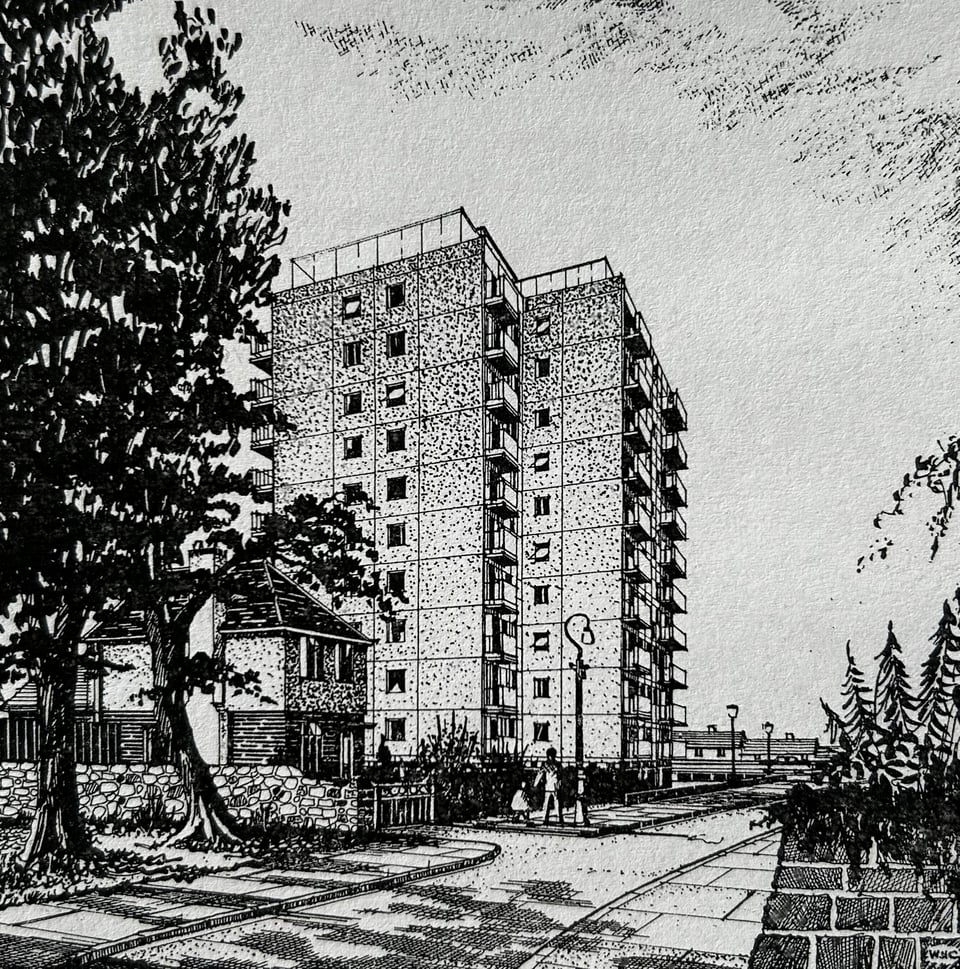

Rennes House, Exeter (1968)

“We used to call it the Mary Mungo and Midge flats.” Taking a look at Rennes House, Exeter’s only council high rise tower block. It’s coming down in 2025, nearly sixty years after it went up.

One day a crocodile of schoolchildren, each carrying a balloon, were led to the tower block that overlooked their playing field. They excitedly rode up in the lift and emerged amid a forest of whirligig laundry lines. Through the glass walls they could see their school far below. They could see their houses from here, and the shops they went to, and the whole city nestled in the bowl of the green fields. They could see as far as the forests of Haldon hills ten miles away. At their teacher’s shout, they let go of the balloons and watched as the wind took them up. Up and away, dancing and bobbing, notes fluttering, until the balloons were out of sight. Over the coming weeks, the letters started to arrive in the classroom saying how far they’d flown from the roof of Rennes House in Exeter.

“Some of the balloons were found miles and miles away. I think about that a lot. My partner’s grandparents were the last ones to leave [Rennes House] in October.”

Rennes House is one of only 15 high rise tower blocks built by local authorities across the West Country. If you come into Exeter from the east or south, on the train from Exmouth or Salisbury, the tower block pops into view, nestled amid the housing estates. It draws – or drew – the eye not because it’s attractive but because it’s unusual for Devon.

The building is a Large Panel System (LPS) tower block of 11 storeys, set within an estate of council houses on what was once farmland and is now an eastern suburb of Exeter. It is scheduled for demolition in 2025.

Construction

Rennes House was designed by Fitzroy Robinson and Partners, a firm more noted for its brutalist office buildings like Sunley House in Croydon (1967) or 102 Petty France (1976, with Basil Spence). It is a simple design, with two interlocked blocks and hanging balconies for each of the six flats on each floor. It was built by Exeter Borough Council and Sleemans using a French LPS method in which the panels were cast on-site.

In Concretopia, John Grindrod describes local authorities embrace of LPSs as a way of providing social housing quickly and at scale. It followed on from the Minister for Housing recommending its use in 1962. Many were 20 storeys or more high. The streets in the sky had arrived.

Rennes House, at 11 storeys, was on a far more intimate scale. The concrete panels have smooth edge frames but are filled with rough aggregate. There is no compromise to the angles.

According to people who were involved in – or watching – the construction of Rennes House, the problem with this specific LPS became apparent quickly.

“When it got to 5 stories, they noticed the foundations cracking and had to stop going up and reinforce the pillars. The builders imported the crane from France but British builders were still using imperial so the crane didn’t fit the rails and it had to be re drilled.”

Another worker remembers the efforts to get the slabs to dry.

“I worked for Colston Electrical, I recall having to put the conduit in the slabs, had to be accurate, I seem to remember they had hot air blowers to dry out quicker.”

This explains a curious detail in the annual reports of Exeter’s City Architect. In the report to March 1966, there is an optimistic view with preparations well advanced to build the block (then called Whipton Barton Farm phase 2). And in the March 1968 report, the City Architect is very enthusiastic about the final block, now named Rennes House after Exeter’s twin city in France:

“After a slow start this high-rise block of flats is now nearing completion. It has been a most interesting scheme from the structural viewpoint and the final appearance of the building is most pleasing and in my opinion a step forward from the usual general characteristics of tall housing units. The research in this project will benefit others where such schemes are under consideration.”

Yet in the 1967 report, there is no mention of the block at all. This fits with the anecdotes that the builders quickly found a problem constructing it.

Within months of the City Architect’s positive write-up, the LPS Ronan Point block in London suffered a catastrophic failure. It seems likely that, faced with a combination of their own construction experience and the Ronan Point collapse, the city lost its appetite for high rise living. The one tower block they did have needed to be made safe.

“Rennes House was half gas and half electric and following the Ronan Point gas explosion all the gas was removed. I remember installing electric cookers in the flats that lost their gas cookers. I had just started as an apprentice electrician at the time.”

Within a year the waiting residents had moved into Rennes House. A delegation from France visited and revealed a name plaque as well as meeting the first residents.

Life in Exeter’s only high rise

Rennes House, along with the rest of the buildings on the old Whipton Barton farm site, was always intended to be housing for older people. Next to it was a complex of 11 bungalows connected by covered walkways to a Welfare House containing 24 one or two bed flats in four storey blocks. Some of the people moving into the estate had come from the pre-fabs that had sprung up to house people whose homes had been bombed.

“My nan Kath Riggs lived there from new. She moved from the old pre-fabs near Whipton bypass. She lived at no.22 4th floor looking at Whipton shops from the kitchen window. Good memories as kids using her binoculars to spy on the shops.”

“My nan Rose and auntie Doreen were one of the first residents. Flat 28 on the fifth floor. Nan died in 1982 but auntie stayed in the flat until she passed away in 2018. …All four of us grandchildren/ nephews would leave our bikes in the lobby after coming in the ‘back way’.”

Rennes House was right next to Whipton Barton infants’ school and surrounded by housing. The kids called it “the Mary Mungo and Midge flats”. From people’s memories, the location made the whole Whipton Barton estate part of the community. The school would organise trips to the tower.

“I can remember a school trip over to see Mrs Turpins (a dinner lady in the infants school) Mynah bird. Then we went right up to the top of the building.”

“That was my Gran, Margaret she lived on the ninth floor with my Grandad Sidney. The bird was called Jason and mimicked her voice perfectly. Writing this has made me realise how much I miss those times and sitting in their kitchen watching the trains on the Exmouth line.”

As well as the laundry room and drying area on the eleventh storey roof, there was a social area on the ground floor.

“My Nan and Grandad Viv and Babs live on the 9th floor No.50 there was a residence social room on the ground floor and a members social fund, they used to have parties & afternoon teas, there. They held bingo sessions and whist drive evenings, and also arranged outings l think once a month. Grandad sadly passed away in 1989 and Nan lived there until 2015, when she was in her 102nd year when she sadly passed. She had a lunchtime party to celebrate her 100th Birthday in the social room, the lady Mayor came and presented her with a card and gift from Exeter City Council.”

The social room was clearly where it all happened. Although not every resident loved it.

“There was a communal lounge that [nan] rarely used as at 80 plus "They are all old folk in there”!”

A council survey of the tenants in 2018 confirmed that they liked living in Rennes House for the location, size of flat and sense of community.

The end of Rennes House

In the 1980s, the window frames of Rennes House had to be replaced. By 1992 the heating had been switched to storage heaters, and asbestos tiles had been removed. There was still a problem with water penetration. This is a recognised issue with LPS structures. The heating system was upgraded again in 2011, but the costs of heating stayed high – around £1,000 a year for each flat in 2018 according to a 2022 options report on the building.

In 2016, the council carried out a feasibility study for refurbishing Rennes House. This included increasing the strength of the ties holding the panels to the frame, improving insulation including external wall insulation, refurbishing the lifts, remodelling the ground floor and removing the last of the asbestos.

Then the horrific fire at Grenfell happened in June 2017. It required all authorities to identify and risk assess their tower blocks. Exeter City Council provided assurances that Rennes House was safe. They also continued the refurbishment plans, replacing the lifts.

And then the COVID-19 pandemic began. Life in the block during the lockdowns was tough. The local paper visited, carefully, and captured life there. The social activities were all put on hold and a no-contact system was put in place for sharing DVDs by putting them on a bench outside.

“On the whole we are a pretty independent lot here, and people are carrying on the best they can…. People living here have been chatting from their balconies and are sticking to all the rules.”

“For a block as big as it is, Rennes House is a really good place to live. It might be a bit ratty and tatty, but it has a lot going for it."

An options paper in early 2022 confirmed that the costs of refurbishment had risen, whilst the “management of high-rise blocks is becoming increasing complex”. No amount of retrofitting would make Rennes House as energy efficient as the Passivhaus new builds the council was committed to building. The rest of the estate – the bungalows and welfare house – were already being demolished and rebuilt to twenty-first century standards. And underlying it was the fear of a fire or a structural failure, with residents unable to safely get down the lone staircase. The council decided to demolish Rennes and provide new homes for its tenants. The local paper went back to talk to residents again.

"I'm devastated. It's my home and I don't want to go. I don't care what it looks like from the outside and I get upset when people say it's an ugly building. It's home and I feel safe here, and I will miss the familiarity and the views.”

“I will definitely feel sad when I move out but it's not the same as we don't have bingo nights anymore. Now I don't even go in the communal lounge because so few people are still here."

By November 2024, the last residents had been moved to alternative homes. By December, the strip out had started ahead of demolition.

What comes over, from people’s memories and reporting from the pandemic, is that generally people loved life in Rennes House. Some residents who moved into the block in the 1970s were still there in the 2010s. But the building had reached the end of its life, as buildings of all eras do. To retrofit it would cost as much as to start again.

There was nothing special about Rennes House from an architectural view. Nothing innovative in its design that would mean people would campaign to save it.

There was nothing special about Rennes House, except to the people who called it home.

Rennes House details

Rennes House, Vaughn Road, Exeter, EX1 3JW

Architect: Fitzroy Robinson and Partners

Builders: EBC and Sleeman

Date: construction started 1966, occupied by 1969.

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to all the people who responded to my Facebook requests for memories of life in the flats in the 1970s. It was wonderful to see people connecting in the comments, and to get first hand accounts of its construction. The posts are on the Exeter Memories and Exeter Past and Present.

Thank you to Anita Merritt at Devon Live for permission to use her photographs of the inside of Rennes House, and for all her work reporting on it over the last ten years. Links to her articles are in the Sources section.

If you have enjoyed reading this, you can subscribe. Paying subscribers will get early bird access to future deep dives.

Sources

Eduardo Hoyos-Saavedra, Discovering Exeter 11: Twentieth-Century Architecture (Exeter Civic Society, 2001)

Miles Glendinning and Stefan Muthesius's 1994 'Tower Block: Modern Public Housing in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland'. Courtesy of https://www.towerblock.eca.ed.ac.uk/resources/tower-block-books

John Grindrod, Concretopia: A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain (Old St, 2014)

Report of the City Architect for year end 31 March 1966, Devon Archives and Local Studies ref 5122A/21-20

Report of the City Architect for year end 31 March 1968, Devon Archives and Local Studies ref 5122A/21-20

'Devastating' evictions served at Exeter landmark tower block by Anita Merritt, DevonLive

These Four Walls: The reality of lockdown life inside Exeter's Rennes House tower block by Anita Merritt, DevonLive

I visited Exeter's iconic tower block and was left shocked by its demise by Anita Merritt, DevonLive