I promised a post about fluoridation. This is it. This may be the first of several; I won’t pretend to be familiar with any of the literature on this, whether on the health effects (detrimental or beneficial) of water fluoridation or on how fluoridation fears are an entry-level conspiracy theory. (Although, I have some anecdotal evidence — long ago I lived in Austin, TX and thought the Alex Jones/Infowars people who camped out in front of city hall protesting fluoridation were kind of campy and funny. Little did I know where we were headed.)

Leana Wen and Emily Oster both wrote about fluoridation last week, Oster in her New York Times piece and Wen for Amazon house rag The Washington Post. Their points are almost identical, which should alert you to the level of effort these brown-nosers are putting into their public intellectual output.

Both mention that European countries stopped recommending fluoridation. Hmm, can we think of anything that is different between European countries and the US of A? Here’s one: nationalized health care. In the US, dental insurance is separate from health insurance, and both are private. (Fun fact, I got two wisdom teeth extracted with nothin’ but shots of Novocain because I had no dental insurance — paid out of pocket for the extraction — and my crappy health insurance didn’t cover nitrous oxide.) Dental care is a crisis in the US, and if the legislative panels convened to worry over it don’t convince you, may I point you in the direction of the huge repository of memes about teeth as “luxury bones”? In this context, where kids go to bed suckling on bottles of Mountain Dew (is RFK gonna do anything about those Big Ag corn subsidies or are we just gonna get some kind of funky MAHA remix of the soda tax?) and many can’t go to the dentist at all, might the value of something like public water fluoridation be evident?

Anyhow, this post isn’t going to focus on that. This post is going to focus on how to read a study. Both Oster and Wen cite the same study, from JAMA Pediatrics (scoffing here because people think JAMA is some kind of prestigious journal when in reality the statistical review is shit-tier and the journal publishes mostly dreck from unqualified clinical personnel under tremendous pressure to churn out research, no matter what it says, in order to move up the rungs of competitive medical training), purporting to show an association between prenatal “fluoride exposure” (this is, I will state up top, not what the study measured) and child IQ.

(A note about IQ. I don’t think IQ is really a valid outcome measure for this type of epidemiological study, because I don’t think “intelligence” is a unitary thing that can be quantitatively measured with any kind of rigor or objectivity. The idea that intelligence is a unitary thing that can be quantitatively and objectively measured is a legacy of Francis Galton and the neo-Galtonian paradigm of psychometric measurement and assessment: the idea that mental traits can be quantitatively measured and ranked in exactly the same way physical traits can be. This became a very popular idea in America for complex reasons related, mostly, to the needs and desires of school administrators. For the purposes of this post, we will bracket these concerns and grant that IQ is a serviceable outcome measure to use. But even granting this, as we will see, whether the “differences” in IQ reported in this paper are meaningful is highly in doubt.)

One of my beliefs is that if you’re going to argue from “the data,” then you need to actually look at the fucking data. It’s clear that neither Oster or Wen (or, let’s be real, their underpaid and long-suffering assistants) really read past the abstract of this paper. But we’re going to go through the whole thing, journal club style. I did a wacky post in the manner of journal club a little while ago, looking at a study that is structurally very similar to the one we’ll look at today — you can check it out here.

The paper: Green, R., Lanphear, B., Hornung, R., Flora, D., Martinez-Mier, E. A., Neufeld, R., ... & Till, C. (2019). Association between maternal fluoride exposure during pregnancy and IQ scores in offspring in Canada. JAMA pediatrics, 173(10), 940-948.

Introduction: This being JAMA, with famously short introductions, little effort is given to the introduction — just enough to establish the literature that the paper is intervening in and why it’s different enough to justify publication. The authors nod to some laboratory studies and a meta-analysis of some cross-sectional studies done in populations with higher-than-optimal exposure to fluoride through public drinking water.

Methods: This has several parts; the Methods section of a paper is always the most boring but the most informative. I’ll structure in the way the authors do.

Cohort: The parent study (MIREC) recruited some pregnant women in Canada between 2008-2011. A non-random subset of these women’s children were given neurodevelopmental (IQ) testing at ages 3-4. 27.7% of this smaller subset were excluded because they were missing data on drinking water or didn’t report drinking tap water — again, non-random.

Exposures: The way this study is talked about is that it somehow measured prenatal fluoride exposure in children. It did not do that. The authors came up with two very crude ways to try to estimate maternal fluoride intake during their pregnancies. First, they measured the concentration of fluoride in the women’s urine, one time per trimester for a total of three measurements over a roughly 40-week pregnancy. Second, they came up with a highly synthetic estimate of women’s fluoride intake by matching women to water treatment plants based on their postal codes, using the treatment plants’ reports to estimate average fluoride concentration in the water from the plant over the duration of the women’s pregnancies, and then designing and giving women an un-validated questionnaire (meaning — they just made the questionnaire up and haven’t tested how accurate it is) asking them to answer questions about their beverage consumption. They administered this questionnaire once in the first trimester and once in the third and did some math (upward corrections for black and green tea and so forth) to estimate maternal daily fluoride intake. What I want you to notice here is: the amount of fluoride that the developing fetus is exposed to is unknown. The authors have no proposed mechanism to understand how much of the fluoride that they’re estimating the women are drinking, or that the women are peeing out on the three measurement days, actually make it to the fetal compartment, nor do they have a proposed mechanism to understand what the fluoride would be doing to the developing fetus if and when it got there. It could very well be that most of the fluoride women drink gets peed out and very little makes it to the fetal compartment. It could be that the women with higher urinary concentrations of fluoride actually have fetuses that are exposed to less fluoride, if they’re metabolizing it faster or more efficiently for whatever reason.

One of the basic principles of reproductive/developmental epidemiology is the idea of a “critical window” — different fetal structures develop at different times, and an exposure during the critical window of development for a structure can have a radically different impact than the exact same exposure outside the critical window. The critical window for the developing heart, for example, is from about 3-8 weeks (fetal age, which is different than gestational age). Exposures to teratogens within this window can cause serious heart defects; exposures outside this critical window cause more minor defects or none at all. (The critical window for the development of the central nervous system is basically all of pregnancy, but especially the first 20 weeks, which is why it is recommended that anyone who might become pregnant take a prenatal vitamin containing folate, which prevents neural tube defects, prior to conception). The better of the two exposure measurements, the maternal urinary fluoride, is based on one day during the first, second, and third trimester — each of those trimesters is about 12-13 weeks long, and each woman’s urine was measured at a different time within each trimester. So we can’t even infer anything about exposure during critical windows or the especially critical first 20 weeks of neurodevelopment from this measurement.

Outcome: The outcome is a validated IQ scale (Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-III) given to the offspring of the enrolled women when they, the children, were ages 3-4. My reservations about IQ as an endpoint are bracketed. What I want you to notice here is the long lag time between the exposure measurements — while the mothers were pregnant — and the outcome measurements in the children 3-4 years later. We will return to this.

Covariates: These are the things the authors adjusted their statistical models for — statistical adjustment is supposed to smooth away systematic differences (between, say, women living in districts with fluoridated water vs. without), leaving just differences in the exposures (measures of fluoride intake). Meh. The covariates they chose are pretty standard but by no means comprehensive. The big one they are missing here is information about how much fluoride the children themselves were consuming/were exposed to in the 3-4 intervening years between prenatal measurement and IQ assessment. Again, we’ll return to this.

Statistical analysis: The authors used linear regression, no surprise there. They used a procedure for including covariates in their linear regression models that is completely inappropriate — including only covariates that had a p-value of 0.2 or less (why 0.2? lol who cares!) in (presumably?) the full model with all proposed covariates or that “changed the regression coefficient of the variable associated factor by more than 10% in any of the IQ models,” whatever the fuck that means — but sadly common. The alternative strategy that should be used is too much to get into here but basically, it’s kind of a type of fishing to let your sample data inform what you adjust your models for; adjustment strategy should be based on a conceptual model of the causal relationship under study but, again, the authors have no plausible conceptual model to work from here.

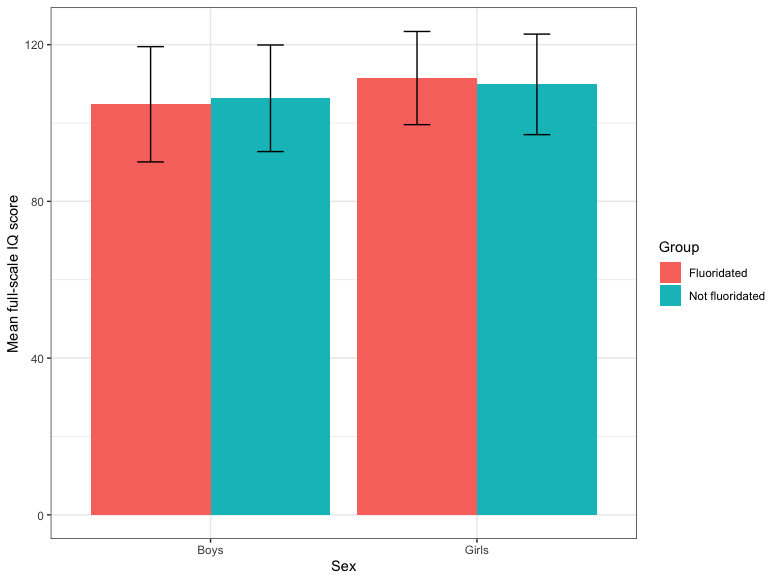

Results: Haha, oh boy. I think the authors fucked up by including descriptive results about their sample of children in Table 1. Here’s what it shows — the mean full-scale IQ (FSIQ) with standard deviation in parentheses overall and for girls and boys — both overall in the full sample and split out by whether the mothers lived in municipalities with fluoridated or non-fluoridated water. Now, what they are actually trying to measure is maternal intake of fluoride during pregnancy, but it is an auxiliary point running throughout the paper that women living in areas with fluoridated water are exposed to more fluoride (makes sense). Because looking at tables sucks (and because it’s easier to see things graphically), I took the numbers from this portion of the table and quickly generated a barplot in R. (I’ll copy/paste my code at the bottom in case anybody wants to reproduce — haven’t logged in to GitHub in forever and don’t want to deal with trying to find my password.) A barplot is not the best way to visualize these data but I just want to ask you a question here:

DOES THIS LOOK LIKE A MEANINGFUL DIFFERENCE TO YOU?

Here’s something even funnier: if we don’t break out by boys and girls, what are the mean IQ scores with standard deviation among the children born to mothers living in fluoridated vs. not fluoridated municipalities at the time of pregnancy? 108.21 (13.72) and 108.07 (13.31), respectively. These are, for all intents and purposes, the same score. There is no actual difference in IQ measured at 3-4 years for the children born to mothers recruited into this study who live in fluoridated vs. not fluoridated municipalities during their pregnancies.

So, whither the difference in boys that Wen notes? These are the linear regression results reflecting how they are modeled with respect to the exposure variables, maternal urinary fluoride and estimated fluoride intake from the questionnaire. Because of a “significant” interaction term for maternal urinary fluoride and child sex when modeling child IQ as the outcome, the authors report these separately. The results are as follows:

In boys: β = -4.49 (-8.38, -0.60), p-value = 0.02

In girls: β = 2.43 (-2.51, 7.36), p-value = 0.33

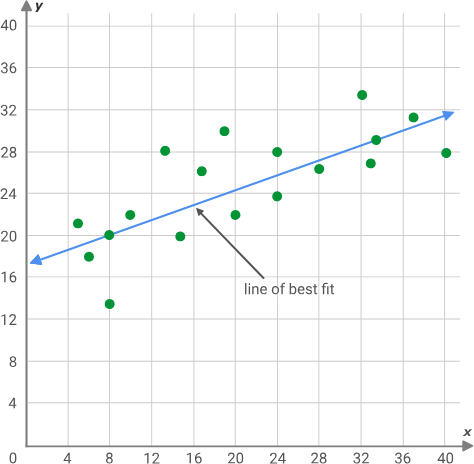

The beta coefficient above is the slope of the regression line — it is the slope of the line drawn through the data that minimizes the sum of squared errors from the line (the distance from each green point to the blue line, as shown in the generic illustration below):

I showed the “adjusted” coefficients, which means that each linear regression model to generate those beta coefficients was adjusted for the range of “covariates” I briefly noted above. The interpretation would be that for each mg/L increase in maternal urinary fluoride, the authors observed a 4.49-point decrease in full-scale IQ for boys and a 2.43-point increase in full-scale IQ for girls, holding the covariates they adjusted for constant. The p-value for the boys’ estimate that is less than the convention of 0.05 is taken to mean that that result is “statistically significant” and incorrectly interpreted as evidence that a real effect has been detected. My issues with p-values and their misuse and misinterpretation in the biomedical literature are voluminous and would take a lot more space than I currently have to get into. For now, I will just note that p-values are flukey, they depend on a lot of parameters of the data that have nothing to do with the relationship under investigation. As envisioned by their creator, RA Fisher, they’re supposed to be used in a qualitative way within a comparative experimental design where the experimenter has control over the administration of treatment or exposure, which is definitely not the case here. (As kind of nerdy little aside, one of the primary strengths of the frequentist school of statistical inference is the great attention paid to data quality and experimental design, and the great irony of the dominance of frequentist statistics in biomedical literature is that the inference techniques are applied mechanically to low-quality data, as they have been here.)

For their un-validated questionnaire measure of fluoride intake, there is no “significant” interaction detected, so the results are reported for boys and girls combined:

β = -3.66 (-7.16, -0.15), p = 0.04

So the interpretation here would be that for each unit increase of self-reported maternal fluoride intake (I don’t remember the unit, and this is a made-up exposure so I don’t really care) they observed a 3.66-unit decrease in full-scale IQ among both boys and girls, again with a “significant” p-value of less than 0.05.

I am completely not convinced that a real relationship has been uncovered here, for reasons I will get into more in the Discussion section. For now, I will just ask: whether or not it is “statistically significant” (a term that essentially… means nothing), are fluctuations of IQ score on the order of 2-5 points meaningful? Given that IQ is a fairly slippery construct (and not, like, units of mercury as in blood pressure or something like that), I’d say… no. I would especially say no in the context of the significant limitations and weaknesses of this study, the tiny effects it is claiming to detect over years with a pretty small sample, and the fact that there’s actually no difference in IQ scores among boys/girls or children in general born to moms living in municipalities with fluoridated or non-fluoridated water. I would say that the “findings” here, if we generously call them that, are actually artifacts of the research process.

Discussion: The discussion is a master class in a certain type of high-falutin’ overstatement of the soundness and the impact of the “findings.” I will skip over most of this, even though it makes me mad, because it doesn’t really matter. I want to get straight to the heart of the discussion, the authors’ own evaluation of the “strengths and limitations” of the study — I am of the school that reporting strengths is bogus (shouldn’t your study be primarily strengths?) and that the discussion is the place to discuss the limitations that should contextualize how your results should be interpreted. Let’s see what the authors themselves say.

First, urinary fluoride has a short half-life (approximately 5 hours) and depends on behaviors that were not controlled in our study, such as consumption of fluoride-free bottled water or swallowing toothpaste prior to urine sampling. We minimized this limitation by using 3 serial urine samples and tested for time of urine sample collection and time since last void, but these variables did not alter our results.

Translation: we don’t have good measurements of fluoride consumption, and how much fluoride ends up in maternal urine depends on a bunch of stuff we couldn’t measure, but we did three measurements and the stuff we could measure didn’t change anything.

Second, although higher maternal ingestion of fluoride corresponds to higher fetal plasma fluoride levels,(45) even serial maternal urinary spot samples may not precisely represent fetal exposure throughout pregnancy.

This is the stuff I was talking about earlier. They have no idea how much fluoride the children in the study were actually exposed to in utero. The “serial maternal urinary spot samples” they refer to are three single measurements taken 12 or so weeks apart across a given pregnancy.

Third, while our analyses controlled for a comprehensive set of covariates, we did not have maternal IQ data. However, there is no evidence suggesting that fluoride exposure differs as a function of maternal IQ… despite our comprehensive array of covariates included, this observational study design could not address the possibility of other unmeasured residual confounding.

Residual confounding refers to confounding that may be left over after you’ve statistically adjusted for stuff you’ve measured. The authors adjusted for nine or ten covariates that probably do matter, but there is almost certainly (not almost, there is certainly — keep reading) intractable residual confounding that makes it impossible to interpret the associations reported in this study as causal relationships between fluoride exposure and child IQ.

Similarly, our fluoride intake estimate only considered fluoride from beverages; it did not include fluoride from other sources such as dental products or food. Furthermore, fluoride intake data were limited by self-report of mothers’ recall of beverage consumption per day, which was sampled at 2 points of pregnancy, and we lacked information regarding specific tea brand.(17,18) In addition, our methods of estimating maternal fluoride intake have not been validated.

This is about the self-reported maternal fluoride intake questionnaire. Here, the authors acknowledge that this is limited, biased by being self-reported and depending on mothers’ ability to accurately recall their beverage intake per day, that this was only administered at two points in pregnancy (might someone’s beverage drinking habits change from the first to the second to the third trimester?), and that the questionnaire they used has not been validated to evaluate how accurate it is at capturing what they want it to capture. They claim its correspondence with the maternal urinary fluoride measurements give it face validity… so you say!

Fifth, this study did not include assessment of postnatal fluoride exposure or consumption.

This is the biggest thing here, and this is the only sentence that the authors dedicate to this massive, problematic issue in the Discussion section. What the authors did was correlate some very bad, inaccurate measurements of maternal fluoride excretion and intake with children’s IQ three or four years later. Some of the residual confounding they mention above is right here. What happens to those children in the three or four years between being in utero and being given neurodevelopmental testing? A lot — they could move, their fortunes or home environments could change, they might be exposed to different levels of things that enhance or hinder performance on IQ tests (enrichment activities, preschool, etc.) but one thing that might really matter for the purposes of a study aiming to investigate the effects of fluoride is: those children might be exposed to fluoride in those intervening years. In fact, all of them certainly were. This information is missing from the study.

Okay, I have written a lot just to say that this study is decidedly not evidence that fluoride at the levels of public water fluoridation might be risky for pregnant women or neurotoxic to the developing fetus. This is a crappy environmental epidemiology study built from sloppy constructs, assumptions, and data that amounts to little more than sequential convenience samples. I may dig in to some of the other papers mentioned by Oster and Wen in their articles (maybe not to this level of detail) and I’ll be surprised if I find anything much different.

It bears repeating over and over and over that Oster and Wen are trying to do, same as with Covid-19, is rhetoric. They’re trying to dom you, with data and hard-to-interpret research findings, into accepting things that are obviously bullshit — again, laundering fringe nonsense to try to boost their public profile on a cresting wave of fascist Romantic notions about science, health, bodily integrity, our precious bodily fluids and those of our children. I will give Oster some reluctant credit and say that when discussing this particular paper, she notes some “questions about the validity of the findings as a whole.” But this is nested in a cute little point about how people will do their own research (I listened to about five minutes of a podcast she did based on the NYT article and her Stassi-ass crispy R’s drove me so nuts I had to turn it off) and that public health people ought to be a lot more “nuanced” about the stuff they turn up when they do that. (“But with more detail on what the bulk of the research shows, people can understand that most studies do not support the notion that fluoride is unsafe.” I did the work for you here. You’re welcome.)

Well, now when people do their own research, they’ll turn up these two articles by credentialed experts claiming that the literature on fluoridation and neurodevelopment is a lot more nuanced than it actually is. What the fuck? Most of my smoke here is actually for Leana Wen, who to her discredit, is really fucking bad at reading studies, definitely way worse than Emily Oster. Here’s what Wen says in her article, direct quotations:

In addition, emerging research raises concerns for fluoride’s negative impacts on developing brains.

To John’s question, the studies demonstrating fluoride’s impacts are well-conducted, peer-reviewed and published in prestigious journals such as JAMA.

No they fucking aren’t. Shut the fuck up. And once again, you’re welcome for doing your fucking job for you for free. You are most certainly welcome to wire me $1500 any time you want.

R code:

df_kids <- data.frame(mean = c(104.78, 106.31, 111.47, 109.86), sd = c(14.71, 13.60, 11.89, 12.83), Sex = c("Boys", "Boys", "Girls", "Girls"), Group = c("Fluoridated", "Not fluoridated", "Fluoridated", "Not fluoridated"))

ggplot(df_kids, aes(x = Sex, y = mean, fill = Group)) +

geom_bar(position = position_dodge(), stat = "identity") +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=mean-sd, ymax=mean+sd), width = 0.2, position = position_dodge(0.9))+

theme_bw()+

ylab("Mean full-scale IQ score")

You just read issue #46 of Closed Form. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.