Burgh Island Hotel, Bigbury-on-Sea (1929)

The story of Burgh Island Hotel is the story of Art Deco itself. Then I started to dig, and discovered something that didn't fit.

“There was something magical about an island – the mere word suggested fantasy. You lost touch with the world – an island was a world of its own. A world, perhaps, from which you might never return.” And Then There Were None, Agatha Christie, 1939.

Burgh Island sits off the edge of the south Devon coast. At low tide, you can walk across the sandy beach to reach it. As the tide turns, the crossing vanishes. Waves overlap from both sides, with dangerous undercurrents that have taken a fair few unwary swimmers over the years. But from Bigbury-on-Sea, the mainland village, the island draws you. Or, more precisely, the hotel on it does. Glowing white render catches the light. Peppermint Crittall windows promise a world of cocktails and dancing.

In 2025, Burgh Island Hotel is the most glamourous Art Deco building in the West Country. I thought I’d have little to say about it. Built by millionaire Archie Nettlefold, fell into post-war decline, restored by Tony and Bea Porter in the 1980s. But then I started to read the contemporary local press cuttings, and realised its story is the story of Art Deco itself. Its 1930s rise as moderne, its post-war dismissal, and its postmodern restoration.

I also realised that the glamorous story of Burgh Island Hotel was not entirely what it seemed.

We’ve been to a marvelous party

In 1914, musical hall star George Chirgwin bought Burgh Island. He built a wooden “chalet style” 12 bed holiday “getaway” on it. Chirgwin died in 1922, and his widow converted his former hideaway to a hotel.1 She sold the island to Archibald ‘Archie’ Nettlefold in 1929.2

Nettlefold was born wealthy, the son of industrialists, but was more interested in the entertainment industry. As well as leasing and producing plays at the Comedy Theatre in London, he owned Nettlefold Studios in Walton-on-Thames, a sandwich and salad bar on Oxford Street and a hobby farm in Kent.3

One common story about Burgh Island Hotel is that it was originally a guest house for Archie’s friends. The 1990 Grade II listing opens with “Private guest house, now hotel. Built 1929 for Archibald Nettlefold, architect not known.”

The 1929 press coverage of its construction, however, indicates it was always intended to be a hotel.

“The purchase of the island, where he is enlarging and modernising as a hotel a house in which Chirgwin lived, is the latest enterprise of one of the most remarkable personalities connected with the London stage.”4 (my emphasis)

Construction

The architect has been confirmed as Matthew Dawson, a friend of Nettlefold’s. Dawson was Senior Lecturer at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College, London, from 1929 to 1939. He’d designed some houses for Hampstead Garden Suburb, which are distinctly in the modern British version of Art Nouveau inspired by Voysey. Tony Porter tracked down Dawson’s assistant, Jane Wailes, who recalled his work on the hotel.

“He had been appointed to design the place to ‘suit the theatrical taste of Archibald Nettlefold’. … From the beginning he faced the big problem of ‘conveyance of building materials to the island and up to the site’. As Mrs. Wailes says ‘This was solved by the decision to use the new trendy concrete, mixed on the spot.’”5

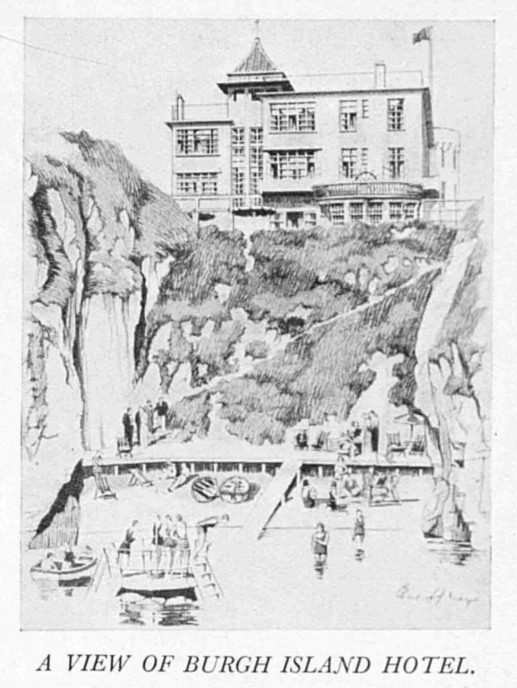

Dawson laid out the hotel in a T shape, with day rooms and balconies running along the top bar parallel to the north-eastern shoreline of the island. A ballroom, kitchen and other functional spaces were in the leg of the T. All of this was built with that most moderne of materials: reinforced concrete. Window frames and French doors onto the balconies were Crittall. Furniture was from Heals.

Yet at the southern end of the building was the entire wooden stern of the HMS Ganges, snugly attached as the hotel lounge. At the northern end was a simple round tower, complete with crenelations that ran from it along the entire front of the building. Behind that was a square, copper-topped cupola. Along with the lower ground floor portholes, it all feels like Dawson responding to the theatrical brief and the challenging site. Harriet Partridge, writing forcefully on why Burgh Island Hotel had been neglected in architectural history, says:

“Paradoxically, although Nettlefold was a ‘Modern’ man, at the forefront of the fashionable cultural scene, and despite its ‘modern’ construction and ethos, the design that he commissioned was externally not exclusively or strictly the ‘Modern’ that academics expect - the theorised, pristine, purist white box. Instead he intended to anchor the building to the ‘Treasure Island’ narrative, infused with a contemporary theatrical mood. This reveals high-end society’s awkwardness with ‘modern’ at the time: a yearning for the progressive and new, alongside the need for romanticism and escapism.”

Creating a moderne hotel

The rainhead hoppers are marked 1929, but the hotel was still under construction in February 1930, as reported locally.

“At Burgh Island, Bigbury on Sea, an hotel is being built, and the Exchange is sending there on Monday seven men to start excavation work.”6

By January 1931, Nettlefold’s manager was applying for a license to sell intoxicating liquor at the “Burgh Island Hotel”. Local coverage reveals a description of Nettlefold’s plans.

“A new hotel had been planned at a cost of £40,000. It was intended to cater for parents and children going for a holiday, and not for chance visitors. There would be 34 bedrooms, with electric lights, and the hotel would be capable of taking some 60 people. Near by a cove had been dammed to make a bathing pool, this alone costing £1,000. The hotel was first advertised in December last, and already there had been 31 applications for bookings.”7

So the story, widely repeated, that Nettlefold bought Burgh in 1927, built a weekend home, and then converted into a hotel doesn’t fit. From the start, from when he bought it in 1929, the building was always a hotel. In March 1931, the advertisements in the Tatler and Bystander magazines appear.

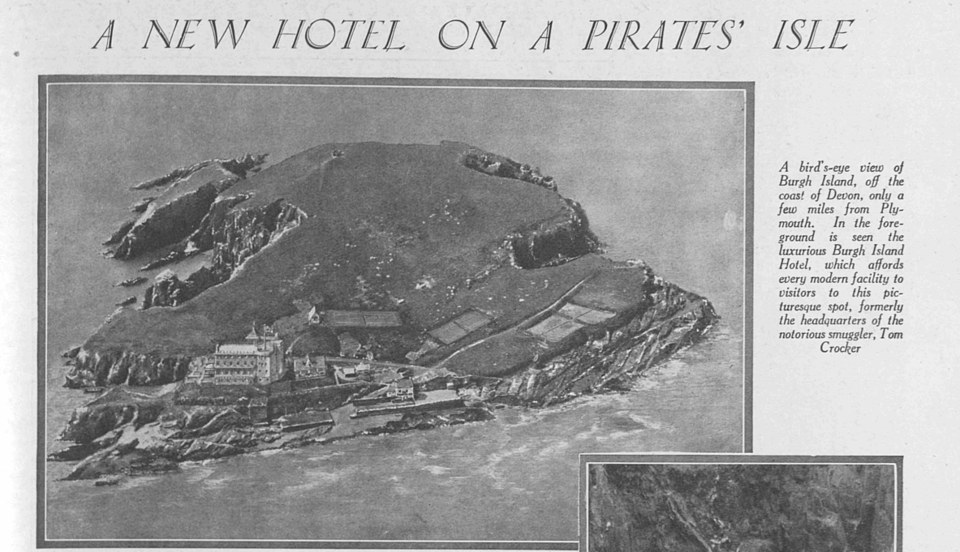

The 1931 publicity campaign makes much of the pirate connection. It also helpfully provides an early aerial view of the building.

The hotel opened for business on 23 May 1931.8

Does it matter if later histories suggest the hotel started as a house that was converted? Well, yes, when you are looking at the design of it. Why slap on a bit of a ship? Why the crenelations? It seems like an eccentric millionaire’s whim. But if your goal was to build a hotel resort for well-heeled families, the kind of place to advertise in Tatler, then the romantic ideas of a pirate island practically demand a ship’s stern for the children to play captain on, and hints of castles. The 1931 building makes more sense if it’s seen as a commercial operation from the start. The moderne use of concrete, the suggestion of the luxuries of a transatlantic liner in the stylings, all fit with drawing a wealthy set of customers.

It also changes how we think of the famous names reputed to have stayed there. Perhaps Nettlefold invited them all: Noel Coward; Agatha Christie; Coco Chanel; the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. He certainly had the connections. Perhaps they stayed (the guest books are long lost so all evidence has to come from their own archives). But Archie may have invited them to build word of mouth for his venture, not just as friends coming over to stay at his west country retreat. Having the queen of crime sat in the lounge is a hell of a selling point.

Expansion

Most descriptions of the hotel highlight the immediate upgrades made but there is some lack of clarity about when these were done and by whom. Tony Porter suggests the architect was Mr Brakespeare, of Plymouth, who did the work in 1934. He also suggests Jane Wailes designed the palm court in 1930 or so.9 Elain Harwood attributes the additional wing and function rooms to William Roseveare, also based in Plymouth, around 1930-32.10 As Roseveare and Brakespeare sound similar, I am favouring Harwood’s identification. And it’s possible the second architect used Wailes’ earlier designs.

Even as late as April 1938, marketing illustrations of the hotel have the original layout. It’s possible older artwork was used for this puff piece.

An unillustrated advert the following month talks of a new lounge, more bedrooms and a parking garage. This strongly suggests the expansion of the hotel was only finished in the last half of the 1930s and not as early as 1932 or 1934.11

Nestled into the southern crook of the T, to the left of the HMS Ganges, the palm court, with its exuberant peacock shaped glass ceiling and marble fountain, had arrived. Sitting under it feels like sitting beneath a giant’s Tiffany lamp. And if you had such a dramatic lounge, surely you’d be advertising with it?

War comes to Burgh

Yet what the hotel was advertising in spring 1938 was reduced rates: bookings were clearly down. In 1939, the British army arrived on the island and the hotel closed its doors.

In April 1941, Nettlefold moved his film studios from Walton, dangerously close to the ongoing blitzkrieg of London, to Burgh Island. According to Kinematograph, they were already shooting one film there and intended to make more films “sponsored by the Ministry of Information”.12

Just one commercial film was made on Burgh Island during WW2. Sheepdog of the Hills (1942), and you never see the hotel in it.

No further films were made as on 31 May 1942 a single high explosive bomb took out the tower and the top two floors of the original wing.

Demolition work took place in 1943 to make the building safe. William Hornby Hatchard Smith, the architect involved in the work, was taken to court in 1945 for overspending the budget the War Damage Commission had agreed with them.13

There’s the suggestion the hotel was also taken over as a military hospital during WW2, perhaps treating some of the wounded from the disastrous Exercise Tiger at nearby Slapton Sands in 1944. Certainly, there are two pillboxes ensuring the tidal causeway between the island the mainland can be raked with fire.

Nettlefold had died in 1944. His hotel, battered by a world war, went into its own fatal decline.

The smell of dead holidays

Lady Winifred Dunbar Anderson and her son, Squadron Leader Anderson, bought Burgh Island, including the Hotel, for £36,500 in 1945. Squadron Leader Anderson spoke to the local press about their plans.

“The general idea is to restore the hotel to its pre-war size. As a result of the bombing, one wing has disappeared. We hope to have it replaced and the hotel opened by next spring.”14

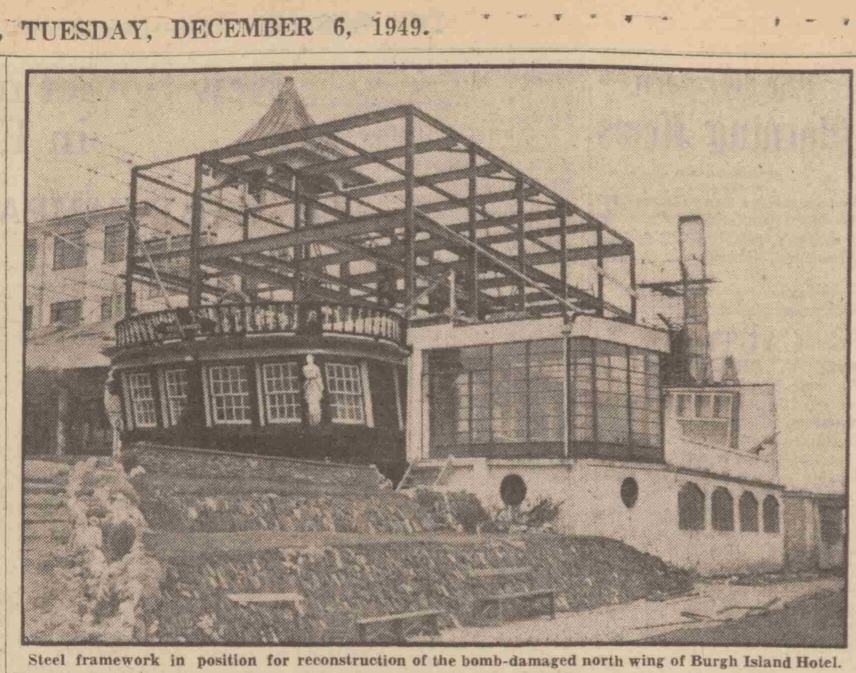

The Andersons left the running of the hotel to a general manager, Acklam, who restored its fame by blowing their budget. He also rebuilt the original 1930 wing in the winter of 1949-50 albeit without the original tower.

Five years later, and the Andersons’ were selling up. Initially up for auction, it was withdrawn from sale at £17,500 before being bought through a private sale in 1955,15 apparently to someone called Crowley.16 Within a year, a small classified ad was appearing: you could now stay on Burgh Island in luxury “flatlets”.17

Clearly not that luxury. A scathing write up by Michael Irving in The Sunday People in June 1962 describes a near empty hotel, where the “children’s play area” is just an empty room with a blackboard.18 It was sold a month later to Arnold Hagenbach, chair of the Arndale Property Trust, for £110,000.19 And again, in 1964, when the asking price of £220,000 also included the Bigbury-on-Sea development on the mainland.20 It feels like that sale inspired the plot of John Boorman’s Dave Clark Five film Catch Us If You Can which was shot in early 1965. Burgh Island Hotel appears at 1hr 22m, and is in a wretched state.

“It’s completely deserted - it smells of dead holidays”. (Dinah)

A decade later, in 1976, the island and hotel were owned by Tom and Susan Waugh, who were claiming Christie wrote Evil Under the Sun in a gazebo on the island. That was part of their pitch to the makers of the Ustinov adaptation to film at the hotel. They declined.21

It's unclear when the Waughs sold up but in 1981, Burgh was sold to Landstone Estates Ltd. The departing owners threw anything the new owners didn’t want, such as old Lloyd Loom chairs, off one of the cliffs and burnt it. Landstone got permission to turn the hotel into timeshare apartments.22

“Already workmen have moved in to rip out parts of the old hotel interior to make room for 25 two and three bedroom holiday units.”23

The old Deco hotel, like its contemporary liners, was being broken up. Its contents had literally gone up in smoke, and the Crittall French doors were being ripped out.

Revival

The restoration and revival of Burgh Island Hotel is down to two people: Bea and Tony Porter bought the island and most of its buildings in January 1986. In the mid-1960s, 1930s decorative moderne had been renamed Art Deco. By the 1980s, after the demolition of the Firestone Factory and the founding of the Thirties Society (now the C20 Society), Deco was starting to be recognised as worth saving. The Porters could barely afford the island, much less the remaining contents of the hotel. They watched smoke billowing again from the cove where the outgoing owners burnt anything moveable that hadn’t been sold.

For the Porter’s first season, the hotel was still self-catering. They focused on restoring the palm court first, and their initial efforts can be seen in the 1987 BBC Miss Marple two-parter Nemesis.

In 1990 the hotel was among the first Deco buildings to be listed. And finally, in 2001, ITV’s Poirot filmed a feature-length adaptation Evil Under the Sun in the hotel that had inspired it. (Currently watchable on ITV Player, mes amis.)

The Porters sold to the Orchards in 2001.24 In 2018, the Orchards sold it to Giles Fuchs. He put it on the market in 2023 for £15 million, only to withdraw it from sale late last year. Every owner since 1985 has worked passionately to make the Hotel more sumptuous, more glamourous, more Deco. It’s almost impossible to imagine it was once so dilapidated that Tony Porter only got the Ballroom warm enough for the opening night party by holding an oily rag over a leaking pipe in the boiler room.

Escaping to the past

I’ve had an afternoon tea at Burgh Island Hotel since Fuchs bought it. I’ve never had such perfect cucumber finger sandwiches, or scones so fresh they warm the napkins they are served in. Naturally, we had dressed for the occasion: I wore a modern replica of a 1940s tea dress. We sat in the sun of the palm court with the fountain tinkling. I lost touch with the world for a few hours.

In 1988 Gilbert Adair wrote about how the increasingly popular post-modernism flirted with the imagery of the 1930s. He described it as “a stylized and brilliantined version of itself”. The article included a photo of the restored palm court at Burgh.25

Reading that, I thought about how, when people play at the past, they always play at being the haves rather than the have-nots. Anyone coming to Burgh Island comes to be in Brief Lives or Evil Under the Sun, Coward or Christie. No one plays at being in service, or raises Coco Chanel’s Nazi connections. As with Nettlefold’s original building, the current Burgh Island Hotel offers a romantic escapism. A nostalgia for a fictional past.

Christie saw beneath the beautiful surface attraction of escaping to an island. Burgh Island Hotel today is an artifice, a shiny, glamourous film set that pretends the building wasn’t blown-up, stripped down or gutted. That it wasn’t originally a hotel but a millionaire’s private pleasure palace.

That fantasy in itself, is true to the origins of the building: Nettlefold was building a dream to sell to people. Restoring the commercial decisions behind the escapist design helps draw out the parallels between the hotel and Art Deco’s rise, fall and revival.

Burgh Island Hotel details

Burgh Island Hotel, Bigbury-on-Sea, TQ7 4BG

Architect: Matthew Dawson (1929), William Roseveare (1938?)

Builders: unknown

Date: 1929-1930, extended 1938?.

Acknowledgements

I’ve worked my way through the British Newspaper Archive to find contemporary secondary sources on the dates of building and sale. I’ve used footnotes to cite sources for this, since I’m aware I’m suggesting a revision to the history of the building. It is possible there are primary sources not available to me that confirm the extension to the hotel was in 1932 or 1934 and not as late as I suggest. If you have primary sources, or more information that changes my theory, please get in touch.

This deep dive would have been impossible without Tony Porter’s 2002 memoir. As well as detailing the Porter’s restoration of the hotel, it has reminiscences from former guests and people involved in the original construction.

Thank you to the media team at Burgh Island Hotel for sharing some high res images of the hotel as it is now. I really do recommend the afternoon tea there.

Sources

The Great White Palace, by Tony Porter (Deerhill Books, 2002)

Art Deco Britain: Buildings of the Interwar Years, by Elain Harwood (Batsford, 2019)

Burgh Island Hotel: plenty to know, Architects’ Journal, by Harriet Partridge (November 2013)

The Buildings of England: Devon, by Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner (Yale University Press, 1991)

Footnotes

Notices: hotels, Western Morning News, 27 April 1923.

The White-Eyed Kaffir’s Island, Liverpool Echo, 18 Apr 1929.

He’s Bought An Island Now, Sunday Despatch, 29 Sept 1929.

ibid.

Porter, Great White Palace, page 110-111.

Unemployment in the West, Western Morning News, 8 Feb 1930.

£30,000 hotel on Burgh Island, Western Morning News, 3 Feb 1931.

In Smugglers’ Lair, Daily Herald, 25 May 1931.

Porter, Great White Palace, page 110-115.

Harwood, Art Deco Britain, page 146.

I have a theory 1934 is often cited as Evil Under the Sun describes the Jolly Roger hotel as gaining a cocktail lounge that year. But Christie wrote Evil Under the Sun in 1941 and many details of its hotel are different to Burgh Island even if the island layout is the same. In And Then There Were None (1939) the private island has a moderne house on it, built by a millionaire. It’s important to remember Christie routinely fictionalised bits of Devon: neither of her two islands inspired by Burgh are historically meaningful.

Nettlefold Transfers to Devon, Kinematograph, 10 Apr 1941.

Repairs to Hotel, Western Morning News, 25 Jan 1945.

Resort is planned, Western Morning News, 15 Nov 1945.

Island sold, Bradford Observer, 25 May 1955.

Porter, Great White Palace, page 122.

Holiday accommodation, The Evening News, 2 May 1956.

I Got a Shock on Paradise Island, The People On Sunday, 17 Jun 1962.

£160,000 ‘Pleasure Island’ near Plymouth, Coventry Evening Telegraph, 11 Jul 1962.

An Island of Your Own? The Evening News and Star, 26 Oct 1964.

Agatha Christie’s industry goes on, Hull Daily Mail, 13 Jan 1976.

Porter, Great White Palace, page 71 and 124.

£1m plan for stars’ island, Torbay Herald Express, 3 Nov 1982.

Porter, Great White Palace, page 289.

The Age of Parody, Illustrated London News, Nov 1988.