Human Limits/God's Holiness | SL 3.1 (October 2021)

In this newsletter

- Human Limits

- Work & Ministry Update

- A Note on the Artwork

- Leviticus & the Meaning of Holiness

- Pray With Us

You can always read this newsletter in your browser.

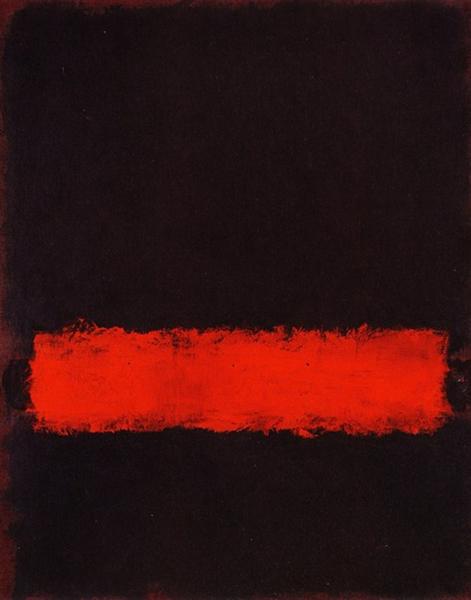

Orange and Yellow (1956) by Mark Rothko, image from wikiart.org.

Human Limits

So far, my 30s have been about coming to terms with my limits. I used to have a mentality (unstated!) that I should be able to do everything that would be good to do. If I was unable to do all that I wanted then there was something wrong with me. But this is a pernicious lie.

I recently read a book that reminded me how far God has brought me in coming to terms with these things. It’s called 4,000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman. This is the anti-productivity book. Burkeman analyzes the modern obsession with time, time management, and productivity and reveals it for the ever-receding chimera that it is. The more productive we become, the more we fill up our time, the more we think we can accomplish, or ought to accomplish, and the more overwhelmed and finite we feel. But when we accept our limitations, we begin to be able to live like mortals in the here and now. This is a good thing.

Burkeman takes the classic productivity advice from David Allen’s renowned Getting Things Done and deconstructs it. In that book there is a metaphor for our lives. Imagine you have a jar (your life) and you have big rocks, little rocks, and sand that you have to fit into the jar. If you start with the sand and pebbles, the big rocks won’t fit. But if you start with the big rocks (i.e., focus on the hard/important things), then everything else will fill in the cracks. Right, says Burkeman, but Allen has rigged the illustration. He’s taking it for granted that your jar is big enough. The reality for most of us is that there are just too many big rocks on the table. It’s a disingenuous recipe for shame and discouragement to suggest that you should be able to fit in all the big rocks. To be faithful, some rocks must stay on the table.

If you live to be 80, you have 4,000 weeks. There is no more time to wring out of life, it is just a matter of how you use what you’ve been given. This isn’t just a sort of vaguely Zen bit of self-help advice. I think it’s faithfulness before God. Honestly, as I read 4,000 Weeks, I felt that Burkeman had simply discovered the central theological contribution of the book of Ecclesiastes. There is nothing that human beings can do to transcend our mortality (Eccl 3:19–20; 8:8). We are fully dependent on God and often ignorant of how this works (Eccl 3:22). Faithfulness is obeying him and enjoying life (Eccl 2:24–25; 9:7; 11:9).

Over the past few years a demanding teaching/travel schedule, a PhD program, and our growing family (not to mention injuries, an international move, and a global pandemic) have forced me to come to terms with these things. The best productivity advice is really about embracing and working with your limits. In addition to Burkeman’s book, here are some perspectives I’ve found meaningful.

- I recently listened to a podcast episode with former pastor turned leadership coach, Carey Nieuwhof, about his book At Your Best: How to Get Time, Priorities, and Energy Working in Your Favor. I’ve not read the book, but this episode was excellent. Important to hear these things from a pastor, since I’ve found people in ministry (including me!) to be particularly resistant to accepting their limits.

- Here’s a thoughtful Christian review of 4,000 Weeks by John Inazu. His critique is right on, but he also convinced me to get Burkeman’s book.

- Finally, many of you will know that I’ve personally found Deep Work by Cal Newport to be nothing-less-than-life-changing. This is especially true if you pair it with Ecclesiastes.

I’ve been reflecting on these things over the last couple of weeks, because I’ve started to feel my limits again. The PhD deadline is approaching. Opportunities to travel and teach are on the horizon. All of a sudden I have multiple projects to prepare for, different logistics to keep track of, and therefore “less time” in my day. In November I’ll teach courses in Africa and in Colorado then give a paper in Texas. This is all very good. I can’t wait to get back out there. I’m particularly excited to be heading to GraceLife Seminary in Monrovia, Liberia. I’ve never been before, but I have heard about this incredible school with exceptional programs and impact for years. Next month, I hope to write this newsletter on the ground in Liberia and give you a guided tour.

In all this, however, we must learn to be gentle with ourselves and not expect more than what God has given us to do.

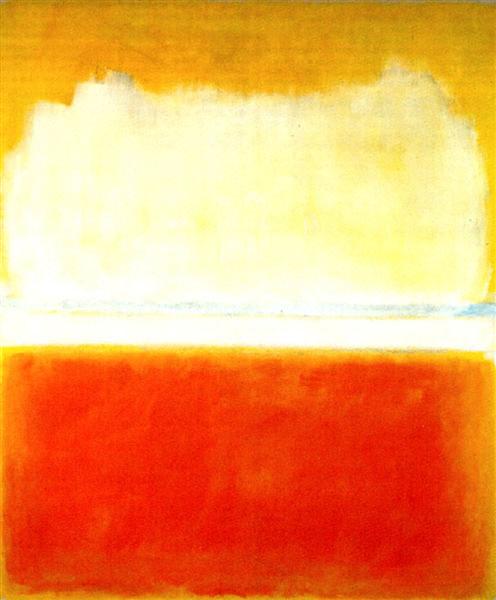

No. 61, Rust and Blue (1953) by Mark Rothko, image from wikiart.org.

You are Training Pastors to be Faithful to Scripture & Strengthening the Global Church

- Fall teaching is upon us! The logistics, visas, syllabi, plane tickets, etc., seem to be lining up. I leave on November 2 and I’m looking forward to teaching Exegesis of Proverbs for the MDiv students at GraceLife Seminary in Monrovia, Liberia with Training Leaders International from November 3–10. Then from Monrovia I fly to Denver, Colorado where I’m teaching a course on the Pentateuch for a new cohort of students at William Tennent School of Theology from November 15–19. After that it’s off to San Antonio where I’ll deliver a paper comparing Proverbs 30 to Isaiah 13–14 at the Society of Biblical Literature annual meeting on November 21st. Then home!

- Before I do any of that, however, I’m headed down to Oxford on October 18th to do a guest lecture on Deut 6:1–9 at Wycliffe Hall. My good friend, John Screnock, is the new OT tutor there and he’s invited me down for a few days. Really looking forward to the chance to interact with some of the top OT scholars at the world’s oldest English-speaking University.

- The PhD dissertation is entering the final stretch. The goal is to submit in the Spring. Over the course of the Summer I drafted and redrafted the outline and structure of the whole thing. My supervisors suggested that at this stage I needed to hammer out the argument as a whole, which is a lot harder than it sounds (especially since I thought I had already done this!?). But after about seven attempts I think I’ve got it figured out. Currently at work drafting “chapter 5,” which is about Prov 30:1–10. Chapter 6, which is already partially written, will deal with vv. 11–33.

Thank you. Your prayers and support empower everything we do.

Red (1964) by Mark Rothko, image from wikiart.org.

A Note on the Artwork

Despite the fact that my mom and brother are visual artists, I’ve never felt like I truly “get” the grammar of the medium. But, I know when something connects with me. I believe that every work of art says something unique—something irreducible that can’t quite be expressed in any other way. One of the first artists who really brought this idea home for me was American abstract painter, Mark Rothko. He is best known for the “color field” paintings I’ve included here. Rothko was Jewish, born in Latvia but immigrated to the US when he was 10. In many ways he lived a dark life that ended in loneliness and sadness, but I find that his paintings capture an incandescent transcendence. When I was thinking about the concepts of human limits and God’s holiness, Rothko’s paintings came to mind. Each painting seems to perfectly embody an emotion or a concept in color and space. Many of the darker ones capture the weight and boundedness of human life in tones of sin. But the brighter ones point to God in that they seem to have their own inner radiance—like the light and color are coming out from within. The different fields of color painted within each other reminds me of the grace of God that he lives with us.

Black, Red, and Black (1968) by Mark Rothko, image from wikiart.org.

Leviticus & the Meaning of Holiness

(Part VIII in The Theology of the Pentateuch)

I’m back to my long-running series on the theology of the Pentateuch. This is the first of a two-part study of Leviticus. In this month’s newsletter, I’ll attempt to unpack holiness within the context of Leviticus and next month I’ll attempt to connect holiness and the law to our lives in Christ.

Everyone has a theology of holiness.

In his excellent book, The Righteous Mind, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that everyone has the sense that some behaviors are wrong because they defile us. But modern ethics struggles to explain these moral intuitions because it is based on concepts of autonomy and harm. The mantra is, “Everything’s okay as long as you don’t hurt anyone.” Haidt gives some extremely graphic and chilling examples that undercut that simplistic assumption. For now, we can probably all agree that it would be wrong to urinate on a grave (even if no one saw you) in the same way that it would be wrong to use a nation’s flag for toilet paper. And we would all feel that it was “just wrong” to eat lunch while sitting on the toilet.

Everyone has a theology of holiness. The concept of the sacred is buried deeply in humanity. You can’t ultimately explain these feelings without recourse to God. Holiness operates in this matrix. The spectrum from God above to pure evil below structures our experience of repugnance. Defiling agents are actions, events, and objects that move you “down” the scale, degrading your humanity.

When God says, “Be holy because I, the Lord your God, am holy” (Lev 19:2; 1 Pet 1:16), he calls us to reflect his character and his nature by being like him. The book of Leviticus guides us in this by rightly orienting our disgust mechanisms so that we recoil from sin and move toward God.

Holiness All the Way Down

The word “holy” in the Old Testament isn’t really an abstract noun, i.e., “holiness.” Instead, the bare noun means “holy place” or “holy thing,” but more often it is used as an adjective. It also frequently occurs as a verb, i.e., “holy-ize,” or consecrate/sanctify. Only in a few places, where God is described as swearing by his holiness, do we find something like the abstract concept (Ps 89:35; Amos 4:2). And this leads to the fundamental point: Only God is inherently holy, i.e., holy in and of himself. Everything else (objects, people, time, space) has a derived holiness that comes from God. It is typically argued that to be holy is to be separate, but since God is the fundamentally holy one and all other holiness is derived, it may be more accurate to say that to be holy is to be like God.

What is it about God that makes him uniquely and definitionally other? The revelation of God’s name in Exodus 3 and 34 is a good starting point. God is holy because he is self-defining. He is himself. He is Creator—outside of creation and distinct from all that is. He is morally perfect and the definition of morality. He is good when all else is corrupt.

But as Leviticus 10 vividly and poignantly shows us, God’s nature presents a problem for sinful humans.

Lev 10:1–3

1 Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu took their censers, put fire in them and added incense; and they offered unauthorized fire before the Lord, contrary to his command. 2 So fire came out from the presence of the Lord and consumed them, and they died before the Lord. 3 Moses then said to Aaron, “This is what the Lord spoke of when he said: “‘Among those who approach me I will be proved holy; in the sight of all the people I will be honored.’” Aaron remained silent.

God cannot be in the presence of sin—not because the sin will corrupt him—but because his purity will destroy and burn up what is sinful. The sun is an excellent analogy. It is life-giving and powerful, something that brings massive good to us, light, warmth, life. But if you get too close to the sun you die. You die because of all the properties that make it beneficial.

So how can the holy God dwell with a people corrupted by sin, unclean and impure from the inside out? This is the fundamental theological problem that is symbolized in the burning bush (Exod 3:1–6). The entire book of Leviticus can be understood as an answer to that question, and the answer is found in the structure of the cultic system and ritual law.

The terminology and concepts in Leviticus can get confusing. I think this diagram helps visualize them. There are two main polarities clean/unclean (AKA pure/impure) and holy/common (AKA sacred/profane). Sins and defiling agents move you toward “death” and away from YHWH; sacrifices, washing, anointing, etc., deal with sin and defilement so you can move toward YHWH.

“The way to holiness, in other words, was for Israelites, individually and collectively, to emulate God’s attributes” (Levine, 256.). This makes sense to us with regard to moral law (i.e., “Thou shalt not murder”), but how does ritual law connect (i.e., “Do not trim the edges of your beard”)?

Here’s the key to the ritual system: Since holiness calls us to imitate God, and some of God’s holy attributes are incommunicable (i.e., humans cannot share in them, such as eternality or omniscience), they can only be imitated analogically through symbolism.

There is an encoded symbolic logic to ritual. The basic organizing principle seems to be that holiness is associated with life as opposed to death and purity and wholeness as opposed to dilution, separation, or mixture. Death is the consequence of sin, and impurity is the symbolic representation of death. Defiling agents all seem to be related in one way or another to symbols of death, mixture, or dilution. Therefore sin makes you ritually dead, i.e., impure. Defiling agents (which symbolize death) make you ritually dead, i.e., impure.

Sin and impurity are not the same thing. Sin and pollutants both make you impure, but impurity is not sinful. The classic example is childbirth (Lev 12:1–8). Childbirth is not wrong, but it does make you impure because the blood reminds us that we are finite and on the edge of death because of our sin.

Because sin and pollutants both make one impure they are dealt with side by side. Leviticus links every aspect of life to our ability to dwell with God. The Israelites were meant to be a people rooting out sin, defying death, and orbiting the LORD’s holiness. Holiness is not asceticism, deprivation, or dourness—but a radical affirmation of life. Holiness is not passive, it does not draw back. Rather it is active, burning up sin and impurity.

God makes us holy.

The book of Leviticus is structured in seven sections with an epilogue to show how God makes his people holy (If I remember correctly, this structure comes from Tim Mackie at the Bible Project).

A. Ritual: Sanctifying People and Space: The Sacrificial System (Leviticus 1–7)

B. Priesthood: Ordination of the Priests (Leviticus 8–10)

C. Purity: Ritual Codes (Leviticus 11–15)X. The Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16)

C.’ Purity: Moral Codes (Leviticus 17–20)

B.’ Priesthood: Maintenance of Holiness (Leviticus 21–22)

A.’ Ritual: Sanctifying Time: Feasts & Things (Leviticus 23–25)Epilogue: A Call to Covenant Faithfulness (Leviticus 26–27)

There are three solutions to the problem: the ritual (A), priestly (B), and purity systems (C). Each “solution” is handled in two corresponding sections. The whole thing is centered around the ritual of the Day of Atonement—the holiest day in the Jewish year—when the High Priest sanctifies the whole nation and the Holy of Holies.

You might think of all of this as the LORD’s gracious concession to human sin. The elaborate system of sacrifices and ritual cleansing is established by God to allow impurity and sin to be dealt with in a meaningful way. It’s a set of symbolic actions that show how God will make his people pure and clean so they can dwell with him. When his people enter into these actions and go through the rituals, we embody them in faith. These rituals are not magic—they don’t work on their own apart from faith and apart from God’s grace. They are a symbolic system in the embodied world that the LORD has blessed and established as a gift so that he can dwell with Israel (Lev 17:11; cf. Heb 9:11–14; 10:1–10).

Remember, that the book of Leviticus is part of a story. Israel arrives at Mt. Sinai in Exodus 19 and remains there until Numbers 10. This comprises fifty-eight chapters (31%) of the Pentateuch and a full year of these people’s lives. The center chunk of that material is Leviticus. It isn’t just a sacrificial handbook—these rituals move the plot forward.

At the end of the book of Exodus after the Tabernacle is completed, Moses is not able to enter the tent to meet with God because God’s glory—his holiness—is there (Exod 40:35). Four verses later, in Lev 1:1, God calls to Moses from inside the Tabernacle. Then we read all the laws and provisions of Leviticus, which conclude with these words:

Lev 27:34

These are the commandments that the Lord commanded Moses for the people of Israel on Mount Sinai.

Now read across the page to the very next verse.

Num 1:1 (cf. 7:89)

The Lord spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai, in the tent of meeting […] after they had come out of the land of Egypt.

The difference between “from” in Lev 1:1 and “in” in Num 1:1 is a subtle but clear distinction in the Hebrew. Moses can now enter into the LORD’s presence. What this shows is that the book of Leviticus works. Through the ritual system of Leviticus, the holy LORD can dwell in the midst of his people, “tabernacling” with them as John 1:14 says. The LORD accomplishes what he commands (Heb 10:19–23).

LORD, give us a deep reverence for you and your holiness. May we be properly disgusted by sin and death. Draw us toward you. Help us to reflect your character in all we do—how we speak, how we work, how we dress, how we eat, how we worship. Rest us in the confidence that you have made and are making us holy in Christ. Bring us to live with you.

No. 8 (1952) by Mark Rothko, image from wikiart.org.

Pray With Us

- Pray for the students in Liberia who are coming to my course on Proverbs. Pray that this material will connect to their hearts, show them the Wisdom of Christ, and help them to live a richer and truer version of the Christian life. Pray for their health and safety as well as the provisions that will allow them to study. May they bless Liberia and West Africa with the gospel for years to come.

- Pray likewise for the students at William Tennent School of Theology. Pray that they too would be kept safe and that their hearts and minds would be deepened by their training. Help them find the balance and grace they need to study well amidst the vagaries of life.

- Please continue to pray for all my upcoming travel. There are still so many contingencies. After the last couple years, it seems hard to imagine it will all work out.

- Pray for Meghan and the girls on the home front. My travel places an extra strain and burden on them. Give them grace and the needed provisions and support.

- Pray for my time at Oxford, that it would open the right doors for future collaboration and ministry.

Notes:

Levine, Baruch A. JPS Torah Commentary: Leviticus (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989).