Agnès Varda: Nouvelle Vague Vanguard

2025 marks 70 years since Agnes Varda pioneered the French New Wave. I decided to binge her entire filmography.

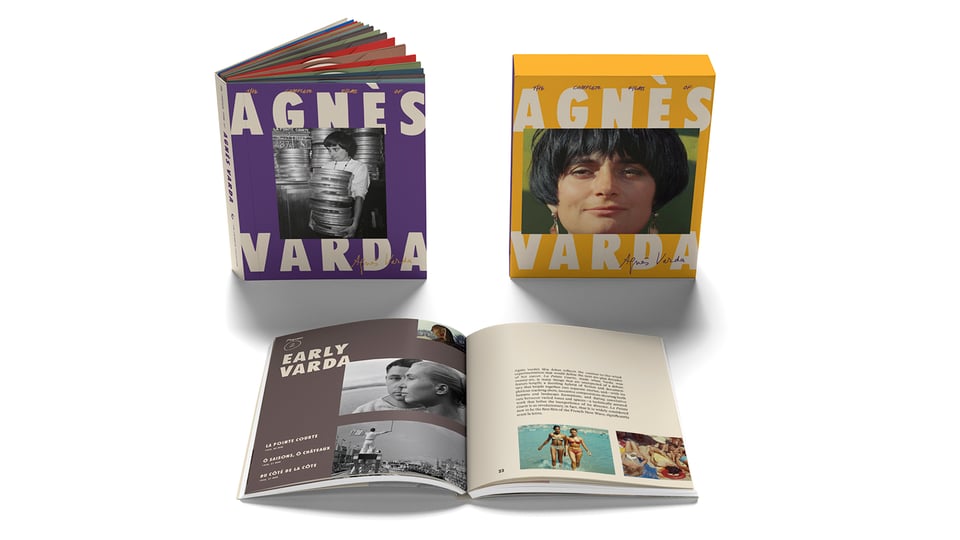

Cleo from 5 to 7, my favorite French New Wave film, is currently out of print. You can still stream it through HBO Max, The Criterion Channel, or Kanopy. However, to truly own it, without worrying about licensing rights expiring, the only option is to purchase the Criterion Collection’s “The Complete Films of Agnès Varda” box set. So, when my grandmother asked me what I wanted for my birthday last year, I directed her to Barnes and Noble during a half-off sale, applied my reward points, and got twenty feature-length films, eighteen short films, a five-part docuseries, and an overwhelming amount of additional material, including a book of essays and program notes, all for $125.

I’m sure with a thorough internet search, one could pirate every single second of that, but it feels good to hold the collection in my hands. It feels worthwhile to devote my undivided time and attention to every film, going through one of the fifteen discs each night. Taking the time to explore Varda’s whole body of work filled me with a deeper appreciation for her as an artist and a human being, more so than if I had only ever watched “the essentials.”

I want to begin by illustrating why Cleo from 5 to 7 means enough to me to warrant purchasing the director’s entire filmography. Firstly, “Sans Toi” remains one of the most staggering musical sequences I’ve ever witnessed, accomplishing immense emotional power with a simple slow camera zoom. The black curtain behind Cleo (Corrine Marchand) completely transforms the space as the song reaches its climax, with a swelling orchestra joining Michel Legrand’s diegetic piano to match the turmoil in Cleo’s head. The film also manages to paint a sprawling, vivid portrait of the Paris Left Bank, a central hub of the French New Wave, more so than any other film in the movement. A taxi radio dispatches updates on the Algerian War; Cleo visits a sculptor posing nude for students in her art studio, and a projectionist who showcases a short silent film-within-a-film featuring fellow New Wave darlings, Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina. It captures a particular time and place so impeccably in merely an hour and a half.

I also gained a greater appreciation for another favorite, Vagabond. Taking the cold, dirty, naturalistic landscapes for granted, I never noticed how masterfully she composed those establishing shots. Behind-the-scenes interviews also brought to my attention a running motif, in which the protagonist, Mona, walks from right to left across 12 sequences throughout the film, the camera stopping on an object that mirrors the next recurring sequence. Joanna Bruzdowicz’s modular chamber score over these scenes chilled me much deeper on a second viewing, as well. Mona’s fate is doomed from the very beginning of the film, leaving no hope or mystery. That fatalism manifests itself immaculately through the music; abrasive, uncompromising, just like Mona, and just like the film’s narrative.

Beyond revisiting these masterpieces, this venture allowed me to explore Varda’s lesser-known short films. I was already familiar with her phenomenal documentary on the Black Panthers. Narrated in English, Varda depicts the politics, culture, and motivations behind a Free Huey rally in Oakland, California, fairly and without judgment. She allows her subjects to speak for themselves and summarizes their points with an admirable matter-of-factness. The short films that were new to me, mostly documentaries, range from quaint to middle-of-the-road. However, one standout I'd like to highlight is the dense, tightly-paced Uncle Yanco. Freewheeling and brimming with charm and whimsy that would later characterize her 21st-century work, Varda blends an exploration of her family history through reconnection with a distant relative from the Greek side of her family with the psychedelic, bohemian spirit of late-60s San Francisco. Those vigorous nineteen minutes left me breathless.

That being said, Varda’s oeuvre is not without its missteps. Critically panned at the time of release and reappraised by very few, if any, The Creatures exhibits a cold cynicism that betrays the humanist demeanor of her most celebrated works. And despite my delight with One Hundred and One Nights’ numerous historic film references and inside jokes, that enjoyment never went beyond surface level. It stands simply as a celebration of a century since the invention of the motion picture, not intended to be taken too seriously, nor should it. Nonetheless, I’m glad I gave them a fair chance, even if I would not have sought them out on my own otherwise.

Lastly, I wish to recognize the most emotionally devastating section of this illustrious program: the disc focusing on Varda's late husband and fellow filmmaker, Jacques Demy. After an HIV/AIDS diagnosis, but before he passed away, Varda filmed the gorgeous, moving docu-biopic hybrid, Jacquot de Nantes. A depiction of Demy’s childhood, interspersed with relevant clips from his musicals and home footage of an older Demy filmed concurrently with the dramatized scenes, the film came across as fairly standard. The making-of featurette, “Agnès Tells a Sad and Happy Story,” finally brought the waterworks. By Varda's account, Demy succumbed to his illness after wrapping and never got to see the finished product. Varda describes editing the footage she shot of her husband on the beach through tears streaming down her face. I cannot fathom the struggle of working with the last surviving images of one's spouse of nearly thirty years, tasking oneself with creating a definitive document of their life and work in the immediate aftermath of their death.

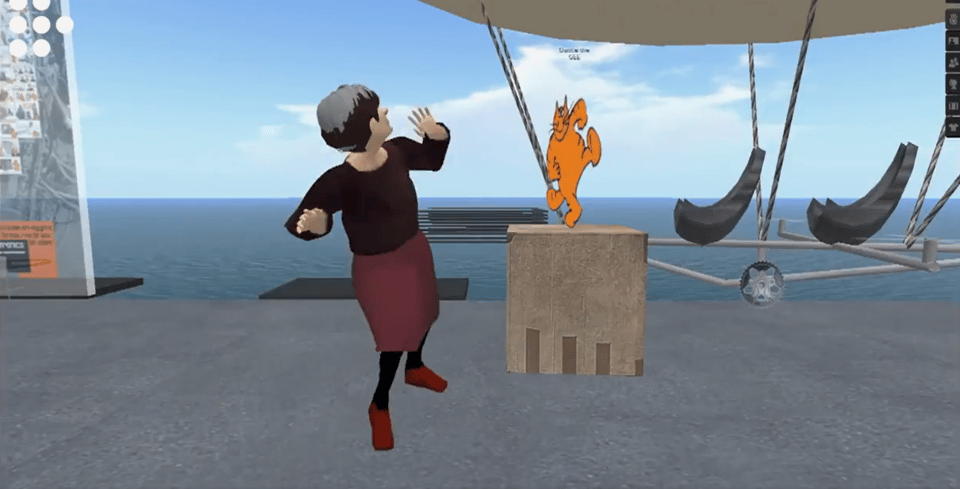

That heartbreak is compounded tenfold, having lost Varda to cancer in 2019. Even so, what a force of nature! To pioneer a new mode of thought in filmmaking with her 1955 debut feature, La Pointe Courte, seventy years ago, and to live long enough to create an avatar in the virtual world of Second Life and have it dance defies comprehension. Varda was a formidable and vivacious presence behind and on camera. She left behind an enviable legacy and enjoyed heaps of well-deserved praise during her lifetime and beyond. She certainly doesn’t need yet another person to champion her work. Even so, I allowed my curiosity about her films and their historical context to consume my days for a month straight, and I would have gladly spent another month or longer doing more of the same. Viva Varda and the avant-garde spirit she stood for.