Eve Babitz's Front Pages

A combative history of Eve Babitz, in images; or, why Lili Anolik's Didion & Babitz ain't no good

I used to be an artist, now I’m a piece of ass

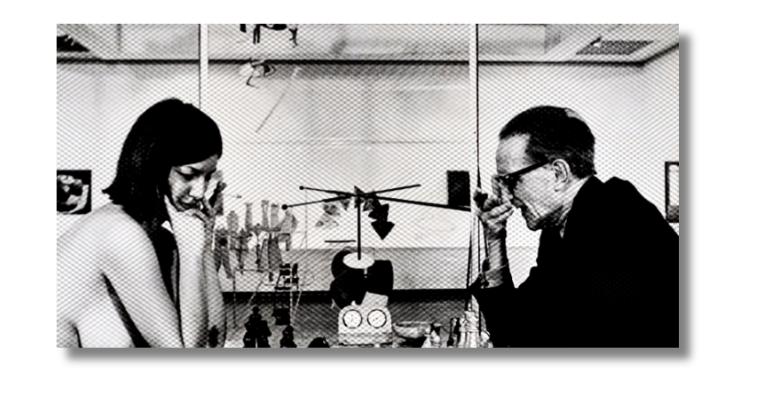

Eve Babitz is a writer known best for three images. There’s the black-and-white portrait on the cover of most every edition of Eve’s Hollywood, with Babitz properly glam in feather boa and black bikini. The later-in-life paparazzi shots, following reports she had been badly burned after dropping a lit fag onto a gauze skirt, the imagined-then-confirmed counterpoint to that early bombshell image. Finally there’s the earliest, taken when she was just 20: a nude Babitz playing chess against a significantly older, significantly more clothed Marcel Duchamp.

In the autumn of 1963, Eve Babitz was just beginning to think of herself as a writer and artist; she was having an affair with the gallerist Walter Hopps. These facts are not unrelated. Her biographer, Lili Anolik, wrote that “passing herself off as a groupie allowed Eve to infiltrate, edge into territory from which she'd otherwise have been barred.”

This early attempt hadn’t quite come off. Hopps had convinced Duchamp — who had long since “retired” from art to dedicate himself to chess — into a retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum. Babitz could not attend the private opening because Hopps’s wife was unexpectedly in town. She had to plump for the public opening, which took place a couple of nights later. To pile humiliation upon ossa, her sister Mirandi had wangled her way into the private opening — as the date of one Jan Wasser.

The opportunistic Wasser, “a Time photographer who drove around with a police radio in his car,” stuck around for that second evening. Duchamp and Hopps, too, playing chess on a raised platform in the middle of the gallery. Having failed to seduce Eve, Wasser proposed a photoshoot modelled on the scene unfolding on that platform, with Babitz on the other side of the board in Hopps’ place. Naked. A sort-of homage to the artist’s “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” and, in the grand tradition of naked portraiture, a last-ditch effort to get a beautiful young woman to take all her clothes off.

“Of course, me being the nude sort of made me feel like I was pretending I was way bolder than I really was,” Babitz later reflected. “But then, anything seemed possible — for art, that night.” She arrived back at the museum early the next morning. She was nervous. She was cold. She had already decided “that if I could ever wreak any havoc in [Hopps’s] life I would.” She was committed. Everything had been set up. Duchamp arrived; Wasser gave the signal; Babitz dropped her smock.

The photoshoot served not only as revenge against Hopps. It was also her first artistic act. It granted Babitz a smidge more access to a creative life. Afterwards she began working more seriously on writing, and especially collage, with artwork appearing in Rolling Stone and as the cover of Buffalo Springfield’s second album. She celebrated this coming out with a banner in her apartment: I USED TO BE A PIECE OF ASS, NOW I’M AN ARTIST. Anolik notes that it was simultaneously an exhibitionistic and private act, aimed at an audience of one. Hopps soon got back in touch.

The image reached a more significant audience, and then some — often without Babitz being credited. She reflected on this paradoxical omnipresence/anonymity, in a wonderful and equivocal piece written decades later for Esquire: “the photograph began showing up on things like posters for the Museum of Modern Art[…]I just wasn’t sure I wanted to be identified. Maybe it would be better to be ‘and friend.’” In most of the shots Wasser took that morning, Babitz’s face was visible. In a rare moment of chivalry, he granted her final say. The photo so widely replicated is the one she chose, where her dark bob covers her face.

Eve Babitz is a writer best known for not being Joan Didion. Rarely is she spoken of without reference to the éminence grise of the personal essay, of the Franklin Avenue scene in LA which Babitz also inhabited. It does not go both ways. Didion is a cultural icon unto herself. There has been significant attempt to redress this imbalance in recent years, beginning with Anolik’s biography, Hollywood’s Eve, and continuing with a reissuing of the Babitz back catalogue by the New York Review of Books, and subsequent embrace of Eve by her seeming inheritors: Jia Tolentino, Lena Dunham, et al.

Even these reappraisals feel the need to applaud Babitz for the ways she wasn’t Didion. Eve was gossipy and fun where Joan was arch and distant. Eve was euphemistically “voluptuous “ where Joan was a small, unimposing woman. Eve was prone to mess and prolix where Joan was spare and specific. Eve was a celebrated slut while Joan was a sexless intellect. These and other rote juxtapositions reach their zenith in Anolik’s recent Didion & Babitz, a disappointing extension of a really rather good Vanity Fair article and an unnecessary retread of her previous biography of Babitz, Hollywood’s Eve.

The new book attempts to argue for a closer association between the writers; a personal one, something real, rather than simply as two cultural symbols between which exists a productive friction. What Anolik discovers is that there really wasn’t that much interaction. She therefore resorts to spinning her wheels.

She muses over the possibility that John Gregory Dunne, Didion’s husband, had the hots for Eve; elsewhere she reports speculation that he was gay, so, make of that what you will. She presents unrelated anecdotes from interviewees keen to straighten records outside the scope of the story. She expends a lot of the wordcount wringing her hands about publicly coming down as “Team Eve,” redressing that imbalance by smirkingly pointing out every spelling mistake she uncovers in Babitz’s private correspondence.

The most tangible collaboration between Babitz and the Didion-Dunnes was the latter’s boosting of her early work, to the point that they were onboard semi-officially as early editors of Eve’s Hollywood. Babitz recognised both the cultural capital of this leg up, and of rejecting it. By 1973 she was going around parties bragging that she “fired Joan.” The lengthy dedications in Eve’s Hollywood, published the following year, includes a shout-out to “the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who I’m not.”

It was Babitz who created her public persona contra to Didion’s. It was such a successful exercise in personal branding it persists to this day. Didion is just as responsible for no small amount of her own mythology. The introduction to Slouching Towards Bethlehem sees her extolling the virtues of being “so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive” in pursuit of her fly-on-the-wall reportage. She does not, notably, form her legend with derisive comparison to Babitz.

Anolik all but admits to the flimsiness of Didion & Babitz’s premise in the book’s foreword. “I’m calling what they had a ‘friendship’ because I need to trap their dynamic in language,” she explains in a typically overwritten run-on sentence, before at last acknowledging: “it was both more than a friendship and less.” In fairness to her, part of Babitz’s charm in later life (otherwise endangered by a right-wing crankism her increased solitude incubated) was her maintenance of her persona, of which the rivalry was part and parcel.

“Lili, you did it, you killed Joan Didion. I’m so happy somebody killed her at last and it didn’t have to be me,” she giggled with ghoulish glee upon publication of an earlier piece Anolik wrote on Didion for Vanity Fair. In it she describes Didion as, at best, a disingenuous ingenuine and, at worst, a “angel of death” heralding California culture’s destruction. With her new book you could say, with a similar position of tongue-in-relation-to-cheek, then Anolik is killing Eve.

Jan Wasser went on to photograph many cultural icons following the Babitz-Duchamp portrait. Amongst them was Didion: the iconic images, taken around the publication of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, of the writer in the California combo of dress-sandals-ciggie, posing alongside her pure white Corvette Stingray. The image is used on the 4th Estate reissue of The White Album. The rest of Didion reissues — of both her fiction and memoir — use photos of the author herself, broadly contemporaneous to when the books were written; Babitz’s appearance on the jacket of Play It As It Lays is the exception.

Didion & Babitz works best when the subjects speak for themselves. They are invariably more interesting, fighty — and willing to provide enough rope with which to hang themselves with, without Anolik’s help. When Anolik “asked Wasser if he’d instructed Joan on how to dress or where to stand during their session, he replied, tone reverent, ‘With a girl like Joan Didion, you just don’t tell her what to do.’ When I asked him why he’d chosen Eve for the Duchamp photo, he replied, this one contemptuous, ‘She was a piece of ass.’”

Eve Babitz is a writer best known for being less than Joan Didion. How else to interpret the use of the Babitz-Duchamp photo on the most recent reissue of Play It As It Lays? Not the most famous one, mind you, but an outtake: one where Babitz’s face, masked and anonymous on the one she selected for public consumption, is clearly visible. A final triumph of Didion, artist, against Babitz, piece of ass.

Play It As It Lays is the story of one young woman’s descent into nervous breakdown amidst Hollywood excess, of coke dissociation and passionless sex. It is not Joan’s story. The suicide pact that ends the book came from a anecdote she told at a party. Didion’s own breakdown, meanwhile, was explicated in the title essay of her 1979 collection The White Album, induced by her strained relationship with Dunne rather than a strung-out party lifestyle.

The armchair Jungian has it that Babitz was Didion’s Shadow Self, the one who actually lived out all the stuff Joan observed, imagined, wrote about. To slap Babitz on the cover of Play It As It Lays is to associate her with the protagonist, whose unchecked hedonism and lack of self-preservation destroys her life.

Is this what Babitz is reduced to, between the use of the photo and the more “balanced” retelling of her dynamic with Didion — transmuted from artist back to a piece of ass? In Anolik’s own words, “a symbol rather than an individual, an exploitable sex object”?

4th Estate’s reissues were published in 2017, when Didion was still alive. A friend points out that Joan herself could well have signed off on their covers. There’s no real way of finding out whether this is true, nor of discovering the intentions of whichever member of the art department decided upon the Duchamp outtake. Fun though baseless speculation is between friends, it’s of no use to us here. What we do know for sure is that it’s not the first time the photo from that session has been used for a book cover.

In the nineties Babitz fielded a call from an editor putting together a book on Duchamp and the West Coast, asking if she could use the photo. Babitz fretted; “‘You’re not going to use it on the cover, are you?’ But when I found out the cover photo was to be of Marcel alone, I felt insulted. Mixed emotions hound me after nearly thirty years of mixed emotions. I want to be on the cover, immortal, but I don’t want anyone knowing it’s me. Except my friends and people who like it.”

Eve Babitz is known for three images. The paparazzi photos were beyond her control, and without her consent. The cover of Eve’s Hollywood was staged, in part, by her; for better or worse, it’s how she’s remembered by many, a mask of persona seared into the flesh-and-blood face of a person. The Duchamp photo, taken somewhat on her terms, has long since slipped her leash, hidden face revealed. Eve Babitz is a writer who was always being sold out.

Aye up! A while ago you subscribed to a sitting ovation on Substack, a highly irregular newsletter by Tom Baker. I’ve revived it this year, on a less Nazi-friendly platform, with a renewed focus and schedule. Every fortnight I’ll send out an essay, usually about books, below 2,000 words. I hope you’ll stick around. Cheers me dears.