The Freedom to Make Mistakes

Happy Monday, if there is such a thing, and welcome back to Productivity, Without Privilege. I’m your inbox harbinger, newsletter companion, and erstwhile friend, Alan Henry, and hopefully this week I can get back to offering you some tangible tips and suggestions to make your work and your workplace a more inclusive, effective place.

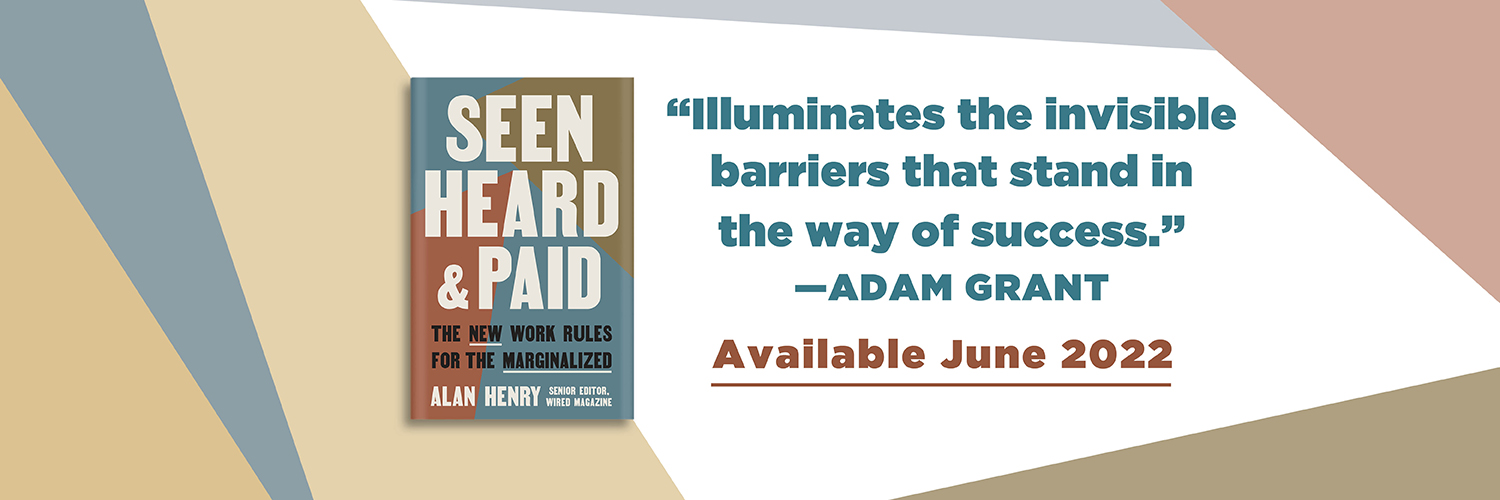

Before I get started though, of course I have to ask if you’ve ordered your own copy of Seen, Heard, and Paid: The New Work Rules for the Marginalized, available now wherever books are sold! (I love being able to say that.) If you’d like a signed copy, The Strand bookstore here in New York City still has a couple in stock, shipping nationwide! And for all of you who have bought the book, reviewed it, encouraged other people to buy it, and shared your book photos with me, thank you so, so very much. It’s been a month since the book came out, and I’m still doing podcasts and media appearances to promote it, and I couldn’t be happier.

So, looking back over the past few months and thinking about how many times we’ve had to shift gears because something awful or noteworthy happened is a little demoralizing. So this week I want to talk about something important based on a conversation I had on a podcast (which isn’t out yet, I’ll let you know when it is!) recently: the importance of being able to make mistakes.

On the podcast, this was about how important it is to be able to make mistakes and learn when it comes to being an ally. We also discussed being able to create space for others to make mistakes and grow, but also to accept that you or I, who need to recognize our own priivlege, whatever privilege that may be, to make mistakes and learn from others without feeling like we’re being attacked (even when we are being attacked.)

For example, I identify as cisgender and male, which gives me a certain privilege as I move through the world that people who identify as female or non-binary don’t have. It puts me in a position of social power where I don’t necessarily need to think about the implications of my gender on, for example, whether someone will promote me, or whether someone in my company is wondering when I’m going to get pregnant and take months of maternity leave off work. It puts me in a position where I need to actively recognize the potential danger I pose to others, just by virtue of, for example, the fact that statistically the biggest danger to women is, categorically, men.

But being aware of one’s privilege isn’t enough, frankly. You also need to be aware of how you engage with others on the topic of your privilege, and do the work necessary to make sure that the people who are wary of your privilege understand that they’re safe around you, that you understand your privilege and their need for safety (both psychologically and physically), and you need to do so without centering yourself. That can be a tall order for someone who’s never processed their own privilege, or who doesn’t have some intersectional understanding of what privilege really is.

This means that while I can read my friends on Twitter talk about men in general without taking offense or—even worse—jumping into the conversation to say “well I’m not like that” or “not ALL men,” some people just can’t resist. After all, my femme friends on Twitter have no idea whether I am or am not the kind of man they need to be afraid of, and me simply screaming at them that they don’t have to fear me is…exactly the kind of behavior that would make someone fear you. When I complain about white people on Twitter, if someone comes in to lecture me on the notion that talking about racism is the real reason people are racist, I know immediately that I can’t trust that person to hold my spot in line, let alone respect my human rights and personal autonomy.

And while the real challenge there is to sift between a person who’s saying that because they don’t know better versus someone who’s doing it in bad faith (and honestly, on social media, it’s probably bad faith) we do need to make room for both a: the marginalized person’s need to express their anger, frustration, sadness, and righteous fury, and also b: the privileged person’s worry that they’re being unfairly targeted—which is really just their own gap of knowledge between who they are personally and who they are as a social group.

Making room for those people to make mistakes is surprisingly easy, although it’s extremely difficult depending on the medium. In-person, and in smaller group conversations, I like to take pages out of Kevin Nadal’s microaggressions handbook, where you make sure to focus on the person’s action instead of the person themselves. So for example, because socially we understand that being racist, misogynist, homophobic, transphobic, antisemitic, or islamophobic is wrong, point out that the action, not the person is one of those things, and of course the person making the comment wouldn’t want to be considered that kind of person, right? That, for one, has never failed me.

Jay Smooth also made an amazing video about this several years ago (and continued the point in this amazing TED Talk) that I still link to people whenever I can, especially to marginalized people who will, inevitably, be in a position at some point of having to explain to someone they know or otherwise like that something they did or said is problematic. J. Smooth also

A lot of it is a natural rebuttal to the notion that because you did something wrong you must be a bad person—or because you hold a problematic belief that you must be a problematic person on the whole. No, you’re just a person with problematic beliefs, and beliefs—just as they’re taught to you—can be corrected.

I feel like this conversation ends up unfairly reductive, especially on social media, where it’s often easier to double down and defend yourself against any perceived threat than it is to engage in good faith with someone. I also think that social media does, in some ways, function far better as a place to listen to the righteous rage and sorrow of marginalized people than it is a place to dissect that rage or for privileged people to attempt to understand that rage. That’s why I am never surprised (and you shouldn’t be either) when someone rages about transphobia, for example, and when someone comes into their replies to question the nuance of that transphobia, or the circumstances around it, or the heart of the person who committed the offense, or anything like that, I roll my eyes.

This all also comes with the fundamental understanding that everyone here is behaving in good faith and with the desire to truly do the right thing. There are plenty of privileged people who are more than happy to punch down loudly and publicly, and then hide behind a progressive posture when they’re called out on their behavior, and there are also marginalized people who thrive on punching down on other marginalized people because it offers even the smallest semblance of control—especially when punching up is difficult and feels like you’re punching a brick wall that won’t yield and won’t listen to you (and that’s not an excuse, even if it is an explanation.)

We’re on the edges of that kind of understanding of social media, but the real point here is that it’s not an ideal place to broadcast your lack of understanding to the world. In order to make space for yourself—and for others—to learn from each others’ lived experienced, the key is to interrogate one another’s opinions and biases in safe spaces. And it’s on all of us, both marginalized and privileged alike, to create those safe spaces where we can come, learn from one another, and allow ourselves room to grow and be educated by one another without feeling like learning from our friends is the same thing as being attacked by our enemies. Because after all, we are in this together.

[Worth Reading]

Intersectionality, explained: meet Kimberlé Crenshaw, by Jane Coaston: When I was looking for a good reference to discuss intersectionality, both in a previous newsletter and above, I kept stumbling on this amazing interview with the woman who coined the term intersectionality, and this excellent dissection of why conservative people are so terrified of the term, and of what it means. But beyond all of that, it’s wonderful to hear in Crenshaw’s own words why the concept is so important to social justice today, and why intersectionality really does factor into the social systems that keep marginalized people of all identities and groups sidelined.

How the end of Roe could affect abortion access in Latin America, by Kenichi Serino: Kenichi is a friend, and this story is incredible. So often Americans tend to point to other countries around the world that we’re supposed to be “superior to” as examples of places that are supposedly backwards that also get things right that we don’t, and forget that the struggle for human rights and liberties is a global struggle. The forces of oppression here in the United States have no qualms borrowing from the playbooks of despots and hate groups around the world, and they have no problems exporting their own techniques elsewhere, and we’re already beginning to see that take shape in Latin American countries, where women’s rights are and remain tenuous.

Hoochie daddy shorts give more than a 'lil leg; plus let's get Seen, Heard and Paid: Am I cheating again? Yes. Do I make the rules? Also yes. This is this week’s episode of NPR’s It’s Been a Minute, where I had the pleasure of sitting down with host Anna Sale to discuss my book and what I hope people take away from it. I didn’t get a chance to talk to Danez Smith about hoochie daddy shorts, but given how that part of the interview went, I might consider a pair. Either way, take a listen if you don’t already subscribe to the show, and let me know what you think!

[See You, Space Cowboy]

If you’re a video gamer like I am, or if you know someone who is in your life, this bundle over at itch.io is for you: it’s the Worthy of Better, Stronger Together for Reproductive Rights, where all proceeds will be split 50/50 between the National Organization for Women and the Center for Reproductive Rights.

The bundle includes 169 games (that’s right, one hundred and sixty-nine games) including bangers like the eldritch horror dating sim Sucker for Love (which I actually love, despite its Lovecraftian roots) and Catlateral Damage, where you, predictably, play a cat that needs to manage its owner by doing cat things—like knocking things off of shelves. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The whole bundle will set you back ten bucks (yes, $10 USD for that many games!) and is more than worth it on its face, not even counting the fact that every cent goes to worthy causes.

When you get this, the bundle should be available for a few more days, so go ahead and grab it! Then let me know what you’re excited to play, and maybe I’ll play it as well!

Now then, have a wonderful week, and I'll see you back here in two.