Digital Sight Management, and the Mystery of the Missing Amazon Receipts

Hello new subscribers! Thank you for joining my newsletter, which as promised, will be updated very infrequently.

And hello old subscribers! If you haven’t already seen it, check out my recent blog post, What ARGs Can Teach Us About QAnon which went extremely viral, got republished on Vice, and landed me an interview on the New York Times.

Phew. What a month. What a year.

I haven’t been writing much on my blog recently, mostly due to pandemic reasons, but also because I’ve been working on my gamification book. I finished a 16,000-word book proposal recently and it’s floating around the publishing world as we speak.

Anyway, something between the book proposal and the QAnon piece loosened up my blog posting muscles, so here is my latest piece, also on my blog:

Digital Sight Management, and the Mystery of the Missing Amazon Receipts

Chances are you’ve bought something from Amazon in the last few months (yes, we are all hypocrites, also there’s a pandemic on). Try searching your email for one of those orders. For me, that’d be “cat flap” or “chilli oil” or “airfloss”.

No luck? You aren’t alone: Amazon stopped including item details in order confirmation and shipping notification emails a few months ago. They just show the price and order date now. For all its faults, Amazon has pretty good customer service, which makes this user-hostile change baffling to understand. Sure, you can still see your orders on Amazon’s website and download a CSV, but it’s far more cumbersome than searching your email; and if you’re a power-user, you can say goodbye to automatically generating to-do tasks from Amazon emails.

What reason would be big enough for Amazon to annoy so many of their users? It’s simple: data.

Popular free email clients like Edison Mail and Cleanfox “scrape” their users’ emails and sell anonymised or pseudonymised data on to third parties. With enough users, they can detect trends and measure brand loyalty – valuable information for competitors. By stripping item details from its emails, Amazon tells us just how much this was hurting them.

Then again, Amazon knows the value of data. It’s been accused of competing with its own Amazon Web Services (AWS) customers by watching their usage:

Critics argue that the company’s role as a platform gives it an unfair advantage. Because AWS has thousands of customers, the company has a godlike perspective of broad industry trends, including insight into which third-party tools are most popular. The suspicion, one executive of an open source cloud tool company told me off the record, is that AWS is watching “run rates” — the amount of money spent on a particular tool per year. When they see a service provider like Elastic start to generate serious revenue, Amazon incorporates the functionality of that tool into its own proprietary service. In the words of Warren, that makes AWS both a team owner and an umpire.

And it’s also used the private data of third-party vendors to launch competing products:

Amazon employees accessed documents and data about a bestselling car-trunk organizer sold by a third-party vendor. The information included total sales, how much the vendor paid Amazon for marketing and shipping, and how much Amazon made on each sale. Amazon’s private-label arm later introduced its own car-trunk organizers.

For Amazon, turnabout isn’t fair play, but unlike companies who have little choice but to use AWS or sell on Amazon.com, it can solve its problem by tweaking the emails it sends to customers. For now.

A couple of years ago, I had a long call with Samsung’s Global Strategy Group about using gamification to sell heads-up displays and augmented reality (AR) glasses. It’s an open secret that every major tech company thinks AR glasses are the Next Big Thing after smartphones, so their interest wasn’t a surprise. I told them most gamification was awful and ineffective, but it was fascinating to see Samsung casting about for ideas, as if unsure what people would use AR glasses for.

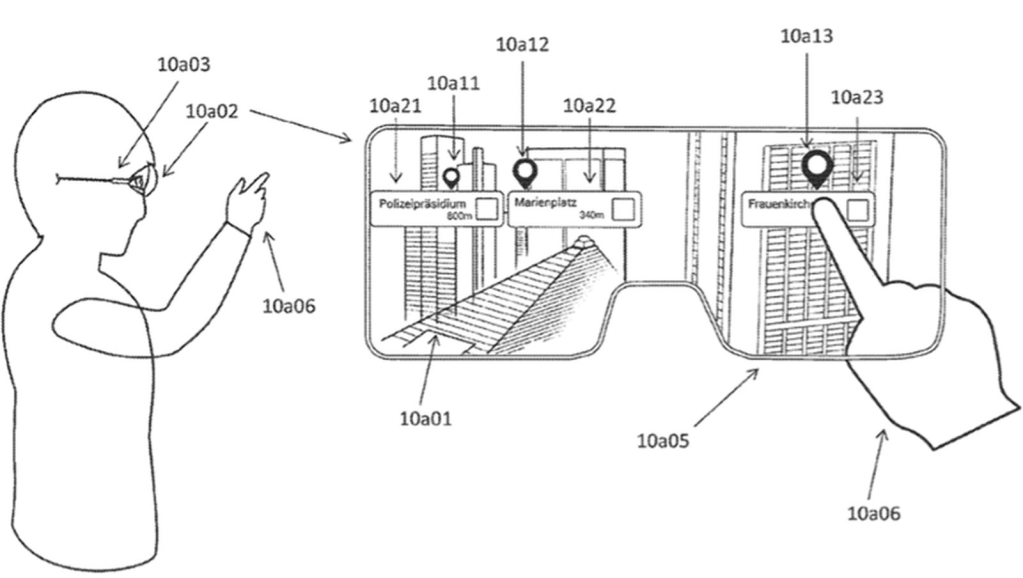

Apple patent 10741181 “User interface for correcting recognition errors”, includes an AR glasses interface

Some applications for AR are obvious in the same way that web browsing and music were obvious for smartphones. We can all agree it’d be helpful to see directions hovering over streets rather than peering down at a phone; to visualise how to repair a broken coffee machine without flipping through a manual; and if you’re like me, to see people’s names floating beside their heads at parties. But smartphones changed the world far more dramatically in ways that most people didn’t predict, like social networks, taxis, photography, games, retail, and fitness.

It’s a fool’s errand to imagine every use of AR before we have the hardware in our hands, yet there’s one use of AR glasses that few are talking about but will be world-changing: scraping data from everything we see.

Take the example of Amazon’s emails. What if customers start wearing AR glasses that use computer vision to recognise everything they see – not just acquaintances’ faces but the checkout screens on their phones and laptops? What if it’s possible for other companies to scrape customers’ every interaction with Amazon, from their search terms to their eye gaze as they scan through the options, to the reviews they read and the other stores they’re visiting?

What’s true for Amazon is true for every other tech giant that jealously guards the data it “owns”. In just a few year’s time, augmented reality open a new war between those who hold data and those who want it, and it’ll be the war to end all wars. AR glasses will enable the collection and processing of information about our lives and the entire world in a way that’s so powerful, tech giants will feel they have no choice but to lock AR hardware down tight – so tight that in a decade’s time, their considerable control over our lives today will seem laughably laissez-faire.

Because what will it mean when everything can be scraped?

Worldscraping

With hundreds of millions of users, MyFitnessPal is the most popular calorie counting app in the world. One reason why it succeeded is because it had the most complete food database. It was too expensive and time-consuming to get nutrition data from manufacturers, so they crowdsourced it:

[Founder Mike Lee] realized that MyFitnessPal would only truly scale if he called on his users to help [populate its food database] — in other words, crowdsourced it by enabling MyFitnessPal’s users to input and check data. The alternatives were to get the data from open food nutrition databases or directly pipe it from food manufacturers. However, there wasn’t a comprehensive open database of barcodes that MyFitnessPal could tap into and getting the data from food manufacturers was far too much work. Besides, if their own users entered the data then MyFitnessPal would own it. One of the defining characteristics of so-called “social” software — like Facebook and Twitter — is that the value of the business is almost all derived from the amount and quality of user data in its databases. MyFitnessPal is no exception, so Mike Lee was very smart to go the crowdsourcing route. Everything its users enter into MyFitnessPal’s food database belongs to MyFitnessPal.

MyFitnessPal’s economic moat was, and still is, its food database. Like so many other “web 2.0” and early smartphone apps (Foursquare, Google Maps, Yelp, TripAdvisor, Waze, etc.) it exploited and gamified users’ labour to amass data that would otherwise be prohibitively difficult to collect. Now they own that data, it’s nearly impossible for competitors to catch up – what community will put in the million hours required to reconstruct MyFitnessPal’s food database when they could just… use MyFitnessPal?

Foodnoms AR nutrition label scanning via Macstories.net

Augmented reality threatens to upend that equation. Apple’s ARKit frameworkhas made it possible for solo developers to create apps that use your iPhone’s camera to instantly recognise and parse nutrition labels, vastly reducing the effort required to populate a food database. In principle, you could just as easily point your phone at a restaurant menu or a supermarket aisle or, why not, an Amazon checkout page, or any other kind of structured visual information, and it would be similarly parsed.

The only problem is that no-one really wants to pull out their phone and take pictures every five minutes. But if your camera was on your glasses, it’d be no extra effort at all. Apps will passively hoover up this data throughout the day, at a greater speed and likely greater accuracy than inputting the data by hand. There’ll need to photo your Amazon checkout if your glasses are watching all the time. And imagine strolling down a supermarket aisle with a price-comparison AR app that shows you the best deals – while at the same time silently counting the store’s inventory.

Google’s On-device Supermarket Product Recognition demo

Let’s call it worldscraping. It’s not hard to think of applications: archiving every word of every article and book you read for searching later, cataloging the movies and TV shows you’ve watched, saving interesting outfits and clothes you notice in shops or on passers-by, mapping your social graph based on the people you talk to on social media and in the real world, recording your cycle into work in case you get into accidents, and on and on…

Of course, if no-one fancies wearing an always-on camera on your face, this is all dead in the water. But I suspect people will find the lure of AR directions and nametags and translations and instruction manuals and social media and games far too entertaining and useful to pass up, and all of these things will require that camera to be on.

That said, an always-on AR camera doesn’t necessarily have to violate anyone’s privacy. Software can understand and extract salient features from the world without needing direct access to a camera feed; the processing can be done on the device rather than in the cloud; and the collected data could be properly anonymised before being shared. The point is that AR glasses and worldscraping don’t inevitably lead to a surveillance or privacy apocalypse, providing we have serious legislation and regulation.

So: worldscraping AR glasses pose an existential threat to companies whose business and continued existence is based on proprietary data that’s been painstaking collected, crowdsourced, purchased, or in some cases, stolen. And that’s a lot of companies, including, of course, Amazon.

Which means they’re very motivated to kill that threat.

The Big Get Bigger

In 2014, my team at Six to Start worked hard with Google’s developers to get Zombies, Run! ready for the UK launch of Google Glass. We only just made it because, as we all know now, the Glass hardware and operating system was an utter abomination. While Google Glass lives on today as an Enterprise Edition, no-one believes this particular breed of AR glasses will ever make it into the mainstream.

Three years later, I tried out Microsoft’s Hololens, courtesy of a demo by Joshua Walton, its Principal Interaction Designer. Hololens was much better than Google Glass with a wider field of view and more intuitive hand-tracking input, but still generations behind the svelte AR glasses we’d all like.

And a year after that, in a back room at the XOXO festival, I slipped on the Magic Leap One headset. Despite the company having raised over $2 billion, it was slow, prone to overheating, and nowhere near the visual quality in its sizzle reels.

All three headsets failed to live up to their hype, but two will keep going until they get it right, and one of them – Magic Leap – almost certainly won’t. Magic Leap’s single-digit billions, admittedly misspent, wasn’t enough to make the cutting-edge sensors, displays, and processors available at a consumer price, or to write a whole new AR operating system. The ante for that kind of game runs into the tens or hundreds of billions, a price only a few can afford: Microsoft, Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Samsung, and Huawei, all of whom will be investing billions into AR.

So, the tech companies that dominate our lives today are the same that are most likely to manufacture the next generation of essential consumer technology. But we’ve always had big tech companies, right? Today it’s Apple, yesterday it was Dell, before that, IBM. The difference is that today, these companies don’t just want to sell us hardware. They don’t even want to just sell us their own software and content – they want to take a cut from_all_software and content that exists on their hardware, and control it, to boot.

Given that the smartphone market is akin to a natural monopoly (no-one wants to use, let alone carry, two smartphones at once) with high switching costs due to platform-locked personal data, previously purchased apps, iMessage, etc., a state of affairs that has been very profitable for Apple and Google, it’s hard to see the AR glasses market from turning out any differently.

What’s more, the giants who’ll make our AR glasses can’t permit the threat to their business models that worldscraping poses – or rather, worldscraping they don’t authorise. Clearly Google would be delighted for its users to crowdsource even more maps data for them via AR glasses, but they’d be less impressed with people using their hardware and OS to build a competing system. Similarly, Amazon won’t enjoy users assembling a better Goodreads by simply looking at their bookshelves.

They certainly wouldn’t appreciate Kindle users ripping their ebooks just by, well, reading them: you can copy-protect a Kindle file, but you can’t copy-protect the pixels on a tablet screen. That’s the point of worldscraping – anything you can see can be scraped with AR glasses.

Well, not_quite_everything: AR glasses wouldn’t be able to scrape whatever’s displayed on the glasses themselves. So if you sell someone an ebook and you really didn’t want its contents to be scraped, you’d only display it in augmented reality. The same goes for any other content or data you don’t want scraped: just force people to view it in their AR glasses rather than on phone or tablet screens.

Like HDCP for your eyes, companies could refuse to display any valuable data or content on displays other than AR glasses.

It’s For Your Own Good

How to defend the indefensible? Easy: terrify your users.

Tech giants will tout the awesome power of AR glasses while also warning that such power is easily abused. Imagine installing a malicious AR app that secretly recorded everything you saw! It’s enough to scare anyone into a walled garden of apps blessed by Apple or Google or Facebook, the only companies big enough to stand up to your choice of adversary, whether that’s organised crime, Russian hackers, or the Chinese military. Countless companies will want to use AR glasses to cut costs and increase productivity, but they’ll also want to reduce the risk of their data being scraped by hackers.

The tech giants’ War on Terror is working: the Epic vs. Apple/Google fight has seen the same ahistorical arguments trotted out the giants’ supporters, that without Apple and Google’s oversight, our phones would be infested with viruses and malware. This ignores our past, which saw the PC and internet revolutions boom due to the fact that you didn’t need anyone’s permission to write software or create a website; and even worse, it ignores our lived reality, where anyone can install any app on their Mac or PC.

It would be one thing if Apple and Google’s walled garden only kept out genuinely harmful software, as Apple does on the Mac, but their control extends to censorship of serious games about worker exploitation and the effective banning of entire businesses like ebook publishing and game streaming.

These companies treat phones like appliances rather than general purpose computers. Why would we expect Apple or Google or Facebook or Amazon to do any different for AR glasses?

There Is An Alternative

Worldscraping has incredible potential. We’ll be able to extract our own data without needing Amazon or Google’s permission. We can make a better food database, a better catalogue of plants and wildlife, a better map of the world, anything you can imagine that requires information about the real world, all with far less work and in far less time.

The big losers from worldscraping will be incumbent companies and tech giants. They’ll want to keep worldscraping for themselves, and they’ll say it’s because only they can be trusted to use it.

But they aren’t the only ones who can keep us safe. There are ways to secure computing devices without unaccountable gatekeepers or expert users. Contrary to what Apple would have you believe, we all use software every day that’s as safe as anything inside their walled garden, if not safer. We need to support and learn from those third-party companies and open source communities as we head into the next generation of computing devices.

There’s a place for the tech giants in this new world, if they’ll take it. Helping users block malicious software – as Apple does on the Mac – doesn’t require a suffocating grip on software distribution. And they can still make tens of billions a year from selling hardware and their own services. That wouldn’t be so bad, would it?

Google Glass was a joke. Augmented reality isn’t. We can’t just laugh at it or ignore it. That’s what we did with smartphones and social networks, and now we have genocides and anticompetitive corporate behaviour on a global scale.

We won’t be able to opt out from wearing AR glasses in 2035 any more than we can opt out of owning a smartphones today. Billions have no choice but to use smartphones for basic tasks like education, banking, communication, and accessing government services. In just a few year’s time, AR glasses do the same, but faster and better. They’ll also do entirely new and incredibly powerful things, like worldscraping. The danger is that the companies who’ll be threatened by worldscraping are the ones who’ll control the technology that enables it.

We need AR glasses to be treated as the incredibly powerful general purpose computers they will surely become, which means open access for all users and all developers. If tech giants won’t do that voluntarily, they need to be forced to do so by governments.

The alternative is unthinkable: a world where what we see and where we see it is controlled by tech giants.