It's still what computers still can't do

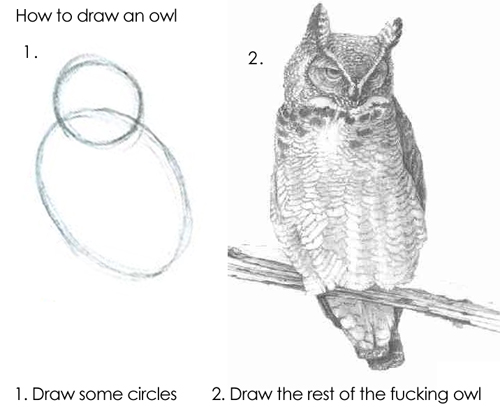

The New Yorker writer John McPhee, perhaps the 20th century's greatest writer of descriptive non-fiction, published a late-career book on writing called Draft No. 4. In that book decocted seven decades of his writing career into a set of writing lessons. Leaving aside that the idea of a method to learn to write like John McPhee, one of the most gifted and precise prose stylists in the modern era, has a bit of a flavor of the "and now draw the rest of the owl" meme, the book is fascinating. It describes McPhee's deeply idiosyncratic method for producing deeply reported, long-form articles and books on highly complex, often scientific topics that are narratively gripping while being exceptionally clear and precise.

John McPhee's method involves, first, a long phase of reporting, where he goes and talks to everybody he can find who might have something relevant to say about the broad topic of interest. Alaska, the geology of North America, suitcase nuclear weapons, tennis, a whole book about oranges: whatever the topic, he would aim to get as broad a cross-section of interesting perspectives as possible, taking trips with his sources and getting to know them. So far, impressive but normal. He would then take those interviews and cut them up into individual story beats, quanta of narrative. So far, conscientious but basically what I would have expected.

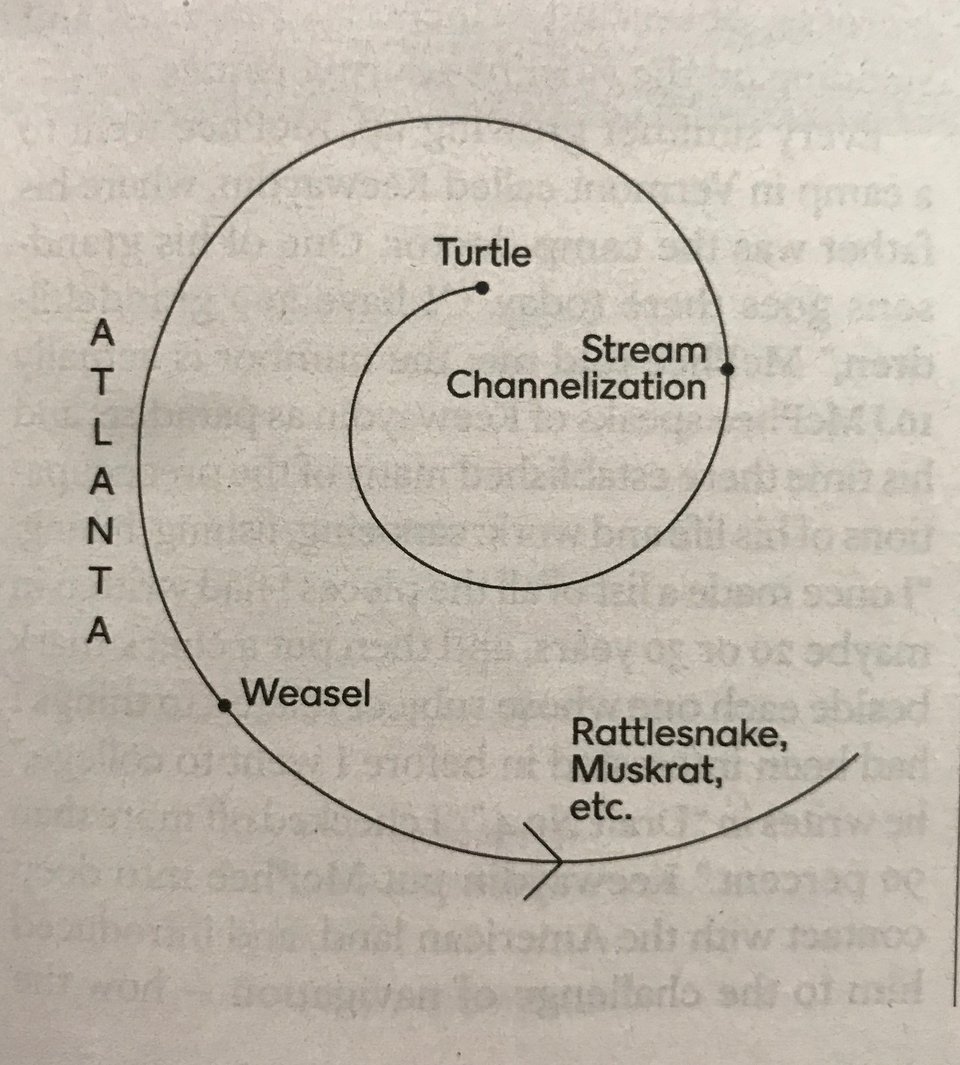

What he does next is unexpected: with the notes he's taken in mind, he draws a shape on a piece of paper. He gives examples of these shapes in his book, simple line drawings that look like spiders, or boxes, or spirals attached to vertical stems. These shapes, in his telling, are the shape of the narrative he intends to create, the path through the information he has collected that will elucidate it, and allow people to see what he finds so fascinating about the topic. He then, in his telling, pins the shape to a board and starts arranging the individual beats of the story to fit that shape. When the contours of the shape he has found are filled in with story beats from his notes, he has his narrative, and he sits down and writes the story.

This method is unusual, to say the least, and the idea of trying to follow it oneself presents very much the question of drawing the rest of the owl. You can see the results of it, though, in his books. One of my favorite John McPhee books is Levels of the Game, about Arthur Ashe, and possibly the best book ever written about tennis. The narrative is written as a shot-by-shot recounting of a single match between Ashe and his great rival Clark Graebner, contrasting the two men in their tennis but also their backgrounds and personal makeup. (See! Levels.) There is an extraordinary moment early in the book. It is focused on Ashe, as he prepares to make a shot. In a frozen moment just before he contacts the ball, the narrative shifts into his head, and describes what he is thinking and feeling in that moment. Then it travels back in time, to his upbringing, his parents and grandparents, and back through the tribulations of his family tree all the way back to the moment of his ancestors' transport to the US in the hold of a slave ship. Then it pops back to the game as Ashe hits the ball. Do you see the shape?

I recently read a different, more recent tennis book. I won't name it, because it's really very good on its own terms—a good story, wonderful sentences, perfectly diverting—and it's hardly fair to negatively compare anybody's writing to that of John McPhee. But as I was reading I realized that there was something I found unsatisfying about it. The shape of the narrative was fundamentally linear, a story of things that happened roughly in the order that they happened. The shape—this completely idiosyncratic authorial decision point that John McPhee turns out to be obsessed with—was not strong enough to support all the incident hanging from it without sagging.

What does this have to do with 'AI'? We are at an intensely polarizing moment for the collection of technologies assigned that name. There are good reasons for this. The chaotic and too-early rollout of direct-to-consumer LLMs is one. The lack of useful applications and the preponderance of embarrassing failures, especially in the context of immense top-down pressure to use these tools in businesses of all sorts is another. The big ‘AI’ companies, with limited and occasional exceptions, have seemed more focused on making unsupportable claims about the future than in evaluating what would make LLMs useful and not pernicious. In the corners of the internet I inhabit this has inspired a truism among those who are (appropriately and correctly) skeptical of 'AI' that it can't really do anything, that as a useful technology it has failed. They are at odds with a second group, though, who may be very skeptical indeed of the big 'AI' companies but who have tried using the technology and found it astonishingly, even terrifyingly useful, useful (initially, if not solely, for software engineering--really most anything where it's not expressive work and there are explicit, formal measurements of what success looks like, which is a BIG category) in a way that makes them feel like they need to warn the world of the changes that are afoot. This second group are not triumphalists. But they have found the technology transformative and believe (again appropriately and correctly, I would say) it is on the cusp of transforming and disrupting society in turn.

The heart of this disconnect is that the boundary between what 'AI' is good at and bad it is hard for people to see. Moravec's Paradox tells us that the things that ML/'AI' will have the most trouble with are the things that humans find easiest. Things that are effortless for humans are done automatically, and things that we do automatically are hard to introspect about. These effortless cognitive abilities include things that are so central to how we exist in the world, in fact, that we have trouble even conceiving of what it would be like to lack them. Theory of mind reasoning is an example I've returned to again and again. Many of the strange lacunae in the present functioning of 'AI' comes down to a lack of a real theory of mind. There are other, related, functional absences. The matrix of valence and arousal generated by the parts of our brains that are not well-represented in LLMs—the peripheral nervous system, modulatory neurotransmitters, the rhythmic, spatiotemporal dynamics of brain activity—provide a richness and, for lack of a better word, embodiedness1 to our continuous existence in the world that does not exist in the vast association networks of modern transformer models. This matrix is how we develop a theory of mind. This matrix—these same mechanisms—also ensures that we go through the world with a perspective.

I don't want to get too far down the philosophical path with this, not least because other people do it much better, but every part of our cognition and behavior in the world is suffused with and defined by what we want and who we are at a moment-by-moment basis. Having a perspective on things, seeing and moving through it in our own unique and idiosyncratic way, is so central to the phenomenon of being a person that the question of what it would be like to lack that--what perspectivelessness would entail--feels unanswerable.

The idea that the cognitive implications of human existence in the world were going to present a challenge for modeling intelligence automatically is not a new one. Early AI2 researchers were very confident that they would soon be able be meaningfully simulate the capabilities of the human brain. Their claims were so confident and so broadly disseminated that Hubert Dreyfus, a Heideggerian phenomenologist drafted somewhat incongruously into the role of early AI skeptic, found himself moved to write a tremendously influential 1972 book called "What Computers Can't Do". In this book Dreyfus examined the symbolic AI approaches of the time from the perspective of phenomenology, and identified a litany of tasks that were simple for humans that these systems would never be able to accomplish, and described them succinctly in terms of the lack of situatedness in the world and wants and needs.

Dreyfus's books—he revised the original, more certain of his central points than ever, in 1992—have grown in stature over time, and been taken increasingly seriously by people working in 'AI'. In many ways the present approach to 'AI' takes his considerations in mind and is more or less the approach that Dreyfus found the most promising. But the argument that machine intelligence lacks something that comes from humans' phenomenal experience of the world is not easily laid aside. Even modern massively-scaled, connectionist statistical engines are missing massive and centrally important pieces of the neural infrastructure that makes a person a person. This remains true even as these models grow massively large and, girded and controlled by increasingly elaborate infrastructures of harnesses and guardrails and agent coordinators, increasingly capable.

What these systems still can't do, as predicted by Dreyfus, is have a real point of view, or to understand somebody else having one. The vast architecture which takes our multifarious and constant direct experiences of the world and reduces its dimension to act as a control signal for the parts of our brain that do statistical completion and pattern matching still isn't there. The vast association networks in an LLM—neatly and evenly correctly analogized to the big association areas of the brain, like the prefrontal and anterior parietal cortices—operate with a sort of perspectiveless blankness, tumbling obligingly along whatever paths of inference are available to them without any overarching or persistent understanding of a narrative existence.

Which brings me back to John McPhee. When he is drawing his funny little drawings what he is really doing is figuring out what path he's going to lead readers on in his stories. He's figuring out how to organize his own perspective on a million related but disparate facts and turn it into a journey that he can take, but more importantly, that he can take somebody else on. The central premise of his approach to writing is centered on who the reader of his stories will be, and how he can help them see what he can see. The shape that he draws is a path that he, operating as himself in the world, can take a reader on so that they see the things he can say, in the way he wants them to learn to see them.

LLMs can't find the narrative perspective that unlocks a story. Their own existence—their being-in-the-world, to clumsily borrow a phrase of Heidegger’s used by Dreyfus in his phenomenological work—is too impoverished to think about the text they are producing as a reader. They are immensely capable of organizing large masses of text, but the organization they chose will be the organization that has been most commonly chosen before. It will be inherently perspectiveless, because they have no perspective to add. They can't draw a path that the reader or viewer can follow to see the world as they do. They have no access, in short, to the shape. They can construct language that is fit for purpose. They can take large amounts of information distill it down. In many cases, like software engineering, this is more than enough for extraordinary, even world-changing facility. But they can't produce output that helps you see things from a specific perspective, because the generation of that output is perspectiveless by necessity, and that means that they can't produce outputs that carry the spark of creative identity that makes writing—and visual art, and music—interesting to consume.

The question of whether 'AI' needs to be embodied is an ENDLESSLY controversial one in the field, where people get hung up, often for years, on definitional questions, and I use the word reluctantly because I don't want to get into that here. ↩

I feel no obligation to use the scare quotes for 1950s and 1960s AI because what was happening then really was an effort to produce artificial human intelligence, as they problematically understood it ↩