So I Have a Story Out?

I had my first publication, and here are some thoughts about Egyptian Hieroglyphic script, which I promise are relevant.

by Abby Roberts

I meant to write and send this a week or two ago, but as you may be aware, especially if you’re American, some things have happened since then, which I’ve been kind of mad about. But anyways, yes, it’s true, I do have a story out. “A Hoard of Infinite Meanings” was published on Oct. 29 in Issue 153 of Swords & Sorcery Magazine, despite containing no swords and only a little sorcery. This is my first fiction publication, and I’m pretty excited about it, despite Everything.

I wrote “A Hoard of Infinite Meaning” in January of this year, as part of a three-month short story writing cohort led by Mary Robinette Kowal, of Lady Astronauts fame. I highly recommend Mary Robinnette’s cohort experience for anyone who wants to grow as a short fiction writer. During the cohort, my assignment was to write the first draft of a short story in stages over a 10-hour period. I reached deep into my brain and produced a story about a grieving linguist who rediscovers the magic in her work.

Below, I go into some of the real-world linguistics that influenced my writing of the story.

My Adventures with Middle Egyptian

“A Hoard of Infinite Meaning” is also based on my attempt to learn Egyptian hieroglyphics, as one does. Sometime late last year, I tracked down the second edition of James P. Allen’s Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. This book was recommended to me on several websites and other resources on the history of Ancient Egypt as an up-to-date introduction to hieroglyphs. That I didn’t succeed in learning hieroglyphs isn’t the fault of the book but of my limited time and resources, and the fact that learning a dead language is difficult.

Middle Egyptian is the form of the Egyptian language spoken between about 2100 and 2600 BCE, but it remained the standard written form of Egyptian for much of Egyptian linguistic history. It was preceded by Old Egyptian (about 2600-2100 BCE) and followed by Late Egyptian (about 1300-650 BCE), Demotic (about 650 BCE-400 CE), and Coptic (1st-11th century CE). Yup, Coptic, the direct linguistic descendent of the language inscribed on the walls of the pyramids, existed as a living language into the Middle Ages!! It’s still used as a liturgical language by the Coptic Christian churches, just as Latin was used as a liturgical language in the Catholic Church until the twentieth century.

Even as far as dead languages go, Middle Egyptian is particularly difficult to learn. First of all, there are fewer resources dedicated to it than other well-known dead languages. I’m able to learn Latin through my local community college. Good luck finding classes on Middle Egyptian unless you’re a student in select grad programs. Second, Middle Egyptian isn’t as well understood as Latin or Ancient Greek, since it doesn’t have a living descendent. It’s like if we had to learn Latin without the wealth of linguistic evidence—for pronunciation, morphology, syntax, etc—provided by the Romance languages. As if we were trying to reconstruct Latin in an alternate universe where only Italian survived until about 1000 CE.

Third, Middle Egyptian is from the Afroasiatic language family, a different family than Latin or Ancient Greek, which are Indo-European Languages. As an Afroasiatic language, Middle Egyptian shares similarities with Hebrew, Arabic, Hausa, Amharic, Somali, and the Berber languages. Words in Afroasiatic languages are based on sequences of three-ish consonants, with vowels and affixes plugged in to shift the meaning. For example, the root k-t-b appears in many Hebrew and Arabic words related to writing. Arabic kitāb “book”, katabat “she wrote,” maktab “desk” or “office,” maktabat “library” or “bookshop”; Hebrew kātabti “I wrote,” kattebet “reporter (feminine),” kettubā “marriage contract.” And so on. All stages of the Egyptian language use two-, three-, or four-letter roots in a similar way, but this is only so helpful because Egyptian belongs to its own branch in the Afroasiatic family tree and is not closely related to the other surviving languages.

Fourth, hieroglyphs, the main script used to write Middle Egyptian, presents challenges in itself, some of which I will get into below.

The Loss of Hieroglyphic Script

The protagonist of “A Hoard of Infinite Meaning,” Seshet, is a linguist working to decipher the Sacred Script, so-called because it has magical powers attributed to it, which was used by the lost civilization of Tawi. In the story, Tawi was destroyed in an event that I imaginatively called the Cataclysm to provide a suitably dramatic explanation for why the Script was no longer understood in Seshet’s time. But in the real world, changes in language and culture over time were enough to cause the ability to read hieroglyphic script had died out by the fifth century CE, when the latest known hieroglyphic inscriptions are thought to have been made.

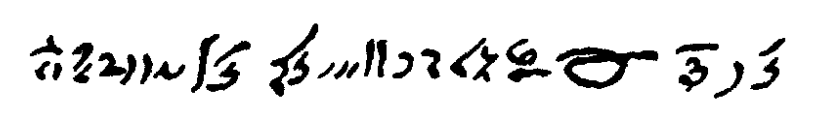

But wait! I imagine you saying. But wasn’t Coptic spoken into the Middle Ages? How did the script die out but the language did not? The answer is that going back to the Old Kingdom, the very beginning of Egyptian civilization, hieroglyphs were never the only script used to write varieties of Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs were used in religious and formal contexts, but in non-religious, everyday use, a cursive form of hieroglyphs developed into hieratic script developed into Demotic script. Then, in the early centuries CE, Egyptian Christians didn’t want to use a script associated with polytheistic traditions, so they adopted a script derived from the Greek alphabet, later known as Coptic script. Coptic existed alongside the Demotic, hieratic, and hieroglyphic scripts for hundreds of years. But as Egypt became first predominately Christian and then predominately Muslim, the other scripts gradually died out, along with Egyptian polytheistic religion. In the early 19th century, a Syrian-Egyptian monk named Anton Zakhūr Rafa’il taught the Coptic language and script to a French linguist named Jean-François Champollion, but by then, no one had been able to read hieroglyphs for more than a thousand years.

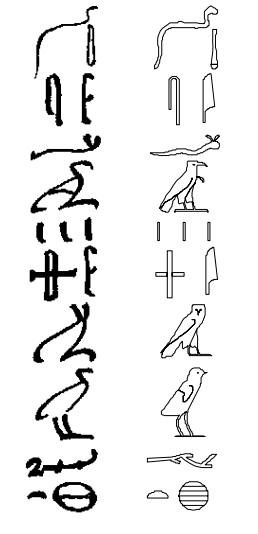

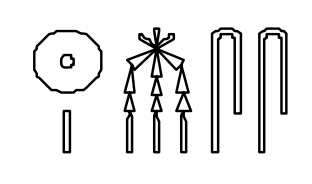

You can see examples of each script from Allen’s book below:

(Incidentally, the Coptic language and script has its own rich history, which is worth learning about. Anglophone scholarship tends to overlook parts of history that don’t fit into a linear narrative of progress leading from the Bronze Age to modern Britain or the United States. Ptolemaic, Roman, and medieval Egypt weren’t lesser, corrupted versions of the civilization of the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms. Egypt has a history after the end of Pharaonic civilization, just as Greece has a history after the end of classical civilization, and just as the Roman empire existed for another thousand years after the disintegration of its western half.)

False Starts and Decipherment

The loss of understanding of hieroglyphic script did not stop people from trying to decipher it. Likewise, in “A Hoard of Infinite Meaning,” scholars have been trying to decipher the Sacred Script of Tawi for four millennia. This length of time is much longer than the time between the last use of hieroglyphs in the 600s CE and their decipherment in the 20th century, which might stretch historical linguists’ suspension of disbelief, but it’s good for drama.

The early antiquarians and linguists who tried to decipher hieroglyphs made many false starts and mistakes due to their lack of understanding of how hieroglyphs. For hundreds of years, people believed that hieroglyphs represented ideas rather than sounds. This belief originated from a text attributed to an Egyptian priest known as Horapollo in the fourth century CE. Horapollo, or the person writing under that name, possibly had some, incomplete knowledge of hieroglyphs, but remember, the script was dying out by this point and no longer in popular use. Horapollo claimed that hieroglyphs were allegorical, symbolic, or ideographic—that is, conveying ideas, not sounds. Horapollo wrote, for example, that the word for “son” was written using a hieroglyph resembling a picture of a goose because Egyptian people loved their children as much as geese loved their goslings. Yeah, really.

Needless to say, Horapollo was dead wrong. Egyptians wrote their word for “son” using the goose hieroglyph because the Middle Egyptian word for “son” contained the same sound as one of the words for “goose.” The relationship between the words for “son” and “goose” were coincidental, an accident of linguistic evolution, just as the English word “belief” is not related to the words “bee” or “leaf,” even though they include the same sounds. Put a pin in that. It will be important later.

Horapollo sent generations of linguists on, I’m sorry, a wild goose chase. This isn’t how hieroglyphs work. This isn’t how any writing system in the world works. All scripts essentially encode sounds rather than ideas. No purely ideographic (ie, the signs map to ideas, not sounds) script exists. Chinese script is often referred to as ideographic, but it, along with a few other scripts invented completely from scratch, by people who had never encountered written language ever before, including Sumerian and, yes, Egyptian, are technically referred to as logographic. That is, symbols represent words or morphemes—the smallest meaningful components of a language. Logographic scripts combine signs representing ideas with signs representing sounds, as needed to disambiguate meaning.

(On the topic of purely ideographic scripts not being a thing that exists—just think about it. Book translators’ jobs would be so much easier if all the nuances of linguistic meaning could be represented in a single universal script that purely conveyed ideas, with no connection to a system of sounds. But this doesn’t happen. We can’t write books entirely in emojis or hazard pictograms. The problem of accurately conveying meaning through signs without using language or culturally contingent symbolism has vexed for decades scientists and governments, among others, such as in long-term nuclear waste warning messages.)

I will get into how hieroglyphic script actually works in the next section, but for now let’s return to Jean-François Champollion, Anton Zakhūr Rafa’il’s student who would decipher hieroglyphs. The seventeenth-century antiquarian and Jesuit Athanasius Kircher had suggested that the hieroglyphic script may have been phonetic and that Coptic was the last stage of the Egyptian language, which wasn’t widely known at the time. But Kircher was very bound up in occult interests and his translations of hieroglyphic texts were inaccurate. Champollion and a few others, such as Englishman Thomas Young and Swede Johan Åkerblad, took up Kircher’s line of attack two hundred years later.

Champollion looked at royal names in cartouches, including on the Rosetta Stone, a stele inscribed with a decree issued in the second century BCE by Ptolemy V, which includes text in the Greek and Egyptian languages, in Greek, Demotic, and Hierographic script. The names “Ptolemaios” and “Kleopatra” gave Champollion hieroglyphic signs that he associated with the values “p,” “t,” “o,” “l,” “m,” “i,” “s,” “e,” “a,” “t,” and “r.” (The second “t” is more often transliterated as “d” these days, but also, Middle Egyptian probably did have multiple “t”-like sounds. I was going to Get Into It but Buttondown doesn’t handle footnotes well.) Then, Champollion began working on the cartouche that ended with two hieroglyphs he valued as “s.” The first sign in the cartouche was a round disk, which reminded Champollion of the sun and the Coptic word for “sun,” rē. From there, he recalled the name of Ramesses, known from a Greek history of Egypt written in the fourth century BCE, and guessed that the middle sign might represent a sequence of sounds something like “mes.” He checked his guess by comparing it to the bilingual text on the Rosetta Stone.

I tried to represent something like Champollion’s process of decipherment in “A Hoard of Infinite Meaning.” Within the setting, scholars believed for thousands of years that the Sacred Script was ideographic. Seshet’s mentor, Darush, had discovered that the Sacred Script of Tawi was phonographic, not ideographic—as Seshet explains to her non-linguist friend Imat. Like Champollion, Darush had succeeded in transliterating the names of Tawi kings and queens, but before he could prove his discovery, he died. His student Seshet is left to carry on his work, despite her grief and insecurities.

How Do Hieroglyphs Actually Work?

In Egyptian, the name “Ramesses” meant “the sun is the one who gave him birth.” In Ramesses’ cartouche, the disk-shaped sign represented both the idea of the sun and the sequence of sounds that happens to mean “sun” in Egyptian. It’s similar, although not quite the same, as if you wrote the English word “belief” as 🐝🍁, a picture of a bee (flying insect) next to a picture of a leaf (from a tree). In the case of “Ramesses,” it’s not, in fact, totally arbitrary that the sun sign is used—“sun” is part of the semantic meaning of the name, and the sun was an important symbol of royal Egyptian power—but there were plenty of Egyptian words that did follow the belief/🐝🍁 pattern, such as the “son”/”goose” example mentioned above, which I won’t try to represent here, because it would require special characters my keyboard doesn’t support.

This is the rebus principle—using a symbol to represent a sequence of sounds, regardless of semantic meaning. As if the entire English language was written out using sequences such as 🐝🍁 or 👁️❤️🐑. The basic principle on which hieroglyphs “work” as a script. In practice, however, some signs were primarily used to represent sound values, while others were mainly used to represent the concrete objects they actually depicted, and others were used as determinatives, to mark what kind of word was being referred to, such as a pronoun or an action. Some signs could be used in two or all three ways. Some signs represented only one sound, whereas others represented sequences of two, three, or four sounds—or various combinations, depending on context. Ancient Egyptians mixed and matched phonograms, ideograms, and determinatives to disambiguate similar-sounding words or homophones. As Egyptian spelling wasn’t standardized, this meant you could find the same word spelled multiple ways in different texts, or even within the same texts.

Oh yeah, and while the examples above don’t really make this clear, speakers of Egyptian didn’t write vowels until Coptic script came into use. This is pretty common with scripts for Afroasiatic languages; you see it in the Arabic and Hebrew scripts too. Regardless, there’s a kind of logic to hieroglyphs, but it’s tricky to get used to if you’re accustomed to the English alphabet, or something like it.

To me, the idea of signs that could represent both sounds and ideas was so incredibly cool that it found a way into “Hoard.” As Seshet discovers, after having a cup of tea and getting pressured by her friend Imat into doing therapeutic manual labor, when signs of the Sacred Script are combined, they represent sounds or clusters of sounds. But when signs are used independently, they’re imbued with magic that allows the user to influence or manipulate the world around them through supernatural means. Seshet accidentally uses a Sacred Script sign causing some garden herbs to grow, which leads to her realizing that perhaps the Script signs represent both meaning and sound, instead of just one or the other. I also think I had some vague notions related to semantics and maybe historic occultism floating around in my mind that I won’t try to explain here because I’d only mangle them.

But I did have to make clear in the story how the Sacred Script “worked,” since the climax of the story is when Seshet finally gets a lead on deciphering it, and this ended up being real tricky to do. Seshet makes a breakthrough on the Script by recalling a popular trend in her world, when people used the symbol of a heart to represent the word “love.” I like this example because it’s something that readers can recognize from their own experience, but it was hard to come up with. Seshet is not of our world and doesn’t speak English and wouldn’t associate any symbol with English sound values at all, and she would probably have different cultural associations between symbols and ideas than we do. I’m fully aware that this is a fantasy story and that I can simply make things up to make the story work, but issues of meaning and culture are things I think about a lot. It was also really, really difficult to explain all the linguistic concepts and Seshet’s thought process that led to her breakthrough in terms that would make sense to linguists, that non-linguists could understand, and that wouldn’t be unforgivably boring. I think I may have reached a compromise between all three of these goals, but I still spent a lot more space on explanation in this story than I would prefer.

Something less difficult, but that I still struggled with a little, was conveying that Seshet had made progress without making it seem like she had cracked the Sacred Script in a single afternoon all on her own. Scholarship is not the work of a solitary genius who has a sudden strike of inspiration. It’s a long, slow, often frustrating process, through which many people build on each other’s work over many years. That’s the reason why I framed Seshet’s work with the Script within her grief for Darush and her feeling that she’s inadequate to live up to his legacy. Seshet’s real breakthrough at the end of the story isn’t that she’s finally got the Script all figured out, it’s that she’s reenergized, that she has hope and a new direction for her work.

What Am I Doing?

Writing. I am working on a couple of essays that I hope folks will see eventually, although I won’t say any more about them now. I’m also trying to hack out a newsletter about Bad Medieval History Takes. By the way, big shout out to Joe Bruhler on Bluesky who helped me track down a copy of Frank Sheed’s 1942 translation of Augustine’s Confessions, which I needed for reasons and barely anyone seems to have.

I have a bunch of short fiction I need to edit and do something with but honestly, I’m kinda maxed out right now.

Also, while I would never commit so egregious a breach of copyright law, someone (cough cough) has started writing a Lord of the Rings fanfic about things Aragorn did before the War of the Ring and how he became the way he is. You can read the first chapter on AO3, if this is your thing.

Reading. I finally finished Chris Whickham’s The Inheritance of Rome, which provides a good overview of late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. The focus is on Carolingian Europe, mostly France and Germany, but the book also addresses the Iberian peninsula, Celtic, Norse, and Slavic areas, the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Arab world. I have also been listening to the audiobook of The Spear Cuts Through Water by Simon Jiminez and enjoying it immensely.

Watching. Honestly, I’ve been too busy to watch things. I still need to watch the last episode of The Rings of Power, but I don’t have a moment to myself. I’ve enjoyed parts of the new season and some parts not as much as others, but that’s fine. It’s TV. I watched a few episodes of King of the Hill the other night to unwind.

Miscellaneous. This doesn’t really fit with anything else but I’ve also been learning Latin through my community college and that’s been taking up a lot of my time, along with watching the world burn on Bluesky.