Do Not Trust "Helpers" Who Don’t Know What You Do

A few weeks ago, I spent a week in Europe, my first time traveling internationally in about a decade (although I’ve done a lot of domestic travel in the interim). I wish I could say the trip was for pleasure, but no, it was a work trip. That said, I had an incredible time and came back feeling changed. In a way, spending a little time abroad reminded me that this sense of madness we’re struggling to navigate here in the United States is truly an American problem, not a global one.

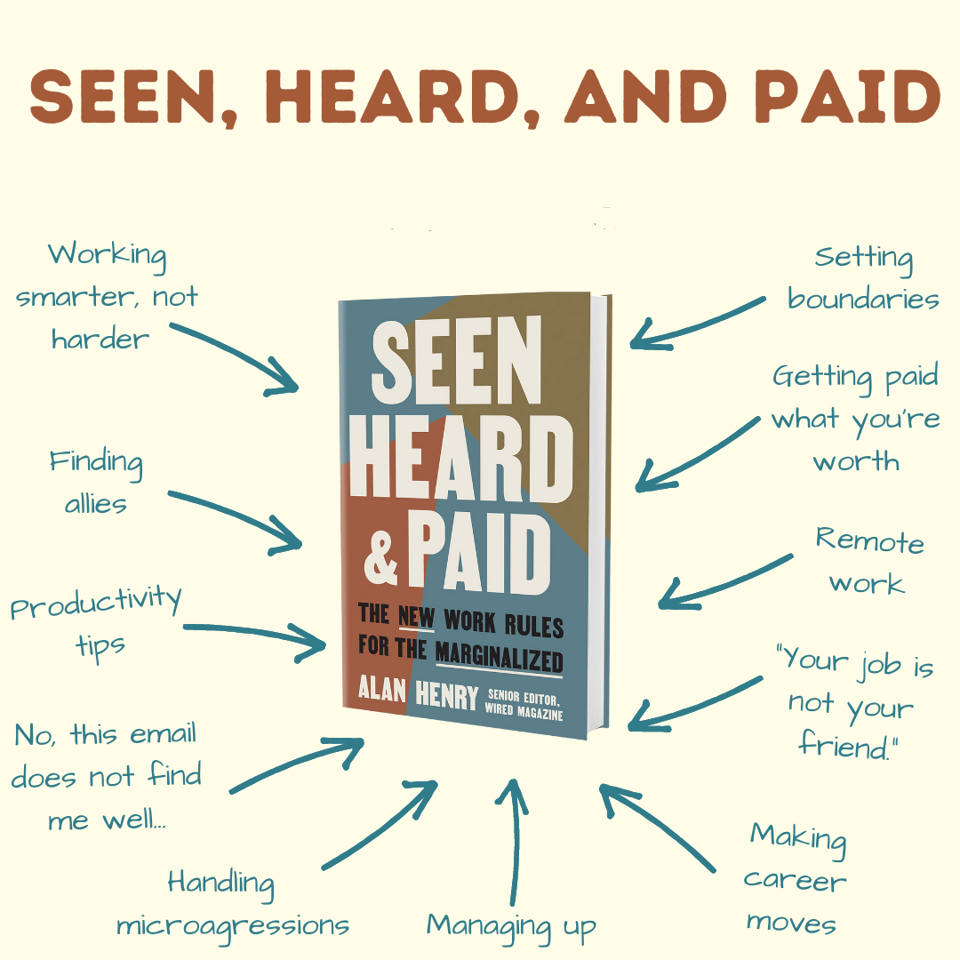

Hi! I’m Alan Henry, author of Seen, Heard, and Paid: The New Work Rules for the Marginalized, and your humble host this evening. Make sure to tip your server, and do order the mac and cheese, it’s excellent here. Let’s get into it, shall we?

***

I want to talk about what happens when you take risks, and how easily reward can come to you if you’re open-minded about those risks. And of course, what happens when people take risks with closed minds, and the havoc that can result from their actions.

My trip to Europe came together uncomfortably quickly, and it was very much a work trip, where I met with a couple of companies my team at PCMag covers. Don’t get me wrong: It was great, the days were packed with interesting meetings full of people doing interesting things, but I don’t think I can explain how nervous I was beforehand. Part of it was because I would be traveling alone, so far from home, for the first time in ages, but also because the current political situation here in the United States made me incredibly worried about what coming home would be like, and whether my role as a journalist would mean extra questioning, seizure of my devices, or worse.

After some hardening of my devices before I left (and while I was abroad) and some encrypted backups, the trip there and home were all fine. Customs both in the EU and back here in the US were appropriately grumpy, as I expected them to be, and I won’t say I had nothing to worry about. Still, I’m glad I prepared (and I would recommend anyone else planning international travel do the same). But the real lesson from all of this is that everyone I met in both countries I visited all had the same question for me: “What the hell is going on in the States?” To which, of course, I can only answer with “I wish I could explain logically, but what’s happening right now has nothing to do with logic or facts or truth.” To which everyone immediately understood.

I explained systemic racism to a Lithuanian woman who got it and understood what I was talking about better than many white Americans I’ve met.

Most people in many other countries know intimately what it’s like to be neighbors with people they either don’t get along well with or haven’t gotten along well with historically, even if things are okay now. So when I explain to them that we live in a fiercely individualistic society where fear and hatred can win over justice and equality if the messaging strokes the right egos, they get it.

And boy, did they get it. And my reward for opening up was stories that reminded me that we’re all human and alike in the ways that matter, even though we have a lot of work to do both at home and abroad to make the world a better place.

I came back with a deeper understanding of some cultures I’d never been exposed to, and I got to see a city I lived in when I was single-digits years old before jetting off to another city that I hadn’t seen since I was single-digits years old. I saw the care and beauty of some places that care about their citizens more than real estate developers or high-end investors. I saw people working at companies where, sure, they’re there to make their business as successful as possible, but also showed care and consideration for their communities that I don’t see in, for example, Silicon Valley.

So I came back from my European jaunt hopeful, thinking about the things I could do, the changes I could make, and how I could get back to my journalism to serve my readers and help people, like I’ve always wanted to do.

But when I returned, I was confronted with my old nemesis, mediocrity. Namely, being forced to suffer the “advice” of people who don’t know, or care to know, what you do or why it works or doesn’t work.

Many years ago, we made a big push for podcasts at a different publication I worked on. At the time, podcasting wasn’t new exactly. Still, many publishers were suddenly interested in investing resources into podcasts because there was hype (and more importantly, potential ad dollars) around them. Popular podcasts had been around for ages, and even the publication I worked on had a podcast we had sunset years prior because we couldn’t get organizational support for it. It was just one more thing for us all to work on that we loved, but couldn’t mesh with our actual responsibilities. So instead of asking anyone who’d worked on it before what they wanted to do and how they wanted to do it, they brought in someone else to tell us all what to do.

That person had no background in podcasting, and had no real direction for us (aside from “try to be like these podcasts that I, personally, like and think are successful,”) and with the blessing of an equally mediocre management team, they set to work pushing back on anything we suggested that might actually resonate with our audience, disrupting our workflow, and essentially making the whole process miserable. The people involved with the entire debacle quickly vanished, failing upward to other roles where they could claim success that they didn’t have anything to do with (at best) or pretending the problem was with those of us on the ground who stood in their way (at worst). One of those people is a very prominent reporter at a well-known publication now, who, again, is probably one of the most abysmal writers on his beat that I’ve ever seen. Another is in charge of another publication, and is just as problematic. Both of them benefit from the same privilege and expectation to comply with their ideas that they would never give to their marginalized colleagues.

Fast forward to now. Looking around the journalism industry, I see the same trends playing out again, because yet again, journalism as a field is under existential threat (although it’s never not been). Again, soothsayers who claim to know what will save you and your publication have plenty of ideas, and most of those ideas have nothing to do with the actual job that you do, but again, chasing the tail of other publications that are weathering the same storm. Sometimes that advice comes in the form of “let’s do what X publication does with their headlines,” or “Google is prioritizing this thing, so we should do it too,” which is especially maddening. Especially considering, and let’s be extremely real here, SEO as a field, aka “letting Google be your editorial director and take assignments from people who aren’t writers or journalists,” is about 40 percent fact and 60 percent fiction, and I’m being very generous.

In short, in Europe, everyone I met explained that the best part of their jobs, and the secret to their success, isn’t to follow their competitors or do what others are doing, but to break off and try new things. To see what their customers need and consider how they can provide it. To experiment, see what works, learn from what doesn’t. I remember when that used to be a guiding principle for writers of all kinds as well: novelists, essayists, poets, and yes, journalists.

When I got home, I looked around my own industry and was reminded that standard practice in many places is to take assignments from people who can’t even pronounce the thing they’re telling you to look into, nor do they have any idea what it is or why it’s important; they just saw it in a report somewhere without context. They’re not even sure if you’ve already looked into it; all they know is what they can divine from the almighty algorithm.

***

So again, I see publications laying off talented writers who could do amazing, incredible things that would resonate with their audiences and bring in new, passionate readers. I see them laying off all of their writers of color, claiming that it’s just “economic headwinds” and that they’ll make it up by plundering those writers’ ideas by forcing them to be freelancers instead, paying them a pittance to open a vein and share their best ideas with a publication that says “thanks, here’s a couple hundred bucks, smell ya later.” At the same time, they quietly remove language about diversity and inclusion from their websites, or worse, champion it publicly but only publish the same types of content we’ve seen for decades from the same faces, when new writers with new ideas are clawing at the doors looking for opportunities to share their stories and their voices.

And those who remain get told that instead of repairing the ship or being thoughtful or innovative, you should try to do what the other sinking ships next to us are doing, even though they’re in the same situation, or worse. Essentially, we all feed on each other’s failures, claiming we want to be better, more useful, essential.

It’s the cult of mediocrity, draped in the trappings of meritocracy.

***

Okay, so if you’ve kept up with me this far, thank you. That’s a lot of complaining about the state of the industry! But there is something you can do about it, and there are ways you can push back against this kind of automating, algorithmizing, factory farming approach to information, entertainment, education, and connection. It comes from my friend Justin Pot, who has a fabulous newsletter of his own that you should subscribe to, but specifically in the edition where he explains that extrinsic motivation is ruining everything for all of us. Instead of us doing things because we want to do them, or because they bring us joy, or because they help us express ourselves or connect with others through storytelling, we’re forced instead to think about them in terms of how we can make money from, profit off of, or potentially use them to survive. And that’s heartbreaking, especially in the age of AI, where the need to monetize everything we do is a poison and usually doesn’t even end up serving us in the way it serves people waiting to prey on our ideas.

You should read those two editions of Justin’s newsletter, but the bottom line is to take time to create things purely because you want to. You don’t have to attribute value to your work—in fact, often the best work is made without intending to be valuable to others. The best stories I’ve read were people writing things I couldn’t read anywhere else, published in places willing to take a chance and say or do something original, insightful, or enlightening. And right now, the bar for those things is on the floor.

And in a way, that’s why so many publications are working so hard to sideline or remove them. There’s little room in mainstream media at this stage for anything else. The goal is to make money, to survive at all costs, to get through another year without getting laid off. At the same time, your CEO spends your salary on fancy lunches, or the company is committed to the most expensive real estate in the hemisphere.

Those outlets, especially under the current political administration in the United States, aren’t interested in the kinds of stories they claimed to be: tons of new voices sharing eye-opening experiences that offer a broader world perspective. Sadly, these days, that appetite has shifted squarely to more non-threatening, mainstream stories that are interesting, but perhaps not insightful. Scoops that are certainly explosive, but without follow-up or analysis that make them anything more than a spike on a pageview chart or a moment in the never-ending news cycle.

***

So while this may not be helpful to someone trying to get a book published, or break into a publication with their first story, or who wants everyone to see their hard work on social media, I implore you to create for the joy and the sake of creating. Tell stories that you know need to be told, even if they don’t get seen by millions of people. Experiment with new ways of sharing those stories and connecting with people who may be interested in them. Start a newsletter (Buttondown, the platform I’m using, is a great option. Here’s a link for $9 off your first month if you need a paid subscription.) or a YouTube channel, not to monetize it, but to speak from your own stage. Start a blog, keep the good stuff off social media, and put it somewhere you can control and enjoy it instead. Build something you’re proud to show others at the end of the world and say, “I made this. I showed the world my soul and am proud of what I did.”

Mainly because the opportunities to do so and survive are becoming rarer and rarer, at least here in the States. I came back from my trip with open invitations to live in three different countries, so maybe moving is an option, too.

[Read This]

What It Means to Tell the Truth About America, by Clint Hill: One of the wildest things about this story, aside from the fact that everything in it is entirely predictable (namely, that the National Museum for African American History and Culture is under attack because it dares to tell the unvarnished truth about American history, even if little Jimmy from North Dakota’s parents have to explain to him that yes, his ancestors did horrible things.) On the one hand, I’m surprised The Atlantic was willing to publish this story, but on the other, I’m glad it’s in such a prominent place. Give it a read and understand exactly what happens when the truth—the objective truth—gets shoved to the side by people who prefer to codify fantasy.

The Rich ‘Take Up Space’, via Freedom News: A lot of things have been written about the PR stunt that was Blue Origin’s trip to near-space featuring an all-female crew, and I’m using the term “crew” extremely lightly, since between Katy Perry and Jeff Bezos’ girlfriend, I don’t think much actual crew-work was conducted on the “rocket goes up, rocket comes back down” trip. My issue, of course, isn’t with the work or even the rocket; it’s with, again, mediocrity. The least qualified and least deserving human beings get the best opportunities simply because of their connections or currency, in whatever form that may take. And now, all of our institutions are being directed to this same mediocrity, turning everything from space itself to the bottoms of our oceans into little more than playgrounds for rich. At the same time, the rest of us suffer to keep them wealthy, as though they’re the only ones who get to truly live.

Font used in famous anti-piracy campaign was pirated, by Rob Beschizza: If you’re even remotely my age, you probably remember “You wouldn’t download a car,” as the RIAA’s attempt to try and convince us that piracy wasn’t cool. (I think “Don’t Copy That Floppy” was far more successful.) Well, it turns out that the font used in that iconic image was itself pirated from its source, and the music used as the background for the ad was also pirated. But of course, companies never think that they can pirate things from others; they see themselves as the only holders of value worth extracting, and that nothing anyone else has done could have value, even if those companies want it. Anyway, the story is hilarious, and a refreshing cap on a lot of awful other news.

[Try This]

A few of my friends have been talking about Too Good to Go for a while, and while I hedge at any product or service that claims to encourage social good and community action through consumption, I vibe with the idea of showing up at a restaurant early in the morning, after dinner, or before closing to score some cheap (or free!) food items that would otherwise get wasted. So I’ve been giving it a try - there are a few spots near me that seem like good options, and I was surprised when I signed up (email address only, no password required) that there was so much in my area, even though I live in New York City.

Granted, your mileage will vary depending on where you are in the world, and honestly, if you do have a relationship with a local business already, that’s way better than using an app as an intermediary. But it's worth a look if you don’t have those relationships or want to discover some new ones you can build those relationships with. Check it out first to make sure it’s useful for you, obviously, and steer clear of (unless you want them, I suppose!) the ones that are essentially little more than lunch or dinner specials instead of food that may actually be wasted.

***

That’s it from me for the time being. Take care of yourselves and your loved ones in this strange and difficult time, and I’ll see you back here soon.