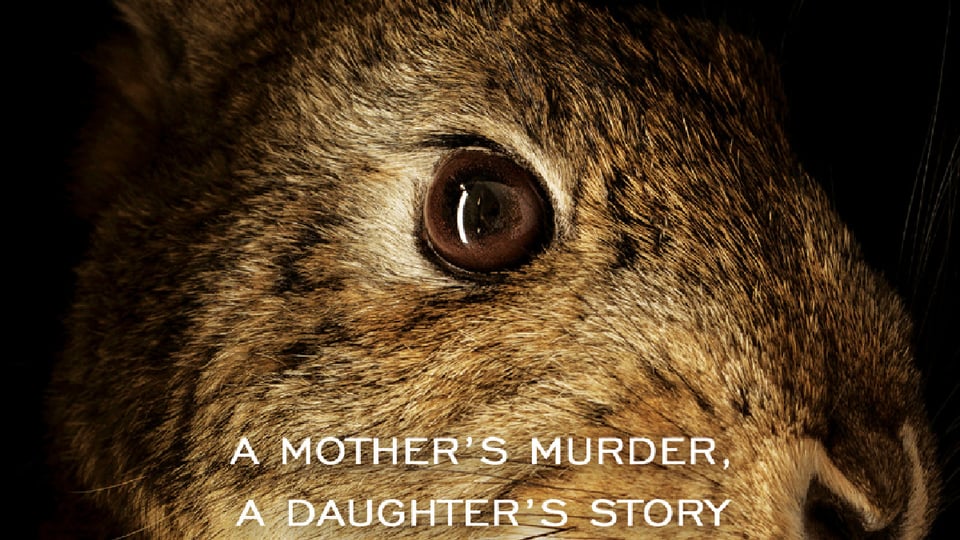

Rabbit Heart is a sharp look at crime-related trauma

the true crime that's worth your time

Best Evidence supporters can read the full article via newsletter, while folks with a free subscription can click through to read this review

Kristine S. Ervin's mom wasn't killed in a high-profile attack that lends itself to a series like Mindhunter, nor is her killer likely to end up as a Ryan Murphy Monster (colon) subject. But her new memoir, Rabbit Heart, serves to remind us that violent crimes are far more than the stuff of procedurals or dubiously intended comedy podcasts. These deaths leave a wound on the world. Looking past that, to the (oft media-created) "glamour" of the monster is an intentional avoidance of the point.

We talk a lot here at Best Evidence about centering crime's survivors and/or those lost as the result of crimes, so books like Ervin's (which was released by Counterpoint Press in March) feel especially crucial. The great news is that it's also a beautifully written, immersive read. That feels uncomfortable to say, given how personal and gut-wrenching her experiences have been: how does one ethically evaluate a tale of real, first person trauma as a piece of "entertainment"?

My approach, so far, has been to pass on writing about the books that were probably a therapeutic catharsis for the author, but pose challenges as an unrelated reader. The coward's way out, I know. But working through those books makes me appreciate Ervin's handling of her and her mother's story all the more. Writing about other people's damage for an audience is easily done, with the right set of skills and a good editor. Writing about your own can verge on impossible.

But Ervin makes it feel easy, though we know it's not. Here's the deal: In 1986, Kathy Sue Engle was kidnapped from the parking lot of an Oklahoma mall. Her body was found in a nearby oil field; she'd been raped and murdered.

Ervin, her daughter, was eight years old. Years went by without movement on the case, and Ervin grew up understandably consumed by the loss and mystery. It wasn't until 2009 that DNA evidence led investigators to a suspect who was currently incarcerated for another crime. He was convicted in 2011.

For folks like us — I mean Sarah and me, as well as all y'all loyal Best Evidence readers — all that is a fairly straightforward case, one that could probably be adequately covered from start to finish in a single episode of your garden variety anthology-style crime show. Who knows, maybe it was.

I mean, who can keep track of all those dead women in all those towns in the middle of the country? Who can track every single TV/streaming dance that begins with 80s-era photos of women with their kids, then cuts to a now-retired cop who recounts the case, then cuts to fake DNA lab footage, then ends with archived local news anchors reporting a cold case conviction? I can't, and that's my job.

That's why this inaugural book from poet and essayist Ervin feels like such a punch to the gut. As you read through her gracefully composed pages on her unmoored girlhood and growth past the age her own mother was when she was taken, we realize that her story is the story of every family from all those anthology episodes we turn on while we knit or fold laundry or run. Which we do, on a treadmill, because we are women and even things like running, outside, alone can be a dangerous and risky act. Like going to the mall can be.

That's not to say that Ervin in any way encourages mean world syndrome, because she doesn't — this is an individual, personal narrative, not a blanket statement about how the world is out to get you. At the same time, she has some remarkable insights about how gender-based crimes such as rape reflect on the value (or lack thereof) our society places on women, as well as the role we're seen as playing when we're attacked or killed. After all, the reason Sarah has a reason to ask me if shows pass my "treadmill test" is because the last thing I want is someone saying "I don't want to say she was asking for it, but...what was she thinking running outside, in the dark, when she could have just run on a treadmill at the gym?"

That casual type of dismissive, idle conversation about people who experience crimes is something that Ervin also takes a scalpel to. She leaves scars deep enough that phrases like "my favorite murder" or "this case was cool" are — one hopes — less likely to be uttered after reading. It's OK, I don't think she's trying to make us feel bad about ourselves. She's just trying to open our eyes.

Or maybe she's not. Maybe she doesn't give a shit about how we feel or think about things, and that's fine, too. The point is that the broad strokes of her story are those of a lot of survivors, and that's something that we all need to remember. And a book like this, with its elegance and weird, dark, beauty, offers that reminder very well.

Add a comment: