Lys Kernow (New County Hall), Truro (1966)

A very Cornish brutalism sits just outside Truro. I take a look at the ambitious work of a County Architect who had a vision of the future.

It was a thundery spring, the year everyone moved into the new county hall above the city. The men tasked with the move, seconded from the cleaning team, stood under the crumbling doorway of the old building and waited for the torrential rain to stop so they could load another department onto the vans. A few days later, as the council met for the first time in their cantilevered, copper topped chamber, the storms rolled overhead. Hail hammered down, drowning out the speeches.

“The building was so modern after the old building and very advanced in technology.” (Facebook user)

Next year, Lys Kernow in Truro will mark its sixtieth birthday. Originally known as New County Hall it was renamed in Cornish in 2009. It’s one of several mid-century County Halls around the West Country but is the only one to have embraced modernism in its full concrete brut form.

This month, my deep dive looks at the ambitions of a team of young architects, and how the wildest west country responded to a modern municipal masterpiece emerging from the playing fields.

A very Cornish modernism

In 1956, Francis Kenneth Hicklin (1915-1995) was appointed as the County Architect for Cornwall. Hicklin had joined local government in 1938 in his native Derbyshire. During World War 2 he’d joined the Royal Engineers, rising to become a major in charge of rebuilding railway bridges. Back in civvies, he became chief assistant to RIBA President Charles Aslin at Hertfordshire County Council. Hicklin then returned to Derby in 1949 as assistant County Architect where his main work was building the new schools urgently needed for the baby boom.

When Hicklin got to Cornwall, he started developing a team of young, newly qualified architects around him. There was a focus on schools and libraries. He and his team designed Treyew Infant School as a series of interlinked hexagons. Their St Austell branch library in 1959-60 won a RIBA Bronze medal in 1961. His team included AHM Linscott, KMG Kirkbride, JR Coward and R Summer. Royston Summers would go on to design the Grade II Saltash public library for the county.

The buildings created by Hicklin’s team show a strong engagement with, and commitment to, a modernist worldview. Jonathan Meades has called brutalism “more a mood (of high optimism and humankind’s celebration of itself) than a style” (Literary Review). I wonder if Hicklin, who had spent three years literally building bridges in post-war Europe, led his team with a determined eye on building a better future.

Hicklin had also been tasked with the problem of housing the council itself. Cornwall County Council had long outgrown its existing Edwardian building in Truro, with hundreds of staff crammed in. People overflowed into temporary buildings in the carpark and scattered sites across the city. In fact, the 1960s chair of the council reflected that the old building had been too small when he had first become a council in 1937 and another councillor called it a slum (Guardian, 21 April 1966).

By 1960, Hicklin was consulting with Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe (1900-1996), who was already working with Totnes Town Council and Plymouth City Council. They presented the council with a proposal in June 1960. Jellicoe recommended against building in the centre of the city. Any such building would be on a constrained plot and the subsequent verticality needed to fit hundreds of staff would destroy views of Truro Cathedral.

The team proposed a new site, just above the railway station and the existing county hall. They would build a grand design: a modernist country estate set within sloping, naturalistically landscaped grounds.

Design

In October 1960, the team took a tour to Denmark to see the various town halls of Jellicoe’s fellow landscape architect Arne Jacobsen. Jacobsen’s Rødovre Town Hall had been completed in 1956 and was an example of his total control approach. As well as designing the building and grounds, he designed the fixtures, fittings and furnishings. By 1962 Jacobsen was even specifying what fish could be put in the pools at his building for St Catherine’s in Oxford. This total approach seems to have inspired Hicklin: he and his team tried to design everything from the ground up.

“The architects decided to try to create a sense of community within the building itself by disposing the accommodation around a central courtyard.” (Architect’s Journal, 1966)

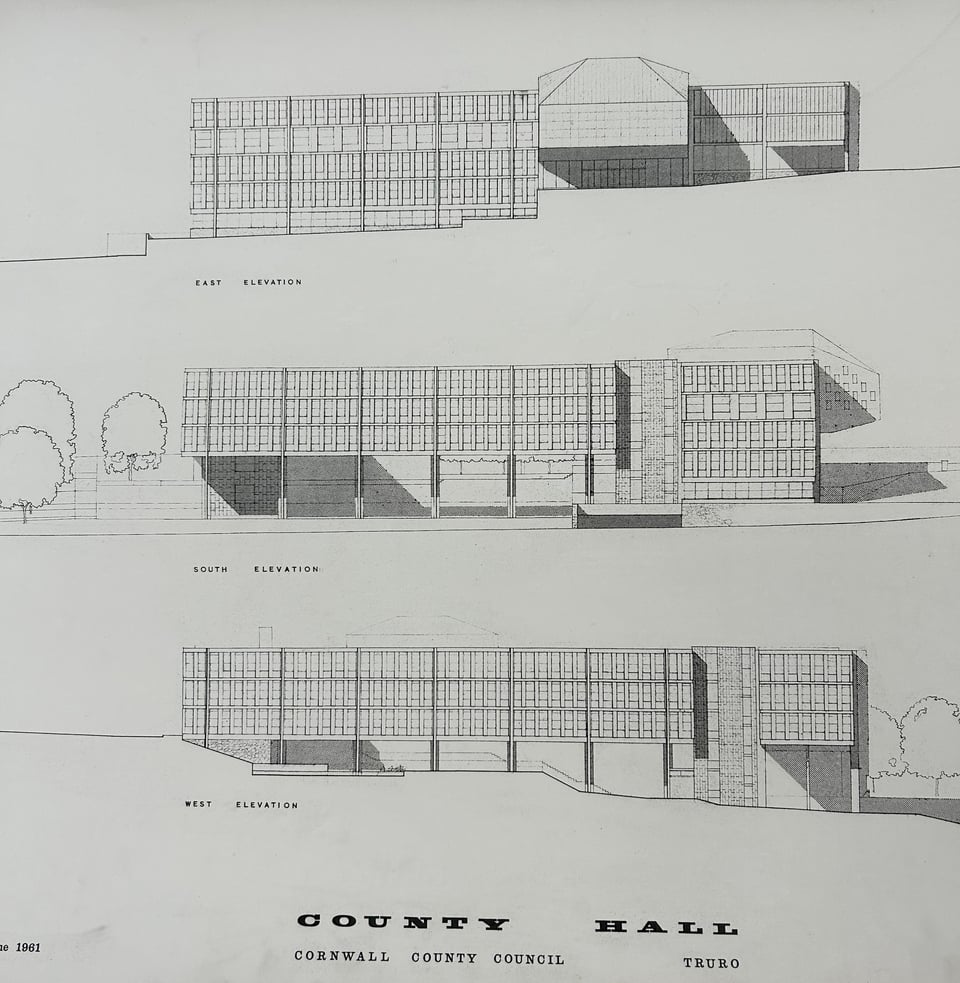

The building forms a large quadrangle about a multi-terraced courtyard complete with reflecting pools and a modern sculpture. At the northern side, facing the city, it presents a single, anonymous, three storey block. The main frame is on a 30-foot grid. Within that, everything is on a 5-foot grid. The rigid clean lines of the original drawings are ruined by modern additions, though none break the low skyline.

But move to the south, overlooking the drop to Penweathers, and the three storeys that skulked low on the ground are now high in the air, hoist far overhead by slim, rough cast concrete pillars.

Standing within the courtyard, even with the reflecting pools drained to allow for some work to be done, and the green beyond the building draws the eye. Down the slope, towards the valley thick with trees. Even the coffered underside of the raised floors glows green.

In their 1961 detailed booklet, the team explain their design approach, saying, “the principle of using indigenous Cornish materials externally on the buildings and in the paved areas will also apply to the choice of species for use in the landscaping” (CC/AG/1, Kresen Kernow).

“Cornwall’s is a granite landscape, with few buildings of brick, and heavy concrete and render fit in well – aided by a substantial cement industry in the county.” (Hardwood)

Where most Brutalist municipal buildings landed in urban town centres only to fight the existing history, Lys Kernow was designed to blend in with the rocky, steep and brutal landscape of Cornwall itself.

“I remember seeing it being built from the grammar school opposite. It was quite controversial at the time but I remember our chemistry teacher saying how much she admired it because it fitted with the contours of the land rather than being prominent on the skyline.” (Facebook user)

The one break in the strict concrete repetition of the external grids is the council chamber, which is cantilevered out of the eastern side of the building and presents an utterly blank polished Derbydene stone face to the world, with an unbroken copper roof acting as a shell.

Only when you look at the sides of the chamber, craning your neck upwards, do you see small windows in a checkerboard pattern. They seem far too small. The block of it breaks the courtyard lines too, with a face pierced with small windows like a row of gunners’ slits. The shape of this block, the chamber and its associated spaces, is like a giant tank has climbed up and broken into the orderly rows.

The ceremonial approach to the building was from the northeast, so that the huge bulk of the council chamber loomed overhead. Even at the time it opened, the AJ pointed out that most staff and visitors would actually approach from the terraced carpark to the west or the road up from the station.

Inside, partition walls were designed that could be moved to reallocate space as needed. Early ideas around concrete partitions were changed during construction, and glass walls were used instead.

“I worked in the Clerk’s Dept in the old county Hall in early 1960’s and remember moving up to the new Hall. The glass walls to the offices took a bit of getting used to! (Facebook user)

Construction

Construction began on 1 April 1963, with local contractors E Thomas. The turf was then symbolically broken in May 1963.

“My Grandad worked on this building… there were two big yellow cranes running on rails as I can remember when he took me there.” (Facebook user)

“My Father worked on this building and a small part of it collapsed on him, he nearly died and spent months in the old City Hospital. He had broken legs and ribs etc.” (Facebook user)

In October 1963, Hickin’s retirement on medical grounds was announced. The council agreed to pay him a consultative fee of £1,500 a year to advise on the completion of the county hall.

“I think we have been extraordinarily fortunate to have had his services although only for seven years and it is remarkable how he has changed the face of Cornwall during that time,” said a Mrs E V Townsend. (Guardian, 7 Nov 1963)

The rumours were Hicklin had fallen out with the councillors over the internal furnishings of the hall, but the external cladding only began to be laid in June 1964. All the coverage of arguments about the furniture are also from 1964 onwards. As is the argument about the courtyard sculpture.

In 1965, the council agreed to pay £3,000 for Rock Form Porthcurno by Barbara Hepworth. The asking price for the bronze sculpture was £9,000, but Hepworth wanted her work at the hall and offered a very hefty discount. The decision to buy it caused angry debate, with some councillors thinking the rates should be spent on housing and schools rather than artwork.

The chair stood firmly on the fence. “Whether we like her type of abstract sculpture or not, we have to consider what is best for posterity, in laying out this County Hall” (West Briton, 11 Nov 1965). The same day, the newspaper reported that A J Groves, the assistant City Architect in Sheffield, had been appointed as the new County Architect. His salary provides a useful context for the debate about the Hepworth, as it came in at £4,220 a year (or 1.3 Hepworths).

A working building

The first council session was held in the new chamber on 10 May 1966. The local paper, the Cornish Guardian, carried news of the meeting and how satisfied the councillors were with their “impressive amphitheatre” (Guardian, 12 May 1966). But a later write up suggests some challenges were also revealed that day.

“At the first council meeting in the new building on a very warm summer’s day a truly frightening thunderstorm raged overhead, and the sound of hailstones on the metal roof sometimes made it difficult to hear. The afternoon sky was so dark that all the many lights in the Chamber were turned on producing an unexpectedly high temperature that caused concern to one or two aldermen of very advanced years.” (Dennis)

The building was formally opened by Queen Elizabeth II in July. Photos from the time show a starkly modernist courtyard devoid of the mature planting that now makes it charming. As part of the opening events, Dame Barbara Hepworth was waiting in the courtyard alongside her sculpture (Guardian, 21 July 1996).

Staff had already moved across from the old County Hall to the new one back in April 1966. (Guardian, 21 April 1966).

The new building was equipped with the latest computer technology: an ICT 1901 which was due to not only do all the accounting work for the Treasurer’s department but “routine clerical processes”. A photo of just ahead of the formal opening shows a woman sat at a desk in front of six reel to reel computers. Microfiche scanners and readers were set up to reduce the volume of paperwork that needed to be kept. (Guardian, 21 April 1966)

Each floor of the building had a different colour of Armourtile flooring: a classic way of helping people navigate modern buildings. The specific lino used had been developed in the early 1960s to be tough enough to cope with stiletto heels (Guardian, 21 April 1966).

“When we moved up to NCH I was put in the typing pool. Great times. The building was so modern after the old building and very advanced in technology. Beautiful IBM electric typewriters and a central dictaphone station where departments could pick up their internal phones and dictate their correspondence which was transferred to an L.P sized brown disk covered in a magnetic surface. Great memories. We were right next to the canteen so it was very convenient for lunch! There was a cigarette machine on the lower ground floor where I used to go and buy 10 Richmond! It took ages to navigate my way there!!” (Facebook user)

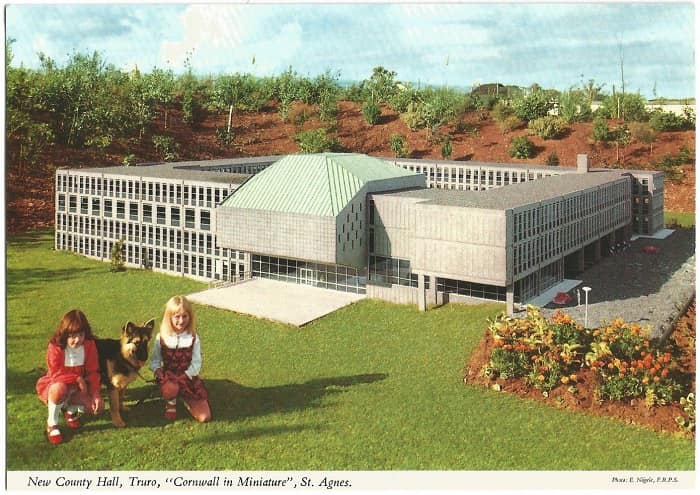

By 1973, the building was sufficiently well known that the St Agnes Model Village included a version of New County Hall.

Lys Kernow today

In 1990, the original approach to the building from town was altered so a lot of the impact is lost. Only a footpath from the neighbouring Lidl supermarket still takes that route. Even then, the mature trees hide the impact. Instead, the approach is now from the northwest. From here, with the chamber hidden, it looks like nothing more than a generic 1960s low rise office block. This was described in 2008 as “the triumph of the road planner’s art, working out ideal geometries for cars and lorries but making a new place of immense ugliness and inconvenience for all other users” (Gould & Gould).

Since 2013, southwest architects Poynton Bradbury have made changes to the building to solve accessibility issues that had not been considered in 1966. These restored the main entranceway under the overhanging council chamber but could not do anything about the ruined approach.

In 2022, gull winged solar arrays were added to the northern carpark, further diminishing the building’s formal lines from the north. Combined, these mean Lys Kernow is deeply unimpressive when I approached it on foot from the train station. But then I explored it from every other angle, and it is stunning.

The planting in the courtyard has matured, creating dancing dappled shade. From within, looking outwards, the scale of the building and the open side to the south mean it doesn’t feel mean-spirited or closed in. The outer surfaces are aging, as should be expected after sixty years, but the weathering works because of the decision to use local materials. The Hepworth sculpture has aged, gaining the distinctive weathered patina of her work.

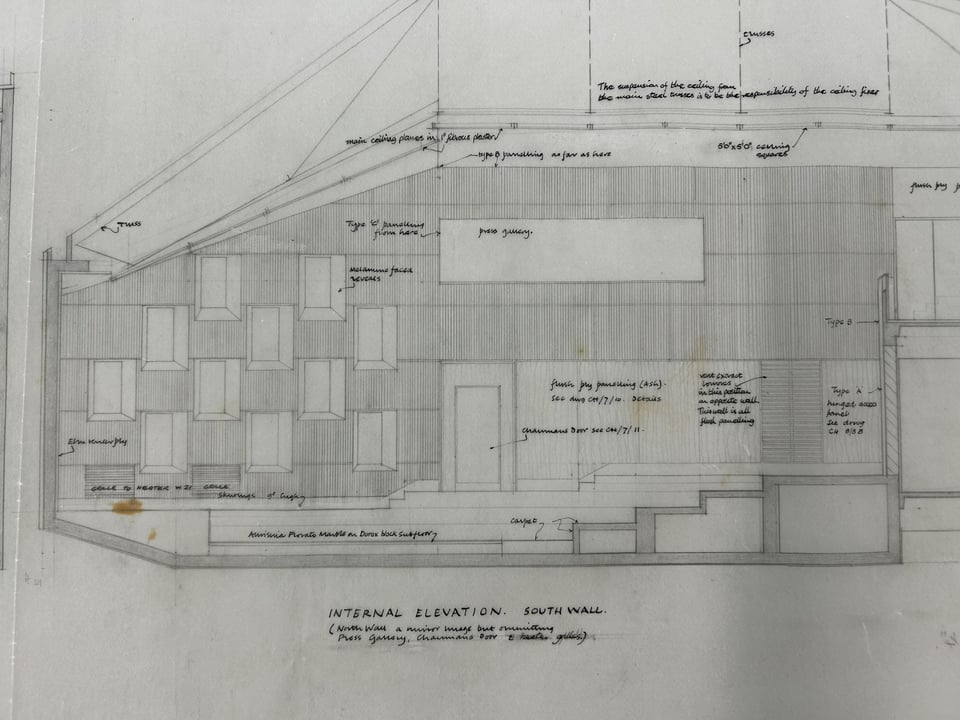

Internally, large parts are intact, including the terrazzo flooring and pearwood panelling. Stepping inside the council chamber on a hot April afternoon, the air was thick, and I could well imagine the elder statesmen feeling overcome by the heat back in 1966. The revelation of the chamber is the light. From outside, the chamber looks like a fortress. Inside, the light streamed in. It illuminated the dais with its giant Union and Cornish flags, and its circular amphitheatre.

Back on the ground floor, modern flexible workspaces have been added with care. Apart from one white plastic pocket socket that for some reason is placed in the centre of a polished black marble wall.

With some of the twentieth century buildings I’ve written about, I’ve suggested they have had their time. With Lys Kernow the Brutal exterior and Scandinavian interior that was criticised by the Architect’s Journal when it opened now work together to provide a certain flexible timelessness.

The twenty-first century changes have used modern takes on mid-century furnishings that complement the original interior without attempting to turn back the clock. The biggest challenge the building faces is its poor environmental performance and the continual tightening of local government budgets.

The costs of upgrading Lys Kernow are set to be more than £11million. The upgrade will tackle the current poor energy performance by replacing windows that have been there since 1964, as well as replacing the gas-powered heating. Just as the original building was contentious, the refurb is being heavily criticised.

Back in 1963, Hicklin retired from Cornwall and headed back to Derbyshire. There he joined a private practise and resumed designing radically modern schools, such as Holywell in Loughborough and St Matthews in Darley Abbey (Derby Evening Telegraph, 30 Jun 1973). He died in 1995.

Three years after his death, Lys Kernow was listed as Grade II.

Lys Kernow (New County Hall) details

Lys Kernow, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY

Architects: Francis Kenneth Hicklin and Alan Groves, with landscape and courtyard by Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe.

Builders: E Thomas & Co, Falmouth

Date: 1966

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the staff at Lys Kernow, who let me look around the inside, including the council chamber, as well as the outside of the building. Even walking into the courtyard from the reception provided a different perspective.

Also thank you to the archivists at Kresen Kernow in Redruth for retrieving the plans and paperwork for me, and giving me permission to reproduce a couple of my photos here. Also, the Hungarian flatbread special at the café was superb!

Finally, a huge thank you to the people who offered their memories of the building over on Facebook and the admin for not taking the post down despite someone seeing it as a way to make political points.

Sources

Beacham, Peter and Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Buildings of England: Cornwall (Yale University Press. 2014)

Dennis, A L (ed), Cornwall County Council 1889-1989: a history of 100 years of county government (CCC, 1989)

Gould, J. & Gould, C. New County Hall, Truro. Listed Building management guidelines (2008), quoted in Morris.

Hardwood, Elain. Brutalist Britain: Buildings of the 1960s and 1970s (C20 Society / Batsford, 2022)

Morris, B., New County Hall, Truro, Cornwall Heritage Impact Assessment (South West Archaeology, 2022)

Poynton Bradbury Wynter Cole Architects, Cornwall Council Property Estate Transformation New County Hall Internal Alterations: Heritage Impact Assessment, March 2024

Historic England: New County Hall including Terrace Pool Surrounds and Bridge to Courtyard

RIBA pix catalogue of 1960s images

Poynton Bradbury New County Hall projects

Meades, Jonathan. Castles of Concrete, The Literary Review, May 2022

Photographs, New County Hall, Truro CC/AP/9/3, Kresen Kernow

Plans, New County Hall, Truro CC/AL/2, Kresen Kernow

Brochure, New County Hall, Truro CC/AG/1, Kresen Kernow

Architect's Journal, New County Hall, Truro, CC/AG/2, Kresen Kernow

Architectural plans, New County Hall, Truro, CC/AL/4, Kresen Kernow

Photographs, New County Hall, Hepworth Sculpture, CC/AP/9/5, Kresen Kernow

Cornwall’s New County Architect, The Cornish Guardian, 16 Feb 1956 (£)

County Architect has retired, The Cornish Guardian, 7 Nov 1963 (£)

Council to pay £3,000 for bronze sculpture, The West Briton and Royal Cornwall Gazette, 11 Nov 1965 (£)

New County Hall Comes to Life and Activity, The Cornish Guardian, 21 Apr 1966 (£)

First Speech in new County Hall praises Chairman, The Cornish Guardian 12 May 1966 (£)

Splendid Scene at New County Hall, The Cornish Guardian, 21 Jul 1966 (£)

New School Will be Aluminium Hexagon, Derby Evening Telegraph, 30 Jun 1973 (£)