Civic Hall, Totnes (1960)

Exploring the history of G A Jellicoe's Civic Hall for Totnes. Includes a fire, post-punks and pilotis

It was a mizzling day in February, and the record shop was blasting out an old Cure track. I’d just spent a few hours in Totnes Archives, where a white-haired man had popped in to chat to the archivists. When I’d said I was searching for the name of an architect, he not only supplied it but told me something that unlocked a lot of the story of Totnes’ Civic Hall for me.

The main street in Totnes is narrow, steep, climbing sharply from the old wharfs on the river Dart. Elizabethan merchant houses crowd and overhang the road. Tiny, cobbled snickets lead through the houses, revealing courtyards and galleries. Totnes Archive is down such a secretive way. On Fore Street itself the entrance into the heart of the town is marked by a crenelated gateway topped with a Victorian clock tower.

Then, on the right, the market square opens out and the Civic Hall turns its blank dark slate face to the medieval fripperies.

When you live, or visit, a city that went through a blitz the patchwork of pre- and post-war buildings tells a story in stone and concrete. But Totnes, a small market town deeply nestled in the folds of Dartmoor’s soft edges, wasn’t a Luftwaffe target. So why is their civic hall from the 1960s?

Destruction

Totnes had been a rich, mercantile, town back in the days of Elizabeth I. Its wealth came from controlling the overseas trade down-river at Dartmouth. There was a pannier market where traders would bring baskets of fresh produce to sell. A shambles (meat market), a butter walk for dairy and a poultry walk for birds. I’ll be coming back to those.

As the shipping trade declined, Totnes morphed into a small but solid market town. In 1848 the town council built a Victorian market hall. It had a plain stone façade and a simple archway into the covered market area. In 1944 Totnes Borough Council debated doing something with the site.

“Mr Hendra detailed a proposal for a parking place on the present site of the pannier market… A covered market could also be erected and, if desired, could be combined with a Town Hall. He believed that when the site was opened up it would soon be developed.”

There were doubts about the traffic. (This caused much amusement at Totnes Archive when I read it out, as traffic is still A Thing.) So come 1947 a basic hall was built “in utilitarian fashion by the use of the original building and second-hand materials”. Its walls and roof were, in fact, asbestos.

“It was a wonderful market where you could buy everything from a ball of wool to live chickens.”

Then one spring day in 1955, just into the second Elizabethan era, the old market went on fire. The fire brigade jumped into action. A police constable up in the hills above the town saw the smoke and cycled down to help. Some fast-thinking person leant out of a window and caught lots of photographs, which you can see on the Totnes fire station website. The cause of the fire was never identified, though it was narrowed down to something in the boiler room.

When the excitement was over, only the asbestos walls and roof of the hall were still standing. The site had opened up. It would soon, as had predicted in 1944, be developed.

Construction

A committee was put together and chaired by RIBA member and Totnes Borough councillor Douglas Mitchell, whose relatives still hold several historic properties in trust for the town. After the fire, the old Commercial Hotel that sat on the western side of the market site had closed. Mitchell bought it in 1957, renamed it Birdwood House, and donated some of the land to the cause of building a new civic hall.

The committee appointed G.A. Jellicoe of Jellicoe, Ballantyne and Coleridge in London to draw up the plans. The Civic Hall’s commemorative booklet says that “Mr Jellicoe accepted the commission particularly in view of his affection for this historic town and the unique opportunity provided for any architect.” The cause for the affection is unknown, but two miles out at Dartington Hall, Dorothy Elmhirst was employing Percy Cane to continue the landscaping of the grounds. And Jellicoe was passionate about landscapes.

Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe (1900-1996) is, in fact, now regarded foremost for his work in landscape design: he founded both the Institute of Landscape Architects (now the Landscape Institute) and the International Federation of Landscape Architects. But he also had form designing for public authorities, including wartime housing.

In the late 1950s, Jellicoe’s partnership was also in the running for Plymouth Civic Centre (now Grade II listed thanks to a C20 campaign). And this is how the Civic Hall at Totnes reveals its story. It’s a test run for Plymouth’s Civic Centre.

Both buildings are on sites with dual slopes, and both use Le Corbusier style stilts to tackle the uneven ground. At Totnes, the key was to rotate the existing layout. The old hall had lain north to south, along the steeper slope. The new hall lay east to west. Jellicoe designed the hall to rest on two large blocks at either end of the slope, with the void beneath its bulk supported by stilts. By raising the hall to level it, there was room for shops and pannier stalls beneath on market days, and that precious parking the rest of the time.

The stilts also echo the use of pillars on the Elizabethan butter walk that is just across the High Street from the Civic Hall. The first floors of these buildings extend to cover the pavement, held up on narrow pillars of stone or wood. The walks were designed to provide shade for traders as no-one wants dairy or eggs that’s turned. Le Corbusier via Louis Pasture.

Jellicoe also took inspiration from the local buildings in other ways. The entire wall of the Civic Hall is clad in overlapping slates. Most are square, but a handful are round and are used to pick out a pattern of simple Xs across the huge face of it. Much of this pattern has been obscured as original slates have been replaced with ones that are lighter.

A slope, which to modern eyes is an accessibility feature, is original and leads to the stage door. Photos show this area originally had an open balcony covered by a porch held up by another slender pillar. At the other end of the hall, a curving concrete stair leads to a wood and glass foyer.

When you put them side by side, the way Jellicoe responded to the site’s historic surroundings is unmistakable.

A creative pattern

The hint of what is to come in Plymouth includes not just the stilts but also the decorative arts. When the Civic Hall opened in 1960, the commemorative booklet lists the artists involved.

The door handles were carved by David Weeks (1927-1996), a Royal College of Art graduate who taught at the nearby Newton Abbot art school. Weeks designed sculptural elements for Plymouth’s post war guildhall and pannier market.

A mural, Totnes in Time, by Mary Adshead (1904-1995). Adshead was one of the best-known muralists of the day. As well as murals for Lord Beaverbrook and Selfridges, she’d designed posters for the London Underground and postage stamps for the Royal Mail.

A companion mural, Totnes in Space, by Hans Tisdall (1910-1997). Tisdall had arrived in London from Germany in 1930. He found work designing book jackets for Jonathan Cape, textiles for Edinburgh Weavers as well as painting murals. He also taught, sometimes, at Dartington Hall.

And there’s Dartington Hall again.

Adshead and Tisdall would work with Jellicoe, Ballantyne and Coleridge again on the decoration of Plymouth Civic Centre in 1962. Adshead created a mural for the members’ entrance which is listed on the RIBA pix site. It’s hard not to see the Civic Hall at Totnes as a giant maquette: a small-scale version of this creative group’s plans for Plymouth.

Initial reception and alterations

When the Civic Hall opened on 20 May 1960, there were mixed reviews. The Totnes Times’ preview was damning.

“Remarks in some quarters of “white elephant”, “why build it on stilts?” and even “When be gwain to ‘ave yer first load o’ ‘ay in maister?”… There is, no doubt, a need for a tip top auditorium, whatever critics say, and to go the “whole hog”, as Totnes Borough Council have courageously done, will certainly enable first class events to be held. …[It is] not altogether an unpleasing place.”

Someone with the highly plausible name of A M Decent defended the hall in the letters page of the next issue.

“The simplicity of the building is the essence of its undoubted success, and it is most appropriate to its sitting and its intended multi-purpose usage.”

It was also still hidden: the Victorian market’s façade remains still fronted the High Street. In 1967, the façade was demolished to open up the market square to the road. This means the relationship between the Elizabethan merchant houses and the Civic Hall can be properly seen.

Then in 1969 someone dumped a giant coat of arms on the centre of the hall’s blank wall. Pedestrian retail units topped with offices and flats appeared in an annex to the eastern side, breaking the clean lines. A toilet block with cast concrete bas relief walls came from somewhere, somewhen. In 1984, three large windows were cut into the southern wall of the hall, replacing Jellicoe’s high, narrow window slits.

At some point in the 1990s, the open balcony and glass box reception by the stage door was bluntly boxed in and clad in slate.

Using the hall (sometimes)

“The hall is here for you to use.”

Mayor’s opening speech, 1960

The council member responsible for letting the hall complained, before it even opened, that local organisations and users had not been consulted, and that it was doubtful it would ever make a profit.

On the first Saturday after the opening the local Young Conservatives organised a dance. This set the hall swinging, and suggested it met one of its purposes at least: replacing the long-lost Fore Street assembly rooms as a place for young people to meet. And they did.

“I was at a dance in Totnes civic hall when news of the death of President Kennedy was announced. Went to and helped organise several dances for Redworth youth club. Some spectacular fights, one where a bloke got thrown over the rail onto the roof of a car parked below.”

Perhaps this was not the genteel artistic outreach the authorities had had in mind as by February 1964, the council cancelled some dances.

“Totnes town council decided last night to cancel “a certain block of bookings” for dances at Totnes Civic Hall because of complaints of behaviour of people after leaving the hall… Last night he reported complaints from residents in the neighbourhood of the behaviour of up to 30 or 40 young people.”

Ten years later, Totnes Borough Council was swept away by local government reforms and South Hams District Council took over. By 1976, the new council had taken a hard look at the books.

“Bad feelings came to a head when the South Hams Leisure and Recreation Committee told the town council the civic hall would have to pay for itself or face closure. Mr Shail said the old town council never expected the civic hall to pay for itself since it was financed by revenue from market stalls, shops and the car park in the market area.”

A ‘local businessman’ stepped in and leased the hall for two years. He wasn’t willing to do it again so in 1978, the town council had to raise 1p on the rates to subsidise the hall to the tune of £6,000. The local press suggested that

“The town council is anxious that the hall should be retained as a local amenity but does not want the responsibility of running it.”

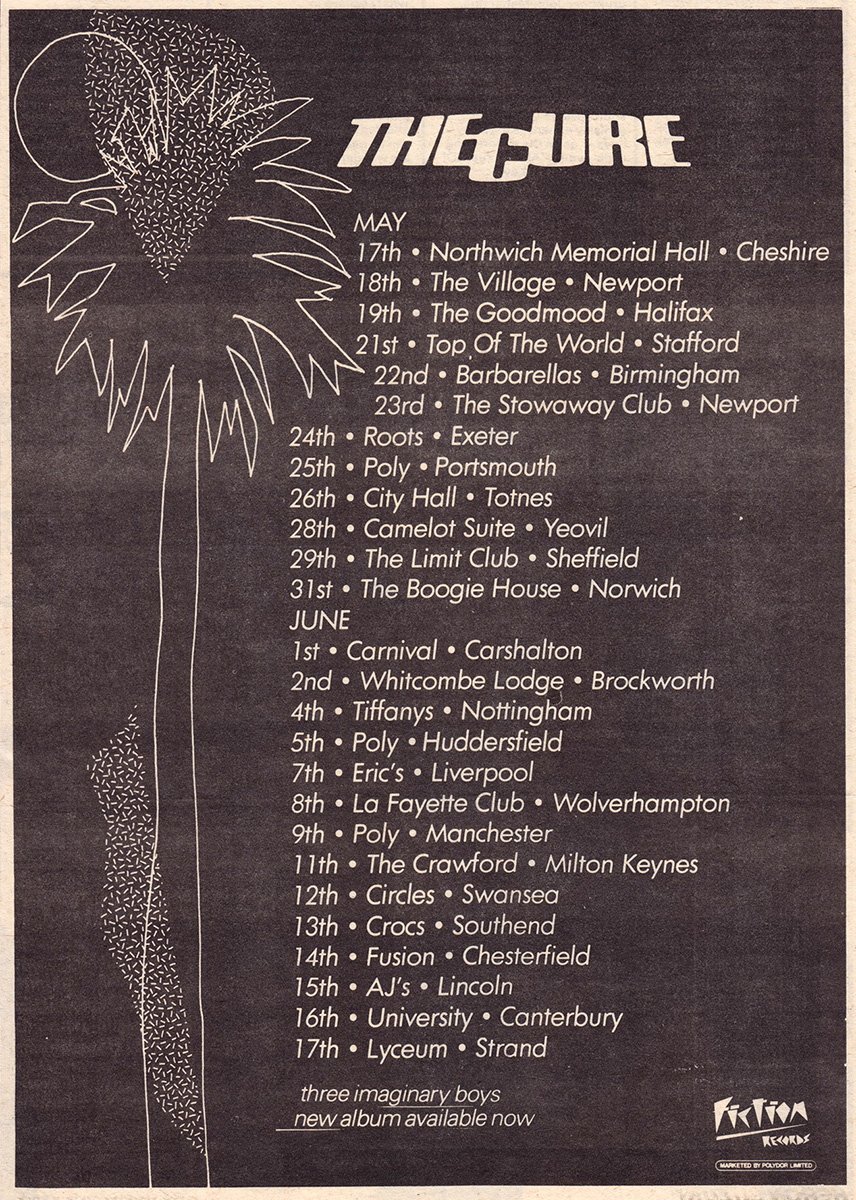

By the late 70s, live music was back. In 1977 the wonderfully named Horace Coca band and Psycho Disco Roadshow played. In 1979, the Cure and Generation X both played there.

By 1993 live music was banned, again due to complaints about noise. South Hams eventually resolved this by opening a new sports hall that could also be a live music venue. A couple of years on they were still trying to solve the white elephant they’d inherited.

“[The council] will be looking at the results of a major exhibition and consultation exercise mounted to give Totnes a chance to have its say over the future of the hall, including whether it should be flattened or merely given a major facelift.”

Future

The hall is, of course, still standing. Nips and tucks continue to be made. The main hall now has sails to act as sound baffles in an attempt to sort the acoustics. People still think it is ugly. I think a fair bit of that comes from the alterations: Jellicoe’s original design balanced the bulk of the hall with some light touches like the glass foyer and stage door balcony.

The fabric of the building itself is in decline. The rebars in the concrete stairs are visible and rusting, and ferns are growing in the cracks. The artwork by Adshead and Tisdall seem to have gone. The carved handles by Weeks are still there but are worn and cracked. A proposal to move the town council into unused annex space came in for criticism.

The town council are running it. March 2025 sees the hall host a choral concert, live music, holistic fairs, and an evening of mediumship. There’s also weekly dance and exercise classes, and the weekly market in the square on Fridays and Saturdays. In the summer months there’s an Elizabethan market, with traders and buskers in costume from the first Elizabethan era. Though it would be fun to see a new Elizabethan market with midcentury fashions and music as well.

The Civic Hall is still meeting the aims of the group who created it – providing the people of Totnes with a civic space. Even if it never breaks even.

Civic Hall details

Civic Hall, 98 High Street, Totnes, TQ9 5SN

Architect: Geoffrey Alan Jellicoe of Jellicoe, Ballantyne and Coleridge

Totnes Borough Engineer: Joseph W Smith

Builders: F J Stanbury Ltd, Plymouth

Date: 1960

Acknowledgements

Thank you, as always, to the people of Totnes who responded with memories of the Civic Hall or the market.

Also thanks to Totnes Archive which is an amazing place to spend a few hours though I can’t promise someone will appear through the door to proffer knowledge, like a damp Merlin on his way home from the shops.

Totnes Image Bank has a wealth of scanned images of the Civic Hall, and the markets. You can view their archives online.

Sources

Press clipping, 14 Feb 1944, Papers of Leonard Knight Elmhirst, Devon Archives ref DHTA/LKE/DEV/5/D

Commemorative booklet on Civic Hall opening, Papers of Leonard Knight Elmhirst, Devon Archives ref DHTA/LKE/DEV/5/D

South Hams History Forum | I'm looking into the history of Totnes Civic Hall, and am hoping members of this group can help me

I'm looking into the history of Totnes Civic Hall, and am hoping members of this group can help me! I'd like to discover people's memories of the old market hall that burnt down in 1955, as well as...

The Gallery at Birdwood House - History

The Gallery at Birdwood House

The Civic Hall is here! Totnes Times, 14 May 1960.

Letters page, Totnes Times, 21 May 1960.

https://cloudarchive.totnesimagebank.info/slideshow/?imageid=39940Opening of the new Civic Hall at Totnes, Totnes Times, 28 May 1960.

Totnes acts on dance bookings, Torbay Express and South Devon Echo, 25 February 1964.

Totnes resents ‘interference’ over Civic Hall, Torbay Express and South Devon Echo, 23 Sept 1976

Hall may be saved again, Torbay Express and South Devon Echo, 4 Oct 1978

Civic Hall future in balance, Torbay Express and South Devon Echo, 12 Sept 1996

The Buildings of England: Devon, by Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner (Yale University Press, 1991)

If you have enjoyed this deep dive into a piece of West Country Modernism, you can subscribe to get future essays in you inbox.

Paying subscribers get early access to deep dives as well as a warm Devon thank you for supporting the research time involved.