Saltash Library, Cornwall (1963)

Saltash’s miniature Brutalist gem is an exploration of what libraries mean to people, and a history of the mid-century social contract.

“I felt as if I could think clearly there.”

Public libraries are curious places. They are a place to read, to discover, to think. They are so much more than books. They are a refuge, freely offered to everyone. It could be the school pupil looking for a quiet place to study, or the Open University student needing access to books they can’t afford. Libraries used to lend vinyl, and sheet music, even artwork to hang on your wall. A librarian I know hiked through snowstorms in 2018 to open her library: she knew she would be offering a free, warm, dry place for rough sleepers.

Sprinkled across the west country there are mid-century libraries. Monuments, for now at least, to the social contract and the belief that everyone deserved access to knowledge.

I’m taking a deep dive into one such library. A building compared to Le Corbusier and considered “one of the best post-war buildings in the county” in Pevsner.

John Passmore Edwards, the Cornish Carnegie, endowed the county’s industrial towns with libraries in the 1800s. In his time, Saltash had been a small town, one of two ferry sites across the Tamar to Plymouth. The opening of Brunel’s Royal Albert Bridge in 1865 had shorn through the foreshore. Its sturdy, heavy brick legs towered over the riverbank and carried workers from the small station to the work in the dockyards. The bridge carried 140 townsmen to their deaths in World War One and brought the Luftwaffe’s bombs to the town one night in 1941.

By the 1950s, the Saltash ferry, along with its bitter rival the Torpoint ferry just over 2 miles downstream, could not cope with the ever-rising demand for motor vehicle crossings. The national government, struggling to rebuild the transport network as well as the hundreds of thousands of ruined homes, said the Tamar’s crossings weren’t a priority. If Cornwall County Council and Plymouth City Council wanted a road bridge, they’d have to do it – and pay for it – themselves. The councils readily agreed to this act of local devolution and the 1957 Tamar Bridge Act gave them the go-ahead.

Around the same time, a regular anonymous columnist in the Cornish Guardian was campaigning for a better library in the town. The town’s library service was run from a single room in the town council building, which limited its stock to 1,000 books. “With so much being paid in rate-borne levy for the library branch, Saltash can justly claim an improvement in this direction. If only for the sake of the children of the town.” (Cornish Guardian, 27 Jun 1957) He continued to campaign for it in 1958, along with complaining that Saltash was still unable to receive West Country television’s exciting new commercial service.

The government published a report in 1959 detailing the need for more, and more permanent, libraries. Around 350 libraries were constructed between 1960 and 1965. Cornwall County Council’s approach was to create a set of hub sites: small modern branch libraries that also served as a base for library vans that would serve the rural communities. Saltash, with its new road bridge and the promise of a growing population, was picked to have not only a library but an entire civic centre.

Design and construction

Since 1956 Kenneth Hicklin (1915 to 1995) had been assembling a team of young architects at Cornwall County Council. Together they were creating a very Cornish modernism. They built branch libraries at Newquay and St Austell, serving the westernly north and south coasts of the county respectively. These two buildings are the softer, Scandinavian modernism that emerged from the Festival of Britain, now called mid-century. St Austell (1959-60) won a RIBA bronze medal. In 1961 Hickin recruited another newly qualified architect to the team.

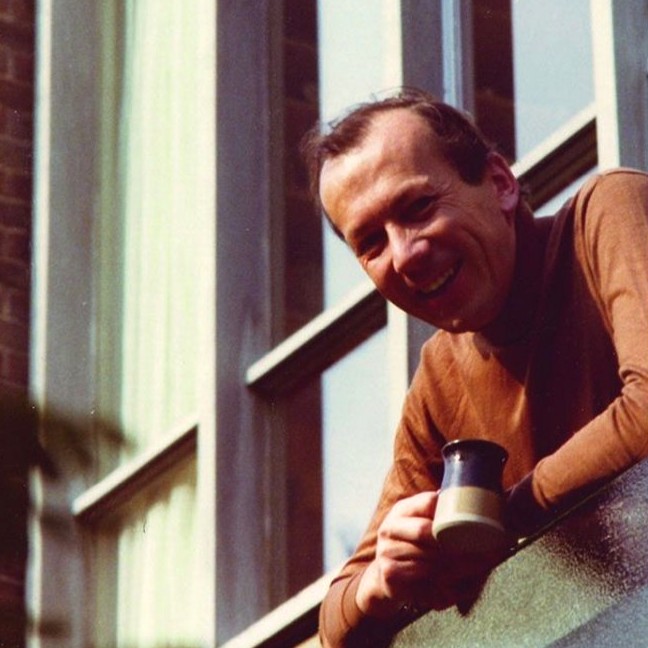

Royston Summers

Royston Summers (1931 to 2012) had been born in Wolverhampton, a butcher’s son. During his National Service in the Intelligence Corps, spying on Russian planes in East Germany, he was shot in the knee. He qualified from the Architectural Association in 1961 and was given the Saltash job as soon as he walked into Hicklin’s office in Truro.

In late 1963 Hicklin left Cornwall County Council, and by 1964 Summers had also quit. Summers moved to London to set up his own practise. He started to specialise in energy-efficient housing, developing passive solar heating. In 1969 he won a medal for Good Design in Housing.

He won the RIBA Architecture Award in 1976 for his work on the Lakeside Drive in Surrey. He designed the first ever solar-heated council flats, in Lewisham, in 1982. Summers died in Bristol in 2012.

The RIBA Journal obituary of Summers describes a man who was passionate about proportions, use of space and appropriate materials. This is all apparent in Saltash Library, his first solo work to be built.

A grand design

Over in India, the Le Corbusier was building Chandigarh, a new civic centre for the Punjab. An entire city was rising to his exacting measurements.

Construction on the Palace of Assembly had started in 1951 and was almost complete when Summers sat down to draught a civic centre for Saltash.

The Library and the Guild Hall of the Cornish town were seen as representing the “enjoyable” functions, so were to be set opposite each other on the sloping site, creating an axis from east to west. The other functions, the Police Station, County Health Clinic, Council Offices and Council Chamber, were seen as “services” that would sit along the axis. The library was at the top of the slope, with its grand western facade facing the rest. The site would flyover the existing road to the junior school to reach the Guild Hall. This civic avenue in the sky was to be planted with evergreens. (Cornish Guardian, 31 Jan 1963)

Summers took inspiration from Le Corbusier, though he chose not to share that with the various committees who had to approve his work. He used Corbusier’s Modular System to create the proportions of the building. And he designed a giant butterfly roof, jutting brutally out over a deep portico of roughly cast concrete. Slender, oval pilottis support it. The library was to be accessed by using a bridge over a shallow reflecting pool that would bounce light, glimmering, onto the underside of the huge roof overhang and its curtain wall of glass. The debt to the Palace of Assembly is hard to miss, if you ignore the cars and railings.

One story I’ve heard, but been unable to find in print, is that the butterfly roof was said to mimic an open book. Like a Cornish giant had just placed his reading on the ground for a moment as he needed to go and throw rocks at another Cornish giant.

One thing I noticed, arriving on a sweltering June afternoon, was that the building turns an almost blank face to the south. That side of the building contains offices and facilities like storerooms and toilets, with small, deep-set windows. This effectively works as a giant brise soleil, keeping the public areas shaded from the midday sun.

The western and eastern elevations were originally all glass with high opening windows. These would catch the prevailing west to east winds, providing ventilation. This fits with Summers’ later specialisation in energy efficient buildings.

Interior

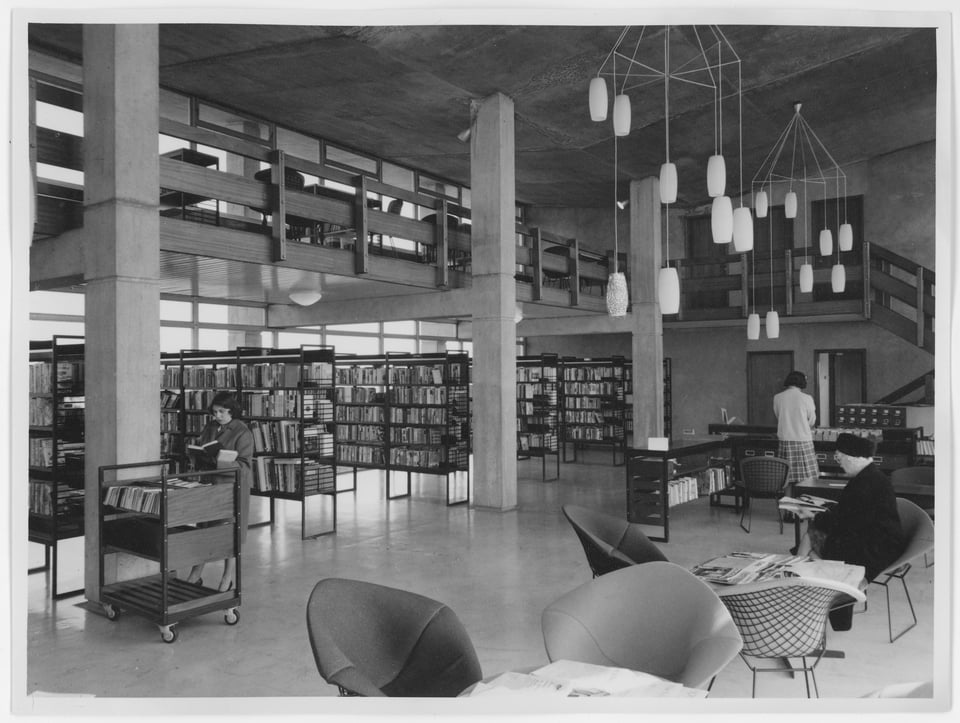

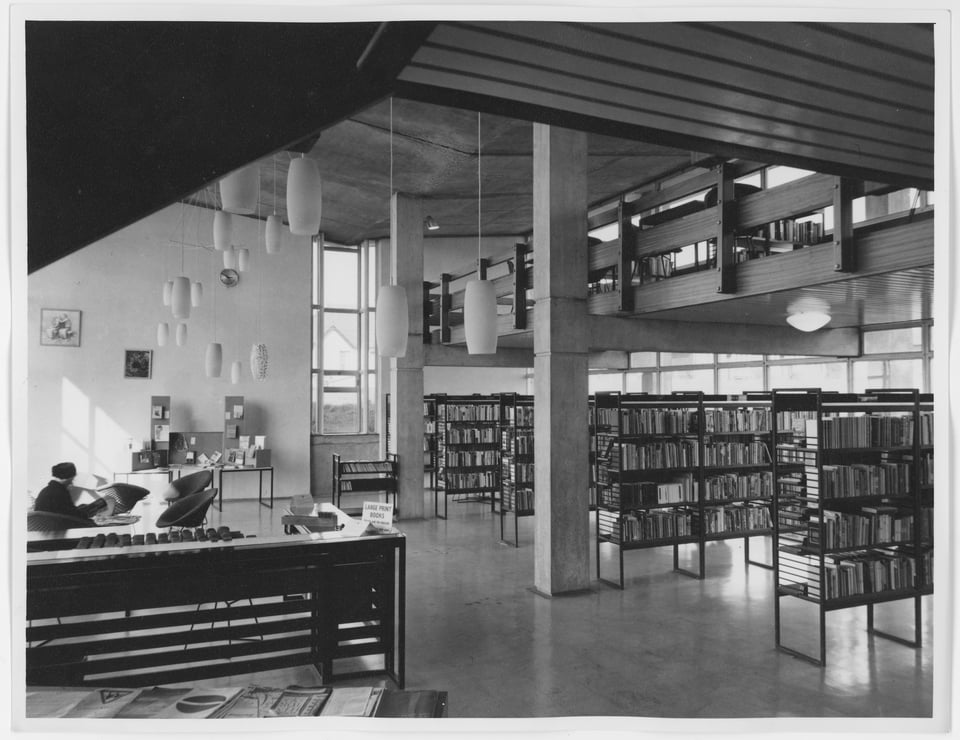

Summers designed a single, double-height open space with small offices against the southern wall. A staircase, still there, led to a “students’ gallery” that crosses nearly the whole width of the building at the ceiling’s lowest point. The H shaped internal frame is clearly visible.

“The upstairs portion was so mysterious for a child: it was serious and academic, as if only lawyers and professors climbed those stairs!” (Facebook user)

This was a typical layout for the period. In May 1956, the architect of Holborn Library (1959) in London, Sydney Cook (1910 to 1979), gave a talk to the Library Association that outlined the principles of natural light, a mezzanine and flexible fittings. Elain Harwood suggested, in the 2016 Historic England guidance note, that these open plans were designed so shelves and tables could be moved to create a hall-like space that allowed meetings and performances after library hours. The layout Summers gave Saltash was thus in line with developing practise, and with what had opened in St Austell in 1960. It could work as a social space until the new Guild Hall, at the other end of the civic centre, was built.

When building work on the library began in June 1962, the most interested spectators of its progress were hundreds of pupils from the adjoining infant and junior schools.

“In the school watching it being built we thought it was going to be a swimming pool.” (Facebook user)

The rough grey concrete exterior and white render interior reflected the Cornish landscape, with the materials brought from the local china clay industry.

Inside, colour and warmth would come from Nigerian walnut bookshelves, tables and balustrades and from the books themselves. Elain Harwood pointed out that the arrival of plastic dust jackets for books meant libraries could keep the bright, colourful paper dust jackets on the stock. Library books were transformed from the muted colours of fabric and board to the bold colours available in bookshops.

Early use

“It was such a treat to go, my dear Dad always put his tie on to visit…we used to tease him about it…guess he felt he should be smartly dressed. The building was so light and airy I also remember the stairs to the second floor fascinated me as a child…they seemed to head up into the sky I always wished I could go up there but I never did. I do also remember the sixties grid metal chairs they had with a thin cushion overlayed to sit on. The height of fashion design at the time.” (Facebook user)

The library opened on 10 December 1963. As part of the opening day’s ceremony, a model of the rest of the planned civic centre was displayed. I’ve not been able to find a photo of that. The connection to Corbusier, which Summers had so carefully not shared with the committees, was part of the local write-up.

“The proportions are based upon the proportions of the human figure according to the Modular System developed by Le Corbusier from a system by the ancient Greeks. Architecturally this helps create a feeling of simplicity and unity.” (Cornish Guardian, 12 Dec 1963)

The branch had 10,000 books: ten times as many as the old room in the town council building. Of those, 1,000 were for children and a further 750 reference books were on the students’ gallery. It was opened by the Chairman of Cornwall County Council, Kimberley George Foster, who said “The future of Saltash may be a little problematical at the moment but I hope that this will quickly become part of the new Civic Centre.”

Foster was alluding to the increasingly challenging situation. The rest of the civic centre was never built, due to budget cuts and the looming local government reorganisation. Instead Saltash Library sat in proud isolation, an isolated Cornish Corbusier outpost, until the 1980s.

A haven for children

Within 3 months, the library had gained 500 new members.

“My friends still tease me about my weekly family visits to the library! I loved the metal door handles and the heaviness of the door as a small child and the smell of books, upstairs remained a mystery, getting stamped was always the best bit.” (Facebook user)

The library was so busy between 4pm and closing time, with school pupils using it to study, borrow books or both, that the librarian, Jack Raynor, had to take on a full-time assistant librarian, Miss K Hocking. (Cornish Guardian, 6 Feb 1964) Its closeness to the infant and junior schools meant it became an after-school space for the younger students.

“My mother, Ruth Harvey used to work there in the mid to late 70s. I used to have to wait inside for her to finish her shift after school at Longstone. Obviously spent most of my time in the children's section. I remember Mr Rayner was the head librarian at the time.” (Facebook user)

Above the shelving, tucked beside the lowest part of the ceiling, the students’ gallery provided older students something the old one-room library could never have offered. A place to think and work quietly.

“It was a very special place for me…I went upstairs to do my homework: there were several desks set up there. It was peaceful and light. I felt as if I could think clearly there without home interruptions. There was also the complete set of the Encyclopedia Britannica and other good reference books.” (Facebook user)

As the years came and went, the students’ gallery enabled others to study as well. By the 1990s, it was offering internet access, allowing long-distance adult learning.

“I finished my Diploma of Community Studies upstairs at the library. I was able to use the internet and get the last of my assignments submitted.” (Facebook user)

The 1960s write-up of its opening mentioned its new offering of newspapers and magazines. One Facebook commentator, who eventually got in to Falmouth School of Art, also loved downstairs.

“Downstairs was a wonderful collection of up-to-date magazines - Studio International and Interiors were my favourites - and contemporary comfortable chairs to sit in and of course a well-stocked selection of fiction books and a request facility. Helpful librarians too. A perfect environment for me.” (Facebook user)

Development

“I would visit the library at least once a week. I borrowed about every computer book they ever had and taught myself to program. I also read my way through their collection of Sci-fi and fantasy paperbacks.” (Facebook user)

The library itself gained an extension in 1992, as the expanding population of the town had outgrown Summers’ original design. This intensely practical single storey addition on the eastern side provides a dedicated space for the children’s library and has various signs of its construction era. The green-enamelled exposed crossbeams practically smell of 1980s leisure services. The plans, which included reroofing, were to cost £250,000. (Evening Herald, 4 Jun 1990) The extension replaced the eastern curtain wall with blockwork walls containing high clerestory windows.

At some point, a central reception desk and interview room was set up in the centre of the building. This is made of wood and plasterboard, slotted within the original 1960s internal frame. This was for when they had a council ‘one stop shop’ on site. Overall, these two changes, both of which make sense from a practical point of view, reduce the natural light and the opportunity for cross-breezes.

Over time the original single glazing in the western curtain wall and the northern bay window had been upgraded to double-glazing. This wasn’t done by replacing the frames, but by removing some of the beading and bedding in a second layer of glass. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the prevailing westerlies loved the gaps and weaknesses this introduced to the huge curtain wall. And the 1960s cable system for opening the high windows, letting in the cross breeze to cool the building, were mostly broken. The building became cold in winter and hot in summer. The windows, their frames stretched and damaged, gathered moisture between the glass, permanently obscuring the view. (Heritage Impact Statement 2022)

Future

Visiting Saltash Library now, the site of the planned civic centre has steadily filled. The open ground visible in the early photos is a car park. To the southwest, down a slope, is a generic 1970s health centre. Beyond that is a 1990s block-built leisure centre, currently being modernised to add council offices. To northwest is a 1980s care home. Each of these have been designed in isolation and in the style of their time. I’d love to see the original civic centre design that never happened.

Unitary and County Councils, like Cornwall, have a statutory duty to provide a comprehensive library service but how they deliver that is up to them. With less money available, ways to reduce the spend on this duty are inevitable. The mid-century splurge of library building is now creating an ongoing maintenance burden. Perhaps inevitably, the BBC estimates 40 libraries a year are currently closing. (BBC) In 1949, Saltash Library was run by Cornwall County Council out of a single room in the town council’s buildings. In 2019, the county council devolved their library building to Saltash Town Council to own and manage.

Two years later, Saltash Library was Grade II listed as a “striking and well-articulated example of post war library design” (Historic England). The town council has since demonstrated its commitment to the building by renovating the windows, with the building reopening in January 2025. They spent £100K replacing the entire western curtain wall, and a further £50K on the other windows. Staff say how much more comfortable the building is to work in now. (Cornish Times) To me this feels like a lovely nod to Summers’ subsequent career in energy efficient housing by restoring his use of natural ventilation and heat capture.

The 2022 Heritage Impact Statement that outlined the best approach to the windows also recommends removing the boxy interview room. It cites advice from the local historic environment officer that includes “the removal of the modern central reception area and interview room would be welcomed as it would return the library to its original open plan proportions.” It would also allow more light into the heart of the building, as the photos suggest.

Upstairs, the students’ gallery holds some seating and some storage. A black metal safety rail has been added above the original Nigerian walnut balustrades.

The days when a reference library was essential is over: the Encyclopedia Britannica is now online. Yet the need for a third space, a free quiet place where a student of any age can sit, read and think, is still there. At Exeter Library (1965) the mezzanine that once held records and sheet music now forms a quiet zone with newspapers, reference books and desks. It’s never empty. It would be lovely to see the students’ gallery at Saltash set up for use again.

I approached Saltash Library from Callington Road, using a small cut through. The library was mostly hidden by a large, spreading pine - perhaps the lone pine to survive from the planting scheme of the never built civic centre? Since the 1960s, libraries have evolved to become self-contained civic centres, and Saltash is no different.

Saltash Library details

Saltash Library, Callington Road, Saltash, PL12 6DX

Architects: Royston Summers, as part of Cornwall County Council’s Architect’s Department

Builders: Carthew and Son Ltd, Downderry, Cornwall

Date: 1963

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the members of the Saltash Group on Facebook for sharing their memories of the library (even the one who explained how to climb onto the roof, which I’m not repeating here!).

Also a thank you to Saltash Town Council and the staff of the library itself for welcoming me in when I visited and providing lots of insight into the building. And to Kresen Kernow for the photographs of its opening reproduced here.

Finally a thank you to Historic England South West for the detailed listing. That, along with Elain Harwood’s write-up in Brutalist Britain, is what drew my attention to the building.

If you are intrigued by Royston Summer’s work, wowhaus has an archive of his residential properties as and when they go up for sale.

Sources

Harwood, Elain. Brutalist Britain: Buildings of the 1960s and 1970s (C20 Society / Batesford Ltd, 2022)

Harwood, Elain. The English Public Library 1945-85 guidance note (Historic England, 2016)

Pevsner, Nikolaus and Beacham, Peter. The Buildings of England: Cornwall (Yale University Press, 2014)

Ramage, John. Heritage Impact Statement Saltash Library 2022

Summers, Justin. Royston Summers obituary, The Independent, 11 Jun 2012

Royston Summers, RIBA Journal, 1 Oct 2012

Historic England list entry 1474413, February 2021

Saltash Mayor Opens Library, Western Morning News, 22 Sep 1949

Better Library for Juniors needed, Cornish Guardian, 27 Jun 1957

New Civic Centre Planned for Saltash, Cornish Guardian, 31 Jan 1963

County’s Most Modern Library Opened at Saltash, Cornish Guardian, 12 Dec 1963

Library Popular with Students, Cornish Guardian, 6 Feb 1964

Talks on £250,00 library revamp, Evening Herald, 4 Jun 1990

C20 Society, Saltash Library listed, 22 Feb 2021

Martin, Sarah. New glass facade makes Saltash Library a warm and inviting space, Cornish Times, 14 Jan 2025

Menon, Stephen and Cawley, Laurence. A library is more than a place with books, it is a lifeline, BBC News, 18 March 2025