Field Notes: University of Exeter (25 Sept 2025)

The University of Exeter's campus reveals a lot about how the institute projected itself from the 1920s through to the 1970s. Who's up for an autumnal wander around it?

It’s a new term, so here’s a wander around a university campus. I did this at the start of September, just as the very first students were arriving.

The weather is sunny down here, so I’m hoping to sneak in one or two more field trips before the skies turn. Time to get out the cardigan and settle in for an autumnal walk.

University of Exeter field trip

This field note looks at some of the 1920s to 1980s modernism on the University of Exeter’s Streatham campus. The uni also has campuses at St Lukes, across town from Streatham, and at Penryn in Cornwall. Streatham is the main campus and went through a major expansion twice during the twentieth century. I only looked at the buildings and not the halls of residence. This isn’t a complete guide to everything, just what snagged my attention.

Before we start, I want to acknowledge my two main sources:

Eduardo Hoyos-Saavedra’s Discovering Exeter 11: Twentieth Century Architecture (Exeter Civic Society, 2001)

Tony Stokoe’s planned route for a C20 Society tour ten years ago.

The University of Exeter started out as a college (or three) scattered across the city. In 1911 they consolidated into a purpose built Edwardian Gothic building, Bradninch Place. Designed to accommodate “over 300” students, it began to burst at the seams after World War One. By 1922 the University College of the South West had bought up 120 acres of farmland from the Streatham Estate to the north of Exeter. It’s a hilly, south-facing site, with two streams zigzagging through it and a third separating the campus from the town.

According to Hoyos-Saavedra, the University College appointed two architects to draw up a scheme for the site. Sidney Greenslade (1867 to 1955), originally from Exeter, was a classicist who had won the competition for the National Library of Wales. E Vincent Harris (1876 to 1971), originally from Plymouth, was another classist who never got on with the modernists.1

Harris’s symmetrical schematic, with a grand avenue from north to south and buildings neatly arranged, never happened. In 1953, just before the University gained its charter in 1955, Sir William Holford (1907 to 1975) was appointed university architect and his plans for the site work more sympathetically with the slopes and streams of it. Holford was a modernist, to the extent that he liked Le Corbusier and had taken over from Abercrombie as Professor of Town Planning at UCL in 1948.

This tension - between the desire to give the University the gravitas of the establishment and the desire to look ahead - plays out on campus.

I walked up from the river to the west, which gives a strong sense of the steep slope. The turning onto Streatham reveals old lodge houses, and the Edwardian villas of Streatham Rise. Then the road emerges from the trees to reveal the first visible building.

Washington Singer Building (Vincent Harris, 1931)

This building is what I think of when I hear the phrase ‘redbrick university’.

It’s simultaneously too plain and too muddled. The gazebo style porches’ pyramidal roofs hide the detail of the longer windows that break up the facade.

Harris’s 1940 Roborough Library is hidden by the Washington Singer and Old Library buildings, to the extent that it’s very easy to miss it. Its three double height bay windows have stone casements facing onto the lawn that are charming and remind me, oddly, of the grand windows at Castle Drogo (Sir Edwin Lutyens, 1930). But we’re still very much in the realm of a streamlined traditionalism – especially if you compare this to the ruthlessly moderne college campus the Elmhirsts were building at Dartington during the same period.

I always feel like the pre-war campus buildings borrow the robes of early C20 colleges at Oxbridge and the Ivy League to give the then University College of the South West more gravitas.

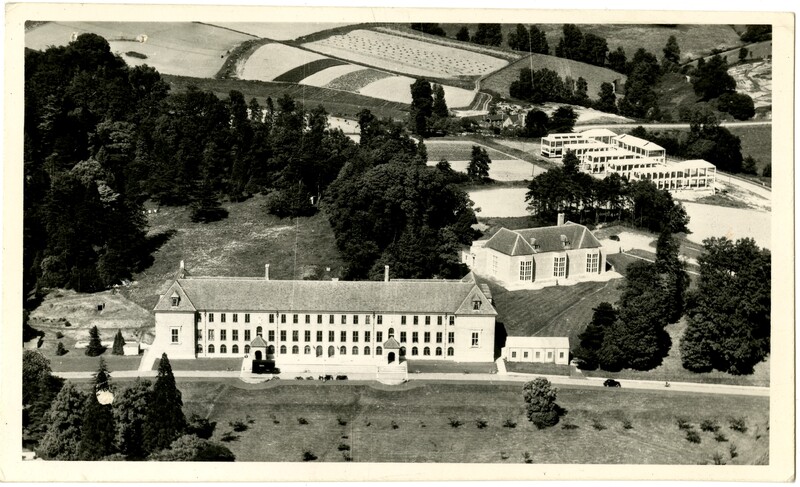

Here’s an aerial shot of Washington Singer and Roborough in the late 1940s, with the Hatherley Building (Vincent Harris, 1952) under construction.

I ended up doing the campus in a rough clockwise loop, turning left from Washington Singer.

Figure for Landscape (Barbara Hepworth, 1960)

This bronze is one of seven made of this work, and others I’ve visited are at St Ives in Cornwall and Washington DC. This Hepworth, with its hulking outline, the bronze hugging the statue’s own void, always feels disconcerting to me.

The university have positioned this one among the trees, which adds a certain amorphous alienness to it, like glimpsing something from another time.

Queens Building (William Holford, 1958)

We’ve reached the post-war period now. Holford casts aside Harris’s monumental plan in favour of building with the landscape. This shows in this side elevation of his Queen’s Building, where the cast concrete foyer block sits on a levelling rubble wall base.

Queen’s forms a set of courtyards and quads with Devonshire House (Holford, unknown date) which is the main Guild of Students building. It’s a perfectly pleasant student’s union, with some nice 1960s touches: I vaguely recall a straightforward 1960s iron balcony railings from the days when I used to go to the SFF soc there. Above Devonshire sits one of the iconic vertical structures of the campus.

Northcote House (William Holford, 1960)

The building itself is a curious mix. Almost entirely redbrick, with some pleasant bays and a diamond pattern faintly visible in the mortar of the brickwork. I’m flagging that now it’ll become clear this is Holford’s signature hatching.

There’s also a block that seems slightly out of time and suggests a 1970s addition. It was, as you can see, badly backlit. The pattern of staggered bays with windows set into one side is something we’ll see again, and makes me think this is still Holford.

But what really draws the eye about Northcote House is the clock tower. This brick clad tower rises smoothly up to where four square clock faces sit between simple stone obelisks and the whole topped by a turret and weathervane. Hoyos-Saavedra describes the clock tower as exquisite and also reveals its secret: Until 2001 at least, the tower held the water supply for the campus.

The wind was indeed coming from the west, and later photos will show what that means in the west country.

By the 1960s, the newly chartered university was expanding rapidly, and a lot of new buildings were underway under Holford’s aegis.

I’ll circle round to Holford’s other designs in a bit because first we’re going further up Queen’s Drive to see my favourite C20 building on the campus. At the junction of Queen’s Drive and Stoker Road, a short step left reveals the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies (LHC Design, 2001). From its fountain, you get a clear view of the modernist heart of the 1960s expansion.

Physics Building (Sir Basil Spence, 1967)

I live a couple of miles from this elegant building, but I see it clearly most days. Its slender bands of vertical aluminium fins catch the light from dawn to dusk, like a sentinel over the city. From my side of town, the tower rises out of the tree-clad hillside of the campus.

Up close, it’s an entirely different mass. It seems to float over the building’s brick-clad base. Spence used two forms for the building. The long two storey brick block is solid, set firmly into the slope. Then the tower suspended above, its supporting core almost hidden from every angle.

It’s like its defying the very subject studied and researched within it. Form following function but playing with it. Even the porch is cantilevered out as a mass. This is statement architecture at its best.

Though I suspect generations of students may have views on it as a practical space to work. I bet the lift used to be unreliable. Here’s an archive image of it in the 1980s which shows the front of the brick block before the trees matured.

Spence also designed its neighbour, the Chemistry Building (1967), to match with a horizontal building clad in the same vertical aluminium fins as the tower. But my walking loop carried on around the sports halls and then dropping down between the Sir Steve Smith Building (Hawkins Brown, 2016, formerly called the Living Systems Institute) and the next two 1960s buildings I want to mention.

Laver Building for Mathematics and Geology (Louis de Soissons, 1967)

From the sports hall, the first thing you notice about Laver is its ski-lift style roof jutting through the trees.

Predominantly brick-clad (of course) it has some concrete panels set into its side, creating a layer cake effect. I walked down the path between it and Harrison. I’ll be coming back to Harrison in a bit.

From North Park Road, Laver produces a surprise. The ‘ski lift’ block widens as it rises, and reveals huge, deep window recesses of smooth concrete. And the whole thing towers over a second, low horizontal block lifted on stilts.

Again, the form seems to suggest function: the layers along the side hinting at geological layers, and the deep recesses echoing the caves and caverns. The connection to mathematics is less obvious. It’s surprising and charming.

At this point in the walk, that westerly breeze has started to bring in the clouds.

Harrison Building (Playne Vance Partnership, 1968)

Most of the buildings on Streatham campus come in clusters that are alike. The staid 1930s work of Harris, the post war charm of Holford, Spence’s white heat of technology. Harrison is the only time the campus embraces concrete and the closest it has to a Brutalist building.

The first element that struck me was the smooth concrete balustrades, though a low one above a drop to a courtyard now has a metal safety rail. Then the building’s structure is revealed, including the concrete floors. Two strong vertical concrete blocks contain the stairwells and are clad in concrete with visible shuttering patterns. There is still a fair bit of redbrick, sandwiched between the concrete floors and the ribbon windows, but the overall impression is of a brooding brutalist building sitting alongside its more Scandinavian neighbour. Again, form reveals function: Harrison was built for the engineering department so of course it is showing how it works to the world.

This also provided me with my favourite moment of the walk. At some point, a fence of vertical wood slats was put up around part of Harrison. It’s weathered until it matches the concrete wood behind it.

If I’d turned about at this point and walked west along North Park Road, I’d have gone past Spence’s Chemistry Building and the brick Amory (Playne Vance Partnership, 1974). Instead, I cut through one of the wooded paths along a stream to get to the Forum (Wilkinson Eyre, 2012) and, very importantly the coffee van.

Great Hall (William Holford?, 1964)

Like a lot of people, I’ve been to this part of the campus for gigs or shows. The Great Hall is a mass of brick and glass, reminding me oddly of power stations whilst still hinting of the Great Halls of Oxbridge. I do think the wavy lines of the Forum, which extends tentacle-like from its main area to cut across the Hall’s main facade and up to the Northcott Theatre, rather ruin the beautiful, huge, windows. They look great in aerial shots but sat by the coffee van with rain occasionally spitting down, I feel like I expect a rollercoaster to shudder over it.

The interior remains fundamentally unchanged, with the balconies suspended from the ceiling to float above the main floor. No views obscured by columns here. The original 1960s sound baffles above the balcony are still in place. Though the asymmetrical way someone laid out the chairs made me stupidly stressed.

Hoyos-Saavedra identifies the architect as Sir Basil Spence. The ever peevish Pevsner suggests it is by Holford. I’m veering towards Pevsner here, since the marvelous, monumental northern wall has the same faint diamond pattern in its brickwork as the Northcote Building and the Old Library (both definitely Holford).

Enjoying this? You can support my work by upgrading to a paying sub for just £3 a month. That’s less than a coffee on campus.

That’s enough sitting down, onwards!

Northcott Theatre (William Holford, 1967)

Exeter lost its final Theatre Royal (unknown, 1889) in 1962, when the owners demolished it despite local businessman G V Northcott’s attempt to save it. The Vice Chancellor of the University pointed out they’d reserved space on the campus for a theatre, the city readily agreed and Northcott set up a trust to pay for it. The theatre’s 464 seats complement the 280 seats at the Victorian Barnfield (unknown, 1890s) and the 500 seat refurbished Corn Exchange (Harold Rowe, 1960).

The Northcott is currently run as a charity supported by both the uni and the city. The immediate flaw, if you are town rather than gown, is that the Northcott is a pain to get to and from unless you are already in the city centre, drive or live by the campus.

As a building, however, I think it works, mostly. Outside it is set up like blocks tumbled together, with its name boldly spelt out at the top of the brick fly tower. Inside the long, curved bar overlooks the foyer, which allows plenty of people watching and ways to wave frantically at your friends as they arrive. It feels like it owes a bit to the 1930s in terms of style. I was here for a show last autumn and the press on staircases to get into the auditorium is the one element I dislike more as the years pass.

From here, I zigzagged back to look at a couple of more buildings.

New Library (John Crowther, 1983)

This is now part of the Forum, and hard to get a good photo of the elements I like. It’s also just a tiny bit after my cutoff date but I’m going to highlight a couple of elements since it feels very 1970s rather than 1980s and it shares some similarities with Holford’s work.

Whereas most of the campus is dominated by bright red brick, the new library is darker. It has small, slit like windows in repeating rows, and makes use of the slope. The entrance at the Foyer is actually into the third floor.

My favourite element is the rows of small bays set at 90 degrees to the rest of the building, with windows in their northern sides. I know from previous visits that these used to provide excellent working nooks.

It’s been rumoured the building had to be significantly altered after it was constructed as no-one had considered the impact the weight of the books would have on its structure. That surprised me, since this is by John Crowther, a very thoughtful and thorough modernist from Truro (quoted in my deep dive into Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran). So perhaps that was a fault found with the Old Library or even Roborough? Or, as identified by Snopes, it’s actually an urban myth.

Old Library (William Holford, 1966)

The old library is probably the building I’ve visited most in the last ten years as it contains the special collections and the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum. Here’s its interior in the 1970s. We’re back to red redbrick, and Holford’s window bays clearly inspired Crowther’s 15 years later. The top panels with vertical slits echoes the addition to Northcote House (see the earlier photo with all the lensflare).

There’s a lot of building work in this area, so it’s hard to get a good photo. The entrance suggests this is not Holford’s most inspired work.

Above the wide doorway there are three recesses in the brickwork, with symmetrically laid out aluminium frame windows. Either side of the doorway are matching recesses without windows, running the whole height of the front and with Holford’s telltale faint diamond pattern. So far, so symmetrical. It echo’s the end wall of the Great Hall. And then on the right, there’s an extra recess. So the whole entrance is offset. This does not feel like the same elegant architect as the clock tower, yet it is.

After frowning at this, I looped back past the Hatherley Laboratories (E. Vincent Harris, 1952) and the farm buildings (pre-1900). I took a photo of the Lemon Grove entrance in the rather grim Cornwall House (Holford, 1971). At this point I feel like his enthusiasm for the campus has waned. Then I headed into town along the Prince of Wales Road. As at Streatham Drive, the edges of the campus hint at old lodge houses before large Victorian and Edwardian villas crowd the road.

I didn’t capture every building on the walk, but I did come away with a renewed love of Spence’s landmark Physics Building and a clearer understanding of the site. I think the old University College of the South West embraced traditionalism to gain status. Once it had the confidence of being recognised, of becoming the University of Exeter, it shook off the staid early work and embraced modernism.

Other local news of C20th buildings

I’ve been posting stories as I find them on my Bluesky. I’ll stick to one story for this week as it has a link to the University of Exeter, and will do a round-up next time.

Demolishing Truro Moorfield multi-storey car park 'sensible' | Falmouth Packet

The upper storeys were closed in May 2024, with the loss of more than 400 spaces.

The Moorfield carpark in Truro was built in the early 1970s by John Taylor, who had been partners with John Crowther (mentioned further up as the architect of the New Library at the University of Exeter). Preston bus station it ain’t, but the Truro Civic Society have written a useful summary about it.

If you know of an event or news item you think I should know about, you can contact me on Bluesky.

I’ve finished my contract work, so am planning to revert to three WCM emails a month: the deep dive, the field notes of a visit like this, and a round-up of local news that might not have been picked up outside the area.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, feel free to share it with others.

If someone has sent you this, you can subscribe below.

A free sub will get you the field notes, news round-up and notice that a deep dive has been published.

A paid sub (£3 a month) will unlock the deep dives early, plus occasional bonus content and the warm knowledge that you’re supporting the project.

In 1951, he received the RIBA Royal Gold Medal. Addressing the award ceremony audience, he said “Look, a lot of you here tonight don't like what I do and I don't like what a lot of you do ...” ↩