The Amulet, Shepton Mallet (1975)

In 1971, Shepton Mallet's town centre was dying. One man, with a vision and a fawn, stepped in to rebuild it. And in the process created one of the most unique 1970s buildings in the country. I take a deep dive into the Babysham brutalist-inspired Amulet.

“I wanted to repay the town. When you are the major industry in a small place and you provide employment to many in the community you have a certain responsibility to that community.” (Shepton Mallet Journal, 4 Dec 1975)

Shepton Mallet is a small market town, tucked into a fold in the Mendips. It’s less than 3 miles, as the crow flies, from Worthy Farm where most years Glastonbury Festival emerges from the lingering mists around the summer solstice, like a chaotic west country Brigadoon. This is cider country.

This month, I look at a community centre, built by a wealthy industrialist to repay the people whose labour that had provided him with his fortune. The people of the town are currently trying to buy his gift to them, the Amulet in Shepton Mallet, back. It’s a story that connects to the rise and fall of regional theatre, and the rise and fall of a single drink.

In the 1650s, Gabriel Showering started a small brewery in Shepton Mallet in Somerset. By the 1940s, the Showerings owned a couple of pubs and a fleet of rather knackered delivery vans. Francis Showering, born in 1912, had gone to the local Grammar, and then as far as Bristol where he trained as a chemist. He came back to the family firm where they were still brewing beer and cider. He decided to try to create a sparkling perry – a cider made from pears. He tested it at various agricultural shows in the area before launching it in 1953. As Babycham.

It was a huge hit. The family’s factory at the edge of Shepton Mallet switched their production over to the drink. At its peak, they were producing 144,000 bottles an hour. The cute fawn brand started buying up other names in the drinks industry, such as Brit-Vic and Harvey’s Bristol Cream. In 1968 the Showerings sold the company to Allied Breweries for £108 million. Francis took a seat at Allied as a director, with his nephew Frank as vice-chair.

Across town, in 1967, the Shepton Urban District Council decided they needed to widen the main road through the town. Perhaps future echoes of lost festival goers trying to find the big Tesco haunted them. They bought some old buildings up and knocked them down. Then they changed their minds about the road and instead looked for a developer who might like to take on the derelict plots. Every plan fell through.

The Shepton Mallet Journal, writing later, said:

“Back in 1971 Shepton Mallet was a town with no future. Shops were derelict, trade was stagnating, and no-one was interested in the place.” (Shepton Mallet Journal, 4 Dec 1975)

In 1971 Francis Showering had had enough. He offered to buy the land and finance the redevelopment himself, with some of the millions he’d made in the factory.

Design and construction

Before talking about the architect and the theatre, it’s worth a digression into the cultural context.

The mid-century regional theatre boom

In the 1950s and 1960s, repertory theatre – local theatre companies that put on works from a specified repertoire - had acquired a negative reputation. Like cinema, it was also battling with the arrival of mass market television. Hazel Vincent Wallace, an actor-manager and member of the Council of Repertory Theatre, pushed for rep to be rephrased as regional theatres.

“ ’Regional’ not only stressed the local loyalties of public and programme…but emphasised the semi-permanency of those theatres which retained a resident company.” (Rowell and Jackson, 1984)

Despite the allure of TV, the postwar years saw a boom in regional theatre construction. Dr Alistair Fair, Reader in Architectural History at Edinburgh College or Art, highlights that most of these were funded through The Arts Council of Great Britain and their 1960s ‘Housing the Arts’ scheme. What makes the Amulet unusual, he points out, that it was a privately funded theatre. (Amulet Heritage Statement, 2025).

Wallace had built her theatre in Leatherhead, the Thorndyke (1969), as a community space. It was to be open as a coffee lounge by day, and a theatre by night. She funded it through public subscription, with the people of the town donating towards it. In contrast, Showering was a paternal figure who decided to purchase the land and redevelop it. He was also clearly someone astute enough to trust his team.

The design of the town centre

“I wanted shops, a supermarket, flats and a hall. So I called the architects in and did not set a price limit. I told them to tell me how much it would cost then we would see if that was within my budget.” Francis Showering (Shepton Mallet Journal, 4 Dec 1975)

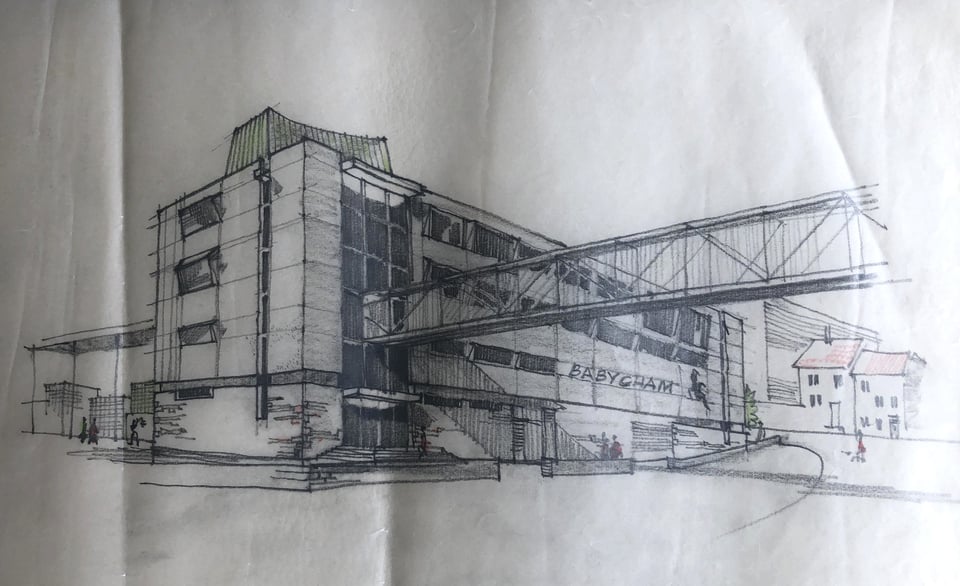

The architects he chose was Wyvern Design Group who had offices in the west country. The group had already delivered a new office building on the Showerings’ factory site on the edge of town in 1968.

That had hints of the brutalist movement with its concrete hoods around its windows.

The lead architect on the offices, Terry Hopegood RWA, was appointed lead for the town centre redevelopment. Hopegood had studied at the Royal West of England Academy, Bristol School of Architecture (now part of the University of Bristol).

As well as the offices for the Showerings, Hopegood was also doing a fair bit of work for Barclays’ Bank. That will become relevant.

Hopegood’s own notes on the job (Hopegood Archive) say the client’s brief was as follows:

Use Somerset County Council’s “Guide to Developers”

Use natural materials wherever possible

Produce the kind of development considered right for Shepton Mallet.

The first of these requirements was a plan drawn up by the local authorities that indicated the scope and type of development they were expecting in the town. This guide had been produced to encourage developers to take on the contract but had been the cause of every one of them failing to find a way to make the scheme turn a profit. Showering, unlike the property developers, wasn’t looking at the bottom line.

“I was fortunate enough to be in the position to do the redeveloping. I am sure anyone else in my position would have done the same. I will get some return from the money but not a sensible commercial return. I never expected it. It was not a viable proposition.” Francis Showering (Shepton Mallet Journal, 4 Dec 1975)

Showering wanted the whole redevelopment to create an active town centre. Shops and a supermarket would bring people to it by day, and the hall would provide entertainment in the evenings. And there were 26 sheltered flats above the shops, providing accommodation for the elderly. The close proximity of the shops and the hall would allow the residents more independence by placing everything they needed within walking distance.

“I invited the people of the town to say what they needed and, as a result, a number of additions have been made as the scheme progressed.” (Showering, Western Daily Press, 5 Dec 1975)

Hopegood, along with job architects Paul White and Henry Alpass, created a contextual scheme that worked with the site and the remaining buildings. Showering sent Hopegood to Bruges in Belgium, no expense spared, to get some clear thinking time.(Shepton Mallet Journal, 4 Dec 1975, notes from Let’s Buy The Amulet interview with Hopegood.)

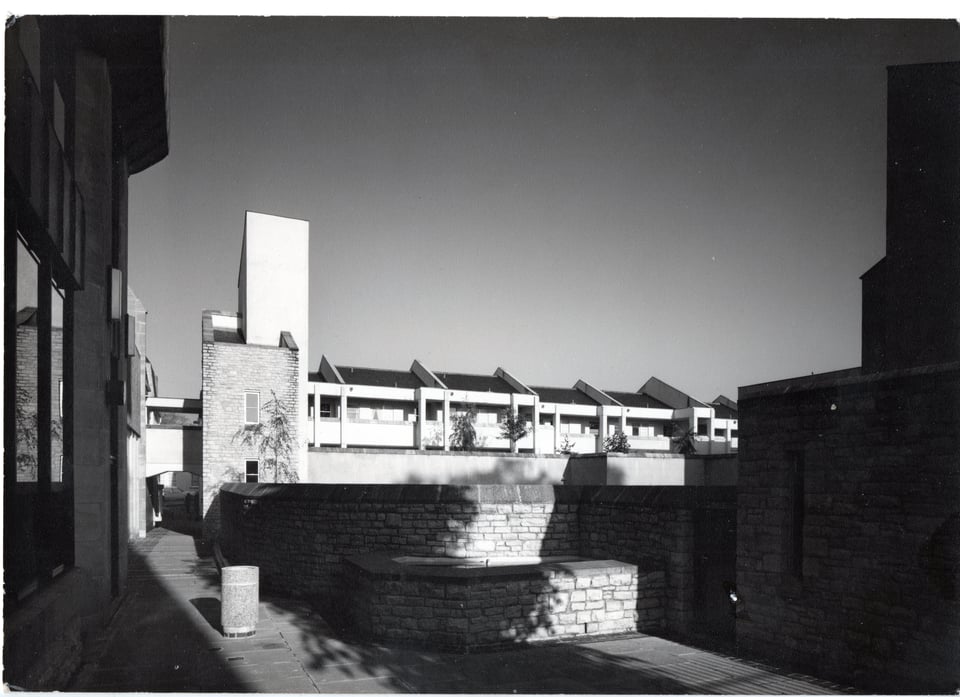

Extant buildings were repaired and restored. The new shops and flats – of which Showering was clearly proud – are straightforward. To the rear, overlooking the churchyard, the flats have a classic street in the sky. It was wide enough, apparently, for the residents to sit out in the sun in summer. At the front the flats had bay windows so the residents could enjoy watching the comings and goings on the newly pedestrianised street.

It was with the loose ‘hall’ brief that the team went bold. Almost brutally bold.

The Centre (now the Amulet)

The hall part of the design was to be a flexible community space, just as Wallace had built in Leatherhead. It included a bar and lounge area, called The Black Swan, as well as the theatre space. Alistair Fair highlights that this postwar drive for community centres was built on earlier traditions such as the village hall. But whereas Jellicoe, designing Totnes’s new Civic Hall in 1962, went for the strict linearity and grid system of the European modernists, Hopegood drew on British brutalism for his hall’s form.

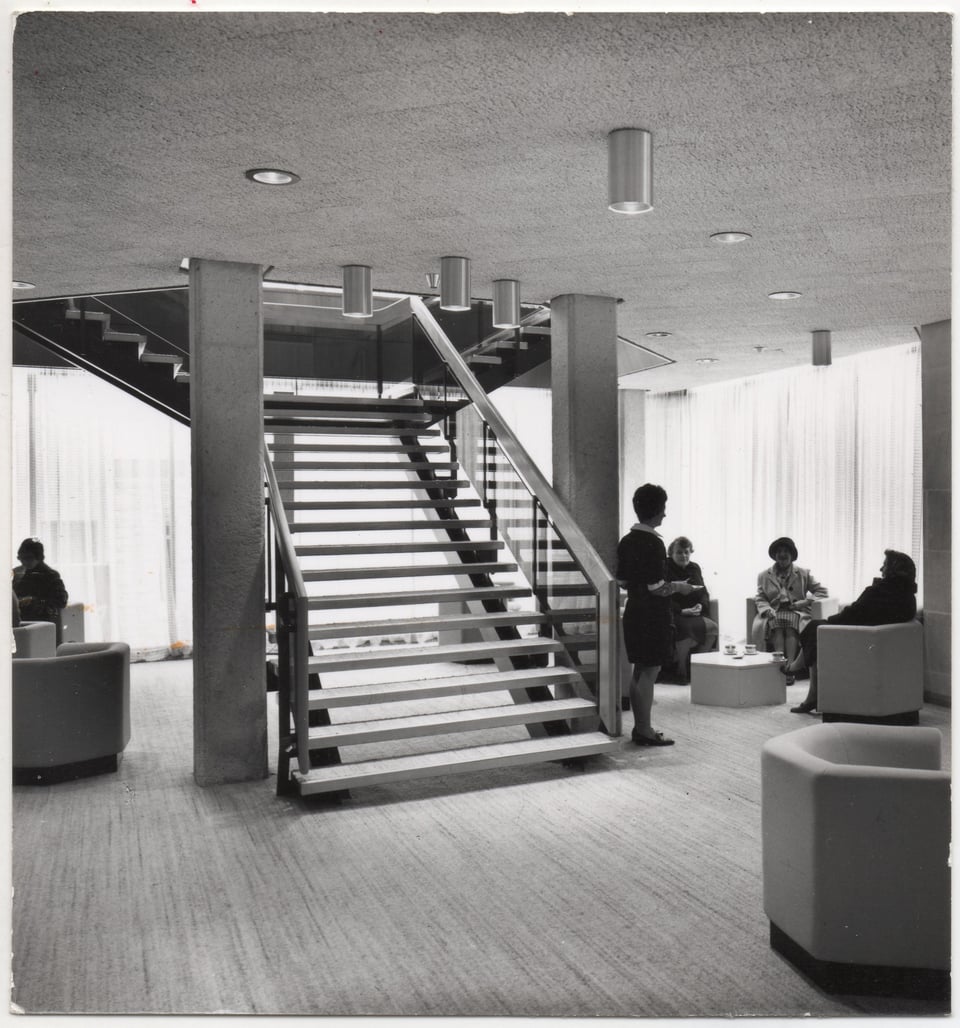

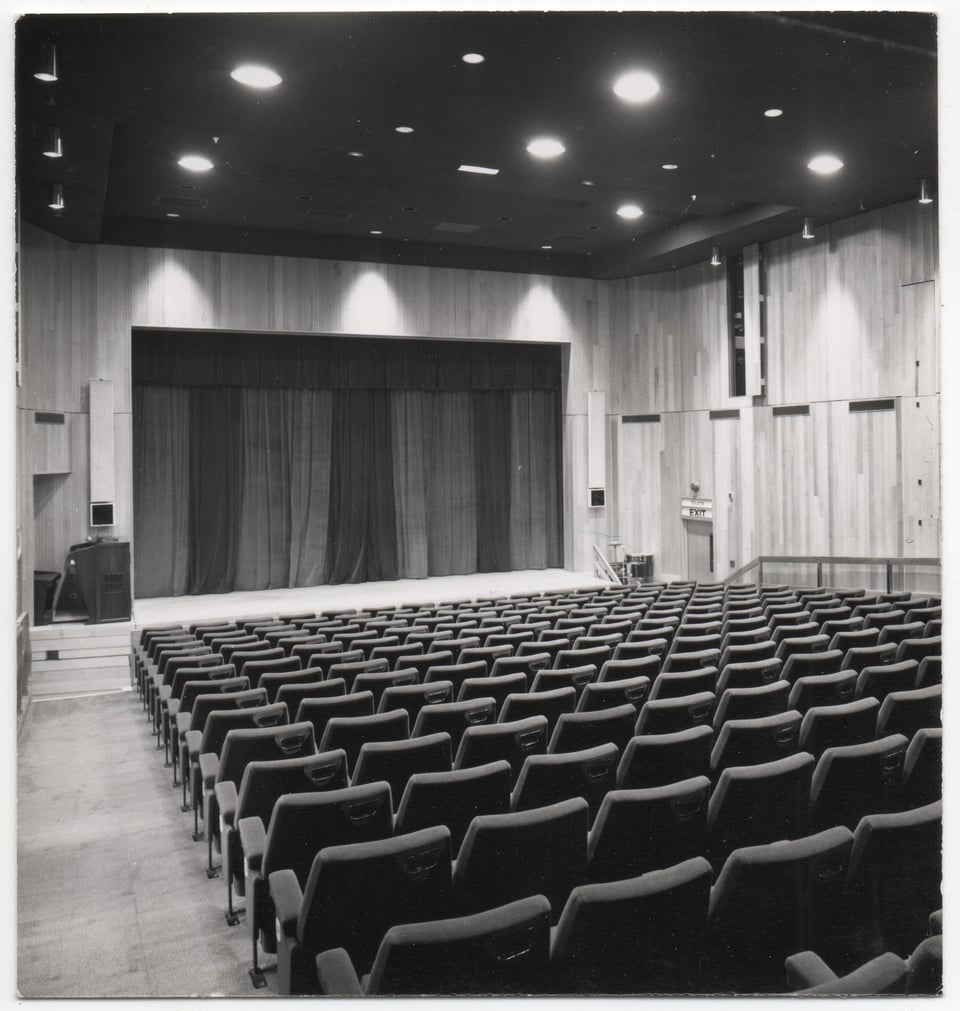

The building uses overlapping polygons of different sizes to create a series of functional spaces. Interior photos from 1975 show that building elements like the stair well followed the theme. Even the seating and tables in the bar and foyer were octagonal.

An early leaflet advertising the Centre, as it was then called, repeats this theme in the logo.

Another leaflet explains it. The Centre’s main entrance sits by the 1841 Market Cross, which replaced earlier versions. The cross is an octagonal open arcade with a spirelet springing from a central bench pier. The polygons of the Centre are part of the contextual design of the whole redevelopment rather than a digression from it. They echo the six sides of the market cross it sits beside.

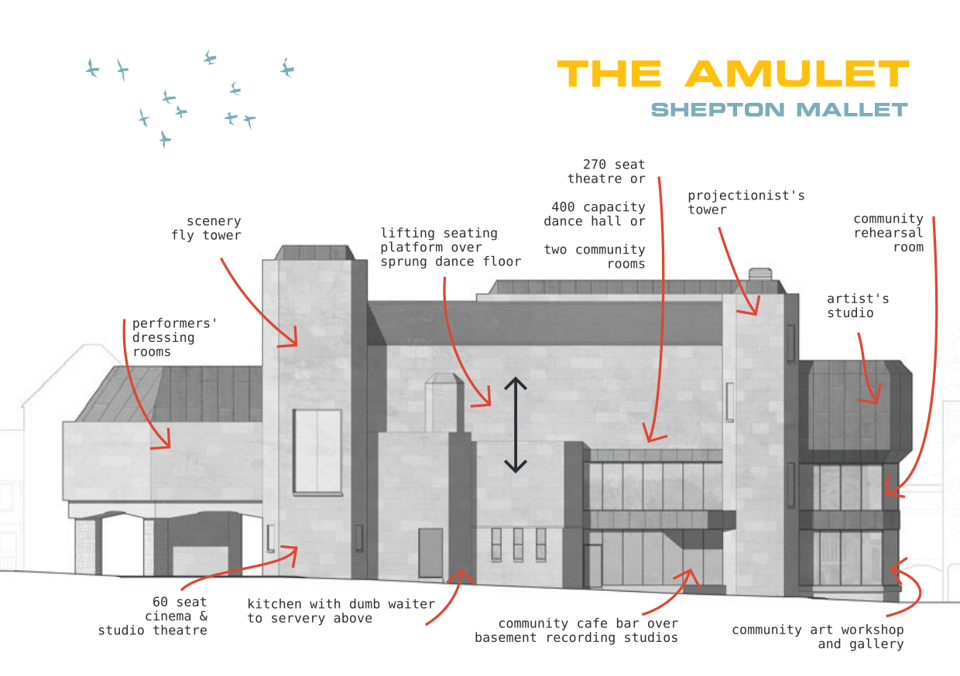

Externally, the various polygonal blocks were clad in different materials. The committee room was originally clad in vertical seamed lead, balanced above the glass curtain walls of the offices and kitchens. The fly tower, which also has a town clock on the outside, was clad in local ashlar stone from Doulting. That matches the stone of the nearby church, showing the sympathetic way the team approached the whole site.

The most radical part of the theatre, and the part that makes it probably unique in the country, is how Hopegood approached the need to serve multiple purposes. The entire ranked seating – all 200+ seats – is bolted to a platform that can be raised into the ceiling.

With the seating retracted, the hall could then be used for discos, exercise classes, fetes and the like. With the seating down, it worked as a theatre or cinema.

“I was employed by Barnes and son. And I helped to install the mechanism to raise the seating to use the dance floor beneath it was quite a piece of engineering and worked well.” (Steve, Let’s Buy the Amulet)

Hopegood had heard about this idea from a senior director at Barclays Bank who mentioned they had something like it at their London HQ.

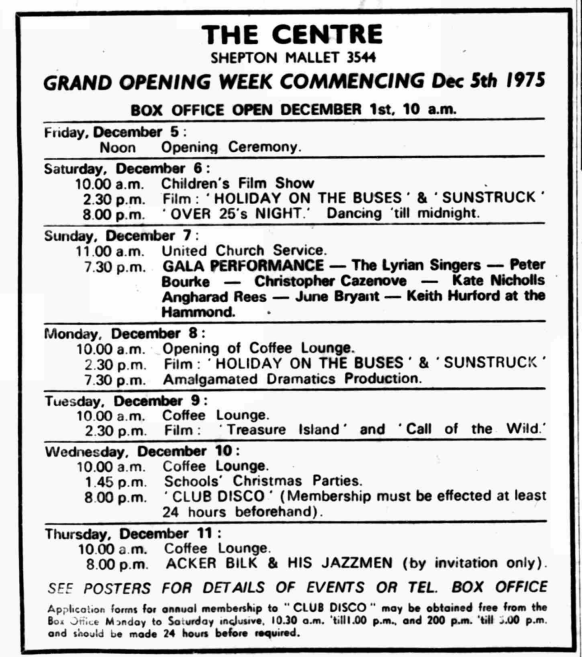

Work started on the site in 1973. Showering officially cut the ribbon on 5 December 1975. He said: “This is the day for which have been waiting since that public meeting in 1972 when the people of Shepton Mallet gave me the green light to go ahead with the redevelopment of our town centre.” (Bristol Evening Post, 6 Dec 1975)

The moment was captured on a silent newsreel which is now on the BFI player.

Early use

The mixed use of the venue is apparent from the opening week’s programme. A Saturday morning film show for kids (films unknown), Holiday on the Buses (1973) and Sunstruck (1972) screenings, an Over25’s night with dancing till midnight. A church service, a gala with Christopher Cazenove and Angharad Rees, a drama, school Christmas parties and a club disco. Oh, and Acker Bilk and his Jazzmen.

A year later, in December 1976, they’re advertising that the coffee lounge is open every day from 10am, the restaurant is serving lunches from noon to 2.30pm, and full a la carte from 7pm until midnight.

“I worked in the Black Swan Suite waiting tables at lunch, I remember the Rotary club lunches, and I heard Bohemian Rapsody for the first time while laying up, never heard anything like it before. Also Pantomimes that my grandchildren performed in, was a brilliant venue. The seats going into the ceiling was a first, we were so impressed with that.” (Yasmyne, Let’s Buy the Amulet)

As well as dancing, food and cinema, there was a folk club on Wednesdays. And Francis Showering still took his role as the town’s benefactor seriously.

“We held our wedding reception in the Black Swan in 1980 when my mum was bar manageress and Francis Showering provided the official toast on every table.” (Mike, Let’s Buy the Amulet)

The Centre was renamed the Amulet in 1990, after the discovery of a Roman Chi-Rho amulet in the town. (It turned out to be fake.)

“Loved the Pantomimes also used to go in on a Friday morning with friends for a cup of tea after school run.” (Margaret, Let’s Buy the Amulet)

Decline

Francis Showering had no children. His nephew Frank had joined him at Allied Breweries, rising to become Chief Executive. When Frank unexpectedly died young, Francis decided to rebuild a family-run business. He started a new perry company with his great-nephews, Frank’s four sons, in 1992. The Brothers brewery started by taking their new pear cider around the local shows and festivals. Including 3 miles down the road to Glastonbury Festival. Just as their uncle had found forty years earlier, their product was a huge hit. The Showering Brothers would go on to buy back their family’s factory in 2016, and then to buy back the Babycham brand in 2021.

But back in 1995, Francis Showering died. His benevolent ownership of the Amulet was over.

By 2006, Kevin Newton owned the building and in 2007 Bristol Academy of Performing Arts took occupation, renaming it the Academy. Since then, the building has gone through multiple changes that have reduced the original design and have steadily removed it from its original intent. The Academy rebuilt the units next to the theatre, replacing the boxy projecting windows with a neo-Georgian façade and punching windows into the eastern elevations.

By late 2010 most of the lead cladding and roofing had gone, replaced with render or tiling. And then the building had a catastrophic roof leak. The water ruined the ground floor ceilings, the original theatre seating and the dance floor beneath. The Bristol Academy of Performing Arts went into administration within a year, and the Amulet was closed. It has remained dark until this summer.

In 2012, the theatre was effectively cut in half. The public stair from the ground floor to the theatre space was removed and closed off, leaving a blank octagonal block of concrete in its place. Rumours suggested Wetherspoons was planning to turn the ground floor into a pub. This wasn’t true. Whoever was planning to open a pub stopped before all the works they had started were complete.

Future

“As a teenager / young adult our friendship group regularly used the amulet, unable to drive, it was a fantastic resource on our doorstep. It was hugely popular, and I think it could be again.“ (user, Let’s Buy the Amulet)

In 2015 the owners were given permission, on appeal, to convert the committee room into a standalone flat. In 2020, a gym opened in part of the building and the buildings’ owners sought permission to convert the theatre into seven 1-bed open market flats and a shop. This application is still on-going.

In 2022, the Amulet was added to the Theatre Trust’s ‘at risk’ register. They highlight their concerns about the proposal:

“The full proposals would see irreversible alteration that would result in the permanent loss of this theatre as an asset for the town and its people. It would also see a private individual profiting from what was a gift to the people of Shepton Mallet.” (my emphasis)

The Shepton Mallet Neighbourhood Plan supports the creation of more 1-bed homes but states the main demand for them is for social or affordable homes, not open market ones. And the plan is also clear that the town centre needs reinvigorating, just as it did in 1971.

“Comments from earlier consultations highlighted the lack of a focal point or venue in the town where productions, events, music can be held, and people can congregate – this was previously achieved through the Amulet Theatre before its closure in 2012. However, there are plans to regain ownership of the Amulet and develop a vibrant event centre linked to a thriving evening and social economy” (Shepton Mallet Neighbourhood Plan, 2025, page 55)

The plan also states that, as a matter of policy, the Amulet should be retained and modernised to meet the community’s needs.

“The loss of these facilities, or any significant reduction which would impact on their viability, will be strongly resisted.”

In 2023, a community benefit society, Let’s Buy the Amulet was set up. Their aim is to the Amulet back from its current owners and re-establish it as the community hub it was designed to be. The group have received grant funding from the Architectural Heritage Fund, the Community Shares Booster Fund and the Theatre Trust’s Resilient Theatres: Resilient Communities fund.

This year, Cambridge Arts Theatre donated 400 seats to the Amulet, to replace the ones ruined in 2010. And the C20 Society have back the plans to buy back the theatre. Ian Chalk Architects, who have restored the Troxy Cinema in Mile End and transformed the 1970s Camden Town Hall extension office block into a hotel, have drawn up ‘meanwhile use’ plans.

In May this year, Let’s Buy the Amulet launched their community share offer with the goal of raising £200,000 towards buying the theatre. And in early July, the summer season of pop-up events will open with a gig by Mark Chadwick of the Levellers, followed the next day by Shepton Mallet Big Band. They’ve built a temporary 60 seat cinema on the ground floor, and a box office.

These activities enable the group to demonstrate the building’s potential as a creative and social hub for the town. Perhaps the most impressive thing here is that the current owner is working with the group, so the building isn’t simply dying whilst its future is worked on.

In the early 1970s, Shepton Mallet town centre was regenerated by one man who wanted to give something back to the people: fifty years on and the people are hoping to bring his gift back to live.

The Amulet details

The Amulet, 7 Market Place, Shepton Mallet, Somerset, BA4 5AZ

Architects: Terry Hopegood, with Paul White and Henry Alpass. Wyvern Design Group (Swindon)

Builders: W E Chivers & Sons, Devizes

Client: Francis Showering

Date: 1975

Acknowledgements

I need to acknowledge the fantastic support of Martin and Kai at Let’s Buy the Amulet. They provided me with a draft of the Heritage Impact Assessment which included Alistair Fair’s detailed analysis of the architectural history of the building. They also provided notes and photos from Terry Hopegood’s archive, and quotes from people who used the building. You can learn more about their plans at https://buytheamulet.org.uk/

Amendments

This article was amended on 24 June 2025 with additional information about Terry Hopegood, his drawing of the Babycham building and some additional tweaks. Huge thanks for Kai at Let’s Buy the Amulet for asking Terry some questions for me!

Sources

Rowell, George and Jackson, Tony. The Repertory Movement: A History of Regional Theatre in Britain (Cambridge University Press, 1984)

Alan Baxter Ltd, The Amulet Heritage Impact Assessment, May 2025

C20 backs community plan to revive Amulet Theatre

Holden Brown, Derrick. Obituary: Francis Showering, Independent, 8 Sept 1995

Shepton Mallet’s new town centre official opening today, Western Daily Press, 5 Dec 1975 (£)

Town’s pride fit to bust…, Bristol Evening Post, 6 Dec 1975 (£)