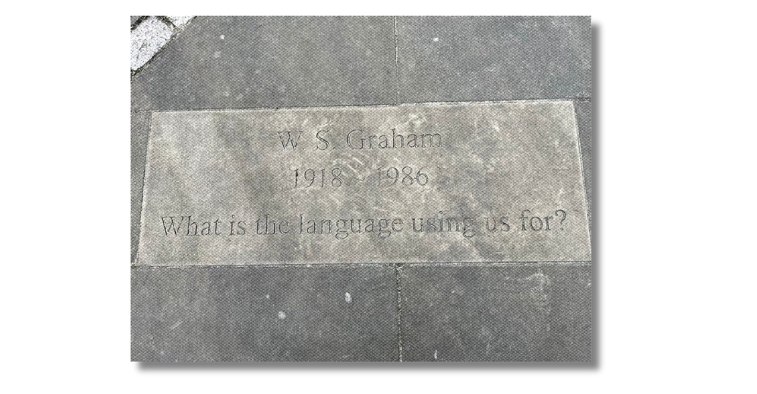

What is the Language Using Us for?

Holly Herdon and Mat Dryhurst's AI art and how it make u think

WE WELCOME VISIONS OF NEW FORMS. SUBMIT YOURSELF TO SOMETHING MORE.

You walk through the automatic doors and step from Hyde Park into a space which better resembles a church than an art gallery: exposed brick, the chanting of a choir in some unseen chamber further in, and a gilded altar piece directly in front of your eyes. The altar is gold and grand, uncanny in how brand-new and unweathered it looks to the eyes of someone forced to step inside every bloody chapel, cathedral, and Christian antechamber on a two-week trip to Italy. Far from simulating the tranquillity of those spaces, this altar is making a fucking racket.

Unlike the 100% haunted houses of worship crouching in wait behind every corner in Venice, this altar houses a fleet of GPUs and their accompanying whirring fans. Those fans are being put to use playing the “hymns” produced by the artists Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst. The rest of the Serpentine’s North Gallery, currently displaying their installation “The Call,” is arranged in a similar fashion, the collision of the divine and historical with the sacriciously modern. There are further “liturgical objects,” either symbolic of or sometimes literally housing modern tech. And then there’s the singing.

It gets weirder as you move through the space. On one side of the circuit which orbits the chambers in the centre of the gallery, the singing is unmistakably human. Herndon and Dryhurst travelled the country, collecting recordings of choirs both amateur and professional. That’s what you’re hearing down the right hand side after passing by the altar at the entrance. Carry on, and there’s a shift. I had a lot of fun trying to identify the exact moment this British Hymns Megamix was replaced, instead, with the “singing” of a proprietary artificial intelligence the artists fed with those recordings. The words being sung are no longer Latin or Olde Englishe, but gobbledigook. The voices are not those of a group singing together, but the simulation of such, with equal parts eerie slickness and messy with digital artefacts.

A second sacrilege: bringing AI into the art gallery. A reputable art gallery, anyway. AI is bad! Yes, broadly, I agree. Foremost amongst the reasons for the pushback in this horrible new era of machine learning has been the implications for those in creative careers. While not unfounded, it’s clear the wielding of AI as a tool by, say, film and TV studios, or marketing agencies, or whichever boogeyman you want to (justifiably) point the finger at, is simply the next step in the commodification of creative work by non-creatives that’s been going on for yonks. Algorithms and trend-hopping and lowest common denominator and disrespect for artists has been part-and-parcel of industrialising for art as long as there’s been a concept of “industry.”

The environmental concerns are, if I’m honest, more unfounded. The use of AI constitues but a small slither of the damage all computer usage amounts to (so think about that when you spend two hours on TikTok before bed, me). Then there’s the undeniable fact that “creative output” of these large language models (the ones that absorb and spit out derivative text) and generative artificial intelligence (the crummy image and video generators that give people freakish elbow-fingers and four boobs) are uniformly shitty. Low effort, mid reward content that can fill platforms, whether social media or television or movie screen.

Herndon and Dryhurst pass muster with ease on the financial-moral level. Built into “The Call” is an “R&D project running in parallel to the exhibition” with the choirs involved “to establish a legal and governance framework that enables the creators of datasets to collectivise their rights to gain greater agency over their data when it is used to make AI models.”

One of the most common mistakes when slamming generative AI to generative AI people is to leave out the humanity. AI critics talk about creative work as a metaphysical, elusive thing; the call of the muse, the ineffability of inspiration. This is, annoyingly, sort of accurate — but it’s not the whole story, right? Being creative is work. There is labour involved, skills to develop, craft to learn. If you believe making art is beyond your ken, because the collective unconscious or cosmos or whatever hasn’t communed with you, then you end up with the other side of the coin which is: people behaving like robots anyway. This is one of the taboos “The Call” is prodding at.

And what about the aesthetics? It’s easy to detach “The Call” from our conception of AI artworks because, as discussed above, it’s not shitty looking. All the imagery, still and moving, produced by generative models so far has looked abjectly awful. And not only that, but it all looks the same. Even those early attempts to recreate the art styles of famous painters to make a load of Shrek portraits bend towards the same samey, airbrushed-3D model look. AI work is immediately identifiable, it’s non-existent fingerprints obvious to anyone who has eyes to look.

AI plays a part in the existing cultural enshittifcation as much as anything, a flattening and smoothing of aesthetics. Those weird animations of cutesy animals, of celebrities snogging, that fill boomer’s Facebook timelines and the faces of their poor suffering children and grandchildren. They’re nothing more than background noise, except they take up your full attention.

I went to see Herndon and Dryrhurst’s piece, The Call, before Christmas (it runs at the Serpentine until the start of next month). I had reason to think about it again upon the publication of Mood Machine, Liz Pelly’s timely polemic against Spotify. It’s a properly bracing account not only of the company’s brazen ripping off of artists, so well-documented it’s now accepted with a shrug of “no ethical consumption under capitalism,” but also its deadening effect on music culture beyond this financial/material devastation. “Having captured a massive user base and facing pressure to actually make money,” Nicholas Quah writes in his review of the book, “Spotify no longer worries about its quality as it tries to suck as much marrow from the user’s bones as possible.”

The Spotify villain arc has followed the rulebook of artist exploitation to a tee. Offering opportunity/exposure through the leveraging of exciting new technologies, withholding the rewards, and then trying to do away with the artists altogether so they needn’t share even the meagre slither of pie they’d initially been offering to them. Spotify dominates not only music, but podcasts and, increasingly, audiobooks as well. CEO Daniel Ek has said that that the company’s “only competitor is silence.”

This means, in a free market race-to-the-bottom, Spotify doesn’t care what you’re listening to, just so long as you’re listening. Why wouldn’t it encourage people to upload sped-up “remixes” of copyrighted material popular on social media, or ten hours of white noise, or AI-generated songs? Why wouldn’t it produce that AI-generated music itself, circumventing that whole nasty “royalty paying” business altogether?

“The suggestion that the businesses of pop music, mood-enhancing background sounds, and independent art-making ought to all live on the same platform, under the same economic arrangements, and the same tools of engagement, is a recipe for everything being flattened out into one ceaseless chill-out stream,” Pelly writes. Spotify puts forth a concept of music not as a surprising, inspiring, often strange art that can soothe, provoke and challenge, but as, per Quah, a “means for passive mood regulation.”

Innumerable artists have taken that to heart and flooded that platform, and many others, with anhedoniac background soundtracks which twist Brian Eno’s discrete compositions into something more intentionally bland. Elevator muzak we willingly put on. “It’s mindfulness vs. mindlessness,” writes musician Phil Elverum, “and humans are losing bad.” Music becomes an easily-ignorable phenomena, each track indistinguishable from the next, as those AI videos and pictures flooding social media.

The hack fraud sitcom directors the Russo Brothers struck a considerably more techno-utopian note when they spoke publicly on their own predictions for AI. They imagined a solipsistic future where films could be “generated” according to your specific interests and tastes, even putting each individual viewer into the action. The tech to pull this off is likely a ways away — right now it sounds as sophisticated as those naff, personalised picture books you can buy for kids — and fundamentally misunderstands the forces driving the widespread adoption and money-making AI suggests.

Like Spotify recommendations or Amazon’s “suggested items” or the Netflix algorithm, it’s not about tailoring their output to your taste. It’s about pushing the content they want you to consume. It’s as sophisticated as the old marketing categories which group people according to income/race/gender. Rather than highly-specific customised art-worlds for all, you have a choice of maybe three. As the Murakami totebag has it: If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Were someone to ask (and, to be clear, to date nobody has) I’d politically align myself as Marxist-anarchist. That means I am annoying on two fronts. I’ll primarily view things through terms of economic oppression, and then shrug about our ability to do anything about that within our current system. Such cynicism in one so young can sometimes have the strangely contradictory effect of making you see things through the oppressor’s POV. Horseshoe theory truthers, log off now: I don’t mean that. I mean that if you understand the world to be a nightmare of avarice, it can be easy to assume the worst of intentions, to lash out with cruelty and pessimism. Or better yet, absolve yourself of responsibility. If you know how AI is being primarily used by individuals and organisations — let alone the state! — it’s easy to see it as a net negative and to leave them to it.

Let’s take it a step further. I could make the argument that the world wide web as a whole is inherently evil, having been initially funded and developed in part by the American military. This is a rhetoric tool called “hyperbole” and I use it all the time, because it’s funny. In actuality I am keenly aware of the gentle, radical, even utopian potential use of the internet — why, it’s how I’m communicating with you, right now! — and of both the ability to be and “locations” online which circumvent the data-mining, highly mediated, doomscrolling hellscape of its lithosphere. Federated servers, homemade websites, the republic of newsletters: all of these, nominally, use the tool of the web for something other than its primary profit-making use.

There is the possibility that interesting people could make interesting things with AI. Some already are! There are legitimate concerns, as I say, around machine learning. They’ll probably come to pass. It’s a mistake to shrug and consider ourselves powerless, however; to find the tech too complicated to comprehend, or to imagine a postapocalyptic future out of Terminator, rather than an advancement of the dreary boring dystopia we currently occupy. Gaining as good an understanding of this emerging thing as The Enemy.

Bearing all that in mind, I cannot deny I had a lot of fun with “The Call.” I wandered around it like a wide-eyed, sugar-tweaking child. I thought it was brilliant. I kept grinning and opening my mouth wide the way paid actors do in adverts where they pretend to be on a thrilling Jet2 holiday. The most fun I had was with “The Oratory,” a curtained-off space in the middle of the gallery where only small groups were permitted to enter at a time. At the centre of all the White Lodge drapery is an altar, featuring one of the faux-religious reliefs that illustrate the installation as a whole. In front of it is a white microphone. You lean into the mic, and make a noise. The Choral Diffusion model, as Herndon and Dryhurst have christened their AI, will harmonise.

It’s so fucking weird. It’s so fucking fun! It captures something of the experience of mucking about with an echo in a space with suitable acoustics, with the naive joy of using a computer tool for something it wasn’t intended: making the text to speech on the computer in your grandparent’s basement robotically recite rap lyrics or, in a more modern example, having the TikTok voice narrate scenes from American Psycho. All of this play made possible because of the artist’s radical use of emerging technology — as well as, crucially, the reassurance offered by the disclaimer by the entrance: PLEASE NOT THE VOICES OF VISITORS ARE NOT RECORDED. It was a singularly strange, disquieting, off-putting and inviting, unreproducible experience. It was art!

Subscribe to a sitting ovation