Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran, Cornwall (1973)

How do you balance tradition and modernity? One Cornish Brutalist church is the story of those contradictions, and how one woman spent her life balancing them.

"Every tradition was once an innovation and every antique a red-hot artefact.”

There was an old lady devoted to goats. She lived in one room of the small, terraced cottages that line Richmond Hill, the steep route from Truro city centre to the railway station. She dressed in headscarves and embroidered diurnal skirts “like a Russian peasant”, and wore work boots, or went barefoot.

Every town had such a woman. Where I grew up, ours, Bertha, had a large collection of rescued and stray dogs who she took around town in an old-fashioned pram. She was bloody-minded, of course. Truro’s own bloody-minded woman, Peggy Pollard (1904 to 1996), left more than just memories. She made sure swatches of the Cornish coast were not built on and holds the Guinness World Record for the longest single piece of embroidery. She was also responsible for building a modernist, Brutalist, Roman Catholic church.

For this deep dive, I’m taking a look at the church Peggy Pollard made happen: Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran in Truro. It’s a story that starts a long way from a decrepit cottage in Cornwall. It starts with a bored rich girl born in WC1.

Nowadays, we think of Methodism as the predominant version of Christianity in Cornwall. When John Wesley arrived to preach in the open air in the 1740s, he found a receptive audience. A wander around any part of the county now will find granite Wesleyan chapels set foursquare to the elements. But before that, Cornwall had been a Catholic stronghold. There are a lot of Cornish saints. A lot. Such as St Piran, whose oratory at Perranporth (circa 600s) is wrapped in concrete to protect it from the sand that would bury it.

The introduction of the first Book of the Common Prayer in the 1540s, and the insistence that services be in English, did not go down well in Cornwall. In the more westerly reaches English was not yet the main everyday language.

“we the Cornyshe men (whereof certen of us understande no Englysh) utterly refuse thys newe Englysh.”1

After the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549 ended with thousands killed, the Cornish identity was more firmly repressed. Between the aftermath of the rebellion and the arrival of John Wesley, the Cornish language was almost wiped out. It survived in fragments: a counting song here, a shout to launch boats (Hunchi boree!) there. Then the late Victorian Celtic Revival crossed the Tamar. By the start of the twentieth century, a new Cornish was being built from the relics of the old language.

We will be getting to the architecture, I promise. Sometimes the story of a building needs telling through telling the story of a culture and a person, and this is such a story.

Margaret ‘Peggy’ Pollard

In 1904, the same year that Henry Jenner published his first handbook of Cornish words, Margaret Steuart Gladstone was born at 2 Whitehall Court, London. The building is now part of the Royal Horseguards Hotel. Her family, relatives of the Gladstone, had 22 servants on hand in their lavish home. The family moved to Surrey, where Peggy taught herself Sanskrit from her father’s books. After his death, she went up to Newnham College, Cambridge. Peggy, as she was known, later said “I lived what would now be called the Life of Riley.”

She was part of a set of young women who wore trousers, cropped their hair and generally caused scandal. She had girlfriends. She had boyfriends who also had boyfriends. She became the first woman to gain a double-first in Oriental languages. She and some of her friend group were very taken by Clough Williams-Evans’ book England and the Octopus (1929) which decried the urbanisation of rural England. Peggy and friends turned their existing joke name for themselves, Ferguson’s Gang, into a fund-raising and publicity stunt group for the nascent National Trust. Peggy, under the name Bill Stickers, was their leader. You can read the full story of their adventures in Polly Bagnall and Sally Beck’s Ferguson's Gang: The Remarkable Story of the National Trust Gangsters (National Trust & Pavilion Books, 2015).

In 1931, Peggy married Captain Pollard, a university boyfriend. They settled in St Mawes, Cornwall, just beside Our Lady Star of the Sea and St Anthony. Peggy realised her husband’s first love was, in fact, the sea. Idle, independent and with a talent for languages, she threw herself into learning the newly revived Cornish. She published Cornish poetry and was made a Bard in the Gorsedh Kernow by 1938. She took the Bardic name Arlodhes Ywerdhon (the Irish Lady), after the rocks near Sennen Cove which was a coastline Ferguson’s Gang had helped the NT buy.

In 1936 a Catholic Mass was first said in Our Lady Star of the Sea and St Anthony. Peggy herself converted to Catholicism by 1951, apparently after reading CS Lewis’s Screwtape Letters.(Church Times) At some point, the Pollards moved to an Edwardian house in Pydar Street in Truro and Peggy joined Truro’s St Piran RC congregation.

The Guild of Our Lady of the Portal

The earliest records of a Guild of Our Lady of the Portal in Truro are from the 1420s, a century before that Prayer Book Rebellion. Kresen Kernow holds a typewritten sheet of the history by an unknown author (a bit of me dreams it was by Peggy herself).(AD1600/1/29) It catalogues mentions of the Guild, and how locals would donate moneys to it in return for the Guild maintaining a bridge near the entrance to Truro. By the 1950s, the bridge and the guild was long gone though a booklet by H M Gillett suggests it had been on St Clement’s Street. Truro’s Catholic community was meeting in the small church of St Piran’s (Silvanus Trevail, 1884) on Dereham Terrace. It was this overflowing congregation Peggy Pollard had joined. By Lady Day in 1963, they had built a new Lady shrine on the site, complete with a small Basque Madonna and child statue set on a granite block.(AD1600/1/29)

In the 1960s Peggy reestablished the Guild as a remote congregation. Members of the Guild were given numbers and would say the rosaries together in pairs over the phone.

“At a given hour practically all the lines to West Cornwall would be jammed by Hail Marys.”

(Times obituary, part of X1104/4/582).

And so, at last, we reach the design and construction of the new Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran church. The congregation needed a bigger place to meet, and Peggy set about making it happen.

“I was married in 1971 to my first husband in that little Catholic Church and couldn’t even walk down the aisle properly with my new husband because it was too narrow.” (Facebook user, 2014)

Design and construction

No sooner had I read that Vatican II (a 1960s conclave that sought to modernise the RC church) caused the surge in modernist Catholic churches than I read multiple articles debunking this. The Vatican II theory also ignores that other denominations also moved towards modernist churches during the twentieth century, such as Exeter’s Mint Methodist Church and the now deconsecrated CoE St Andrews. In the Historic England guidance note on 19th and 20th century Roman Catholic churches, Andrew Derrick suggest that one of the major prompts for the embrace of modernism was the design for Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral (Frederick Gibberd, 1967).

An undated leaflet seeking funds for a new church, called Our Lady’s Shrine Restored, describes the plans for church for perhaps 250 people and a meeting room that could cope with 100 people. “The architect’s idea,” it says, “is to achieve a sense of peace and tranquility.” (AD1604/14/8)

So, who was the architect?

MWT Architects

The commemorative booklet says

“More ground was acquired and the plans for a new church to be dedicated to Our Lady of the Portal (an ancient devotion in Truro) and St Piran were drawn up by Mssrs Marshman, Warren and Taylor.” (AD1600/1/29)

Marshman, Warren and Taylor, also known as MWT Architects, were responsible for a lot of modernist public buildings around the West Country. Sadly, the MWT collection held at Kresen Kernow hasn’t been fully catalogued yet so I can’t confirm with certainty which architect was responsible for Our Lady of the Portal. However, there are some plausible clues that suggest this may be the work of senior partner John Taylor.

John Taylor (unknown dates) started his career in the County Architect’s office in Portsmouth, before doing three years of National Service in the Army. After qualifying as an architect in Edinburgh, he joined the Cornwall County Council’s architect’s office where one of his colleagues, J H Crowther, introduced him to his son, John Crowther. The two Johns, Taylor and Crowther, started their private practice in 1952 based on the AJ write-up of them in 1954. “Both partners,” the write up says, “are uncompromisingly modern in their designing.” (AJ 1954)

As Taylor and Crowther they built Martin’s Bank (1958) on Boscastle Street, Truro, and a number of private properties. (AJ, 1958 and 1959). Recalling their time together, John Crowther would say John Taylor was “A brilliant architect in many, many ways”. (Crowther Remembered)

At some point after 1963 Taylor and Crowther seperated. Taylor joined forces with Arthur Marshman, and someone called Warren. English Heritage, when listing Marshman’s home Horton Rounds in Northampton, describe MWT as

“a substantial regional practice specialising in commercial buildings who built extensively outside London. They are best known for their work in Devon and Cornwall, which included the Chapter House at Truro Cathedral (1974) as well as large offices and housing association schemes.” (Horton Rounds)

Truro Cathedral’s Chapter House (1967) is credited to John Taylor by Pevsner, as is the Redannick estate of the 1960s. Right next to the site of Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran is the Pentecostal Church (1973). The Truro Local Plan credits this building to John Taylor with Roger Deeming, both of MWT.(Truro Local Plan) Combined, these all suggest that John Taylor was well versed in building sacred spaces. Then of course, there is the design.

The fund-raising leaflet describes the plans for the church.

“The church will be in the true Cornish idiom - a white rectangular building boldly overhanging a plinth of Cornish granite and have in it a gateway or ‘Portal’ over a flight of steps.” (AD1604/14/8)

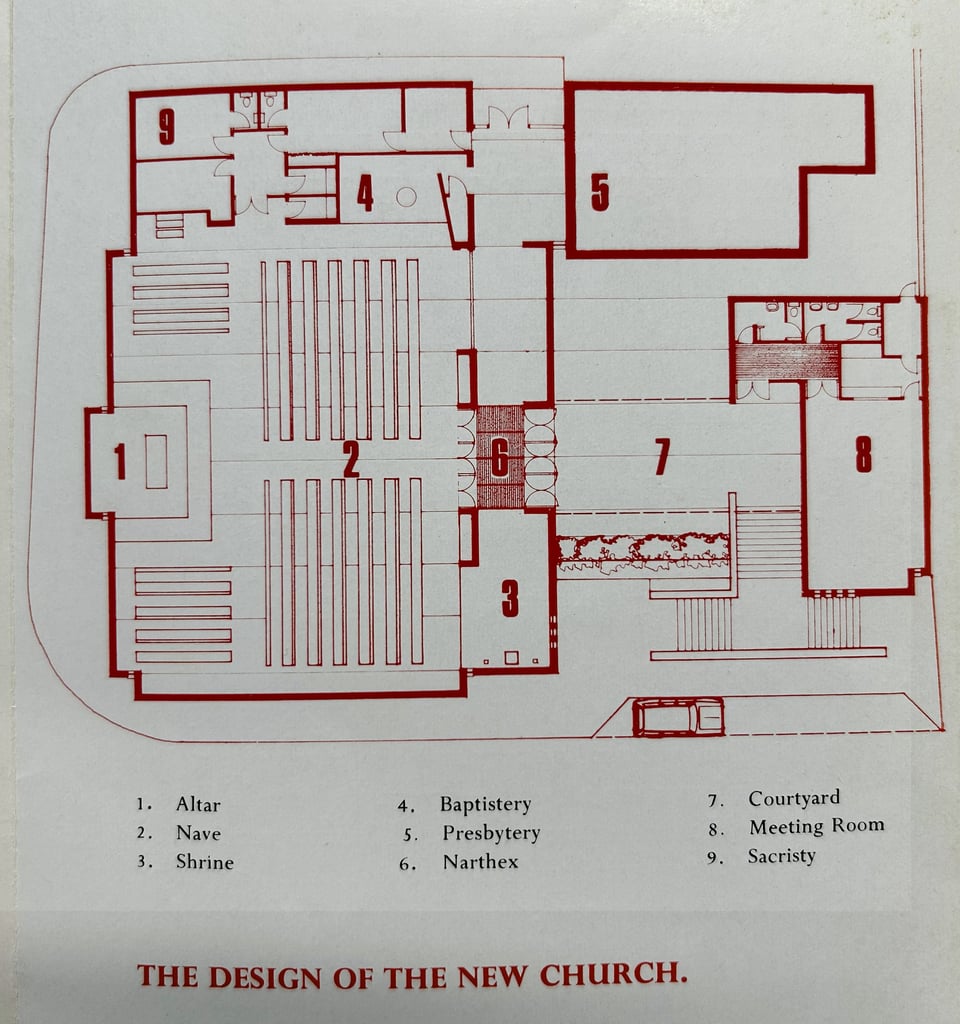

The church sits at the eastern end of the site, with the meeting room opposite and the presbytery to the south. The use of the plinth enables the whole group to be level, hiding the slope. The main entrance is through the portal, climbing stairs and through a gate, but the slope does mean there is also level access through the southern doors into the narthex.

It is “uncompromisingly modern”.

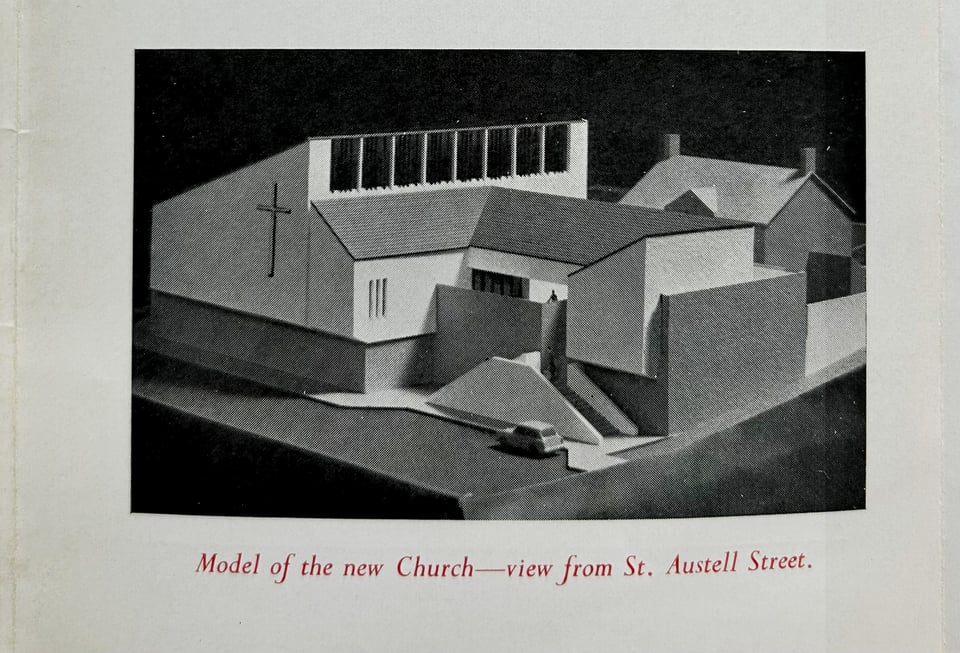

Looking at the model, compared to the current building, and there are some differences. The ‘portal’ through into the courtyard is now on the same line as the plinth, with a single set of steps within it rather than an external staircase. And the now looks more like interlocked blocks than in the original.

There’s also no covered walkway between the narthex and the meeting room. There’s no evidence on the ground that these were built and then removed.

Exploring the site, the most striking element from the outside is the huge, monopitch roof of the “white rectangular building”. The higher, western side, has a single wall of clerestory glass running the entire width of the building.

This dramatic roof is similar in style to the monopitch roofs of Taylor’s work at both Redannick and at the Pentecostal church. I would suggest that, from within MWT, we are almost definitely looking at John Taylor’s work here.

Construction

Work on the church started in January 1972 with George E Wallis and Son as the builders.

“The site of the new church is in St Austell St quite near where the original church of Our Lady of the Portal would have been.”

During construction, they found a spring-fed well on the site. This now sits under a slate slab set into the floor and reading Fons Mariae matris pastoris et agni (the Well of Mary, mother of the Shepard and the Lamb).

There is very little press coverage about the construction. Though the British Newspaper Archive is limited to the weekly West Briton during the early 1970s and more may have been carried in the daily, the Western Morning News. This means most of the information comes from the commemorative service booklet.

From the outside, the building is all about the huge mass of the blank walls over the plinth. From across the street, it’s possible to see the huge plain glass western wall but no other windows are obvious. For me, the moment where the use of uncompromising modernism really reveals itself is if you go inside.

Firstly up the ‘portal’ steps and into a quiet courtyard, instantly reducing the sound of traffic. Then into the narthrex. Here the wrought iron gates of the Lady Chapel, by Davey and Jordan of Penryn, are locked.

The glass doors into the main church are set into a glass wall. Inside, the wood-clad ceiling, perhaps 30 feet above you at the doorway, drops dramatically to the eastern end and focuses your attention on the altar. And the eastern end of the interior is lit by both the huge plain western windows behind you and the beautiful tones of the dalle-de-verre that is hidden in sidelights either side of the altar.

Dom Charles Norris

These four pieces of dalle-de-verre (literally ‘glass slab’) are by Dom Charles Norris (1909 to 2004) of Buckfast Abbey. Norris had studied at the Royal College of Art in the 1920s before joining the Benedictine order at Buckfast, where he worked on rebuilding the abbey. Many of the RC churches Norris designed windows for are listed. His work at Buckfast is extraordinary.

There’s a chapter on his work by Robert Proctor in Buckfast Abbey: History, Art and Architecture (ed. Peter Beacham).

The four lights that surround the altar at Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran are in beautiful yellows, shading to orange and red. Even with the light from the huge westerly window, the altar area glows.

What I particularly like, however, is how he used colour. The altar is bathed in warmth, amber and honey and gold. Entering the Lady Chapel, and his final, single dalle-de-verre window is revealed in its whites, blues, golds and purples. It bathes the small statue of Mary in her colours. Norris also created to two banners of the Catholic Women’s League that hang in the chapel.

The total cost of building the new church, including furnishings, was £70,000.

Early use

“Our children were christened there one 1973 and the other 1975. We were married at the old Catholic church in Chapel Hill.” (Facebook user, 2025)

The church was opened on 17 May 1973, with hundreds attending a solemn blessing and first Holy Mass conducted by the Bishop of Plymouth, the Right Reverand Cyril Restieaux. (West Briton).

At the consecration, Margaret ‘Peggy’ Pollard was the organist, using the new George Osmond pipe organ that remains in use today. After the service, she let a young boy who was learning to play, Michael Maine, try it. They struck up a friendship, and he would visit her on Richmond Hill.

"I thought it was all amazing. There are people who transform lives, and she transformed mine and enlarged my vision, for which I am ever grateful. She had spent 20 years playing patience, she told me, and said I had fired her to do things." (Church Times)

They must have talked about C S Lewis, with whom Pollard had a correspondence. Maine mentioned his love of the Narnia books and suggested she could embroider them. She took up the challenge, eventually making a single piece 937 meters long, covering the entire chronicles. She remains the Guinness World Record holder for the longest embroidery.

The parish priest at both the old and new churches was Father Maggs. As well as all the services in the church, the hall was – and is - used for every kind of community event. There are notes about music evenings and packing shoeboxes at Christmas. And, of course, there was a youth club.

“I went to thunderbirds club there which was kinda a cross between scouts/guides and a youth club.” (Facebook user, 2025)

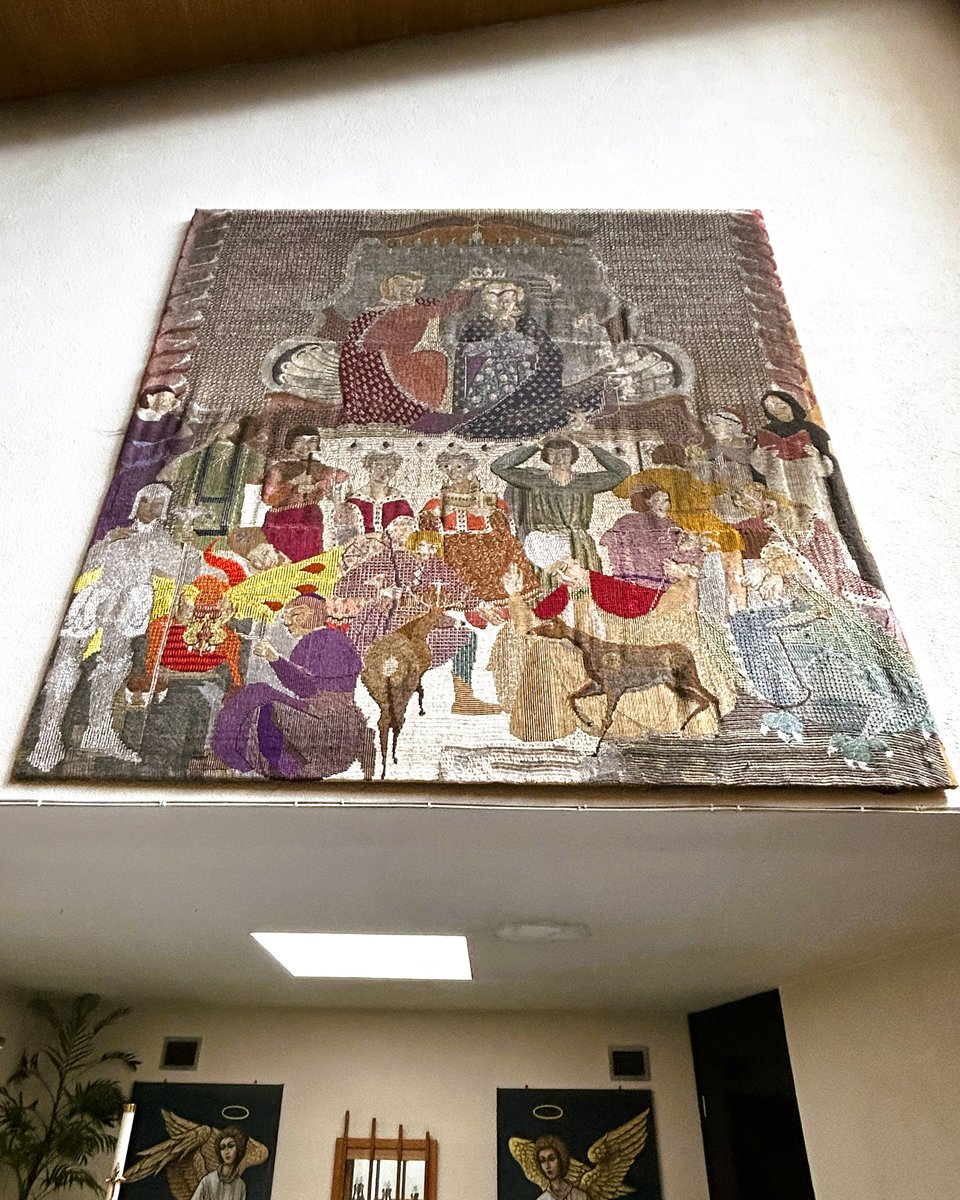

To the right of the altar, on the southern side of the church, there is a Baptistry. The marble font was transported from the old church to the new. Above it is a large modern tapestry of the Coronation of Our Lady surrounded by the Fourteen Holy Helpers.

This is a copy of another work from Vierzehnheiligen in Bavaria, and it was made by Margaret Pollard. The church’s current leaflet describes her as “a former parishioner…who did so much to support the church in its early days and raised the money for its building.”

When I first read that note, I imagined a woman, probably old, who rattled collecting tins on a high street. Then I read something else, and it made me look for her story and discover a woman who had been far, far more than that. For her work enabling the church to be built, Pollard received the Benemerenti Medal from the Pope to honour her services to the Catholic Church. Her work as the founder of Ferguson’s Gang was only revealed after her death: she had arranged a letter outing herself as Bill Stickers to be sent to the Times.

Current

I visited Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran in June 2025. The buildings and the interior of the church seem significantly untouched since 1973. Not quite a time capsule, but almost.

The altar is made of reconstituted stone from St Austell, and its simplicity – two uprights holding up a horizontal - reminded me of forms such as Lanyon Quiot near Morvah. That in turn always makes me think of the stone table on which Aslan was killed in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Above the altar at Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran is a crucifix which shows a living resurrected Christ on the cross rather than his suffering. This is figurative, but heavily stylized, and feels very of the 1960s or 1970s. Even the tiles of the narthex and the ‘pull’ signs on the doors look original.

In 1993, the church sought planning permission for some changes to the front entrance of the church site. (C1/PA03/0214/93) The documents to accompany this have not been scanned or loaded into the planning portal so it’s hard to be sure. The church itself is still configured as it was in the plan but the entrance to the hall is different.

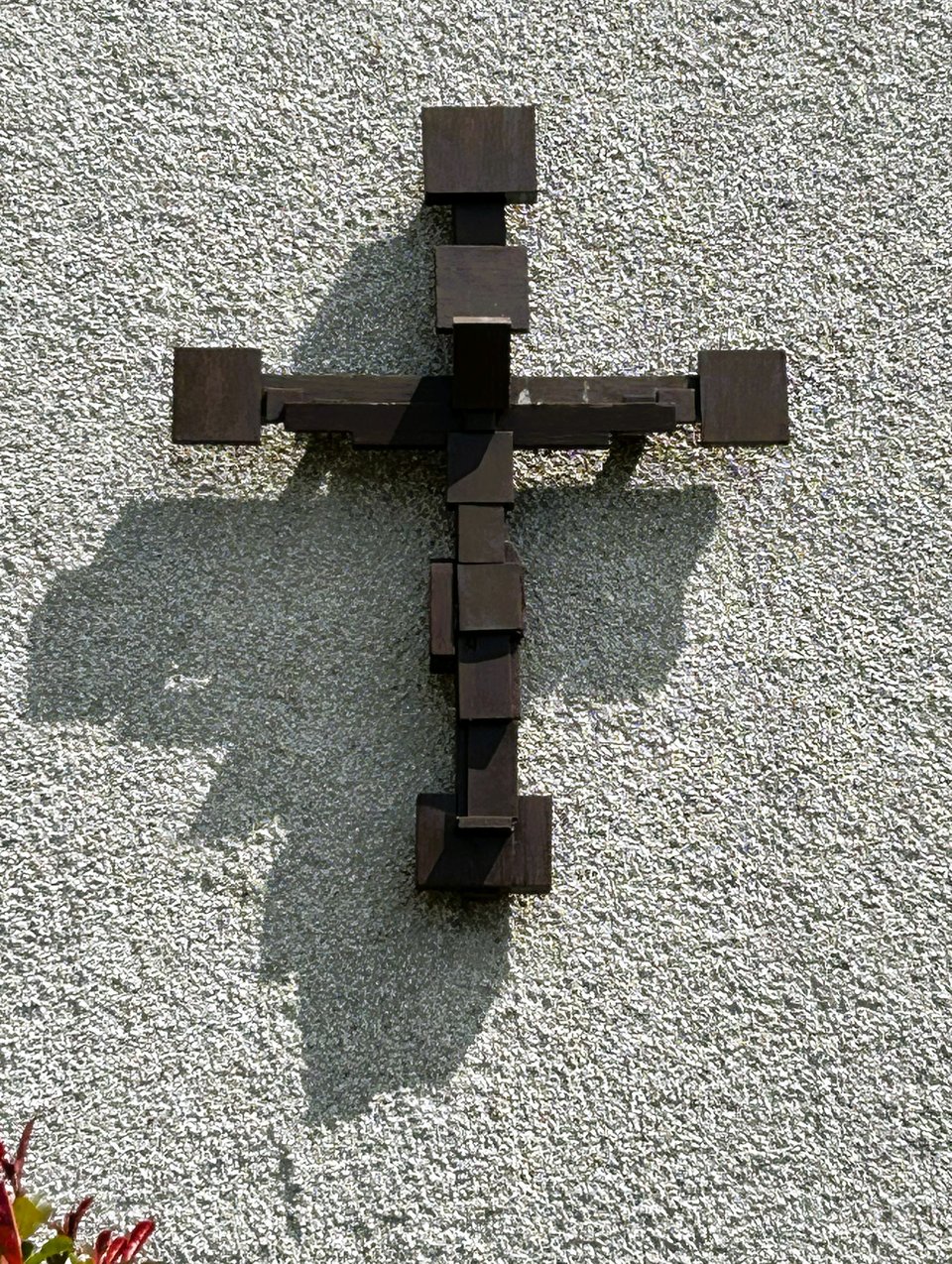

In the courtyard outside, there is an abstracted wooden crucifix designed in 1996 by Michael Finn (1921 to 2002). Finn had trained at the Royal College of Art. He was the Principal of Falmouth School of Art from 1958 to 1972, where he had been friends with Barbara Hepworth, Patrick Heron, Bernard Leach and others of the St Ives colony. After a period as Principal at Bath Academy, he retired to Tregeseal near St Just and devoted himself to abstract religious work. Sister Wendy Becket, writing about his work, considered him a modern master. The crucifix in Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran is one of two to his design in Truro: the other is in the Cathedral.

One of the curious contradictions of this building is that it exists both as a continuation of ancient traditions, yet with a firmly, uncompromising modernity to its design and construction. That reflects the contradictions in the woman who did a lot to make it happen. In their biography of her gang, Bagnell and Beck wrote

“In 1973, she built a modern Catholic Church in Truro called Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran. Its contemporary design is a surprise considering her passion for saving old buildings, but then, Peggy was never against progress, just the destruction of the past.”

Back in 1947, Peggy Pollard wrote a book about Cornwall. She said "Every tradition was once an innovation and every antique a red-hot artefact.” She used technology to connect remote members of her faith across western Cornwall, saying rosaries together on the phone every week. In a move I’m sure she would have appreciated, in 2020 the church livestreamed mass during the pandemic.

When I started researching this building, I thought I’d been looking for an architect. Instead I found “an old woman who loved goats” and who dedicated her life to building a church.

Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran details

The Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran, St Austell St, Truro, TR1 1SE

Architect(s): Marshman, Warren and Taylor (MWT) - probably John Taylor

Builders: George E Wallis and Sons

Date: 1973

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the secretary of Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran for showing me around, and for sharing my request for memories in the parish bulletin. Also thank you to the parishioners who responded to my request on Facebook.

Kresen Kernow provided access to some of the original documents and some suggestions on further reading. They host monthly Cornish lessons if you want to make like Peggy Pollard and learn Kernewek.

Sources

Derrick, Andrew. 19th- and 20th-Century

Roman Catholic Churches Introductions to Heritage Assets Historic England (2017)

Pevsner, Nikolaus and Beacham, Peter. The Buildings of England: Cornwall (Yale University Press, 2014)

Bagnall, Polly and Beck, Sally. Ferguson's Gang: The Remarkable Story of the National Trust Gangsters (National Trust & Pavilion Books, 2015).

AD1604/14/8 Our Lady’s Shrine Restored, Kresen Kernow.

AD1600/1/29 Solemn Blessing and first Holy Mass of the Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran (and related papers). Kresen Kernow.

X1104/4/582 Gorsed Kernow Margaret Pollard biographic file, Kresen Kernow. Includes Times obituary.

Cornish Historic Environmental Record entry for Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran.

Truro Local Plan, especially for Malpas area.

Taylor and Crowther, Architects’ Journal, 27 May 1954.

Bank in Boscowen Street, Architects’ Journal, 30 Oct 1958.

Four Houses in Truro, Architect’s Journal, 12 Feb 1959.

RC Bishop in £70,000 church ceremonial, West Briton, 24 May 1973.

John Crowther Remembered, Truro Civic Society, 17 Sep 2012

Howse, Christopher. Sacred Mysteries: Pictures made with slabs of coloured light, The Daily Telegraph, 28 Oct 2017

Ashworth, Pat. The Lion, the stitch…, Church Times, 15 May 2015

Trevenen Jenkin, Ann. Obituary: Margaret Pollard, The Independent. 07 Dec 1996

Well known for Embroidery and tapestry work, West Briton. 21 Nov 1996.

Endnotes

The Demands of the Western Rebels, 1549 cited in Anthony Fletcher and Diarmaid MacCulloch, Tudor Rebellions (Pearson Longman, 2004)