was a thing of the past, as was horror, and it would stay that way for almost a whole decade, until a producer’s son at Universal Pictures had an idea that seemed, to everyone else, both insane and impractical:

What if Universal adapted Dracula for the silver screen?

The producers hated the idea, but he somehow convinced them. And so, the Universal Monsters were born. Dracula was played by a poor Romanian actor who had never learned to speak English properly, and was then rocketed to fame as he became one of (if not the) most famous movie monsters ever. Frankenstein followed soon after, doing the same thing to Boris Karloff as Dracula did to Bela Lugosi, then The Mummy, then The Wolf Man, and on and on, spawning one of the most famous franchises ever. Dracula had a son, Frankenstein had a bride, a giant ape attacked Manhattan, and all hell essentially broke loose.

Now, the Universal Monsters are wildly interesting in the ways in which they reflected society’s fears at the time. Dracula, the first movie of the ongoing franchise, was released in 1931, and fed into two fears that would be repeated again and again in the rest of the Universal Monsters movies, as well as just about every horror movie to come after. The first of these fears is isolation.

Isolation is a main theme of the original text of Dracula, in very large part due to Bram Stoker’s homosexuality, and feelings of isolation as a result of being gay in the 1800s. Universal’s Dracula also has themes of isolation, but this time, they call to soldiers’ feelings of loneliness and disconnect following their return from the War. As mentioned before, the soldiers that made it back from the trenches were forever scarred, and unable to communicate exactly how horrible what they had experienced was. Dracula reflected that disconnect right back at them, just like Bram Stoker’s novel had done to him when he first wrote it, just for different reasons. The trauma and madness Renfield endured and exhibited were also, however slightly, reminiscent of those same soldiers’ shell shock and PTSD.

Dracula also played right into fears of the unknown and foreign that came from the War. Bela Lugosi’s casting, while a thing I get kind of feelsy about in the sense that it made this poor Romanian kid who couldn’t speak English more famous than anyone else, also made villians of people like him. Dracula was scary because he was from a foreign country, where they spoke differently, ate differently, and muttered about demons. Bram Stoker’s story also, disappointingly, has elements of this distrust of foreigners as well, with random casual racism about the Romani people thrown in there from time to time, as well as general muttering and suspicion about throughroughly harmless customs and religiousity. But those fears were all the more amplified in 1931, when the U.S. had just had fought against a whole bunch of Eastern European countries, where people looked and spoke like Count Dracula. The idea of a nice, hardworking young man going away to a foreign country and coming back shaky, raving with warnings and terrors, hit very very close to home in 1931, as did the nice young couple fighting against that very force that had ruined that man in a desperate bid to keep their lives their own.

Dracula set the stage for all monster movies that followed, all of which held those same fears carefully, and spoon-fed them to audiences. The Mummy is a prime example of a '“foreign evil”. The Wolf Man is alienated from his community and eventually killed for his condition - which, may I add, was brought on by an injury. The Creature From The Black Lagoon waded up from a swamp to prey on nice young women. Frankenstein wandered the countryside in a daze, killing innocent people, completely disconnected from reality. The Universal Monsters were the perfect vehicles for the fears that consumed society after the War, as evidenced by their longevity and commercial success.

Unfortunately, save for The Wolf Man, horror movies in the 1940s were decidedly schlocky, with movies like The Ghost of Frankenstein, House of Dracula, and She-Wolf of London. This is likely due to the ongoing World War Two, which was ravaging the world. No one and nothing benefits from war, and art most definitely suffers.

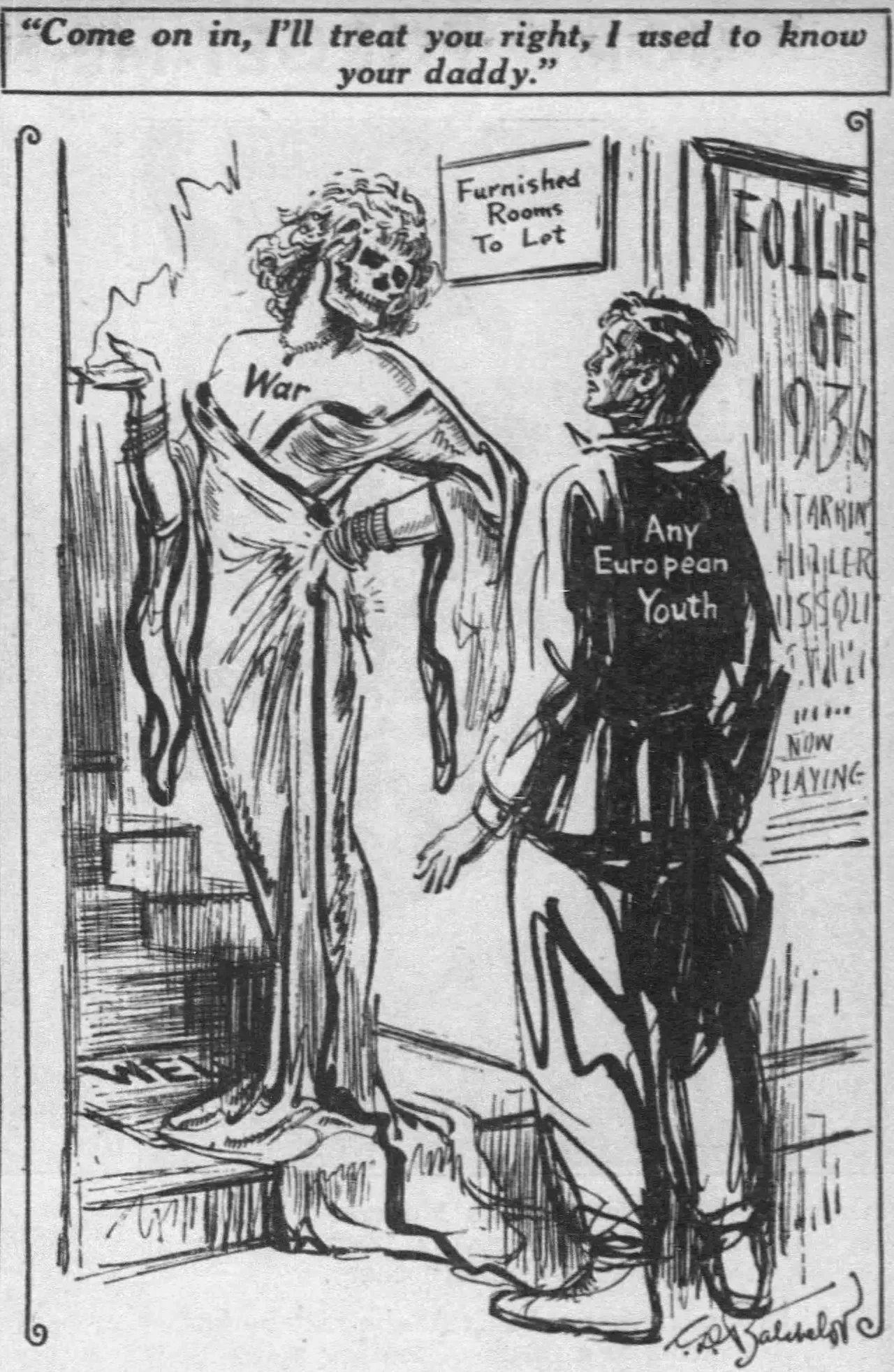

World War Two managed, to the despair of everyone, to be worse than World War One. The Nazis were taking control of Europe, Communism was spreading, and propoganda and racism were at an all-time high. In fact, an awful lot of war propoganda at the time looks like it was designed for a horror movie marketing campaign. And, in many ways, it was. Because war is horrific, more horrific than anyone should imagine. It is careless and cruel, so much so that it requires propaganda campaigns on a huge scale to convince anyone to even consider signing up for it, especially after their fathers just went through it and either came back destroyed or didn’t come back at all.

World War Two raged for six years, ending with the creation of a weapon of mass destruction the likes of which no one had ever seen before, and would be the source of cultural nightmares for decades upon decades to come: the nuclear bomb.

I hope you all enjoyed that first little look into the historical importance of horror! It’s harrowing stuff, and I hope you’ll all stick with me on this journey.

Now, as I’m sure many of you know, in a very sad turn of events, David Lynch died yesterday. He was the director of Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, and Twin Peaks, just to name a few. He was a truly great artist, whose work changed my life. There were a lot of contributing factors to the creation of this blog. It required a very particular kind of confidence in my writing, and, more than anything else, in the stories that I write about. David Lynch, and his stories, creations, and thoughts about creating, was, and still is, one of those factors. He is dearly missed. As such, this post’s charity is The David Lynch Foundation, which seeks to help women and girls who have been raped or sexually assaulted heal and regain their autonomy through transcendental meditation. Please consider donating if you have the means to do so. https://www.davidlynchfoundation.org/invest.html

I also have a little homework for you all: go consume something David Lynch made. Watch one of his movies. Listen to some of his music. Watch his weather reports. Watch Twin Peaks. See what beautiful things he created. You’ll like them.

Thank you for reading, and stay spooky! 💖🩸