The Comfort of History

In times of crises, what comfort can we find in the past?

by Abby Roberts

I meant to write this newsletter much sooner, in time to promote my essay on nationalist myth-making in Middle-earth, which was published in Speculative Insight in April. You can still read the essay. It’s free and I think it’s pretty good. Bret Devereaux, historian and blogger known for A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, called it an absolute banger, a high I’m going to be chasing for a while.

But despite several false starts, I couldn’t write this newsletter until late June. As I observed last newsletter, the times have been shit, and I can’t write when I feel like shit.

I envy authors who can write through their pain, turning it into something meaningful. I have never been able to do that. I create best when I feel safe and content and far enough from my feelings that I can take them out of me and hold them glittering in the palm of my hand. But for me, the dark feelings—grief, despair, anger—are like a black hole, a sticky morass that I teeter on the edge of. If I get too close, I’ll fall in, and I know—from experience—that it will take me a long time to extract myself. When I’m in the trenches, I’m only capable of creating art that shows views of the trenches from within, and that’s not the type of art I wanted to create. I barely wrote a word during the first Trump administration.

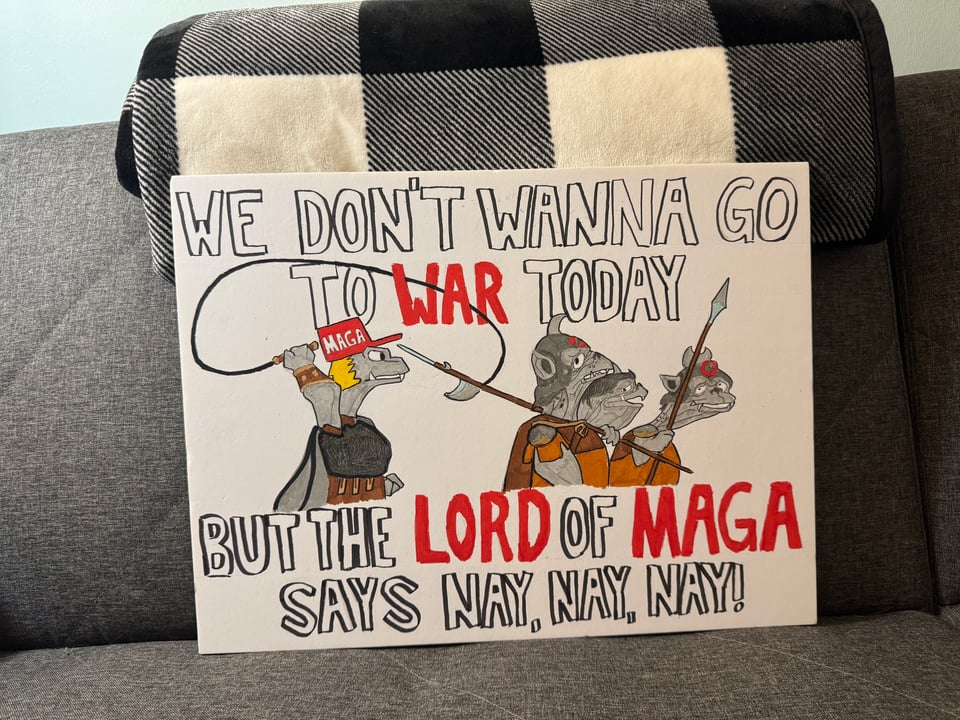

I’ve been doing other things. I’ve been politically active. I participated in my local No Kings protest on the 14th. It helped. It was catharsis and a show of force. It reminded me that more people are against that asshole than with him. I’m really proud of the sign I made:

But I’m not even a part-time activist. Partly due to talents and temperament lying in other directions and partly due to the time and energy demands of activism added to those of my full-time job. I think activism and civic engagement are important, all the time, not only during crises. Protests show Those Assholes that not all of us will acquiesce to the administration bombing Iran and kidnapping people off the street and eroding our personal and political freedoms. Protests also temporarily relieve my guilt and anger and the persistent voice in my head that urges me to do something. But protests drain my energy, and being on edge all the time drains my energy, and I need to do something to refill that well so that I can respond to crises as they arise. You cannot live on rage alone. Rage burns bright but it flares out and leaves you spent.

So, in March and April, I dabbled in historic fashion. I’m sewing a ring pouch, a type of bag that Anglo-Saxon women hung from their belts because their clothes didn’t have pockets sewn into them. I have a partially hemmed veil and fabric to make a dress. Specifically, I’m planning to make something like the blue dress, worn by the personification of virtue on the top right, in the 11th-century Bamberg Apocalypse.

I have sewn small projects but never made clothing before. But it doesn’t have to be couture, it just has to be fun.

I’ve also been teaching myself to drop spin, a method of twisting fiber into yarn using a handheld spindle. For thousands of years, until the advent of the spinning wheel, the task of drop spinning united most women in agricultural societies worldwide, regardless of class, language, or culture, as they needed to spend almost every free moment of their time spinning to produce enough thread to clothe their households. (The abovementioned Bret Devereaux discusses spinning as part of textile production here. See also Virginia E. Postrel’s The Fabric of Civilization for an accessible introduction to past and present textile production.) Fortunately, I don’t need to clothe myself and Violet with the thread I spin, but having something to do with my hands helps evict the squirrels from the attic that is my brain.

In May, I attended Westmoot, which was great fun, and I wish I had had the presence of mind to write a newsletter on that. On my return, I replayed Pentiment, an excellent game, somehow bombing the persuasion check worse than I did the first time. And I started reading the Chronicles of Brother Cadfael, enjoying them despite my historical nitpicking. While I’ve done little sustained writing (drafting, editing, rewriting), I’ve thrown myself into researching a historical/fantasy/comedy project set in 9th-century Ireland, which I refer to by the working title Monk WIP. In short, I’ve taken refuge in history, or at least in historical fiction.

My interest in medieval history started in high school when a desire to write better Lord of the Rings fan fiction inspired me to start learning about the real middle ages. I started college in 2015, so as my naive young adult self worked through the political and personal upheaval of the first Trump administration, she also took classes in Arthurian literature and participated in her college’s historic European martial arts (HEMA) club. My life was changed by my college course on the Crusades, in which my professor guided us through primary sources such as Usama ibn Munqidh’s Book of Contemplation and the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia and encouraged me to question simplistic narratives concerning the middle ages and the Middle East. Reading about history also helped me ground myself during the peak of COVID-19 pandemic. (I was not reading about the Black Death. I didn’t torture myself like that.) At some point, it stopped being something I did to write better fiction and started to be something I enjoyed for its own sake.

I’m not the only person to take refuge in the past. 2010s pop culture encompassed the blockbuster that was Game of Thrones and a cadre of more or less prestigious TV shows that rode its coattails, such as Vikings and The Last Kingdom, often featuring dull, brown sets and scowling anti-heroes in fake black leather. (Or wily and generically beautiful anti-heroines, whose legs and armpits in the compulsory sex scenes are somehow always shaven despite settings that loudly press their claims to realism.) Despite trying very hard, as a college student, to like these shows, I never felt welcome in this sort of medievalism—which I’ve come to think of as a dishonest, self-serious older brother to Megan Cook’s dirtbag medievalism that begs you to take it seriously, lacking the courage to embrace its own camp. At the time, I was bothered by these properties’ often blasé portrayal of sexual assault, using forms of systemic violence that affect as many as one in three women worldwide as provocative wallpaper, and since then, I have come to resent the projection of 21st-century misogyny on medieval settings. Gender in the historic middle ages was more complicated and interesting (she said, as she reads about medieval nuns being made masculine in their holiness).

These shows were not about the middle ages. They were about early 21st-century hangups with gender, sexuality, violence, and the intersections thereof. For some people, I think, the historical set dressing (such as it was) gave them license to explore fears—or fantasies—that would have been less comfortable had they played out in modern settings. For more people, I think it was comforting to imagine that the excesses portrayed in the 2010s GoTcore boom were confined to the past. And for yet others, I think, they simply provided an outlet for modern grievances, some of them legitimate, and some of them not.

In 2017, the Unite the Right rally occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia. I was living in another Virginia college town. By then, I had a sense of how rotten things were in my country, but the videos circulating on Twitter of tiki-torch-bearing, polo-shirt-wearing white supremacists shouting hateful slogans still shocked me, a white, middle-class 19-year-old who had naively and mistakenly believed that sort of overt bigotry belonged to the past. Among academic medievalists, white supremacists’ use of crusader imagery also sparked discussion of right-wing appropriation of the medieval past. As an undergrad, I did not have access to those conversations, but I’m grateful that, at roughly the time this was occurring, I had a professor who gently and carefully helped me and my classmates see that simple dichotomies of West vs. East, Christian vs. Muslim, crusader vs. saracen deployed in reactionary narratives did not match what was depicted in the primary sources.

Much ink has been spilled on the nostalgic, traditionalist, and backward-looking tendencies of fascism by writers more educated than I. Suffice it to say that although the extreme political right may invoke the medieval past in praise of that era’s perceived racial homogeneity, rigid gender roles, and Christian hegemony, the historical reality is, of course, much more interesting and complicated. The medieval world was interconnected and cosmopolitan: caliphs sent elephants to Charlemagne’s court, abbesses served as counselors to royalty, and a 12th-century Muslim nobleman counted members of the Knights Templar among his friends. In my experience, right-wing extremists rarely seem to admire the past for itself but use it as a cudgel to beat the present.

Moreover, the forward-looking, futuristic brand of fascism has at last begun to receive popular attention. Jordan S. Carroll recently wrote on reactionary futurism and scholarship on this topic in the Los Angeles Review of Books. Put succinctly, right-wing extremists envision a world in which technology empowers white men to become something like Nietzchean supermen bending the planet and the galaxy to their will. This is the future that Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and a host of other rich, unpleasant men whose names I am ashamed to know wish to bring about. It would be very easy and very comforting to imagine that the linear progression of time guarantees a steady march toward greater prosperity and greater freedom for all, including women, disabled people, Black people, Indigenous people, and queer people, but this is not necessarily true. That arc of justice won’t bend itself. The future may be no less oppressive than the past.

But we may find liberation in the past just as easily as in the future.

Medievalists Matthew Gabriele and David Perry have identified another kind of popular medievalism, dubbed “castlecore,” that has lately emerged in response to and critique of technofascism: the moody, fantastic, romantic (in various senses) medievalism embodied by Chappell Roan and A Court of Thorns and Roses. “The medievalism of castlecore offers people, especially women, a way to critique this tech-bro futurism without directly engaging the politics of the moment,” Gabriel and Perry write. “What’s more, it’s a way to engage in a kind of history that points toward a different kind of world, without being accused of being Luddites or becoming toxic nostalgics.” Whereas technofascism advocates contempt for democratic norms and human dignity, a philosophy of fuck-you-I-got-mine, castlecore embraces a fantasy of luxury and wealth, windswept moors and lonely manors, ballgown and armor, and distraught lovers.

I prefer castlecore to the defensive pseudo-historicism of early 2010s prestige television or the reactionary posturing of the late 10s. However, I’ve never been able to fully embrace romance, the commercial fiction genre, or its romantasy offshoot, despite enjoying a few stories in those categories. Many of these frustrations, I’m coming to realize, likely stem from my being on the asexual spectrum. Being single is not a failure or a betrayal of a promised happy ending.

Castlecore, like other forms of medievalism, is about the present. Although some scholars have found the origins of modern notions of romance in the high medieval ideal, or literary trope, of courtly love, these medieval stories were not romances in the modern sense. Medieval romance played on the tensions between personal desire and duty to one’s lord. They often ended in tragedy. Outside of literature, the medieval world was not the misogynist hellscape depicted in GoT and its ilk—although misogyny and sexual violence certainly existed, then as now—but most medieval men and women married people approved by their parents for the purpose of having children who could inherit and increase family wealth. The modern construct of romance is based on an ideal of marriage, or long-term partnership, as founded on mutual sexual attraction and emotional intimacy. In Western Europe and North America, this ideal has become widespread only since the rise of industrialization.

But none of the above necessarily concerns writers of stories set in imaginary worlds that never existed. This flattening of the past, or something that looks like it, occurs to some extent in any depiction, even nonfiction. The past is simply too big to fit neatly into anyone’s book—something I’ve become even more aware of since I turned to historical fiction.

Nonetheless, I propose that it’s possible to take comfort in the past as the past, not what we imagine it to be. What draws me to keep learning about the middle ages is the creativity, individuality, curiosity, and intelligence I continuously encounter when reading about medieval people, albeit from a distance. Medieval people fought wars and had their bigotries, like people of any age. They also cared for their families and friends, created poetry art, and sought to understand the world around them. Christians and Jews ate meals together in Carolingian Francia, even as Agobard of Lyon complained about it to anyone who would listen. A 9th-century cleric wrote a poem about their cat. Wars and plagues and other grim things were part of the middle ages, but so were the bright things.

But there’s even comfort in the grim parts of history, precisely because they are in the past. The wars and plagues and waves of persecution have come, and they have gone. Not everyone survives these crises, and the harm to the survivors is severe. My intent is not to minimize these events but to take heart in the fact that history doesn’t end in the pit—there are always survivors to rebuild. The Gododdin memorializes the annihilation of a 6th-century war band, but someone was left alive to sing of them.

It comforts me to think that no matter how bitter the current struggle, no matter how much it might preoccupy my mind or oppress my body, one day it will become the past. Through some mechanism I can’t foresee, history will turn over, and my generation’s fight will become distant events recorded in a book read by some future person who will have a struggle of their own. There is no end to history, and that is its comfort.

For as Leonard Cohen sang in “Anthem”:

The wars, they will be fought again

The holy dove, she will be caught again,

Bought and sold and bought again

The dove is never free.

Ring out the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.