Fearmongering: Part Four

Horror movies, their relevance, and their impact from 1980-2000

Hi all! Welcome back to another edition of Fearmongering, brought to you by my attempts to keep busy and not check my email! Sorry it’s late, there was so much to cover and I’ve been busy! This is a big one, so buckle up. Up next is the last part, which will cover 2000-now, as well as wrap up the whole series and tie it all together into the modern day. After that, my next post will be on Friday the 13th, and will be about Friday The 13th Part Two if the library has it. If not, it’s a surprise! Then, with the one year anniversary of So Desensitized coming up at the end of April, I will republish an old post, with some extending and revamping. Since the comment section isn’t working, please just let me know which one you want of the list proposed in the last post if you know me in person. If you don’t, I apologize, you are at the whims of various North Midwesterners and also my family. So, with all that coming up, let’s dive in to the penultimate chapter of Fearmongering!

[This post’s charity is The Red River Theatre Organ Society! The Fargo Theatre, my local independent movie theatre, is celebrating its 99th birthday today, and the RRTOS is quite literally the reason it’s still standing. They’re trying to install new pipes this year, so they need some help! Please donate if you can! https://www.rrtos.org/donate ]

The sixties were a difficult time when America was in upheaval. The seventies were a difficult time when America was in upheaval. The eighties were…not better. The AIDS epidemic was in full swing, Ronald Reagan was president, and, apparently, the most under-threat group in the U.S. was middle to upper middle class white teenagers.

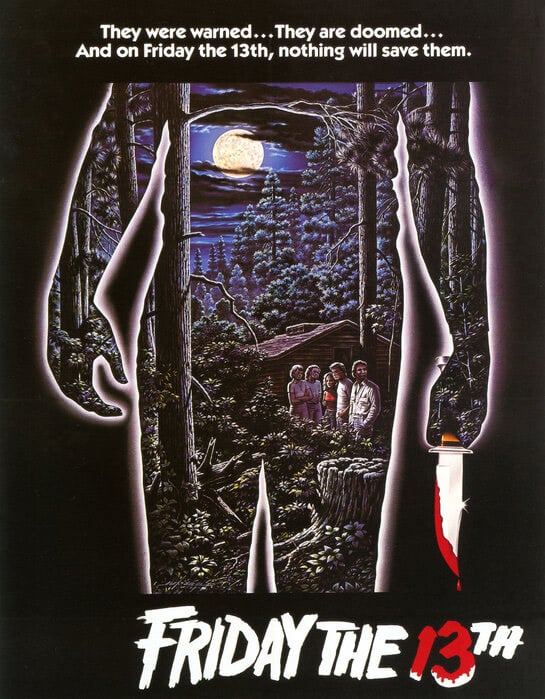

The eighties represented not just a boom in almost every horror genre, but the invention of a new one: the modern slasher. While there have been slasher movies since Psycho, the eighties brought the formula that we all know and love. The first two modern slashers, Halloween and Friday The 13th, were, in a way, the final capitalization on the Tate/LaBianca murders. A knife-wielding killer preying on white, suburban teenagers, specifically girls, struck a chord built on The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Black Christmas, and The Exorcist. Friday The 13th was released on May 9th, 1980. Then, in June of 1981, the first cases of HIV/AIDS were recorded in the U.S., and blood and sex became dangerous.

The Tate/LaBianca murders to AIDS epidemic as represented in horror movies pipeline is pretty simple, as these things go. The Tate/LaBianca murders resulted in the widespread fear of “crazies” that could be anywhere, influencing or killing even the children that were as protected as protected could be. An invisible fear of sorts, the fear of a mindset, a bad influence. This was, as discussed in Fearmongering: Part Three, the reason for movies like Texas Chain Saw and The Exorcist, where white children were the ones in the most danger of all. This trend continued into Halloween and Friday The 13th, but with more knife-based violence, further playing into the murders, and less into the various protests and movements of the sixties. Then, that kind of knife, blood, and sex-based violence turned out to translate very well to growing societal fears of blood and sex that came of the AIDS epidemic. Suddenly, what parents of teenagers had to fear was sex, drugs, and blood.

The best two examples of the modern slasher movie by way of the AIDS epidemic are, I think, A Nightmare On Elm Street, and Sleepaway Camp. Sleepaway Camp was first, being released on November 18, 1983. It was an attempt at capitalizing on Friday The 13th and the rising summer camp slasher phenomenon, but far, far, weirder. It has absolutely Looney Tunes-style kills, like a pot of boiling water being pushed onto a cook, and a hornet’s nest dropped on a bully. It also contains one of the most infamous twist endings in all of horror history, where it is not only revealed that the killer was the protagonist, Angela, the whole time, but that she’s been a boy the whole time, too. The ending of Sleepaway Camp felt like the ultimate betrayal of the audience’s expectations. Not only was the hero the killer, she was part of a group of people who were beginning to be some of the most feared and reviled people in America. Queer people were becoming monsters to society, carriers of a new and horrible disease, and horror movies were showing that aspect of the AIDS epidemic, too. Sleepaway Camp isn’t what could exactly be called a blockbuster, more like a cult classic, but it still had a not insignificant impact on horror movies, and the opinions of young people in particular. It was the dare movie, the one where you got to see a penis at the end, the one with the wacky kills and the wackier killer. But, however many young minds Sleepaway Camp managed to shape, it has just about nothing on A Nightmare On Elm Street. If Sleepaway Camp was the dare movie, Nightmare was the double dare movie. Because it’s not wacky. It’s scary as hell. Wes Craven brought the nightmare of AIDS to movie theaters, video rental stores, and basement VHS players all around the country. Freddy Krueger exemplified almost every fear that came with AIDS. He attacked where kids were supposed to be most safe when parents were out of town. Nothing was done until it was too late, partly as a result of inattentive parents, partly because it’s hard to tell what’s happening to someone if it can’t be seen on the outside until the very end. Freddy Krueger is strangely feminine, as many eighties and nineties slasher villains are, portraying the monstrous queer that emerged all over media as a result of AIDS. And not only that, he is written in a way that suggests pedophilia. He attacks children specifically, used to work in a school where he’d be close to them, and attacks in ways they can’t communicate to their parents. He was, in fact, originally written to have been a child molester, not a child murderer, but Wes Craven was asked to remove that plot point from the script after a case of real life molestings done by an employee in an elementary school. Point is, what we in the modern day think of as a slasher movie was built on the fear of not just AIDS, but queer people in general, with many well-known slasher villains being distinctly feminine or otherwise queer-coded in some way, a trend that would continue for a long while after Angela Baker and Freddy Krueger were introduced to moviegoers.

The eighties are also considered the birthplace of body horror, for what I hope are obvious reasons (still AIDS). David Cronenberg was at his finest, with movies like The Fly, Dead Ringers, and Videodrome critiquing societal obsessions with sex, violence, voyeurism, and TV screens. This obsession with voyeurism is also warned against in David Lynch’s 1986 masterpiece Blue Velvet, which would begin to set the tone for nineties horror movies to come. John Carpenter, another one of the all-time horror greats, also came out with The Thing in 1982, which is about an isolated group of men that are exposed to a blood-borne virus that can only be diagnosed by a blood test or a horrible death and slowly falls apart from distrust and incompetent authority figures. He’s a subtle kind of guy, Carpenter. And all of these but Cronenberg’s are still pretty early in the eighties. The later eighties managed to get even weirder.

A lot of movies in the late eighties were still slashers, alien invasion, or body horror movies. Or all three at once. But they were getting real weird. Redheaded dolls were killing grown adults, for one thing. And there were also starting to be an awful lot of vampires. While the standard sort of modern AIDS-based slasher was definitely not going away any time soon, vampire movies were starting to catch up. Now, monsters in general abounded, no question about that. Killer Klowns, Xenomorphs, and Predators rampaged through screens around the country, but vampires were undeniably holding their own. In particular, the 1987 cult hit The Lost Boys really highlights the eighties vampire and his implications.

The Lost Boys has everything the average viewer wants from a vampire movie: goth music, hot goth Kiefer Sutherland, AIDS implications, and weird, not quite committed-to moralizing about marriage. Vampires have been queer-coded since their beginnings in media, and that only increased during and after the AIDS epidemic. In Dracula (the book) Renfield says that “The blood is the life”, which is sort of the basis of all vampire legends. So what does that start to mean when blood becomes death? The vampires of The Lost Boys are very notably teenagers as well, and prey on other children and teens. Combine that with cultural fears of blood, add a single mother who ends up dating a vampire, and you’ve got yourself a nice little fearmongering cocktail. There’s been moralizing about marriage in horror movies since before even Psycho. Chris MacNeil is divorced in The Exorcist, there’s no mother at the cannibal dinner table in Texas Chain Saw, and the mother in The Lost Boys moves her two children out to Santa Carla because she’s just gotten divorced, unknowingly putting her children directly in the path of the vampires that run the town. And not only that, those vampires do seem a little gay. There’s only one woman in the group, and none of them but the protagonist, Michael, seem interested in her in a romantic sense, as she’s treated more like property than anything else. This trend of queer-coded vampire movies continues into the nineties and beyond, building on the fears of blood created by AIDS.

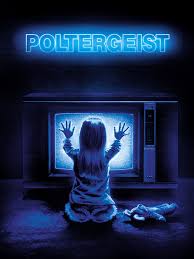

In a brief aside, the eighties also marked the arrival of horror movies that were allegedly for children. Poltergeist, Ghostbusters, and Gremlins all marketed themselves as PG, scary, but not too scary to take a kid to see. They were, in fact, decidedly too scary to take a kid to see. As a result, the PG-13 rating was introduced in 1984, mostly because of Gremlins and Poltergeist. This brought an absolute wave of family-friendly spooky movies in the nineties.

The early nineties came with not only somehow more vampire movies than the eighties, but with a wave of, novelly, TV shows. With shows like Twin Peaks, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, and The X-Files, horror was making its way to the small screen. Twin Peaks in particular was the television event. It changed the way TV worked forever from the moment its legendary pilot episode aired in April of 1990, inspiring TV and film makers forever after. Twin Peaks, David Lynch, and the prequel film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me introduced surrealism combined with real world darkness to film that would be expanded upon later on, in the 2000s.

At the same time, family-friendly horror movies like Hocus Pocus, Casper, and The Addams Family were sweeping the nation, giving kids safe entries into the realm of horror where Poltergeist and Gremlins did not. This phenomenon is what made many current horror film makers the artists they are, without traumatizing them in the process. Twin Peaks is also often mentioned by modern horror creators as an experience that greatly shaped their work.

In tandem with this wave of family-friendly horror came the rise of horror subgenres that were more welcoming to bigger audiences than the splatter of the eighties had been. Horror comedies were huge, suggesting not just an increased national sense of dark humor, but a decrease in taking things all too seriously. Even a lot of very good horror movies that aren’t comedies would be ridiculous if they were acted or written by anyone other than the people in them, and the nineties took that fact and ran with it in movies like Frankenhooker and Death Becomes Her. Romantic horror movies were also at an all-time high as Francis Ford Coppola gave the public a Dracula who crossed oceans of time for love, and Practical Magic is a story about witches, yes, but more a story about love and sisterhood than anything else. Horror was, in places, becoming gentler, and more welcoming to more kinds of people in the nineties. This is largely due to the nineties as a whole being a brief moment of general peace and prosperity for America. The Cold War ended in 1991, essentially putting an end to the fear of the atom bomb that had petrified America since its invention. There were fewer alien invasions and giant monsters. Instead, horror movies began to focus on more interpersonal, psychological fears. And there were still an awful lot of slasher movies.

In the early nineties, horror movies started tending more towards psychological fears than bloody ones. Skepticism around queer people still carried over from the eighties, but the blood didn’t so much come with it anymore. Horror movies were becoming more analytical, clinical, or elevated in some other way. Horror was starting to see some critical acclaim - Misery and The Silence of The Lambs notably won Oscars, a rarity for horror - but many horror movies weren’t being called horror movies anymore. They were thrillers. Taking inspiriation from book marketers in the sixties, critics began taking horror movies that were considered “elevated” in any way and labelling them “thrillers” to cover up the fact that horror movies could have any kind of cultural or societal value. The Silence of The Lambs in particular, while an absolutely horrifying movie in many ways, is still called a thriller by many people. The Silence of The Lambs is, in a way, the perfect early nineties horror movie. An adaptation of Thomas Harris’ 1988 novel of the same name, it brings the analytical, investigative genre to horror that also shows up in Twin Peaks and The X-Files. With Clarice Starling comes a new kind of final girl, the professional kind, who doesn’t do any of the screaming or fussing that the final girls before her did. Hannibal Lecter is a novelty, a smart serial killer, a doctor even, further playing into the idea that a serial killer really could be anyone. And Buffalo Bill rounds it all off with some good old fashioned queer monstrosity, kidnapping women and stealing their skin. The Silence of The Lambs acts, for all intents and purposes, like it’s setting the stage for all horror movies to come, at least for the decade. But, while it did inspire many horror movies later, it didn’t quite herald anything for the nineties.

Horror movies in the latter half of the nineties are generally either psychological and strange, or distinctly violent and campy, or both. The Child’s Play franchise released its fourth installment, Bride of Chucky, in the same year that Ring (which would be Americanized to be The Ring in 2002) came out, and I think that about sums it up. Slashers were still running amok, just on a slightly smaller scale than before. And at the same time, goths were having a pretty great time at the movies. The Craft, a movie about teenage witches that makes several interesting points about young women’s bodies and contains more black babydoll dresses per frame than any Hot Topic has ever even dreamed of, hit theaters in 1996, just two years after The Crow. Blade, Edward Scissorhands, Sleepy Hollow, and Death Becomes Her added to the growing repertoire of truly excellent, extremely gothic stories gracing the silver screen. Then, in the same year they costarred in The Craft, Neve Campbell and Skeet Ulrich starred together once again in a movie that would fundamentally change the genre forever. The year was 1996. The movie was Scream.

Scream was the slasher genre tipped on its head by one of the men who invented it. Wes Craven, who directed, among other things, The Hills Have Eyes, The Last House on The Left, and A Nightmare On Elm Street, made the first ever meta-slasher. Scream, and the characters in it, understood the genre they were in. They were even fans of it. And they died anyway. Scream looks back at the eighties, at the slashers, the AIDS, the sex, the blood, the kids in danger, and twists it beautifully. Scream was a sign of what was to come when The Silence of The Lambs wasn’t quite. Wes Craven understood exactly the impact the genre had had on culture, and decided to subvert it. Scream made a culture recovering from an epidemic, from the threat of nuclear war, from murder and violence look at itself and what it had welcomed during that time of fear. It shows how strange and silly slashers became after a while, but also how scary they are. It acknowledges the “rules” of slasher movies, then violates them. It doesn’t shy away from killing those kids, makes their deaths ironic and tragic at the same time. The franchise is still ongoing, in fact, with increasingly unhinged casting announcements coming out for Scream 7 as I write this.

So, Scream brought the slasher genre full circle on itself in 1996. Which begs the question: what’s left for anyone else to do? Well, a lot, as it turns out.

At the end of the decade, in 1999, a seventy eight minute long movie with a sixty thousand dollar budget changed not only the way horror movies were made, but how they were marketed, forever. It introduced a subgenre of horror that had, up until that point, been mostly underground, into the mainstream. It had a marketing campaign that was so revolutionary that some people believed the movie they were about to watch was real. (That said, the internet was only just taking off, which made that a lot easier.) You guessed it: it’s The Blair Witch Project.

Thanks for reading, all! As mentioned before, this is the penultimate Fearmongering post, then we’re back to your regularly scheduled programming. For the one year anniversary, I will be republishing an old post, with your input! Here’s the list, I understand the comments don’t work, so just tell me which one you want if you know me in real life.

Psycho (First ever post!)

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Most popular that’s not Psycho!)

The Exorcist (My favorite!)

A Christmas Carol (An extended version of this post has been professionally published, so I would publish that extended version here!)

Vampires: What’s the deal? (I just had so much fun with this one, and could add Nosferatu to it!)

Thanks for reading, please get the word out about this series, and stay spooky! 🩸🔪💚