The Flesh is Everything

Hi Frogs, Ry here. This month I’m running an essay I’ve been working on about one of my favorite hidden gems from the pre-Vertigo days at DC. I originally conceived of this issue as being an exploration of many different books from that time period in celebration of the impending return of the imprint. But, well things got away from me. I still have many of those books featured in the ‘notvertigo’ collection on my shop and if you use the discount code NOTVERTIGO you’ll get ten percent off those items at checkout. Without further ado:

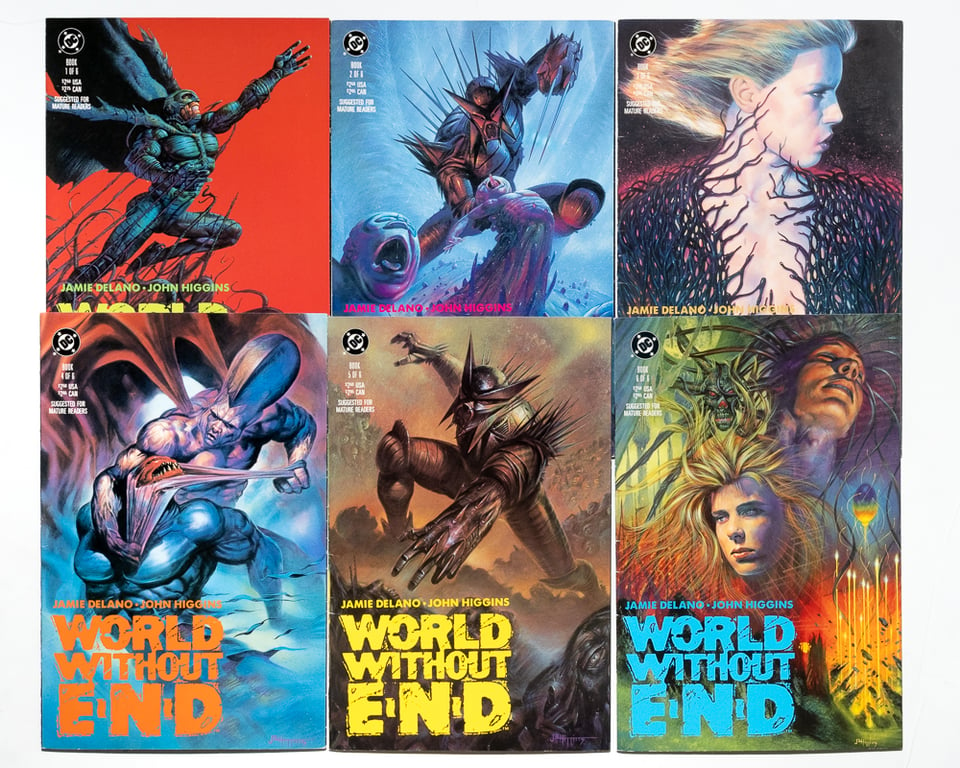

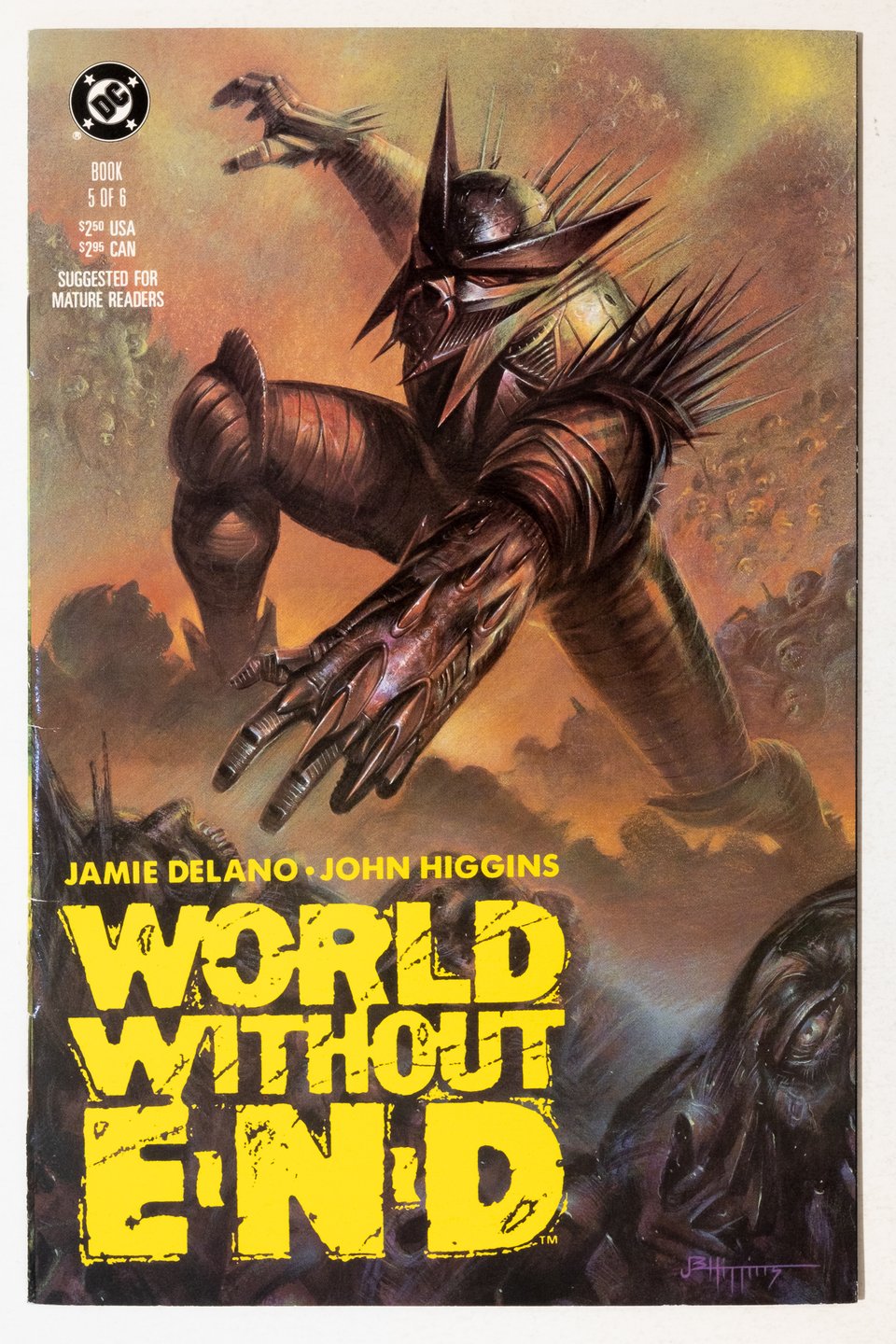

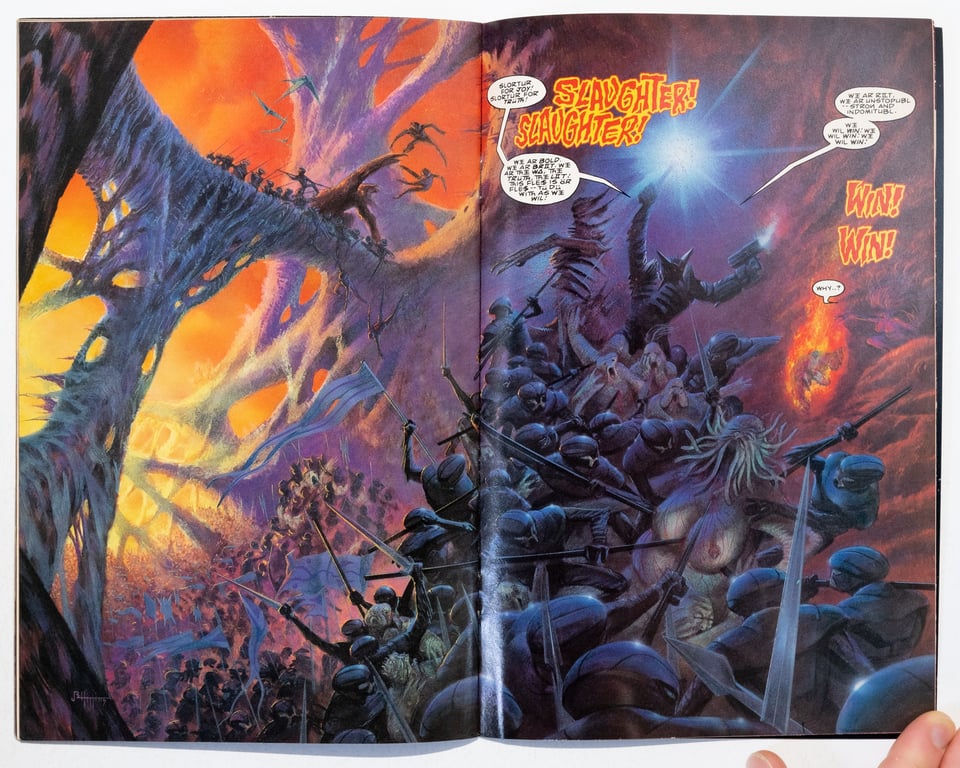

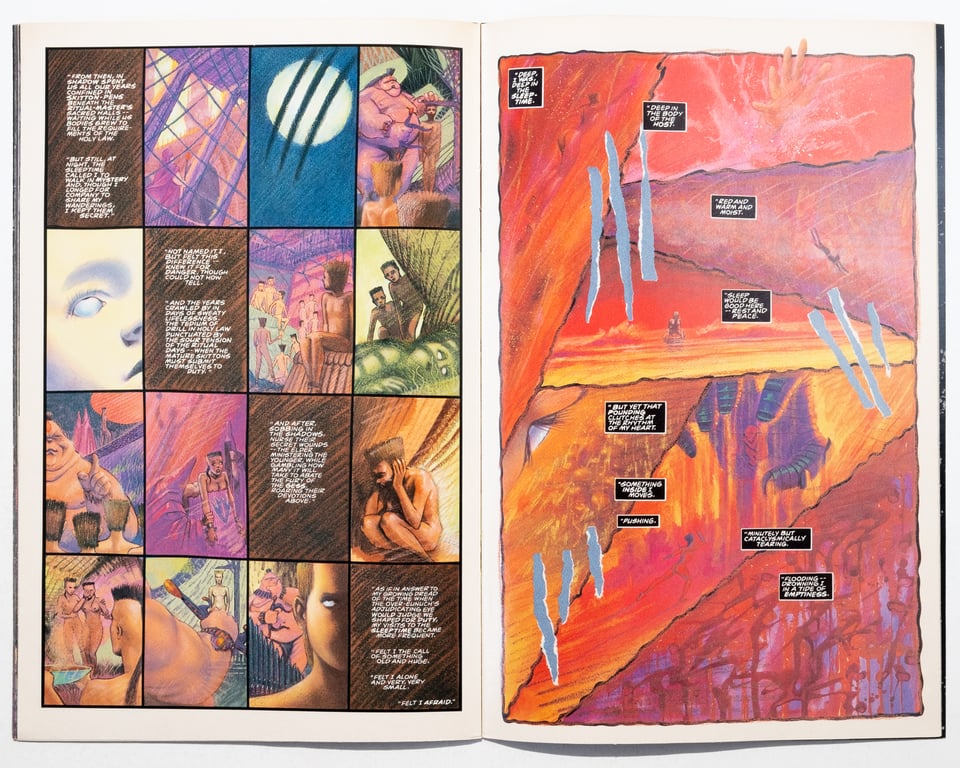

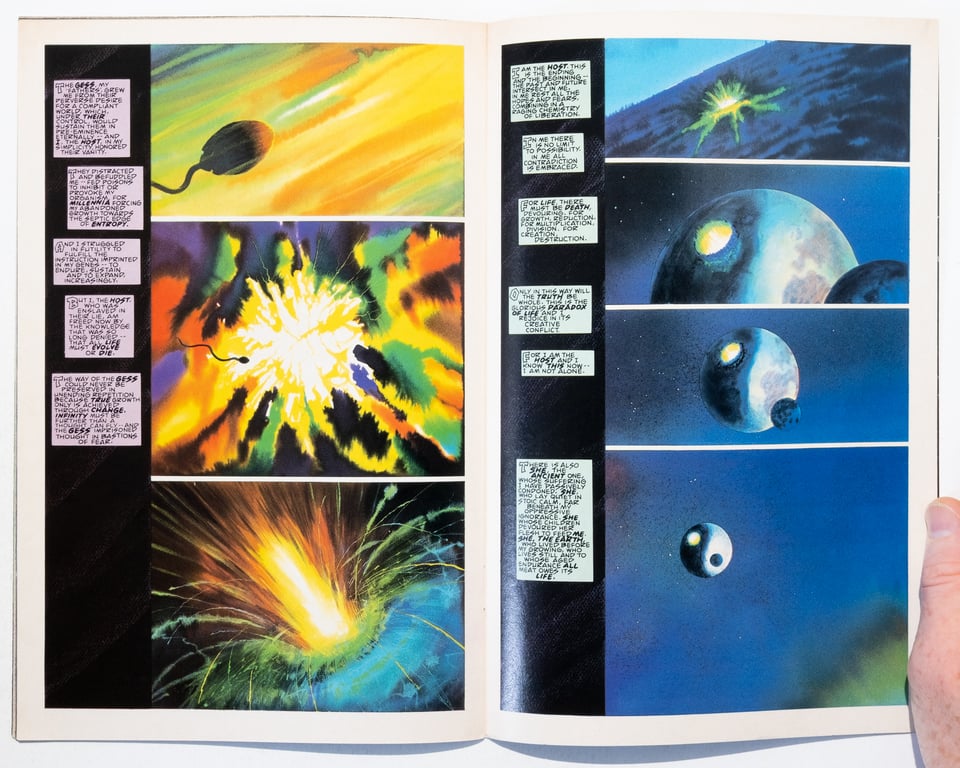

World Without End is a six issue miniseries written by Jamie Delano and fully painted by John Higgins. It was published by DC Comics from 1990 to 1991. A collected edition was released by Dover Publications in 2016 that omits many of the incredible covers Higgins painted for the single issues. The series follows a misogynistic religious theocracy that rules over a planet of flesh wracked by environmental catastrophe. It is a beautiful mess of body horror, Heavy Metal style barbarian action, and feminist performance art that masks some pretty relevant topics to today.

Delano was wrapping up his iconic run on Hellblazer and had yet to start his tenure on Animal Man when this book was released. Higgins’ biggest claim to fame is as colorist of Watchmen which had wrapped several years prior. But as we have learned from Lynn Varley and Richmond Lewis, every great colorist is a great painter in disguise. I hope that Watchmen pays all of Higgins’ bills, but if you want to see his greatest work this is the book for you.

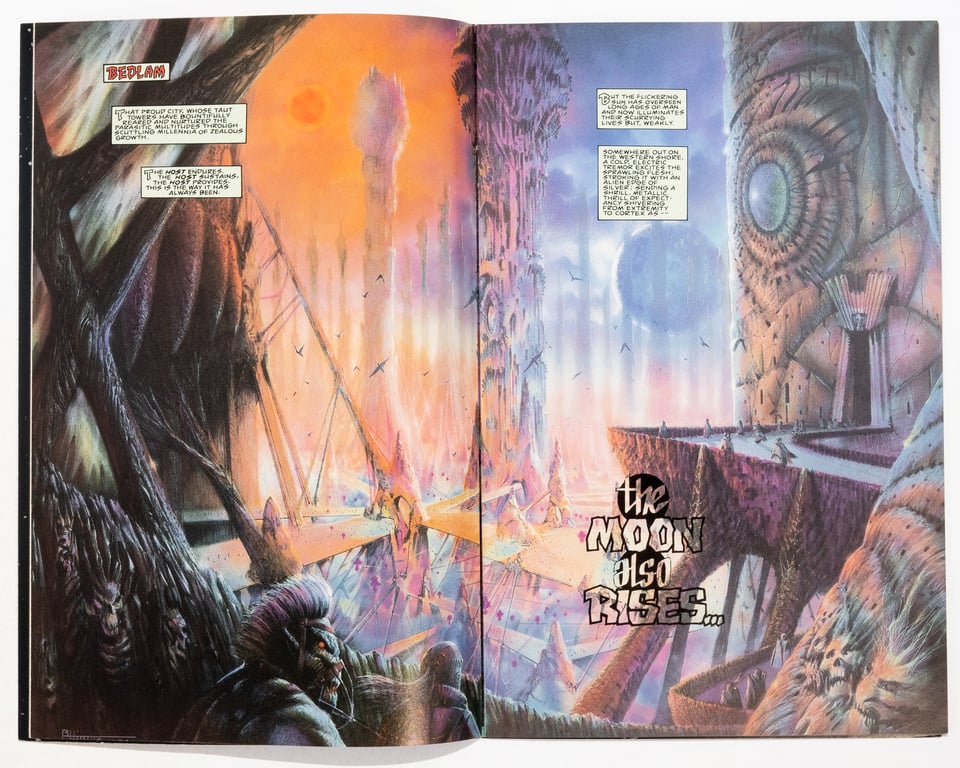

When our story begins, the misogynistic theocracy is falling into disarray after countless years of rule. Known as the Gess, they have survived, even thrived by burrowing into the flesh of the world and manipulating it through complicated eugenics programs, programs that are failing more and more frequently. This is an existential threat to the Gess because they have maintained control over the world they know through brutal subjugation of it. Anything wild or unplanned is seen as an aberration to the Gess, something to be rooted out and destroyed. This includes anything that could be construed as ‘feminine.’ In fact, the Gess only reproduce through this parasitic relationship with the flesh of the world. Naturally, there is a creature living in the wild country that surrounds the Gess capitol city of Bedlam This abomination is creating other monsters in the wilderness that threaten the unilateral authority of the Gess. If you’ve read this far and realized that the ‘abomination’ is a woman (named Rumour) you should give yourself a cookie.

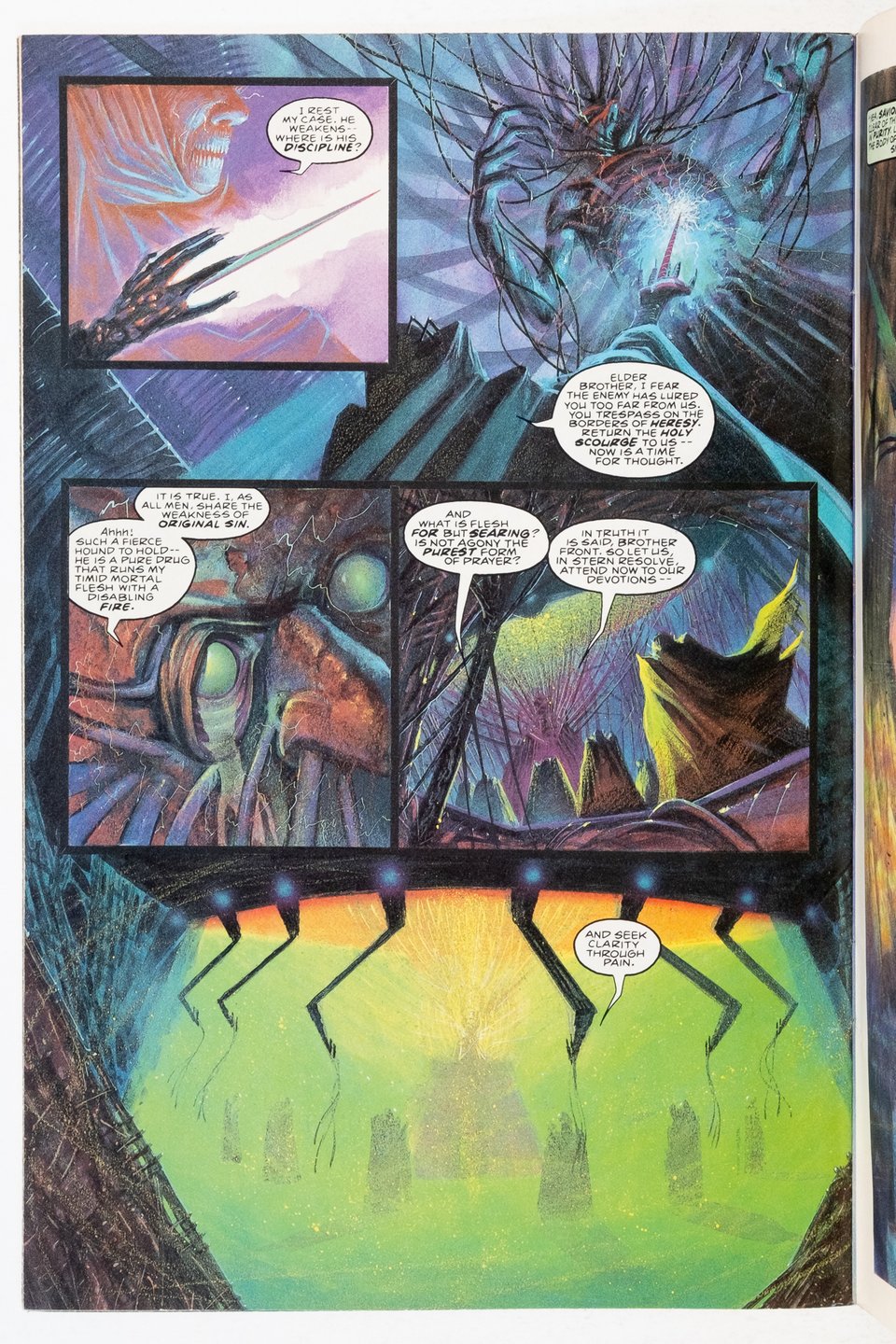

In response, the Gess create their own angel of destruction—Brother Bones—who is Rumour’s opposite. Whereas she naturally and wildly creates from the land, he worships pain and seeks to destroy. He is bent on her destruction for the simple reason that he thinks it threatens his existenc— a kind of incel angel of death. As the story progresses, Rumour and Brother Bones pursue one another across the landscape. Rumour discovers an apparently idyllic community of women called the Scarlots whose existence is threatened by the Gess. In issue 3 we learn the origin of this world, the Gess, and the Scarlots (spoilers ahead).

The titular “World Without End” of the story was constructed millions of years prior as a luxury yacht by the wealthiest men of a dying planet. It was made of living tissue in order to sustain its passengers through whatever catastrophic conditions may come. The Scarlots were sex workers brought aboard the yacht, meant to satisfy the sexual appetites of the men who bought passage. In the millennia that have passed, this history has mostly been forgotten as the ecological collapse and biological systems of the yacht changed the Gess, the Scarlots, and the world itself into unrecognizable, fleshy shapes.

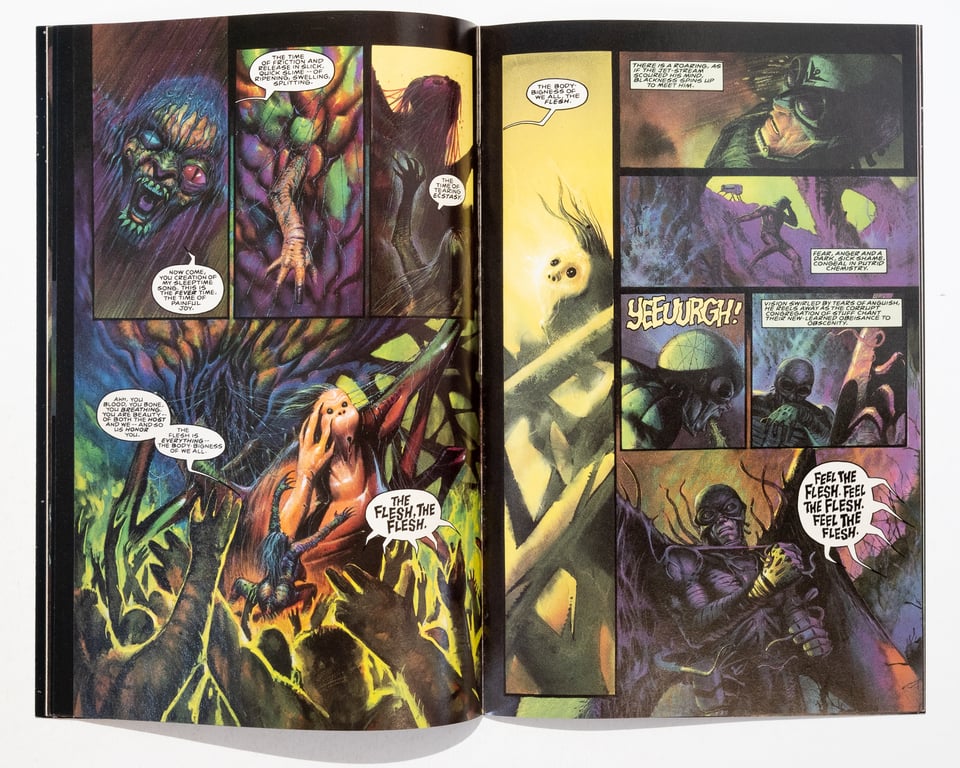

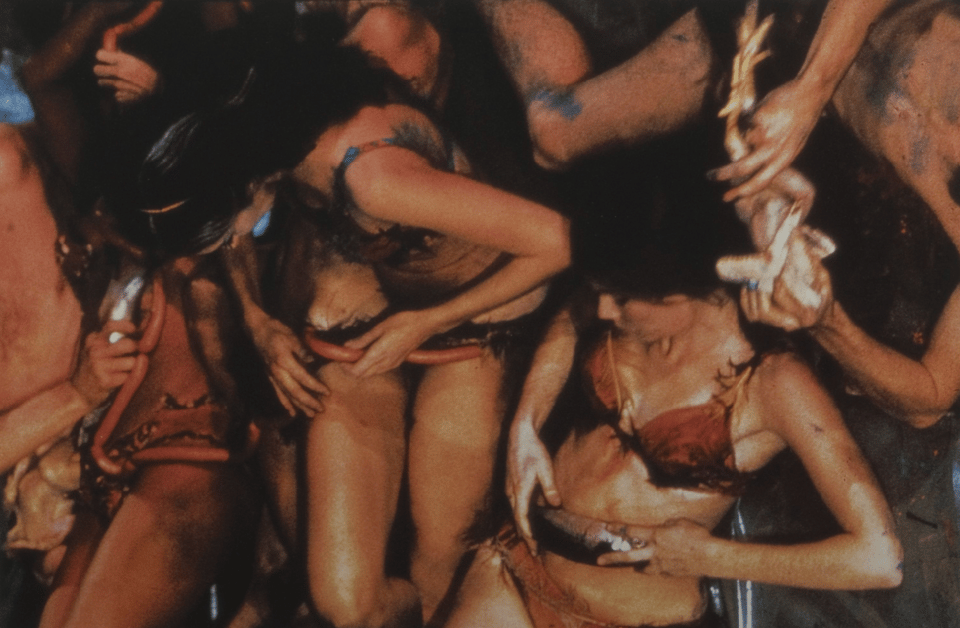

Delano’s conception of a world made of flesh, with the accompanying bodilyness that phrase conjures, is reminiscent not only of the (at the time) nascent body horror genre in film, but also the performance art of artist Carolee Schneeman, in particular her 1964 piece “Meat Joy” in which a group of performers writhe around on the floor covered in raw chicken breasts, sausages, and other, well, fleshy things. The point of the piece was to embrace the muck, the fluids, the bodilyness of life that makes us human. Schneeman conceived of the piece as an “erotic rite” that addressed the binary she herself was put in as a woman artist in the 1960s. She could either be a “‘pornographer’ or [an] emissary of Aphrodite,” roles that “function as dumping grounds that cloud constructed differences between the erotic and the obscene.”1

Consequently, this worldview aligns remarkably well with the one that informs so much of the body horror genre. Perhaps this is best summed up when we observe that David Cronenberg’s (the father of body horror) preferred term for the genre is “body beautiful” in order to reflect his belief in the beauty of the transformation, no matter how grotesque it may appear to straight audiences (Is it any wonder that some of the most innovative additions to the genre in the 21st century have been explicitly rather than implicitly queer and trans coded?).2

In films like Cronenberg’s Videodrome or his modern masterpiece Crimes of the Future, our physical bodies must change drastically in order to transcend to the next stage of humanity and live a good life. This change is almost always messy, but rather than shy away from that, Cronenberg urges us to embrace it for what it is: a radical reclamation of human agency to determine our own identity. Whether or not the characters can accept this informs the central conflict of his films along with the ever present danger of authoritarian control of these new bodies. These themes are present in World Without End as well but Delano takes it a step further.

In Delano’s narrative The Gess are the end result of billionaires embracing (literally) toxic masculinity. They are the parasites of the new flesh, too blinded by jealous infighting to recognize the need for change, yet so fearful of any difference they would rather create the agent of their own destruction than adapt themselves to a new way of life. By contrast, the Scarlots are portrayed almost like a parody of the “divine feminine” brand of feminism that frequently teeters over into TERF right wing territory that (once again) seeks to control other people’s bodies for no apparent reason. In both societies we see a replication of the same gender binaries that necessitate their destruction. It is noteworthy that the Gess find Rumour so revolting in part because she is creating life from the flesh outside of their rigid strictures, and in turn her destruction of the toxic world they have created is (of course) a profound act of creation.

Gender essentialism has been a consistent specter in my read through and the writing of this piece. To be clear, there is not even a whiff of trans awareness in the text, but that has never stopped people from reading subtext in comics before so why start now? Both societies—Gess and Scarlots––exist on a brittle foundation of sexual control that would (I assume) violently stamp out anything that doesn’t fit expectation, thus the necessity of the book’s final act of destruction. And while Delano resorts to much of the same essentialism in his conception of liberation, there is undeniably a queer sensibility to his critique not only of the Gess, but the Scarlots as well that is only further complicated by the two groups original power dynamic. To be perfectly honest, the idea that a group of wealthy men would turn on the sex workers they brought aboard their apocalypse pleasure yacht is the least fantastical plot element here. The fascism of the Gess is self-evident. That of the Scarlots is harder to discern, but still present. Delano successfully shows that the end result of an ideology of control will only result in a society’s self imposed destruction.

So after all that, is it a good comic? Well, mileage may vary, but I would say YES! Like I said at the top, it’s a bit of a mess. But I’ll be damned if it’s not a compelling mess that resists easy categorization with a lot to dig into. Ultimately I think this comic deserves to be called a true cult classic, ready for rediscovery.

NEW ARRIVALS

These and many more are available online! click through to browse and consider purchasing something to help support my writing!

Schneemann, Carolee. “The Obscene Body/Politic.” Art Journal, vol. 50, no. 4, 1991, pp. 28–35. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/777320. Accessed 15 Nov. 2024. ↩

Petrie, Raine. “[Pride 2023] David Cronenberg: The Transsexuality of (Trans)formation.” Gayly Dreadful. 15 June 2023. Editor’s note: I am committing a faux pas by citing an article that quotes Cronenberg rather than the direct source. I am doing this because their essay was incredibly helpful in the writing of my own piece and I wish to acknowledge their work Go check it out! https://www.gaylydreadful.com/blog/pride-2023-david-cronenberg-the-transsexuality-of-transformation ↩