The Last of Us Part II: An Exercise in Embodied Empathy

In adapting a video game for television, The Last of Us’s film-like narrative structure provides an easier starting point than most. Even so, HBO’s series took several welcome liberties in its first season, including two pre-apocalyptic cold opens reminiscent of showrunner Craig Zobel’s miniseries, Chernobyl, a critically lauded episode centering on the same-sex partnership between Bill (Nick Offerman) and Frank (Murray Bartlett), and a flashback focusing on Ellie’s mother (Ashley Johnson), providing a backstory for Ellie (Bella Ramsey)’s viral immunity. Such additions injected the show with an exciting raison d’ȇtre beyond the season’s rigid adherence to the video game’s original story beats.

Thus, a week before the second season aired, I decided to catch up on the video game that inspired it, The Last of Us Part II. As I progressed through the game over the next three weeks, I was vastly impressed with its sprawling, ambitious scale and intimate, complex, morally grey characterization facilitated by the player's limited but powerful interaction with the story. I am confident that showrunners Zobel and Neil Druckmann will deliver a perfectly satisfying entry in splitting their adaptation of this game into two seasons. However, so much of what the video game accomplishes through its use of embodied empathy is inevitably lost when translated into a purely visual medium. [Spoilers for The Last of Us Part II follow]

Most notably, the game requires the player to control two opposing characters: Ellie and Abby. Because the scripted narrative ultimately takes priority, the player cannot make many individual choices to affect the story as they would in an RPG. Instead, the player must come to understand and wrestle with these characters’ psychological tics, motivations, and decisions as they navigate from level to level. This creates a wealth of tension as the player progresses through Ellie and Abby’s journeys, especially when their paths cross at a few key moments.

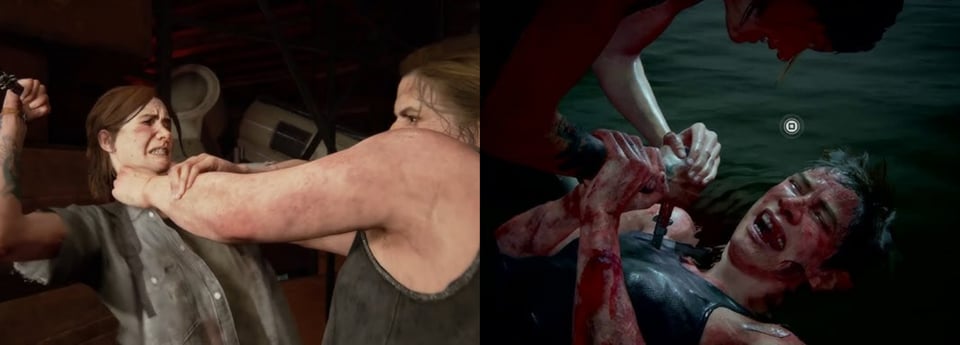

For example, after playing through three days in Seattle as one character and then the other, the two engage in a climactic confrontation in which the player, as Abby, must take down Ellie. Stealthy cat-and-mouse sections are punctuated with moments of tense quick-time events. In one especially unsettling instance, the player must follow an onscreen button prompt to choke Ellie. The motion-captured expressions of fear and desperation make this experience excruciating, exacerbated by the victim of this violence being not only a beloved character, but one whose role the player has spent several hours fulfilling and sympathizing with. Until now, such scripted executions only appeared when engaging with non-playable characters. Reversing that dynamic here creates a powerfully disorienting effect, placing the player in an emotionally compromising position until a third character eventually appears and ends the fight.

Later, under more drastic circumstances, the two cross paths again, with the player taking control of Ellie this time. Both characters are physically weak, wounded, starving, dirty, bloody, and psychologically harrowed. The player cannot avoid the fight, or even sit back and watch passively. Every slow, painful punch, dodge, and struggle requires full active participation, controller in hand. Ashley Johnson and Laura Bailey’s motion-captured performances as Ellie and Abby bring an uncomfortably grounded, tragic layer to the already brutal situation, forcing the player to look in the faces of the lives which the game compels them to destroy. Again, the violence mercifully stops short of fatality. However, that tension lingers long enough for the player to reckon with their attachment to Ellie and Abby as characters and everything they’ve lost.

Beyond these cutscene-heavy fights, similar mechanics also pervade core gameplay sections, where the player sneaks around or engages in combat with infected creatures and armed human enemies. Patrol guards call each other by name, cry out in anguish when they discover their friends’ dead bodies or witness the player blow their heads off, and beg for mercy if the player knocks their weapon out of their hand and they’re the last one standing. The decision to humanize and individualize enemies like this creates an interesting personal dynamic, giving additional motivation to avoid conflict apart from simply conserving ammo and health items. You, the player, must decide if a person needs to die, even when the stakes aren’t nearly as consequential to the story.

As fascinating as these details are, I won’t pretend that the game’s execution is always perfect. Outside of the incredibly effective Abby and Ellie fights, cutscenes punctuated with quick-time events make little difference other than to remind the player that they are playing a video game. In this sense, Ellie’s encounters with Abby’s friends would be much easier to translate to television and retain their thematic purpose within the story. The player can also simply plow through and kill everything and everyone in sight with no remorse, despite the development team's efforts to make that path less desirable than in the first game. Those patrol guards do intend to kill the player if they find them, after all. Yet, the approach we get demonstrates how well interactive media can elicit a powerful emotional reaction in the player. Naughty Dog pushes their budget and the PS4 to their graphical limits, making each encounter as immersive as possible, short of wearing a VR headset. It’s worthwhile to take such participation in gory, high-fidelity violence in a more personally affecting direction and bring the player’s attention to that fact.