May 2024 Bonus Book Line-Up: Didion, Dunne, Watergate, Anarchy

the true crime that's worth your time

It's time for a book Line-Up! In case you're not familiar, throwing a bunch of properties in a Line-Up just means that we read the first 10 pages, or watch the first 10 minutes, of a bunch of things in a single medium, and give our recommendations based on that. It's not a perfect science, but it does help slenderize the to-do list. Uh, sometimes. (You can read another recent iteration here.)

Let's get to it with four books I've had on my TBR for a while…

After Henry, by Joan Didion

I ordered Didion's early-nineties essay collection after reviewing Money, Murder, and Dominick Dunne last week; I don't remember exactly why. That's a goodly stretch of my TBR shelves: I read a reference to it in another book or vintage article, the Brooklyn Public Library doesn't have it*, I hop onto eBay and order it, and when it finally shows up after the maximum amount of time suggested by the Media Mail window, I've forgotten what I wanted with it and it gets slung onto the "next-up" pile…which, thanks to this "system," is now multiple piles.

*it does in fact have After Henry; your local library system may have it as well

It doesn't really matter, since it's pretty hard to go wrong with Didion on the prose level. On the vibes level, different story. Didion's trademark gelid remove is often precisely the thing for true-crime accounts, particularly "major cases" – but at the same time, that sangfroid can have an unsettling effect. No subject seems to move or shake her, no matter how short the observational distance; "fiery," "tearful," et al. seem like concepts transmitted from deep space by one of the Voyager spacecraft. Didion was evidently comfortable with the perception of her as an éminence frais** and declined to apologize for it or reclassify it as a "diagnosis," which I admire, but the carapace of frost on her "I said what I said"-ness means there's only the one way to take "what she said." In other words, if Didion's (barely) fictionalized version of her brother-in-law seems like uncharitably sugar-free bigotry, that's surely what it is.

**not 100 on my French here; désolée

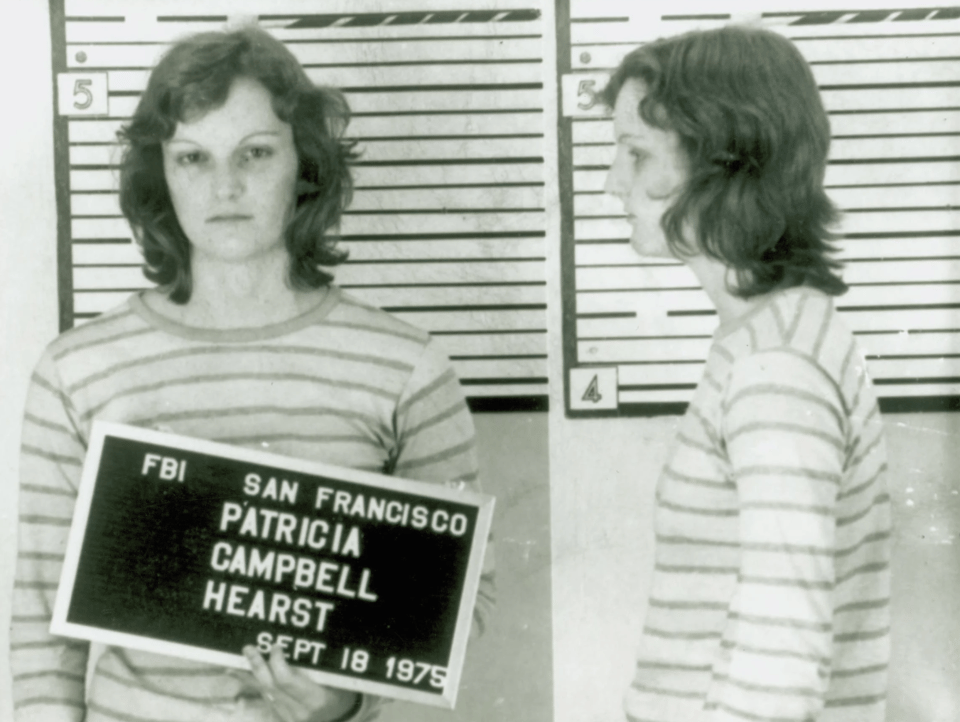

Still, the Didion stiletto usually cuts the right way for me, and the ten-ish pages I sampled here, a 1982 response to Patty Hearst's memoir – and to others' responses, to both the memoir and to Hearst's failure to perform perfect victimhood – is just right. I like a fuck-the-patriarchy fireball as much as anyone, but chilly shade on the topic has its uses too.

The book also includes essays on the Central Park attack and the Cotton Club murders; the former may not have aged so well, but I'll still READ IT and I recommend you do as well.

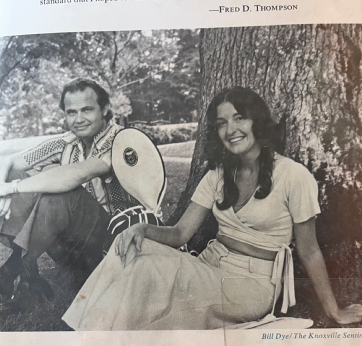

At That Point In Time: The Inside Story of the Senate Watergate Committee, by Fred S. Thompson

Yes, "that" Fred S. Thompson – who served as chief minority counsel to Senator Howard Baker (R-TN) during the legendary hearings. I didn't have much use for Thompson as a folksy conservative DA on Law & Order, much less as a momentary presidential candidate, but there aren't many Watergate memoirs I don't have use for, so if Thompson can write even part of his way out of a wet paper bag, this one's probably a lock…

…for me. I used to stock a lot of Watergate materials at Exhibit B.; after a couple of years, I stopped acquiring it, because it often sat, indefinitely. The approach of the 50th anniversary of Richard Nixon's resignation from office might light a fire under what's left, it just as well might not. At this point in the shop's life, Watergate inventory is pretty much always stopping at my TBR piles before it hits the shelves…may as well get something out it, right?

At That Point is going to have to wait just a bit longer before getting priced and listed, because I do think I'll keep going with it. The opening chapter is a little more focused on "underestimate my performative folksiness at your peril, elite sirs" story time than is ideal, and Thompson's recollection of his first meetings with several leading committee lights – "thank goodness you said that" this, "I think Such-and-So's afraid of you" that – reads like self-regarding spin, even if it really did happen like he says.

But it's got a bunch of pics interspersed with the chapters (none of which can touch the hem of the garments in that author photo, not for nothing), and the writing moves right along: introducing events and case figures, setting scenes, but not getting too painstaking for the case-heads in the audience.

If you're not a case-head, though, you can RESHELVE IT. (I'd like to say HOLD-LIST IT but the fact is, it's probably not in your library system, and it's not a cheap enough date for me to recommend buying it outright.)

Harp, by John Gregory Dunne

Like his wife, Dunne was an outstanding writer. Unlike his wife, Dunne's control of his own self-regard was variable. Didion's confidence in her own capabilities is understood; reading her isn't a cozy experience, but her work doesn't stand back from itself so that you can praise it.

Dunne's doesn't always do that, or it doesn't always do it to an off-putting degree. I liked both The Studio and Monster a lot, and while I could feel Dunne's pride in his own earth-scorching locutions in a few places, he had in fact earned it.

Harp, a tetchy collage of a memoir, is also a monument to midcentury Ivy-in-joke privilege that isn't as clever as Dunne thinks, and shot through with implications that Dunne will kick your ass if you don't kiss his. He reproduces hate mail he received about The Red White and Blue, and his (admittedly) "petty, small-minded and mean-spirited" response; he loftily mealy-mouths an excuse for not attending the trial of John Sweeney, who had killed his niece Dominique, but thinks wishing a prison rape and a subsequent case of AIDS on Sweeney balances that emotional ledger. Leafing through Harp, I kept thinking that we already have a Norman Mailer, and that the original was an inconsiderate dick-measurer naturally, versus seeming to seek out opportunities for proactive unkindness.

But this is what we could expect from a guy of Dunne's era and talents – not really interested in the feelings of others, not going to get checked on his bullshit thanks to his industry (and literal) stature – so here again with a Dunne-adjacent property, I'm not mad (or surprised), just disappointed. And on top of that, it barely qualifies in the genre. RESHELVE IT

The Infernal Machine: A True Story of Dynamite, Terror, and the Rise of the Modern Detective, by Steven Johnson

Given a qualified thumbs-up by the NYT earlier this month, Infernal Machine

is the story of two ideas, ideas that first took root in Europe before arriving on American soil at the end of the nineteenth century, where they locked into an existential struggle that lasted three decades. One idea was the radical vision of a society with no rules – and a new tactic of dynamite-driven terrorism deployed to advance that vision. The other idea – crime fighting as an information science – took longer to take shape[.]

from the book’s preface

If this sounds like an excuse on Johnson's part to dig into a bunch of sepia-toned process anecdotes about bomb construction; the legendary defusers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who didn't have many fingers left by the time they retired; and the irony of Alfred Nobel, of the eponymous Peace Prize, inventing dynamite, it probably is. But process, done right, is Buntnip – and that particular era in true/political crime is underrated, I'd say, or not appreciated for a barrage of lethality that lasted the better part of a generation. We remember the anarchists' "actions" as quaint, or slapstick; or we can only summon the wrongly accused (or over-punished, anyway) Sacco and Vanzetti when that time comes up. But Bill James notes in Popular Crime that, a dozen decades ago, the country was in serious danger of fracturing thanks to political fissures getting widened with TNT, and that for whatever reason we no longer understand that past threat as serious.

Not that that's sufficient reason to read this book, or any other on the subject; it's just interesting that the domestic-terror campaigns of yore are reducible in that way. As for Infernal Machine, I think I'll keep going with it; between Czar Alexander II's snotty benediction to future explosives-hurler Peter Kropotkin, a Teddy Roosevelt cameo, and an upcoming scene in which Emma Goldman reads J. Edgar Hoover for filth, there's enough here to keep me interested. I do think it's possible that the book is trying to force a framework into its chosen set of subjects, though, and/or that Johnson may have set his focus too wide, so let's go with a moderate HOLD-LIST IT – SDB

Thanks so much for subscribing to Best Evidence. Don't forget, Eve and I are discussing There Is No Ethan on an upcoming Docket episode, so you still have time to read along if you like. Got a Line-Up/review suggestion? editorial@bestevidence.fyi, or call/text us at 919 75 CRIME.

Add a comment: