Strange Animals / 2023 / #4: Learning Is Juggling

Here we are again, one month from the middle of the year. Time. What a twat.

///

May was the busiest month of this year for me. It usually is. A couple of years ago, I noticed that May-July is the busiest time of the year for comics work, and December-January is the sparsest (although you do have to fit a month’s work into the first couple of weeks of December, because the presses need to close for the year, which means hitting some tight deadlines).

The usual trend continued, but I was glad to see that my “busy” month this year meant 120 pages, against the last few years, where it meant 250-400 pages.

I also lettered all of 37 pages last month, which was nice. (My two DC Pride stories, one short that I wrote and lettered that should be announced soon – my first writing work at DC – and preview pages for a 2024 OGN.) Of these, in particular, I got to take more than a week on the Multiversity story, which I feel shows in the final comic, simply because of the time I could spend doing research and fine-tuning my decisions.

As I continue to maintain this slower working pace, I get to see all the invisible work one is doing around the actual work, something that is easy to overlook when you’re busy. Revising, scheduling, prepping scripts, compiling and delivering final files, sending emails, invoicing, taxes, following up on unpaid invoices. All of it adds up to a lot more than one might think. Some overhead is essential, but much of it isn’t adding up to productive work.

I wrote in a previous edition how my big revelation that I needed to cut down on pages came from counting my daily work hours and realising I was spending little more than half my time lettering, and the remaining half with everything else, which was why I was spending 12-13 hours every day working on stuff that seemed like it should only take about 6-8.

So first of all, I cut down on the sheer number of pages. Second, I spent time organising my workflow as well as I possibly could. And finally, I tracked which books/clients cost me the highest number of man-hours in revisions/busy-work, and either worked out more efficient processes with them, or dropped them if I felt it wasn’t worth the extra work.

It’s not just about how much I was getting paid for each hour I was spending, it was about how well I felt my time was being used. If you’re in control of your time, then even time wasted is time well-wasted. If someone else is always in control of your time, then the most productive work can feel like a drudge.

///

Work-wise, last month saw the release of w0rldtr33 #1 after some printing hiccups. This is a very special book to me, as I’ve noted in previous editions, and we’re very happy with the response. w0rldtr33 #2 dropped this week, and has received a great response so far.

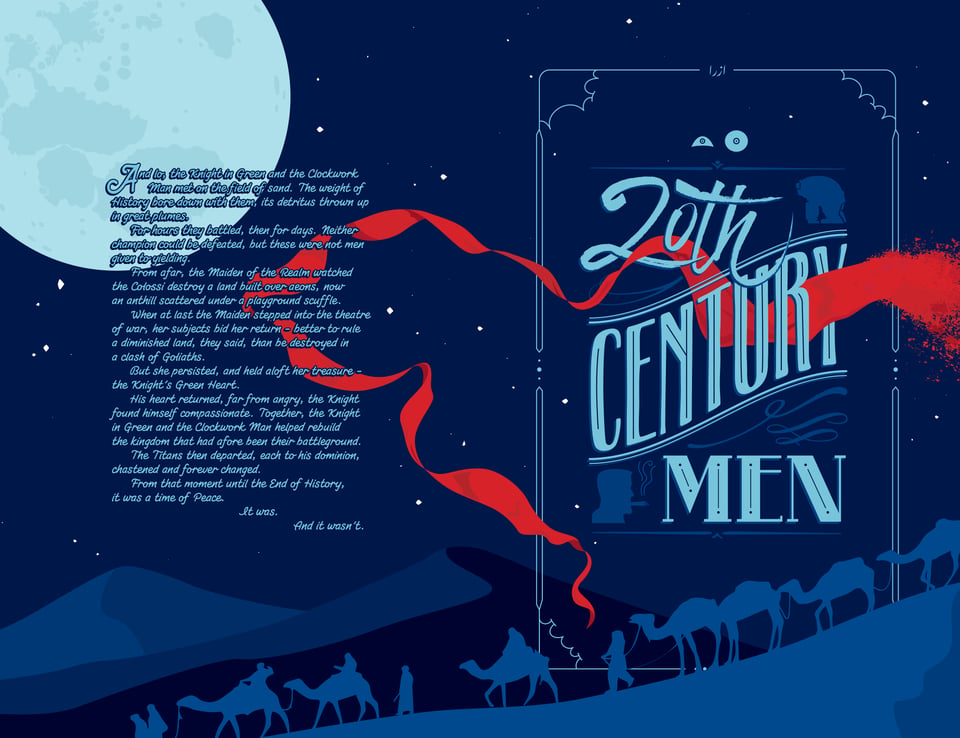

Last week, the collected edition of 20th Century Men was released. It’s a hefty beast, with nearly 300 pages of story that we’ve been working on since before the pandemic. The backmatter also includes my variant cover for the final issue, which I can show you here now in its full wraparound glory:

Finally, DC Pride 2023 was released, for which I lettered two stories:

“Subspace Transmission” by A. L. Kaplan features Circuit Breaker, DC’s first superhero who is a trans man. Circuit Breaker made his debut in Lazarus Planet: Dark Fate, which was lettered by my pal Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou, so I had the fun task of picking up the baton on the style he’d created.

“Love’s Lightning Heart” by Grant Morrison, Hayden Sherman and Marissa Louise is a return to Morrison’s The Multiversity for a wonderful Pride-themed love story. For this, as I mentioned above, I got the time to read all of The Multiversity and much of Morrison’s later DC work (plus the books they referenced in their dense script) to pull out themes and styles I could be inspired by. I also looked back at the Silver Age and Bronze Age stories both Morrison and Sherman were influenced by. In addition, Marissa and I jammed on the titles & credits pane, and she shared the colour palette she was working with early on so I could fit my lettering to what she was doing. All in all, an incredibly collaborative experience, and one of my highlights at DC.

Thanks to editors Jessica Chen and Andrea Shea for inviting me along once again.

///

The big difference in learning something new as a kid vs. learning as an adult is that as an adult, you know when you’re shit. So a kid can make something and keep going, keep making things, because they think what they’ve made is fine. You, the adult who’s trying to pick up a new skill, will quickly hit up against the limits of your talent. And it will sting.

There’s the famous Ira Glass video about taste vs. talent that articulates a part of this. Learning something as an adult is difficult because you have taste, which is a double-edged sword. The solution is, of course, simple – just keep doing it till you get better.

But simple isn’t the same as easy. A child will only realise they used to be bad at something when they look back years later. But you, the adult, who decided to learn something new because you love it, will immediately realise that you’re bad, and will want to quit, because being bad at something doesn’t feel good.

Adulthood, if we’re honest, is a wasteland of people “with potential” who couldn’t keep at something because they couldn’t cross that threshold of being bad.

The solution, for me, is not just allowing yourself to fail, but failing with intention – building failure into the process.

This is where the analogy from the title of this post comes in – learning is juggling.

When you’re learning to juggle, you don’t start with five balls at once, you start with two (or maybe one – I don’t know much about juggling). And when you get good at that – when you get to a plateau – you add one more ball.

When you’re adding the new ball, you won’t stay on that plateau – all the balls will come down at once. You will fail, immediately and catastrophically, over and over, till you learn to keep three balls up in the air. And when you get to four, once again, the whole thing collapses for a while.

But the key is – this is the process. You cannot get better without the failure, unless you’re just happy to stay on that first plateau. And you can’t get from one to four directly – you have to fail multiple times.

It took me a while to learn this when I started drawing seriously in 2021. You won’t start off being able to draw the entire figure immediately. If you try, you’ll get proportions wrong, anatomy wrong, foreshortening, and so on.

So I started with gestures – the flow of the drawing. Once I got decent at that, I added anatomy and structure, and everything was terrible for a while. I was producing bad drawings. If I focussed on a beautiful hand, I’d step back and find that I’d placed it on an arm that was too small for it. If I focused on anatomy, the figure would look far too stiff.

This was quite frustrating, because I was able to hold all of these things in my head one at a time – it was when I tried to combine them that things were screwed up.

What was the solution to the juggling problem, then?

I thought back to the last thing I’d learnt to do as an adult, and quite successfully – lettering. I started lettering as a hobby when I was 24 years old, and had no prior design/art experience. About two years after that, I was lettering for a living. How had I done that?

That was when I remembered my lettering checklist. I posted this on my blog some months ago, but this essay was why I’d dug it out in the first place. (Explanations for individual items are in the linked blogpost.)

Ensure correct reading order

Ensure stylesheet consistency

Ensure nothing important is covered

(before and after colours)Check and remove tangents

Avoid action lines

Avoid eye lines

Balloon tails of consistent width

Consistent air around balloon text

Consistent stacking (vertical/horizontal/round)

Tails should point from the centre of the balloon to character’s mouth

Avoid placing balloons over character/BG intersection (particularly for strokeless balloons)

Avoid placing balloons over overlapping planes

Direction of SFX

Ensure SFX colours work with the palette

Keep lettering in engagement zone (ensure nothing’s too far from the page centre to be engaged with)

I’d made this checklist because I had started lettering professionally, but I was still raw enough that I was making mistakes in the flow of things. And now the stakes were high enough that I needed to get things right if I wanted to keep my job.

So I wrote down everything I knew about good lettering, and after I’d done a first draft of any issue, I’d go through every page and inspect it against this list. What that meant is that I didn’t have to remember everything at every moment while I was working. I could get things wrong, and come back to fix them later.

Funnily enough, after a couple of years, I didn’t need this list anymore, because I was doing all of it instinctively. Every time I found a new precept that I agreed with, I’d add it to the list, pay attention to that particular thing for a while, but then it’d get ingrained in me, and it started to come naturally.

Every time, I’d learn to keep one more ball up in the air.

So that’s I had to do with drawing. Add one thing to my arsenal at a time, and every time I did that, prepare for things to go badly for a while, and as I went, make a list of the things I needed to pay attention to, till they became instinctive.

And every time I felt like my drawings were getting bad, I could retreat to doing the things I knew I could do well, to make myself feel better.

Once I built this into the process, the failures got much less frustrating, because not only were they a part of the process, they were essential – they meant that I was doing things right, and trying to reach higher than I was able to go.

Figuring this out also made it easier to move on from bad drawings. It’s hard to feel bad about failure when you know you won’t get anywhere without it, and you slowly start stacking up enough good drawings that the bad ones don’t hurt.

///

This one was difficult to write, because I kept thinking of other things I’d figured out about learning as an adult, which were only relevant tangentially, and kept digressing. That 1,000-word central essay started out at double the length. I might do a grab bag of other things I’ve discovered about adult learning at some point, but I’m glad I did a second draft to bring some focus to this.

Hope this is useful to people, because it’s been very useful to me.