I got it from the computer

Three novels of the internet

A regular customer at work asked if I’d read No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood. It’s the next pick for her bookclub; I enthused that it’s an accurate reflection of what being on the internet is like. She screwed up her face, not unfairly, for that is the experience of being online: extremely begrudging, happens anyway. I do stand by the statement as the principal strength of the book, Lockwood’s first sustained work of “fiction.” There is a sense of allegiance, if not a sense of proprietary, with her — someone who was regularly tweeting and tweeting in a similar way at the same time I was, albeit in my case to much lesser effect and a much smaller audience.

To both be inside the “portal,” as her autofictional narrator calls it in the book, and to retain the ability to write about it with clarity and direct knowledge, is quite a feat. And it’s funny, too! Drawn directly from Lockwood’s own experiences — of being Very Online, until a tragic family incident fairly wrenched her from the timeline into the present, where the irony-poisoned observations of online brush uncomfortably against the sensitives of real human feelings — the only narrative contrivance proper in No One Is Talking About Us is the bisection of real life and online.

In the first half of the novel, Lockwood’s narrator discovers the portal encourages as much as it stymies connection. Her online persona makes it easy to identify fellow sufferers of the highly meme-literate lost in the sauce of what level of irony they’re working on. The implied intimacy, a shared secret, can also make for fraught interactions. It is strange to bring the online behaviour, humour, and language into meatspace. Data points build a person. The second half of No One Is Talking About This makes the counter-argument: a person is made up not of millions of little bytes, but cells.

The sudden, tragic moment breaks something in the narrator. A glowstick snapped that illuminates the darkness. In the final section of the book, she tries to return to the portal but, unable to engage with the apocalyptic and narcissistic discourse in the same manner, having experienced such mainlined reality, she backs out again “without a sound.” While Lockwood is too smart to invoke the hateful, Catholic concept of grace achieved by dint of suffering, the idea that one can be removed so immediately and permanently from online to offline world by a big enough incident — and that, in doing so, one is immediately reconnected with the essential forces of the “real” which underpin human existence — feels too tidy por moi. You put down your phone, and suddenly you’re given access to the truth of existence, just like that? That’s all it takes? Bliss in ignorance, after being deluged with information for a lifetime?

Readers and critics alike lose it when someone acknowledges the existence of the internet in print. They do things like dub a school of writers “alt-lit” for a particularly internet-y tendency to be distant and disaffected. They say things like “her writing isn’t just about the internet, but born of it: a reflection of an age where the line between online and off was rubbed out a long time ago.” They do this despite the fact they are often mostly writing and reading on the internet themselves. It seems somehow taboo, to combine the disposable trash of content with the sacrosanct printed word (let’s not think about the amount of books published a year vs what sells and is read vs what is pulped, remaindered, purely for shelf decoration).

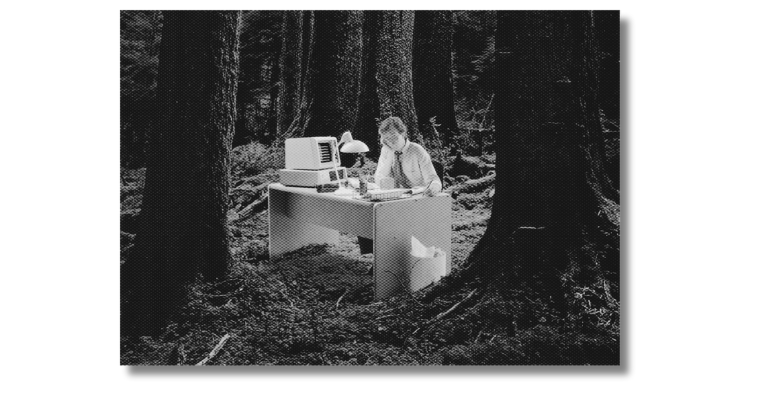

This is reflective of many of our understandings of the internet versus real life: one is good, the other is bad. And also, they are distinct, discrete experiences. This is not a brag — how could it be? — but time was, I would occasionally get recognised off of the internet. I was spotted in bus stations and at indie gigs and outside bars by strangers who would address me by my internet handle. It freaked me out. It really did feel like a transgression, a breaking of the omerta of that era of online, which was halfway between LiveJournal semi-anonymity and the no-shame posting-your-Ls TikTokers of today. My online and offline personas shared plenty in common, but maintaining a clear separation seemed important.

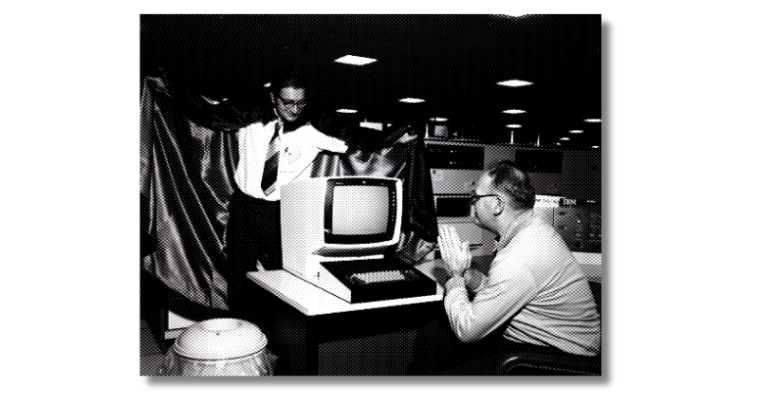

Go back to the advent of the internet novel, as we know it today, and the Lockwood dichotomy is flipped: freedom is in having access to everything all the time, not shirking it. Before we were burdened by speedy WiFi and information overload, we had to make do with the dial-up modems, text-based interfaces and accordingly dense genre of cyberpunk. Neuromancer, William Gibson’s ur-text of the “movement,” is packed to the smacked-up dolphin gills with what became the genre’s hallmarks: multinational corporations which act like nation states, a hardboiled detective plot and cast transplanted from post-war US to the streets of an imagined Tokyo lousy with neon, and a population oppressed ever further by each new technological innovation seized upon by end-of-history capitalism.

Since we’re smart, and live in the present, and not a fool, who lives in the past, we can read Neuromancer and chuckle at what Gibson got wrong: in our boring dystopia, we remain in thrall to shitty VR headsets, social media, and failed tech businessmen running the federal government, but we don’t get lightsaber-katanas or wraparound shades or sex. Most anachronous is the idea that “knowledge is power,” and that the internet would afford untapped reserves of knowledge for those with the gumption and know-how to grab it.

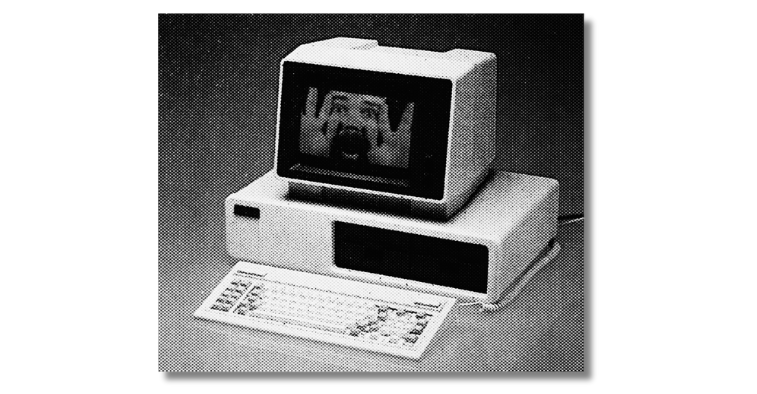

Gibson’s protagonist, Harry Case, is so good at hacking that an enemy had his central nervous system fried. People were scared of him in cyberspace; he could take what you had without you knowing. The only way to get at him was in meatspace. The book’s online world is a visual conception of the internet, common for the era and the texts it influenced, from Snow Crash to The Matrix. It’s a paraphysical space one “enters” using a virtual avatar, albeit with “real” connections between your body and a complicated fictional technology. Through a plot so needlessly complex it can only be a Chandler homage, Case makes contact with the eponymous figure, a souped-up artificial intelligence which lives online and could either herald the end or transcendence of human consciousness.

Neuromancer makes the case for the internet not as a trap that seduces and destroys when willingly sprung, but something that can be both understood and controlled. It can then be leveraged at will. An individual who has complete mastery of the internet has similar mastery over the world; they are one and the same.

Insisting that the internet is not “real life” is a powerful and useful analgesic when, say, journalists are overstating the influence of their tweets (or lamenting that their words, in fact, appear to be powerless); when one is hounded into a locked account due to an regrettably popular prompt or bad opinion; when you keep bumping into an ex on your suggested follows and need a break, to “touch grass.” Yet it’s a fallacy, for many of us, similar to denying the power of the free market. The internet is obviously not the be-all and end-all of human existence, yet as long as those in power insist on its influence, it has it.

Gibson’s conclusions are as pat as Lockwood’s. The answers to everything aren’t to be found on a hard drive, just as they cannot be found by refuting the smartphone screen, as if they’re a blurry magic eye picture that simply requires your full attention to bring them into focus. The internet is and is not real life. It offers freedom and oppression. You cannot really escape it, and do you even want to?

[Spooky Tony Blair voice] There is a third way. The narrator of Lauren Oyler’s debut novel Fake Accounts is credibly unsure about this whole internet business while, as is the style of the time, presenting a facade of confident understanding of the internet and its discontents. The hook is that the lead character, a side-step from Oyler’s own online writing persona in a similar move to Lockwood, is dating a studiously offline man called Felix. He professes to have no social media presence and is ignorant of the trending topics, irritating terminology, and detached-scold affect of the 21st century web.

That’s until the narrator discovers, while pawing through his phone as he sleeps, that Felix in fact presides over a popular Instagram account trading in right-wing conspiracy theories. She is both surprised and vindicated in her suspicions. She carries on as normal, with this bomb in her pocket, and plans to break up with Felix at some undetermined near-future date. He beats her to the punch by dying while she’s at the women's march heralded by Trump’s inauguration. Yes, it’s another bisected narrative! In the second half of Fake Accounts, the action moves from New York to Berlin, where the narrator and Felix first met, and where she feels an impulsive desire to move, her boyfriend’s sudden demise providing the jolt necessary to upturn her online commentariat life.

In Berlin she feels the freedom to reinvent herself, over and over, through dating apps. She goes for drinks with a dozen men, cycling through a pre-planned persona at each, distinct from one another and with her “true” self. It’s a very online tendency, and one borrowed from the presumed-dead Felix — that you can be an entirely different person depending on the audience you address, and none is necessarily more or less legitimate from the other. It’s also, y’know, what the spies and crooks of the genre fiction that inspired Neuromancer’s convoluted plot machinations do.

Oyler’s narrator does not move between online and offline spaces, because there is no clear distinction to be made between those spheres, or in how we act in each. Deception is possible in both, yet it requires an equal and opposite level of self-deception on the person being deceived. How do your elders fall for obviously fake news items shared through Facebook than wanting their preconceptions confirmed? Why would you be drawn to a conspiracy theorist Instagram account unless you already had the feeling something was wrong? Why would men go on dates with an obvious fabulist unless they thought there was a chance they’d get laid regardless? Fake Accounts is all about the way the internet affects people, and vice versa. It’s about the fact that the internet is so vast and so pliable to manipulation by bad actors that it is essentially unknowable — but that’s been true of people in the many centuries prior to gaining access to finstas. Pretending to be someone you’re not has a long, rich history.

While both writer and character are knowingly arch, the book is not a nihilistic embrace of this fact, just an acknowledgement of it. Gibson and Lockwood, comparatively, offer only a partial understanding of things. Each is aspirational in its own way; Neuromancer posits that a little guy can wield information against an otherwise all-powerful corporation (and/or nation), that the internet offers real ultimate power, and it’s possible to become what the AI refers to as “the sum total of the works, the whole show.” The internet as liberatory space.

The dream offered by No One Is Talking About This that it’s even possible to become fully offline. That it cannot be bent to your needs, it’s totally compromised, you gotta just go monk mode. The narrator of Fake Accounts can neither flee the internet, nor the ghost of her newly dead boyfriend. In Berlin she’s assailed by memories of Felix, even while she’s set adrift on her online dating odyssey. At the book’s climax, a friend contacts her online, with a cache of online articles, to reveal that Felix in fact faked his death as some sort of art prank. Oyler’s novel knows it’s a lie to say you can completely know the world and its people. This is a cynicism gleaned from the internet and its culture. It’s also true.

The internet doesn’t have all the information. People can be similarly selective with what information they shared about themselves, and their selves, IRL. You can only ever have an incomplete understanding of people, and the world, even if you can hack and access the hidden information locked behind firewalls. Felix returns at the end regardless of the narrator looking for him. There is no differentiation between online and offline. Much of life is chaos beyond our control. This is not necessarily a sad thing, just more honest. Fake Accounts is neither capitulation nor surrender but an accurate reflection of where we stand. The only real choice is: what are you going to do with that information when you get it?