Tinside Lido, Plymouth (1935)

This deep dive is into a Lido! In 1928, Plymouth's chief engineer set out to create a new, healthier city, and his masterpiece at Tinside is still visible beneath the post-war plans.

Hoe means ‘high place’ and Plymouth’s is a forceful cliff overlooking the huge sweep of the Sound. Approaching it from the landward side, the Hoe rises steadily up. From the seaward side, though, the foreshore beneath the Hoe’s cliff face is needle sharp limestone rocks and treacherous black seaweed.

The Hoe is Plymouth’s equivalent of Trafalgar Square, in that it has a weight to it. Not just the rock beneath it but the history upon it. From long-lost giants and Drake’s mindgames, to 17th century fortresses and WW2 tea dances. Generations of my family are in photos taken on the Hoe with Smeaton’s tower behind us. If the Hoe is the lodestone of the city, where the weight of its past anchors it, the foreshore beneath is its pleasure ground.

In the 1930s, the city engineer had a vision for the foreshore that culminated in what is now called Tinside Lido (1935). This deep dive looks at how Tinside came about, was nearly lost and is now thriving. It’s a look not at Abercrombie’s Plymouth, but at Wibberley’s.

Plymouth’s foreshore generally refers to the shoreline of the Hoe, from where it rises by Millbay to where it curves around the fortress of the Royal Citadel to the old Barbican. Within this area there are two coves.1 The western cove includes Pebble Side and Reform Beach whilst the eastern cove is Tinside Beach. Between them is a rocky promontory. Over the last century, this whole foreshore has gently drifted towards being known as Tinside.

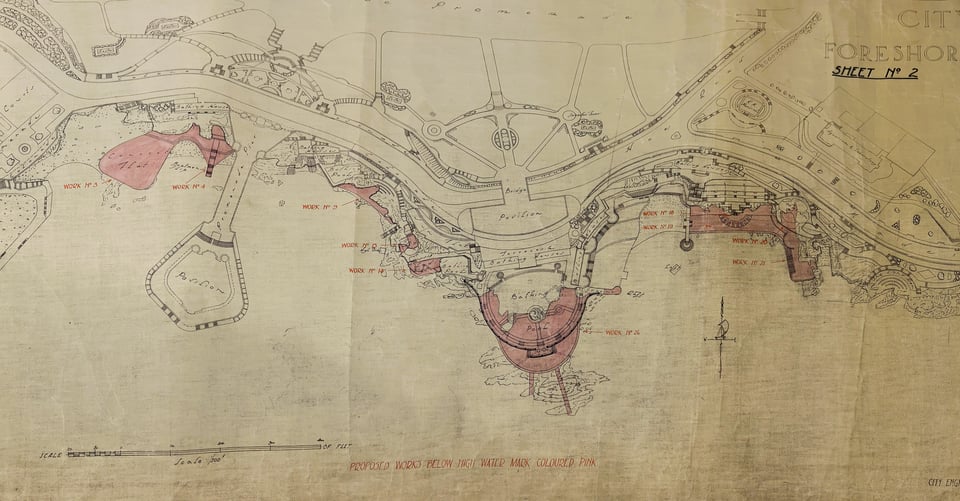

I’ll be focusing on the area developed by Captain John Wibberley in the 1920s and 1930s of which the culmination is the sea-water bathing pool and its Deco entrance building. This is now commonly called Tinside Lido. However 1930s press coverage calls all the foreshore pleasure grounds the “Lido”. It is very easy to get turned about by these changing terms, so here is Wibberley’s own development plan from 1934 for orientation.

Sea-bathing and sun-bathing

In the 1800s the natural tidal pools at the base of the Hoe’s cliff were artificially enlarged. By the 1850s, up to 1,000 people would swim off the foreshore’s tiny beaches regularly: equally split between men and women. Structures were built to offer changing rooms and, of course, refreshments.

“We know that the bathers at Tinside used to change in a tin shed and we can only surmise that that is where the name Tinside comes from.” (Robinson, 1998)

By 1913 the council had built a bathing pool near the pier, and bathing houses into the cliffs around Tinside cove.

John Wibberley

John Wibberley (c1879 to 1936) was born in Ashbourne in Derbyshire. He served his articles at Lewes before returning to Ashbourne as an assistant surveyor with the Urban Council. After a stint at Guildford he joined Plymouth, then a county borough council, in 1904. It seems likely, given his experience with water works, that he was involved in the Edwardian foreshore work.

By autumn 1914, he had obtained a commission in the Royal Engineers. After various military works around Devon, he became part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. He built roads at Kantara, defenses at Mount Carmel and a new water supply scheme for Jerusalem.

Wibberley was made deputy Chief Engineer of Plymouth in 1919 after his return from the war and was promoted to Borough Engineer and Surveyor in June 1923. He was a member of the Institute of Civil Engineers and the Institute of Municipal County Engineers. It’s clear that Wibberley was a practical man, experienced in making concrete and water bend to his design.(WMN, 16 Jun 1923)

Between 1923 and his death of heart failure in early 1936, Wibberley reshaped Plymouth. The Western Morning News, in his obituary, said:

“He had been responsible for the construction of thousands of houses, many important road and street widenings, the construction of the Embankment Road, the laying out of Central Park…and also the important developments along the foreshore which have so enhanced Plymouth’s position as a holiday resort.” (WMN, 29 Feb 1936)

By August 1936, six months after his death, the city was installing air raid precautions.

Tinside development and the Lido

In 1928, Plymouth was awarded city status by King George V. Its ambitious aldermen set about building created a masterplan for the foreshore. It started with additional bathing houses, which were opened in time for that summer. The overall scheme was described as containing “a concrete promenade, colonnades, bathing, houses and sea walls (forming an open-air swimming bath at half tide), concreting the rocks south of the women’s bathing place, forming concrete platform and children’s paddling pool, and improving the beach.” (WMN, 28 Jun 1930)

In the early 1930s there was a push to teach people to swim, and Tinside hosted regular classes. At this point ‘Tinside’ is the Edwardian and 1930 bathing houses, the large “ladies’ pool” on Tinside rocks (see 1925 photo) and the concrete steps over the rocks and into the sea, where two rafts were anchored in the cove.

It's clear from press coverage that councillors also saw the development as a way to bring tourists and generate income. Statements throughout the 1930s talk enthusiastically about the monies to be generated by hiring out deckchairs and “beach houses”.

By 1932 “the new cult of sun-bathing” had arrived, and Plymouth officially embraced it. This was a wider health movement across Europe that emphasised physical exercise and exposure to sunshine to combat illnesses.

“We make no dress restrictions and we are not at all prudish. People are given complete freedom within reason, and I have only heard one complaint about bather’ conduct since we introduced sun-bathing.” (WMN, 23 Jul 1932)

“Not at all prudish” feels like an understatement, since the Lion’s Den - a men only bathing place on the eastern side of the cove - was known for nude swimming and sunbathing well into the 1970s.

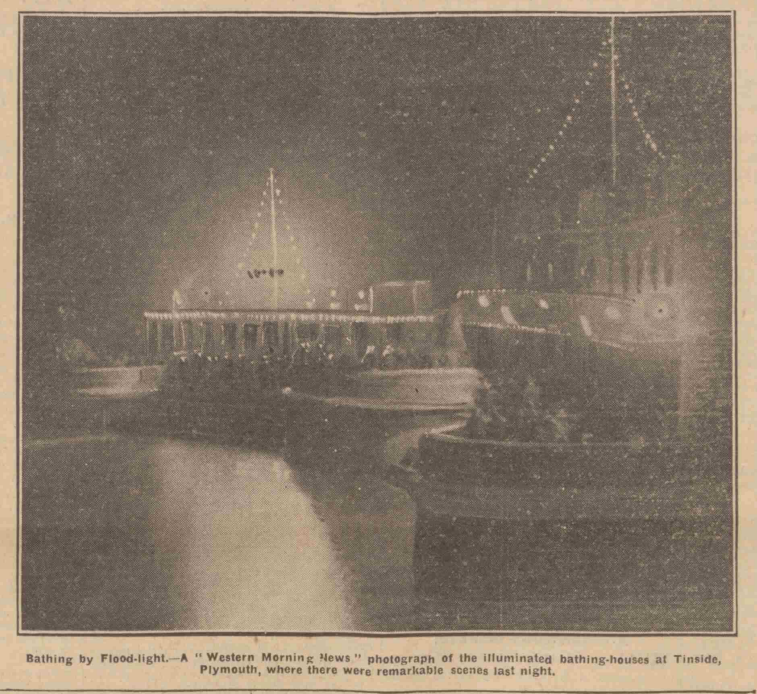

The council also installed floodlights in 1932 to allow nighttime bathing.

This proved so popular with both bathers and spectators that by the fourth night the police were called to manage the crowds. The site only had one combined entrance and exit, with a single ticket office. The crush of people around this pinch point was so great that a few women fainted once they were safely out of it. Despite the chaos, over 2,000 bathers took a swim that night. (WMN, 27 Aug 1932) Within a few days, separate entrances and exits had been set up. This 1930s photograph of Tinside gives a sense of how thousands of spectators could have watched the lightshow.

Over the next two winters, more improvements took place under Wibberley’s guidance, including a glass-roofed semi-circular sunbathing area at the Lion’s Den in 1934. Mentioning the Lion’s Den to people now tends to elicit a raised eyebrow and a knowing look. As well as a place for men to swim and bathe nude, it was also a secret cruising spot for gay men.

The Colonnade

In 1935, Wibberley’s promenade and colonnade were built. This sweeps in curves around the rocky foreshore, an exercise in concrete cantilevering. Above are the road and pavement, below a colonnade with built-in benches and uninterrupted views of the Sound.

The sea-water bathing pool

Finally, on the evening of 2 October 1935, timed to coincide with the King’s Silver Jubilee, the new “sea-water bathing pool” at Tinside opened.2 This is what we now call the Lido. Despite the cold mizzle that night, the local bathing clubs put on swimming displays under the floodlights.

This is Wibberley’s masterpiece. His design makes use of the existing rocks: in one drawing in the archive, it becomes clear the huge central fountain is where it is because there was a large rocky outcome in the middle of the planned new pool. He also had to contend with the need to keep a navigational aide at the tip of the rocky outcrop. So, he built a pool that looks like the prow of a liner. The curved pool elegantly sweeps around, with an additional low platform on its tip that once led down to a concrete step into the sea. The unmovable navigational aid becomes a feature: part of the ship-like language of the design.

His drawings also show how seawater would be drawn in, filtered and aerated by the fountains and then cycled back out. This is a sanitation engineer’s design. His 1932 report on the state of the foreshore had warned “the existing sanitary arrangements are far from satisfactory”. Looking at it solely from that angle misses the fine aesthetic design. The pool juts out, its deep end furthest from the shore so swimming ‘out’ replicates the sensation of swimming out into the sea. This deep end originally had a concrete diving board in it.

1930s Lido entrance building and changing rooms

In the late 1930s, after Wibberley’s death, the last part of his plan was built. This new two-storey entrance building and changing block sits the width of the pool and was based on his 1935 design. It has a sun terrace on top and is concrete, rather than the local limestone of the earlier blocks. It has metal-framed windows running the width of it. The staircase is housed in a tower that goes higher, reaching the roadside and roof terrace, with huge glass-block windows set between fins.

Internally, the staircase is lined with blue and red tiles, and an elegant brass banister (see photos further down). Above the outer doors, the simple cantilevered concrete porches have a decorative bas-relief pattern of triangles and quarter circles in them.

I had thought this was built in 1936, but subscriber Micky West flagged the 1937 aerial photos of Tinside. These show the older block still in place in 1937. Since there were restrictions on building materials during and after World War Two, that suggests the current entrance building opened between 1937 and 1939.

Early use

“The new swimming pool and sun terraces will attract what may be called the best type of visitors, and the rocks and unsightly beaches are being treated very artistically.” (WMN, 23 Jul 1935)

The Tinside complex was a huge attraction, with its new Deco bathing pool as its jewel. At night, the fountains would be lit up by lights that changed colour, and music played through a loudspeaker system. It must have glittered. In the winter of 1937 to 1938, the pool was repainted Nile green. Perhaps that was part of the work to build the new entrance building and changing rooms?

Tinside and the Plymouth Blitz

Plymouth is a naval city, which is why it started air raid precautions in 1936, a full three years before war was declared between Britain and Germany. Come the night of 21 March 1941, several high explosive bombs hit Tinside, as recorded in the ‘bomb book’. I’ve seen suggestions that the big pool was used as a landmark by bomber pilots. Its unnaturally regular features and glass must have caught the moonlight during the blackouts.

A 1948 aerial photo shows the main pool back in use, with its now iconic striped bottom.

Post-war pleasure grounds

Both the big pool and the foreshore became part of life in post-war Plymouth. By 1950, swimming classes had resumed, including for children from the city’s schools.

“Fond memories of that beautiful pool, except when we went for school swimming lessons in the wind and rain!!” (Facebook user)

“Loved going there. My sister and I got the worst case of sunburn ever when we fell asleep on the top deck after a swimming session.” (Facebook user)

For the generations that learnt to swim there, it became the place to hang out.

“I went there every Summer's day I could from 1961 to 1972 absolutely fantastic memories. The lifeguards were great…the best one of them all was Harry a great big rotund man with the best suntan ever and always smoking a pipe.” (Facebook user)

For anyone unable to afford the Lido’s pool, swimming at the Lion’s Den or Reform beach was free. Young people would also climb the rocks to get into the big pool at night. One local recalls “Skinny Dipping after the clubs kicked out.” (Facebook user). This wasn’t a new phenomenon. A press cutting from back in 1932 says the council had changed one of the rafts’ design due to “boisterous bathers” repeatedly capsizing it.

Rescue

As the 1980s arrived, use of Tinside Lido declined. In 1998, local historian Chris Robinson suggested this was due to the state of the water in the surrounding Sound.

“Because an afternoon swimming was not just about using the pool it was swimming out to the raft and no-one wanted to do that when there were condoms and excrement and other nasties floating around.” (Herald, 26 March 1998)

However, I’d suggest another reason was that by the late 1980s, all the foreshore focus was on the Plymouth Dome (City Architect’s Department, 1988). This was a visitor attraction across the road from Tinside. When Bridget Cherry updated the Devon Pevsner, the Dome was mentioned: Tinside was not. By 1993, Plymouth City Council had started seeking a developer or lease for Tinside.

“Although the Council would ideally wish to see the retention of Tinside pool as a swimming pool in any proposals, this is not essential and submission of other options will be welcomed.” (3642/1624)

The council did get a proposal for an “other option”. A Plymouth businessman drew up plans for a dolphinarium, where dophins would be held in captivity and trained to perform. This plan was rapidly withdrawn after protests.

The Millenium Commission had been set up in 1993, with a remit to spend National Lottery monies on large scale projects. Plymouth put a bid together, drawn up by city architects Burke Rickhards, to renovate Tinside. There would be a glass fronted building with a covered theatre and sports arena. There’d be an interpretation centre, cafes, restaurants and a new public promenade. But there would be no swimming pool. (Herald, 28 Apr 1995). The bid failed.

“Where once swimmers crowded like penguins the murky silent waters now leave a melancholy tide of scum around the empty and desolate pool side.” (Herald, 24 May 1997)

The council began to consider demolishing Tinside, apparently at the prompting of Plymouth Chamber of Commerce. Lidos had had their day, as the decreasing numbers of them left around the UK showed. A group of local residents hurriedly set up the Tinside Action Group (TAG) in response.

The group launched a petition, gathering 70,000 signatures over six months. They protested outside council meetings. And, crucially, they applied to the Heritage Minister for an emergency listing. The newly renamed C20 Society added Tinside to its “at risk” list.

“Tinside is an important building and our committee unanimously vote to support its listing. We are not in the business of saving museum pieces and we believe there could be a future for Tinside.” (Herald, 23 July 1998)

In November 1998, the Grade II listing was duly granted to the Lido (covering the pool and its entrance building). Two years later the colonnade was also given Grade II status. Wibberley’s masterpiece was secured. Sort of.

Restoration and regeneration

One of the problems with the pool was that lack of maintenance, so evident in the 2000 photos, meant the restoration was a far bigger job than if it had been kept in good condition.

Plymouth ran a competition for architects and John Allen and Avanti architects were awarded the contract for its redevelopment in 2002. (C20 bathing belles) It’s unclear when the older pools along the foreshore were filled but by the 2010s, only the large pool and the various bathing houses remained. The pool itself was stabilised and restored, though only the ground floor changing rooms of the entrance building were opened when the pool reopened on 15 August 2003. (BBC news)

In 2014, just over 15 years after the demolition was mooted, Tinside was one of the ten stamps in the Royal Mail’s ‘Seaside Architecture’ series.

Now and into the future

In 2017, the council’s strategic vision for the foreshore looked at the existing buildings, and how they needed modernizing. Since then, there’s been a steady programme of improvements of both the foreshore and the Lido itself. These have been funded by both the National Lottery and the Plymouth Sound National Marine Park.

The Park aims to keep the Sound clean and reconnect the city and its people to the sea. As part of that, it’s working with Plymouth Leisure to improve the foreshore. Its volunteer teams arrive at Tinside after the last winter storms to help scrub away the debris and bird mess so the pool is ready to reopen in May.

The latest round of grant funding from the Marine Park and National Lottery have brought the second floor of the 1935 changing building back to life – after nearly 30 years - as an event space. The newly renovated sun terrace on the roof of the entrance building has a small café where the profits go back into the youth programme.

Plymouth Leisure’s youth team have a permanent base at the Lido, where they teach young people how to swim safely in the Sound as well as in the pools. One storeroom in one of Wibberley’s first bathing houses is filled with wetsuits ready to be lent to kids.

And this summer season, nearly 150,000 tickets for swimming there were sold.

On the October day when I visited, the sun terrace was warm enough that I took my jacket off and nearly dozed off watching the activity in the Sound. As I left, I saw a swimming group using Wibberley’s old concrete platforms at Reform Beach to reach the sea’s edge.

At Wibberley’s funeral, the pastor spoke of his work, saying that “within the precincts of the city and on the foreshore were monuments of his work, his vision, his untiring zeal and energy.” (WMN, 4 Mar 1936) Not only Tinside Lido but the colonnade and even the old concrete platforms are the pieces of Wibberley’s work that have survived: a vision of a cleaner, healthier city.

Back when I started this project, I wrote of my family’s excitement to move to a council house overlooking Devonport in the 1930s. A house on whose step I sat as a child in the 1970s. On that same trip I first visited Tinside. I now know that I was discovering Wibberley’s Plymouth. Just as the foreshore sits beneath the pomp of the Hoe, Wibberley’s city lurks beneath Abercrombie’s. It’s a Plymouth that wanted, and still wants, its residents to safely enjoy the ocean that made the city.

Tinside Lido details

Tinside Lido, Hoe Road, Plymouth, PL1 3DE

Architect(s): John Wibberley of Plymouth City Council

Builders: Edmund Nuttall and Sons and John Mowlem and Company.3

Date: 1935

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Plymouth Leisure, who operate Tinside Lido, for showing me around the renovated buildings and pool. I can 100% recommend a coffee on the terrace if it’s sunny.

The Box Plymouth provided access to Wibberley’s plans and other material about the foreshore and Tinside, and permission to reproduce the map and other documents. You can browse their many scanned photos and postcards of Tinside in their catalogue.

As ever, the local history group on Facebook has provided many leads and memories. This time is was the Plymouth History group.

Sources

Harwood, Elain. Art Deco Britain (Batsford, 2019)

Cherry, Bridget and Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Buildings of England: Devon (Penguin, 1989)

Plymouth City Council, The Hoe Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan (revised 2009).

LDA Design for Plymouth City Council, Plymouth Waterfront Strategic Masterplan (2017).

Chaning, Paul and Holden, Paul. National Marine Park Heritage Statement: Tinside Lido And Foreshore Plymouth Hoe (BluePrint Architectural Workshop, 2021).

Tinside Lido and changing rooms official list entry. (Historic England, 1998).

Tinside Colonnade, promenade and sun terrace official list entry (Historic England, 2000).

1935 Souvenir programme from the opening of the new sea-water bathing pool, held at the Box, Plymouth item 3642/455.

1993 Tinside Pool (Lido) sales particulars, held at the Box, Plymouth item 3642/1624.

Plymouth’s Probable New Surveyor, Western Morning News, 16 June 1923 (£).

Great Loss to Plymouth, Western Morning News, 29 Feb 1936 (£).

Catering for Bathers, Western Morning News, 28 June 1930(£).

Miller, WA. Sun Worshippers: Plymouth’s Ample Facilities ‘Neath the Historic Hoe, Western Morning News, 23 July 1932 (£).

Mass of Night Bathers, Western Morning News, 27 August 1932 (£).

Plymouth as Seen by Visitors, Western Morning News, 23 July 1935 (£).

Robinson, Chris. Jewel in the Sound, Evening Herald, 26 March 1998 (£).

Morgan, Emmanuelle. Bathing belles in peril: Lasting Lidos. C20 Society, 3 Sept 2001.

Morgan, Emmanuelle. Lido update. C20 Society, 3 May 2002.

Sparkle returns to art deco lido. BBC Devon, 14 Aug 2003 (via the Internet Archive).

Moore, Ed. Tinside Lido through history: Rare pictures of Plymouth's iconic landmark, Plymouth Live, 19 Aug 2018.

Pictures of beautiful lost moments at Plymouth's lidos and pools, Plymouth Live, 20 Jun 2020.

Dowick, Molly and Watson, Eve. Inside The Lion's Den: Plymouth Hoe's former meeting corner for gay men, Plymouth Live, 7 Feb 2021.

Celebrating Tinside Lido Campaign, Westward Shipping News blog. 9 June 2023.

Endnotes

In fact, an 1850s map calls the foreshore “Two Coves Bay” (see the National Library of Scotland’s online map tool). ↩

The gloriously triangular Jubilee Pool in Penzance also opened in 1935, hence the name. ↩

John Mowlem, who founded the company, was from Swanage in Dorset - as mentioned in the news round up earlier this month. ↩