Artefact 234

Strategic design with systemic sensibilities?

I usually remember to mark 4th May somehow, because it is one of our official birthdays. I resigned on that date twelve years ago to start Smithery, and of course not long afterwards made the first Artefact Cards for some client workshops.

Twelve years. It's not just the longest job I've had, it's nearly longer than all my other previous jobs put together.

TL;DR - it's reflection time.

For the past nine years, since an epic blogging stint unpacking our purpose, method and more, we've referred to Smithery as a Strategic Design Unit.

It's now time to revisit what that might mean in 2023, which will inevitably mean more writing, thinking and exploring over the summer.

All of which will feature here at some point I'm sure, but this newsletter is the opening of those rabbit holes; lots of questions, collections of links, emerging into some... better questions, at the very least.

First though, a brief practical detour...

The Artefact Shop: 2023 EURO-FRIENDLY edition

Artefact Cards was a side-project that found a life of its own, and became a little place for forging our own tools. Luckily, we've never had to rely on it as a main income generator. Which is fortunate, because the pandemic put paid to in-person workshops for a while, and Brexit has been a particularly unpleasant event for anyone running a small business that ships things to Europe. Red tape, customs issues, useless webinars by ill-prepared government departments, startlingly-pricey delivery companies... the list goes on.

It's almost like the backers of Brexit hadn't thought it through at all. In the words of Logan Roy...

HOWEVER... over the last few months, we've been piecing together a new infrastructure behind the Artefact Shop, remaking the site itself, and most crucially of all, thinking about who and what it's for.

The shop will be a home for experimental products, collaborations with friends, and culture probes to explore ideas. Rather than just the core ranges, expect to see more interesting things for sale in small batches in the coming months.

Most importantly, thanks to a new service out of Finland (thanks EAS Project), European shipping is much more affordable, and back to being super convenient e.g. you won't have to collect it from your local post office, or pay global delivery firms more than the value of the items you've bought.

It'd be nice if the world wasn't this hard, but it is.

Context isn't everything, but it is everything else

Trying to peel apart all the systems around something purportedly simple like 'making something in the UK and selling it online' is a useful challenge in itself, because again I feel exposed to another reality I may not have otherwise seen. Revealing and revelling in the unseen has become second nature in a way.

Smithery was initially positioned as an Innovation Studio, based on my previous 'Chief Innovation Officer' role. But those first three years taught me one key lesson; it doesn't matter how good an innovative piece of work is in isolation, there can always be something that derails it. You may well know the kind of thing...

"The boss loves it, but says we've not got the budget to launch this yet"

"We can't progress until the engineering team has capacity"

"We heard there might be another team in the US working on this, we should wait and see what they do..."

You hear these sorts of things often enough, and you realise the more important part of the practice is to not just work on the thing, but to attend to the context in which they emerge. Where might you have mapped out these other considerations in advance to smooth the passage of work?

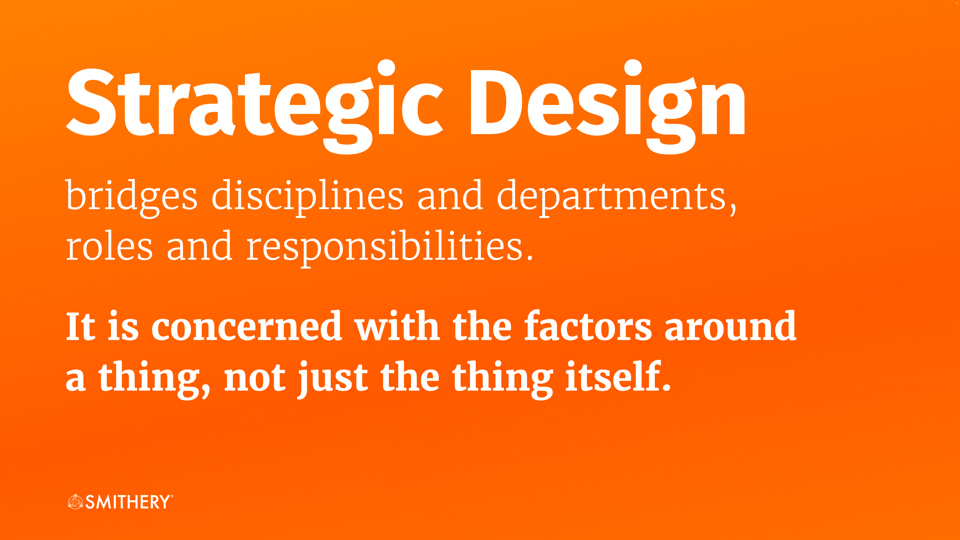

Crucially, it was in reading Dan Hill's 2012 book, Dark Matter and Trojan Horses; A Strategic Design Vocabulary, that I realised there might be a useful term emerging, Strategic Design, to describe what we were beginning to learn. We shaped the following definition for the Smithery slide deck around that, and by and large it has stuck since:

It has always been a useful explanatory piece that would fit with the studio tagline of Making Things People Want > Making People Want Things.

So why reappraise this now?

'Don't bore the client with the map'

Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino and I were talking back in early Spring. As part of her recent work at the Design Council, she was investigating the difference (if there really was much of one) between Strategic Design and Systemic Design. I talked a little about the definition above, and we shared perspectives on different angles and articulations of the general kind of work each term implied.

At some point, we started discussing the bridge from Systems Thinking to Design, the tendency amongst some to start drawing an ever-more complete and faithful map of the system... which brought to mind the 1:1 scale map from Lewis Carroll's Sylvie & Bruno:

‘What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?”

“About six inches to the mile.”

“Only six inches!” exclaimed Mein Herr. “We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!”

“Have you used it much?” I enquired.

“It has never been spread out, yet,” said Mein Herr: “the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.”

The thing I remember most about the conversation, as we unpicked the mapping process and its place in systemic design, was a spontaneous moment of reflection - "don't bore the client with the map". I have been thinking about this a lot since, and why it resonates in particular.

In part, it's a reminder for me to fight my own tendency to map, model and explain a collection of dynamics visually, and then dwell on them too long. It's part and parcel of having a background in economics, perhaps, as it's the bridge from 'assumptions to conclusions', as Jonathan Schiefer points out:

But more significantly, this reflection is being driven by looking at approaches like Gigamapping, which is a particular subdomain of where 'systems meets design'.

I look at some of these maps and think 'where and who this is actually useful for?', and the answer always seems to be 'the people who did the mapping'.

Mapping as a verb is really useful; it is a doing thing. You and the team get to hold and shift many layers of complex information around, and spot new opportunities. As Dr Roser Pujadas puts it, “Mapping is a social practice of sensemaking that shifts from individual cognition to shared understanding”.

Unless your client is part of the mapping process, maybe we should always question whether they need to see it at all?

Over time, practitioners become more attuned to the sorts of things that you may want to look for once a map starts to emerge (which brings us into the territory of abductive reasoning, but that's a whole other newsletter).

You will tend to know where to look, and where to act.

Perhaps I would argue that if we want to identify a key difference, Strategic Design has a bias for action, and Systemic Design a bias for exploration.

Let my explain it another way.

Rob Poynton once taught me a workshop game called Colour and Advance. You line up a group of ten or so people, who have to improvise a story. The rest of the room are going to give them one of two instructions; 'colour', or 'advance'.

The first person starts, and makes up the first line – "I set out for a walk from my cottage" – and the room will typically ask for 'colour'.

"It's a small cottage with a lovely garden".

"Colour!"

"I've lived there for many years"

"Colour!"

"I always try to start my day with a walk, as it's set in lovely..."

And so on.

It's only once the crowd asks to 'advance' that it moves on to the next person in line – "But this morning, I found there was a stranger standing just outside my gate..." – and the story starts to go somewhere.

Perhaps if Systemic Design is colour, and really describes all of the factors around where complex problems exist, Strategic Design is about choosing the point of intervention, and what you do next.

Which is hard of course, because everything is changing all the time...

Alive and dynamic

One of the problems with maps as a static noun, rather than mapping as an active verb, is that the world changes underneath your feet, and you need to be alive to it. This guest post for the Design Council, 'Ways of designing: A reflection on strategic and systemic design' by Bernd Herbert and Mani I, brings this into focus a little.

I mostly agreed with their exploration on first reading, but struggled a bit with this interpretation:

"Strategic design is what we do, and systemic design is a way we can do it".

At first, I disagreed. I'm not sure Systemic Design is a way, certainly not in the traditional design method of using the term. But maybe it depends on how we want to interpret the idea of a way.

If we're talking about a way in the Bruce Lee sense it could work, as in Jeet Kune Do, or the 'Way of the Intercepting Fist':

Lee stated his concept does not add more and more things on top of each other to form a system, but rather selects the best thereof... Lee considered traditional form-based martial arts that only practiced pre-arranged patterns, forms and techniques to be restrictive and at worst, ineffective in dealing with chaotic self-defense situations. Lee believed that real combat was alive and dynamic.

For me, this chimes with some of the things you pick up around Systemic Design, like this from Design Journeys Through Complex Systems by Peter Jones & Kristen Van Ael:

And key for me from the passage above is this "The toolkit provides a full stack of powerful resources for systems change that can be learned and adapted into a personal repertoire".

These are things to experiment with, pull apart, reconstitute as a mix with other things, and evolve as you go. Everything as LEGO, to be pulled apart and remade according to context, but never becoming a burden for your process that you always have to lug-around. In fact, you could easily paraphrase Bruce Lee's own statement about Jeet Kune Do for Systemic Design...

"Again let me remind you [SYSTEMIC DESIGN] is just a name used, a boat to get one across, and once across it is to be discarded and not to be carried on one's back."

Fixed maps and static models aren't what we need now.

Learning to let go

It can be hard to lean into that idea, especially if you feel you've invested a lot of time and effort into the initial creation.

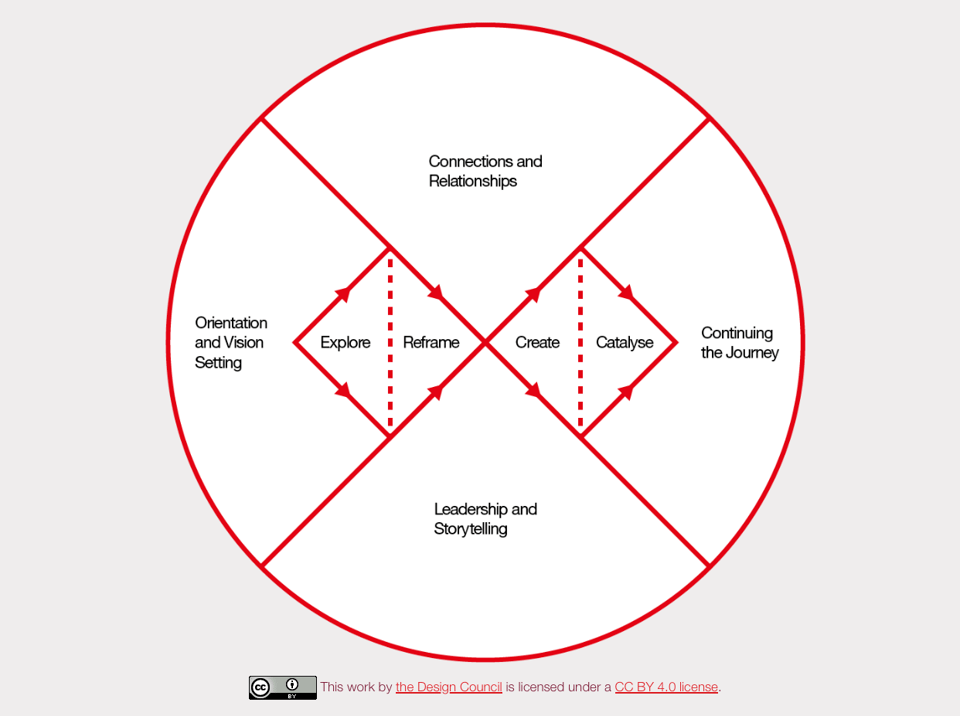

The Design Council had launched their Systemic Design Framework back in 2021, which is definitely a worthwhile upgrade for the Double Diamond itself, and I remembered I wrote a little about it at the time too.

I still think a lot of the ideas and language makes sense, and broadens out the territory adeptly to get anyone involved around design considering the things they must in 2023.

The other week though, I sat in a workshop being run by Alastair Somerville, on behalf of the Design Council, taking some of the concepts within it to explore how it becomes a repeatable set of tools for designers and clients to explore this space.

During these discussions, I realised that beyond the obvious need for the Double Diamond as a Design Council brand to remain a part of it, I don't understand why the diagram looks the way it does.

For instance, is this telling me Connections and Relationships are not a part of the Explore section? For me, it's a bit like all of the right notes are there, but just not necessarily in the right order.

Credit to the Design Council for bringing different voices into the debate to reflect on where the model has come from, and what future it might have.

This piece from their former Director of Design and Innovation, Richard Eisermann, is well worth your time:

"The question is whether the Double Diamond is still, given the tremendous changes in design practice over the last two decades, fit for purpose? The answer: probably not. The ascendance of fast-paced digital design, along with the complexities of the challenges designers are currently addressing with services and systems, have left the Double Diamond a bit short of breath."

And last week's live event, with a panel discussing 20 years of the Double Diamond (recording should be available soon) featured some interesting points.

The most relevant for me was Tim Brown of IDEO describing the original model as 'a heuristic, not a method'. For him, it was a great way to get design involved more strategically in a way it wasn't back then.

Perhaps, to hark back to the Bruce Lee idea, maybe the double diamond is the boat that has brought design across, and now needs to be discarded as a leading tool for a growing practice.

What is more interesting for me is where something like the Double Diamond (as a heuristic, not a method) could be introduced across different parts of education curriculum in a way that broadens it from being a capital-D Design Tool, to being a small-d design approach for many, many more people.

After all, as more and more people bump against design at some point in their working life, it makes sense that they shouldn't have to have to have chosen to study it specifically early on in life.

Future lines of enquiry...

Well, this feels long enough for now, certainly, but I have a desk full of related notes and ideas to explore further. Over to you, perhaps - what's most interesting for the next edition of Artefacts? Some possibilities...

a) What is a designer anyway?

Given all the above, and with an ever-broadening scope in the world, we don't really have the time to get territorial about who is and isn't a designer, do we?

For instance, Joana Choukeir's recent piece on A new age for life-centric design education makes that fairly clear...

"Design is all around us, and most of us have an active role in it even if we may not recognise that. Whatever industry we work in, we all design mindsets, practices, products, services, infrastructure and policy that shape our world in some way; now and for the generations to come, regeneratively or degeneratively, whether intentionally or not."

On the other side of that line, you have an existing group of capital-D designers properly contemplating the burdens and expectations as they look to the future. As Manuel Lima points out in the opening to his recent book The New Designer, "The reach of design has never been greater. While this is a positive accomplishment for a discipline eager for recognition, it also brings an acute layer of responsibility."

There's definitely something in here I'd like to explore more, especially as someone who's never been comfortable calling himself a Designer, Strategist, Futurist, Economist etc etc... and yet will happily play in the gaps inbetween all of these spaces (Keller Easterling's Medium Design - How to Work on the World is a good book for you if you feel the same, I think)

b) Is regenerative to unsustainable as antifragile is to fragile?

Why does all this matter, anyway?

I was at the RCA's "Design in the 21st Century" event last month – I am occasionally invited in as a visiting lecturer – and was struck that the conversation has definitely moved on from when I was first invited there some eight years ago. The conversations the panelists were having made me want to return to the idea of Leastmodernism I spoke about there in 2018:

"How do we fuse together than spirit of modernism, the wide-scale, far-reaching transformation of the world, but centred around the idea that it’s about what you’ve not done, what you’ve chosen to leave out, the repairs you enable… what are the repeatable patterns and expectations we can build into a wide variety or products, services and systems so that the expectation of less becomes a habit?"

As the panel continued, I took some more notes around what sort of system design needed to exists in. Deciding upon the absence of something is as much design as shaping its presence, perhaps? For every brief, should there be an anti-brief? And if in doing nothing, how might you still create circumstances in which a customer is happy, a client is satisfied, a planet benefits, and a designer still gets rewarded?

Looking back at my final note, I wonder if this is pushing me to understand (for the first time) the deeper context in which people are using the word Regenerative in terms of design.

I wondered if this was part of a triad as Taleb would have described it in Antifragile:

Whereas Taleb's key triad is Fragile–Robust–Antifragile, perhaps the appropriate triad for design is Unsustainable–Sustainable–Regenerative?

And if so, what might we take as lessons from that thinking?

If you've any thoughts on which you'd like to hear about next, or links / books you think I should look at, please just email back and say hello.

Signing off, shaping the future...

That's it for this edition, with one exception. Simon White asked me to do an interview for his Masters in Systems Thinking in Practice, which we did yesterday. It made me think a lot, and discover things I didn't know I was thinking about.

And given what I said earlier about letting go of things, I'm now wondering if it's time to move on from Making Things People Want > Making People Want Things as an organising idea.

The last nine months or so have seen us working on a fantastic United Nations Development Programme project (more on that another day), and it just feels like wherever we could, we should be working on the hardest things we can. Let's see where this goes.