March 2024 Bonus Review: BUtterfield 8

the true crime that's worth your time

[cw: sexual assault involving a child; death by suicide]

The crime

Trafficking and sexual assault of a minor, probably; extortion, allegedly; prosecutorial misconduct, very likely; murder, very possibly.

The story

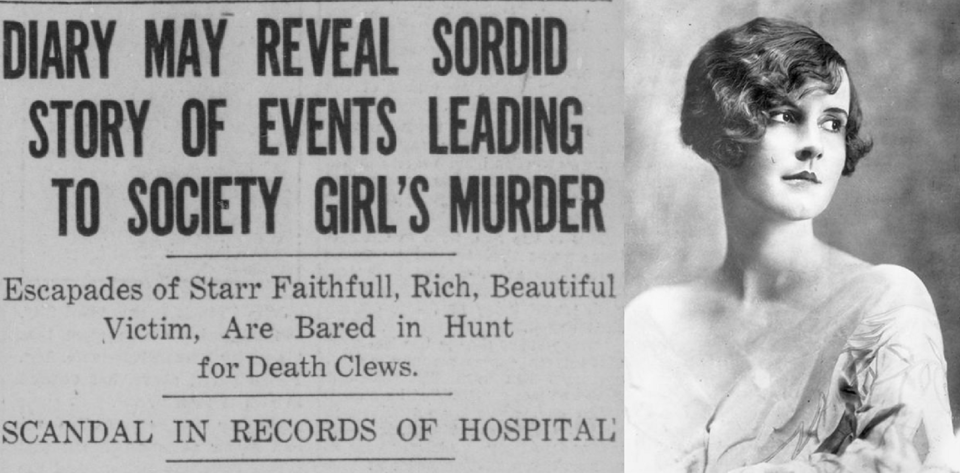

The drowning death of "American socialite and model" Starr Faithfull in June of 1931 may not in fact have been a murder, but it was surrounded in primetime-procedural motive – specifically, that, after many years of "erratic" behavior, Starr told her mother and stepfather that a cousin's husband, politician Andrew James Peters, had visited her at school and taken her on trips for the purpose of raping her when she was a tween. Confronted privately, Peters opted to pay the Faithfulls twenty grand, ostensibly for Starr's expenses pertaining to psychiatric care but probably so they'd zip it about the abuse; the hush money was intended as a one-time-only payment.

But Starr's stepfather, Stanley, was a hapless-inventor type who may have relied on frivolous lawsuits (or the threat of same) to make a real living, and allegedly kept coming back to Peters with his hand out and his brow suggestively furrowed…so, the story went, money Peters might have had to throw at a problem like the Faithfulls in the late twenties was no longer as ready to hand in the early thirties, and he elected to have said problem taken care of by other means.

As the investigation unspooled, the…imperfection of the Faithfull family's victimhood, I guess, made itself increasingly clear, followed by goodbye-world notes allegedly written by Starr that more strongly suggested she'd taken her own life. Stanley insisted powerful people had forged the notes, and later commentators (including dean of American true-crime compilers Jay Robert Nash) cited evidence-of-absence-type information "proving" Starr couldn't have suicided in the manner claimed by some theories. Authorities didn't declare either as the manner of death, and her demise remains unsolved.

I've mentioned Starr on Best Evidence before. The story of her downward spiral and untimely death, despite a whorl of ancillary complexities, is not necessarily as compelling per se as it is instructive about the kind of complex unsolved-mystery story that dominated the headlines of an earlier age – not to mention how unprepared the culture was to recognize "downstream" trauma, from childhood sexual abuse but also from the Great Depression itself, in a time when to discuss either money or plain old consenting sex out loud was Not Done. In some ways, it's obvious why the public latched onto Starr's mysterious death: the money/power of it all, but also the "we will, and can, never really know" space at its heart. Nearly a hundred years later, though, some of the reasons a citizen of 1931 might have latched onto Starr's tragedy aren't available to us. (Remember also that the kidnapping of rich people's kids was far more prevalent, and generally less deadly, than today. That the Lindberghs didn't lose hope for some weeks seems hopelessly naive to us now, but the original plan for Little Lindy probably really was to return him safely after the ransom hand-off.)

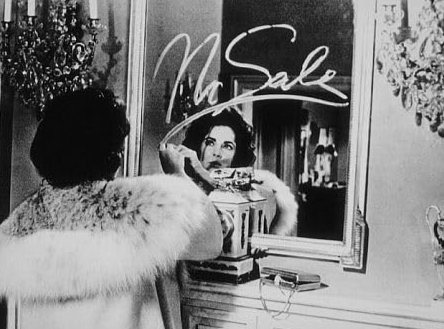

Anyway: the story never entirely went away thanks to John O'Hara's 1935 novel based on the larger case, BUtterfield 8 – and of course the 1960 film, based on the book, that scored Elizabeth Taylor a Best Actress Oscar, and yes, I've "finally" gotten to the actual subject of the review! Apologies for the delay! I took the long way not just because I don't have a ton to say about the film qua film, but because BUtterfield 8 itself has, and is constructed around, a handful of attitudes and givens that are almost illegibly remote to the 21st-century viewer. And those put the movie in an interesting conversation with the facts of the case, despite not really following those facts closely.

One of those givens is Elizabeth Taylor herself. There is another entire essay to be written about Taylor's Whole Deal and how it hasn't traveled especially well, but I'm not qualified to write it and you've got things to do, so I'll just say about her performance here that it's surprisingly compelling and nuanced, especially for her. Many of Taylor's performances don't work for me, relying on a movie-star persona and attendant meta gossip I don't understand or especially care about, and a style of acting I don't miss; her Gloria Wandrous (ostensibly the Starr character) is quite well done, and won me over.

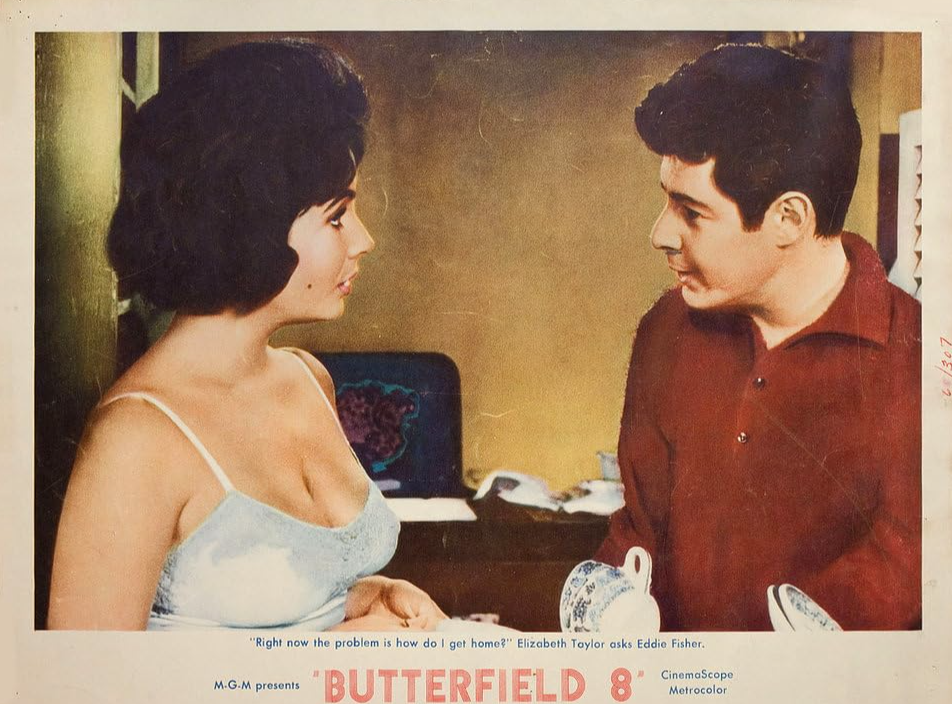

Granted, it had much too much time to do so, and other performances around her – chiefly Eddie Fisher, whom Taylor had bullied execs into casting thanks to that offscreen drama I mentioned – help hers look brilliant by comparison, but Taylor's also in the position of having to embody a character the Hays Code still wasn't comfortable drawing in multiple dimensions. I haven't read the book, but the film doesn't seem to know from scene to scene whether Gloria is a sex worker or what they used to call a "good-time girl," or some other "girlfriend experience" thing in between. The tone veers between tragic consideration of a fallen woman (who was trafficked by a boyfriend of her mother's back in the day) and snappy noir-ish dialogue about Gloria's unrepentant hussy-osity. I preferred the latter scenes, unsurprisingly, and the game-recognizes-game scenes between Taylor and Betty Field as Gloria's mother's bestie Franny really crackled.

But as much as you want BUtterfield 8 to send those two mismatched partners on a road trip, it's Eisenhower's America, so after what seems like a week of stagey negotiations in the broken marriage of Taylor's love interest, Liggett (Laurence Harvey, occasionally diverting despite an indecisive accent), and his wife Emily (Dina Merrill in a thankless part) – and only in film and TV do passive-aggressive richies shoot this much pointedly metaphorical skeet; just get a fuckin' divorce! – it's time to kill Gloria off before she can completely redeem herself with a straight job in a different town. And that's what the film does…not that it has the wherewithal to end after Dukes of Hazzard-ing Gloria's little convertible into a construction site.

Or to treat with the real anxieties underlying Starr Faithfull's stricken story and the adaptations of it: the reach, real and imagined, of the rich and powerful, when they want to hide their misdeeds; what happens when "survivors" don't; that somehow it's always the girl's fault, because it's easier to blame than help.

BUtterfield 8 is fine, but not worth seeking out if you haven't already – or paying for, at any rate; it's not currently streaming anywhere, but if it comes back onto TCM at some point, I don't know that I'd spend the 109 minutes. It's mostly notable for what it isn't saying and doing, for the window it opens into its own time and the time of the original crime, and as far as that goes, you're better off right-clicking some of the links in the Wikipedia entry. Morris Markey is probably a write-up of his own in this space, but his June 27, 1931 New Yorker piece about visiting the Faithfull family is worth a look if you subscribe. He gets a novella of sibling-relationship neurosis into a couple of strokes. (I also enjoyed the ad on a facing page for a residence hotel that later became a co-op, in which I lived for half a decade. "Complimentary maid service!") - SDB

Thanks for continuing to subscribe to Best Evidence! Got a suggestion for future bonus reviews? Email us at editorial@bestevidence.fyi, or call/text 919-75-CRIME.

Add a comment: