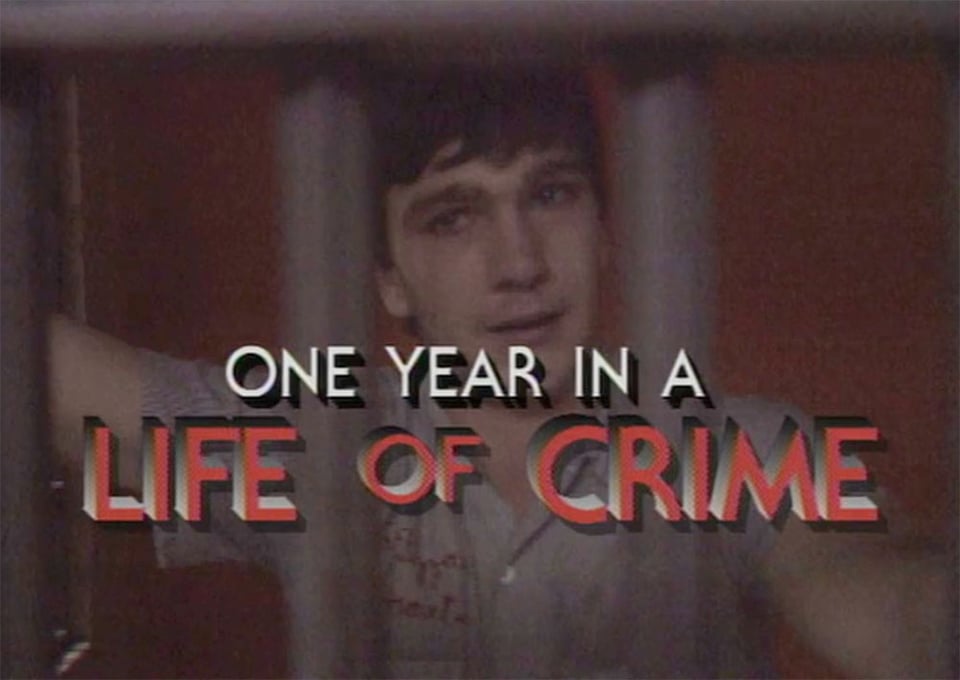

July 2025 Bonus: One Year In A Life Of Crime

the true crime that's worth your time

The first installment in what became a three-part, multi-decade project.

To read SDB’s review, subscribe now!

Want to read the full issue?

the true crime that's worth your time

The first installment in what became a three-part, multi-decade project.

To read SDB’s review, subscribe now!