Marsh & The Magdalena, Dr Emily Friedman on Actual Play, the 18th century, other things.

Ahoy, and welcome to the TEETH newsletter. This is an (aspirationally) weekly report about our travels on the TTRPG-seas, written and compiled by implacable leviathan, Jim Rossignol, and guano-spattered wreck, Marsh Davies. Why not jig on over to the TEETH Discord and do something sufficiently nautical to satisfy the strained theming of this introductory paragraph?

Hello, you.

Links

Interview: Dr Emily Friedman on the emerging art of Actual Play and wallowing in the muck of history

Hello, you. Marsh here today.

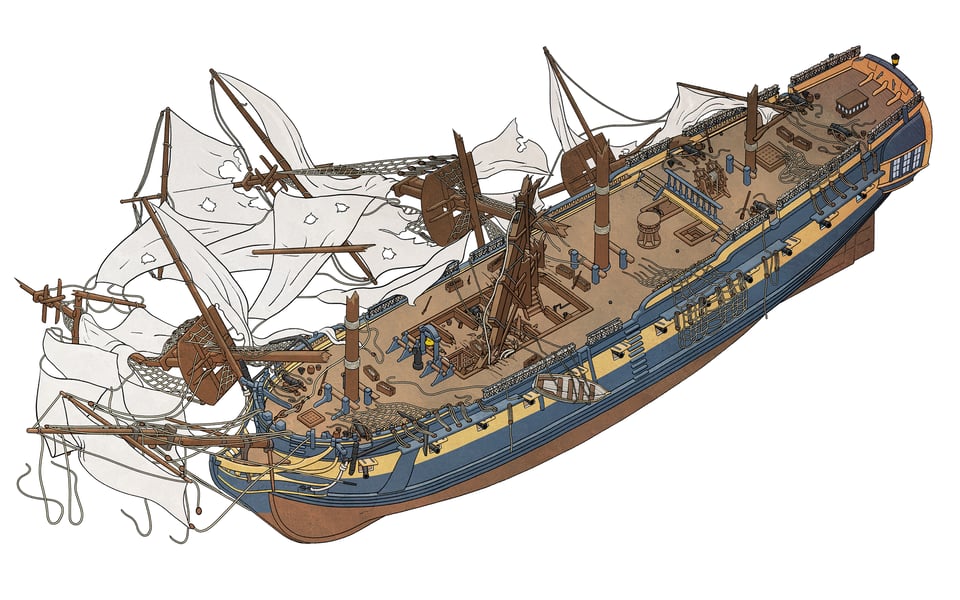

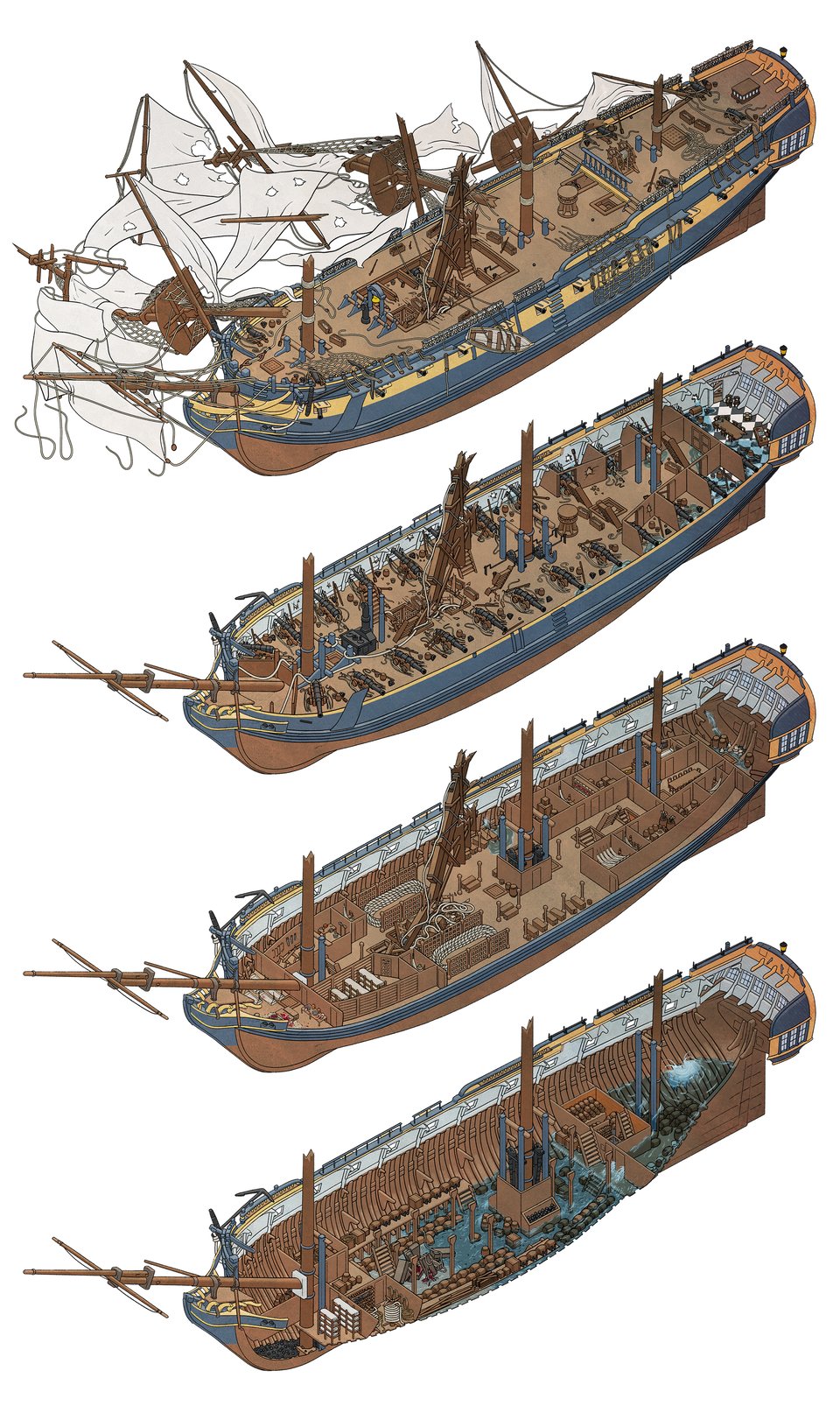

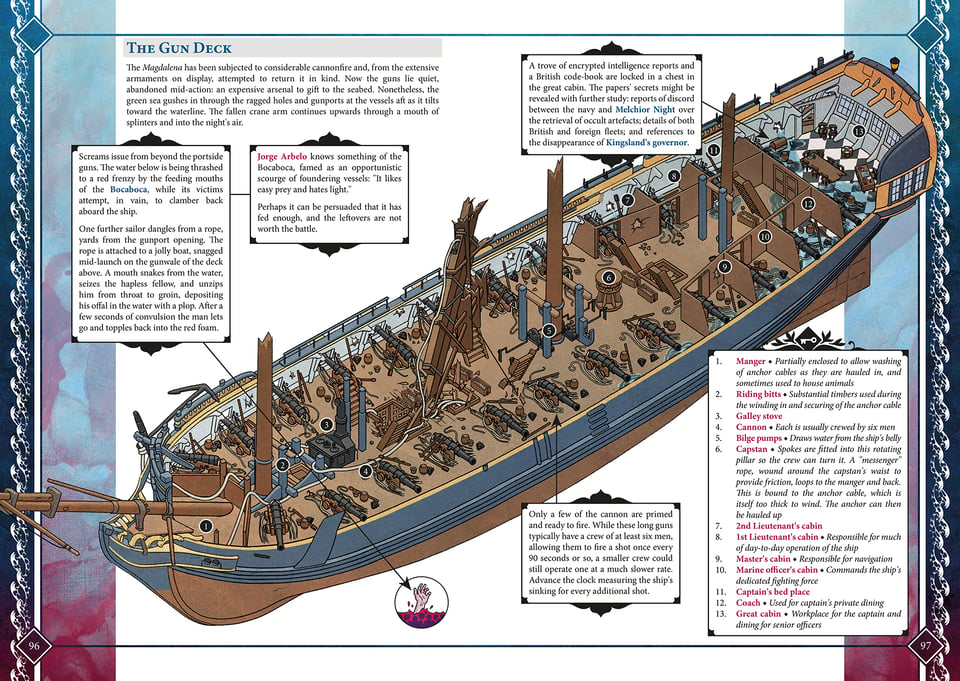

Behold, the ill-fated Magdalena, my personal nemesis. The four diagrams that comprise this ship have taken me over a month of drawing interspersed with research, occupying nearly every hour from waking to sleeping—and it's still wrong in a dozen ways I'm hoping people won't notice, or at least be kind enough not to mention. However, seeing as players will find themselves aboard this doomed vessel in the starting scenario of Gold Teeth, it felt important to realise it as well as I could.

Alas, there are not many 18th-century 5th-rate frigates knocking about these days, and descriptions of them tend to be either too technical for me to understand or too vague for me to draw. I have several books that meticulously model the workings of 18th-century mega-ship HMS Victory, down to itemising every plank of wood, but this is only so useful: the Victory is an anomalously large ship, one of the biggest and most expensive ever built. The tonnage of shot it could fire from its cannon is greater than that of the British arsenal at the Battle of Waterloo. Needless to say, its construction and operation were a bit non-standard. The ship I needed was several decks smaller and more mundane. After several false starts adapting what I'd learned from these books to an imagined vessel, I realised I needed something more substantial on which to base the drawing—I turned to 3D model emporium Turbosquid, where I purchased this fantastic model of the HMS Surprise by Redben Studios.

Problem solved!... Partly. Though it's a beautiful model, and very detailed in some respects, the more I worked with it, the more I realised it omitted or fudged (and I mean no shade here; I too omit and fudge things, just not necessarily the same things). It also contradicted other information available about the Surprise—which was a real vessel, later given a new fictionalised life in the books of Patrick O'Brien, and exists now as the Rose, a different tall ship that was purchased and modified to look like the Surprise for the film Master & Commander—something to which our Kickstarter budget did not quite stretch. While the model gave me a convincingly detailed hull, weather deck and rigging, there is no interior detail at all. I had to supply that—again cross-referencing a number of contradictory and semi-relevant sources to figure out how to fit everything in plausibly. In doing so, it made me reconsider some fairly fundamental things about how the decks are connected, and I learned a good deal more about bilge pumps and anchor cables than I expected to. I am indebted to the talented nerds of the Ships of Scale forum, whose past discussions helped clear up a lot of questions, and videogamesman Ian Boudreau, who generously shared his practical knowledge of sailing on tall ships.

Hopefully the end result is, if not exactly accurate, at least informative and evocative, giving players brisk a rundown of what 18th-century ships contained—all of which which they can absorb in time before it sinks, ideally without the players still on it. You can see how it looks annotated on the page below, but beware spoilers if you intend to be a player rather than a GM.

Anyway, I'm glad that's over and I have been granted brief release from ship-drawing prison, finally able to return to the long and increasingly urgent list of other things that need to be completed before we publish the beta. It is coming though. Hopefully the final voyage of the Magdalena is proof!

-Marsh

Links!

THING OF THE WEEK: is issue 7 of WYRD SCIENCE. Jim is in it! He writes about digital game phenomenon Caves of Qud and learns of its relationship to 90s RPGs from the creators.

Sometimes I think a blogpost is worth it for the title alone. Downtime Demands of Sentient Weapons: Or the Care & Feeding of Excalibur is probably two such titles, realistically.

Like the look of this adventure by Chris Bisette, where Mork Borg characters start at the bottom of a dungeon and crawl their way out.

Wrestling RPG World Wide Wrestling is getting a second edition.

Asher’s Ridge looks fantastic. “Inspired by Twin Peaks, The X-Files, Stranger Things and more, Asher's Ridge captures the twists and turns of your favourite paranormal television shows.” And it uses Scrabble tiles somehow.

ITV have posted the full series of The Prisoner on YouTube. If you want to understand Britishness then you must have seen this series at least once.

Interview: Dr Emily Friedman on the emerging art of Actual Play, celebrity, playing around in the muck of the 18th century and more!

Technology barrels along at an ever-faster pace, transforming media before society even recognises that it's happening. We are constantly playing catch-up with new tech, new trends, new forms of expression, while the bodies that might previously have anticipated, analysed or even regulated the already-here future are asleep at the wheel. In fact, for much of my career writing about games, they've often actively resisted attempts to understand our current moment, seeing these emerging forms of media as somehow trivial, unworthy of study. Of course, it is exactly this stuff that requires the most urgent and sensible analysis! In our own hobbiest corner of The Now, we have people like Dr Emily Friedman to thank for a growing body of work that looks at the explosion in popularity of Actual Play, and the effect it has had on roleplay, performance and internet culture more broadly. We must treat being a goblin on the internet telly with the same seriousness as we study the work of Jane Austen—and, happily, Dr Friedman is an expert in both. I caught up with her to chat about one particular intersection of her interests that is especially relevant to Jim and I, the 18th century and roleplay, but immediately got diverted into other fascinating topics.

Davies: Could you introduce yourself and your scholarship?

Friedman: I'm Dr. Emily Friedman. I'm currently Associate Professor of English at Auburn University, where I was originally hired as the late 18th-centuryist. The "long 18th century" runs from 1660 to 1835, give or take, and I usually cover the back half. Over my career, that remit has grown to encompass the long 18th century all the way to today. And since 2020, when my work on never-published manuscript fiction was stymied by the COVID-19 pandemic, I became one of the leading and most senior scholars studying Actual Play, the practice of recording and performing role-playing games for audiences.

Davies: I actually don't want to talk too much about Actual Play [Ed—this is a lie, we absolutely talk about Actual Play, loads] because I know you've covered that a lot already, not least on the Yes Indie'd podcast with Thomas Manuel, which everyone should listen to.

Friedman: It is amazing how well that interview has held up—as well as my other early interview in the field for Secret Nerd with Navaar Jackson.

Davies: What do you mean? Did you expect the last couple of years to have changed your opinions a lot?

Friedman: It's interesting to think about the position I was in when I was doing those initial interviews, which is very much as an academic outside of both TTRPG design and TTRPG performance. And the nature of the beast with TTRPGs is that the field is so small, game studies is so small and game production is so small that you become an insider very quickly if you've got anything we might think of as cultural or intellectual traction or clout, right? I have a tenured position at a research university, so I kind of came in the door with—unbeknownst to me—a certain amount of power and authority. I didn't realize what I was bringing to the table! And it's been only in the last maybe 18 months, by entering the kind of in-person spaces of fieldwork and playtests and conventions, that I have discovered the full nature of my reputation, as well as something like parasociality—a thing that I am trying to avoid having for other people. I didn't realize that parasociality actually comes for us all in some way, shape or form. For all of us that make things in public, be it game designers or Actual Play or academics, there is a little version of ourself that walks in front of us into some rooms and lives rent free in some people's heads. And sometimes that's a nicer, cooler version of who we are. And sometimes that's like a monstrous version of who we are. And we can't control either of them. So you just try to make spaces where people can kind of park those versions of themselves at the door and we can all try to be as authentic together as possible. But I'm already thinking about my future research: about micro celebrity and how we use the word friendship. Social media, networking and collaboration has trained us to think about friendship in particular kinds of ways: we are so focused on the threats that come from people who don't know us and misunderstand us through parasociality or just internet life. We don't think about all of the ways that our collaborators, our friends, our colleagues are more capable of hurting us. Most of the time, when we're making games or playing games, we aren't doing it alone: we're doing it as an act of trust and faith over a substantial term with other people that we care about.

Davies: Well, hold that thought! We'll come back to the social or parasocial aspect of Actual Plays. But just to react your rise to great authority within the field of TTRPGs—

Friedman: Oh, geez.

Davies: It's a very slow hobby. People take a long time to play games. Unless you have two regular sessions a week or more, playing different games, then you're just not going to experience the medium in any kind of breadth. So your insight as an academic immediately becomes valuable because you actually have that top-down perspective on what's out there and you're able to devote the time to understanding this stuff in a much deeper way than I think most writers or creators do or can.

Friedman: That is the beauty of academic freedom as it currently exists and hopefully will continue to exist. You have the ability to do slow-braised takes. But it's definitely my ping of imposter syndrome. And that's also because, when I think about the people who have mentored me, it's people like Evan Torner, who's been in the scene without break since he was very young. He is deeply immersed in the Nordic LARP scene in addition. And then of course, the other person who I think of as an interlocutor is freaking Quinns, who has decided that he's going to make up for lost time by doing three games a week or more at any given time.

Davies: Yeah, he's going to die young. That's what we're discovering.

Friedman: Sure hope not! Some of the most interesting writing he's doing is about trying to find that equilibrium and balance, which I think is resonant for a lot of us.

Davies: You've written about how Actual Play falls into a broader interest you have in how new art forms emerge from new technologies and technological change. I was wondering if you could pinpoint the elements of newness that allow Actual Plays to exist.

Friedman: So it's a series of what we call affordances. One of the very first Actual Plays, which I have right next to me, is this 2008 DVD-ROM of Lovecraftian Tales from the Table that I just got from Noble Knight Games. It actually contains recordings from several years earlier of the Bradley Players, who started out as the Bradley University Role Playing Society, or BURPS. And they accidentally recorded about 30 minutes of D&D in 2003 as part of their college session.

Davies: Accidentally?

Friedman: They were testing the MiniDisc recorder and they didn't know that was still left on. At least, this is the story that they tell. And so then they upload that file. And of course, remember, this is the early noughties, so download times are still pretty long, but it was downloaded several thousand times in the first week. You've also got these traditions already floating around of people playing in front of audiences: you've got college campuses doing battle royales in the 90s. At Gen Con, you've got Killer Breakfast, where volunteers would sign up to go through this meat grinder and basically die immediately in front of an audience. There's one set of recordings from 2007 where Gary Gygax is part of the celebrity team. So playing in front of a crowd has a long history, as does people writing accounts of their games through fictionalisation or in the style of [legendary TTRPG design community] The Forge, where they use the term Actual Play to mean, "We're a theory-crafting group of folks, so if you're going to use evidence, we want evidence from your actual play from your actual table, as opposed to you bullshitting."

So when recording technology and internet download speeds and platforms start to emerge to allow the hosting of audio and video, you see these kinds of recorded play come up, as well as others. YouTube originally has a low limit on how long recordings can be, which becomes this really interesting constraint: like, here's 10 minutes of play but it's annotated, or a Warhammer-style battle report. So you've got entertainment, record-keeping, you've got a little bit of pedagogical, you've got some play testing—all of those things become a soup that's later going to get called Actual Play. It's a soup that is then given its leap into the mainstream, partly because of the development process of Fifth Edition D&D and Wizards of the Coasts' collaboration with Penny Arcade. Then there's the rise of Twitch, which is what allows Critical Role to build an audience because they're on the front page of Twitch.

So it's the story of changing platforms, but then the biggest increase in terms of audience and participants is 2020. We're all stuck at home and we have better microphones and cameras than ever before! You've got a rapid increase of people who can make the stuff and a rapid increase of people who need that kind of second screen activity. So all these elements braid together: changing game systems, our relationship to play, technology and whole lot more.

Davies: The pairing of, or interdependence between, those technological and sociological changes is really interesting. I want to posit some pure bullshit at you, which is that those things fundamentally change something about the way we think about ourselves, our interior experience, basically. In the same way that when private reading becomes the dominant form in which the written word is ingested, suddenly that changes a huge amount for both the author and the audience because much more is being asked of the audience to transform this text into a drama within their own mind. And the author is no longer physically present to shape its reception. I was wondering, is a similar thing happening with Actual Play? You have these concepts like bleed, you have parasociality and you have fictional characters directly articulating their motivations to the table, articulating their interiority to the audience. Does that kind of combo shake things up in the way that the invention of print did for private reading?

Friedman: It's really interesting to think about the impact of Actual Play. Every once in a while somebody says the Mercer Effect [whereby home games are held to a professional standard of Actual Play, heavy on improv and voicework], and I'm pretty skeptical about that. Actual Play has a diversity of play practices that is bigger than just the largest shows. People gravitate to the things that resonate with what they want to do. So yeah, there are a hell of a lot of theater kids that gravitate to Critical Role and Dimension 20—but which came first, right? Is it the influence of those Actual Plays? Or is it just that those Actual Plays are making more visible something that was always present in people's home games, but that you know you weren't going to necessarily see in your friendly local game store or at a convention? I haven't seen a lot of satisfying evidence, aside from a lot of people articulating anxiety that they are being held up to the expectation of being Matt Mercer. But, uh, question mark, right? I think what's more striking to me is not connections of influence, but again, that question of platform. For a large number of my research subjects who I talk to, especially in the post-2020 cohort, their online game is their home game. They have never or have not in a very long time played face-to-face, except perhaps in performance contexts, like at conventions and things like that. Their primary experience is online. And so, for them, the difference between home game versus performance is whether someone pushed the button on OBS or not.

Davies: Something I've noticed playing with folks of a younger generation than myself, whose practice of playing games has been more heavily informed by Actual Play, is that they're much more demonstrably appreciative of other players. And perhaps it's because they have picked up a style of play which is much more sensible of an audience beyond the table, but the result is positive communication with players immediately around the table.

Friedman: Yeah, I mean, I think the thing that we forget so much is that there is an audience at every table—which is the other players, right? One of the first pieces I did for Polygon was me going around and asking people who I'd never met before, what makes a good Actual Player? And it was all about listening. It was all about being the good first audience to what was happening at the table—because you're the audience surrogate in that way. And so how you respond is the way you hope the audience is gonna respond. It's interesting to think about, especially in terms of the parasociality, like how much is Actual Play shaped by that kind of anxiety about audience. When I did my research interview with Brennan Mulligan, like one of the things that he was very insistent on is that the audience can smell a fake and a phony. If they think you're playing to them as opposed to playing to the table, they will reject that as insincere.

Davies: The way that people project themselves into their art, and specifically in Actual Play, and just in role-playing in general, is really interesting to me. And I think that's what I was driving at with the shift to print. There's a thing that happens to Chaucer across the course of his career. When he starts out his work is not as widely disseminated. Print has not really kicked into gear and put his work into people's hands to read privately. So his work is very much still within that oral tradition. But, by the end of it, his work includes a lot more self-insertion: he's constantly referring to himself in his later works, whereas that is notably absent from his early stuff. I wonder if that's a reaction to the fact that people are reading his work privately, and he feels a need to kind of re-inject himself into the text in order to maintain the kind of presence he had when he was there, you know, reading it out himself. I can't help but feel like something similar is going to happen or is already happening with the way that we insert or assert ourselves in roleplay: it's such a complex negotiation of different selves, and then Actual Play adds that extra projection onto an audience beyond the room as well. It's got to change the way we think about ourselves as a presence within our art—but I don't know how yet!

Friedman: One of the beauties for me of Actual Play is getting to watch a thing being made before your eyes. The combination of the character and you as a person, you and the dice, the way the elements of chance give you the alibi for not conforming to narrative expectations and traditional structures. But I think the self being visible and legible is something that people don't want to talk about. People dismiss Actual Play as being created by influencers an awful lot. And what they're getting to, I think, is the idea that the annoying part of Actual Play is that you have to like the people who are in your ears or on your screen in order for you to even make the jump into caring about the narrative. I don't have to like Jane Austen as a person in order to read a Jane Austen novel, but I do have to tolerate an Actual Player and their troupe's performance. We don't talk about having to have natural rizz in order to succeed, even at a marginal level. No one likes thinking about that as a thing that should be counted, especially not in a nerd space—God forbid, right? But the idea that that might also be a skill that's cultivated doesn't feel very authentic. So it's an impossible double bind, right? It's sprezzatura, really—the art of effortlessness. But we don't want to talk about that because then we'd break the kayfabe.

Davies: You mentioned Jane Austen so I'll take that as an opportunity to segue into talking about games set in the 18th century! What attracts you to that time period?

Friedman: As a teenager in early college, the 18th century appealed to me because it was presented to me as a moment of important change for the Anglophone world and the Western world in particular. It's not a coincidence that the period that I study here at Auburn is referred to as the age of revolutions. You have the French and American revolutions. You have the Haitian Revolution, arguably the most important of those revolutions. Then right after the long 18th century, you've got many European revolutions, some of which are successful, some of which are not. And of course, on the other end of the 18th century you have a time period in Britain that is marked by the death of kings and the Glorious Revolution: the revolution that has no bloodshed. It completely changes the dynamic of power. And you have the Industrial Revolution gearing up, too, right? And so if we want to think, for better and for worse, about what comes next, the 18th century is a really good place to do that.

And in terms of writing there's the emerging mass-market. My dear friend and colleague Megan Peiser has written about the ways that reviews come into being in this period, radically transforming the ways people read. Anthology and the Rise of the Novel is a great book that's about how excerpting practices create the early canons. I love the challenge of very long texts: reading Samuel Richardson prepared me for Critical Role! I've read Sir Charles Grandison multiple times. It was Jane Austen's favorite novel, and Samuel Richardson's least-loved third novel. It's about a perfect man—scare quote, scare quote, scare quote. It's the world's greatest breakup novel, and it ends in polyamory! I find it particularly fascinating because Richardson is a guy who desperately wanted to be the great didactic author, writing novels that would commit people to very boring mainstream Protestant morals, as the middle class is being imagined into being, but he ends up doing something explosively different. These are epistolary novels, so they're in first-person and all from the perspective of heroines—even the one about the perfect man. He doesn't write; everybody's writing about him. But the characters we do hear from are these women that Richardson tells us are perfect, but what we actually see is that they're human. Richardson, a 50-year-old roly-poly British man, successfully writes a 15-year-old girl's sense of isolation, anxiety and vacillating feelings about someone she's attracted to, but also being sexually harassed by, and all of the kinds of mess that inculcates, with misreadings and counter-readings that are built into the text itself because the character contradicts herself. She is a teenager in a very real way. And that's amazing to me. Like when something is an artistic success precisely against the express wishes of its creator, sign me up!

Davies: I have to read this!

Friedman: Yeah! He would spend the rest of his career—like the last thing he does is make an index that's like, here's all the moral lessons you should learn. Like, here's why breastfeeding is great, see Clarissa, page blah blah blah. I love that shit. And I'm fascinated by the state of women writers. A great forgetting ensues in the 19th century: we forget that the novel was a form that was promoted and dominated by women. Austen herself knew it. She tells us in Northanger Abbey, the lineage that she draws from. It's extremely radical, revolutionary stuff; it's counter-revolutionary, deeply conservative stuff; it's everything in between. And in that moment, there's the revolution that doesn't happen in the 1790s: Britain is looking at America and France going, could this be us? Can we change the fate of women, of franchisement? Could heads be rolling over here? And you get to see in real time those kinds of anxieties playing out.

And it's also the moment of the worst inhumanity that the West has ever perpetuated, right? Which is the chattel slave trade. And to see both explicit and implicit impacts on culture in both the United States and Britain—the empire upon which the sun never sets—is all fascinating to me. And for me as a teacher, what's really useful here down here in the Deep South is to be able to use this kind of moment as a way of talking about things that are hard to talk about in our local context. We can point to the fact that a man of that time could just as easily be an abolitionist as they could be deeply immersed in the bloody, bloody trade. We don't want to overstate the case, but there were people who were against this even then; that opposition was a moral option was not unthinkable, and that is really powerful in terms of all kinds of movement work.

Davies: Right. I'm happily addicted to Finding Your Roots with Henry Gates Jr. and it's fascinating to see his guests grapple with the revelation that they had slave-owning ancestors—and how, occasionally, some of them then equivocate and say those ancestors were people of their time, and who are they to judge? But no, the evil of slavery was readily apparent even then. There were people saying as much. Morality wasn't completely alien to the past.

Friedman: Yeah, one of the glorious things about scholarly publishing for classrooms is that we are recovering not only abolitionist voices, but the voices of Black folks. The great, very teachable, very readable novel that I often assign alongside Austen is a novel that we're reasonably certain was written by a woman of color called The Woman of Color, which is the story of a biracial heroine who returns from the Caribbean to meet the white part of her family as she needs to marry her cousin in order to fulfill the terms of her dead father's will.

Davies: Oh boy.

Friedman: And there are really important Black intellectuals operating in London who are advocating for abolition as well as just countering the general economic logics of chattel slavery, which is incredibly important in the period. It wasn't hidden. So bringing this into the classroom as a kind of responsible corrective is still really important and of course is more important than ever at the time of this recording. God help us.

Davies: Let's talk about how that intersects with your interest in TTRPGs. You've read and played a lot of historical RPGs. Do you have any tips for how RPGs can convey a meaningful historical reality in such a way that it survives being played—by people who might not share a historical understanding of the period?

Friedman: The thing that's really hard for me is when something makes the claim being 100% accurate in some meaningful way. And then all it takes is one thing for you to lose it. At the start of the pandemic, my colleague Emily Kugler at Howard University and I took on playing 18th century video-, board- and analog games as our little side project, a thing that we continue to do. And the reason these games are interesting is because we think they're the forefront of what adaptation can be. What I'm interested in is not faithful adaptation, but interesting adaptation: thinking seriously about what the 18th century truly was, warts and all, and slicing off just a little bit of that, beyond the fantasies, beyond the kind of cool clothing or whatever, and getting down into the muck. And this is where I say nice things about Teeth, right? The appeal is not that it's a 100% authentic world, but that it's engaging with the muck of the period, I think in really fruitful ways.

We just got back from the University of Southampton where we were presenting a workshop on games set in the long 18th century—focused on Austen because the conference was Global Austen, but we wanted to say that Austen is often one of the least interesting subjects that historical games tackle, because "Austen" can be just another way of saying "Bridgerton": a kind of dainty and demure marriage plot. But my favorite Austen game is a game that has never been published, that exists only in the oral convention tradition. It's a Kagematsu hack called A Single Man. In Kagematsu, the original version, Kagematsu is the hero coming into a village. Kagematsu is always played by a female identified game master. And the rest of the players are the villagers, usually village women, who are trying to win his favor, so he will go and fight the thing that's threatening the village. And so it's a game about power. It's all about contested rolls: you're not trying to do something to him, you're trying to get him to do something for you. In the Austen hack, which was created by Melissa Spangenberg, you're trying to get the single man to give you a sign of growing affection and ultimately a marriage proposal. Players know if their rolls are successful, but what they do not know is whether they have won with love or pity.

Davies: Ohhhh. Shit. That's brutal!

Friedman: So at the end, an offer is made—one person is going to get the promise—but have they won a happy ending or have they just won an ending?

Davies: That's really good.

Friedman: For real. I've had my students play this in my grad class last year and had a very weird moment because I realized with dawning horror that the nature of power is such that, while I am a woman, I can't run it for my students. I have the power. So thank God one of my students is like a second generation TTRPG nerd and female-identified and was willing to run it.

But yeah, it leans into the fact that Austen is really about power and desperation. The Bennett sisters need one of them to get married well in order to succeed. So while most Austen games are romance fantasies, in the same way that most, you know, D20 games are power fantasies, I gravitate to the games that immerse us in some aspect of the fuckery of the 18th century.

Davies: Talking of which, we're stepping into even more murky water with Gold Teeth, because, being set in the Caribbean, slavery is an inescapable part of that world. Omitting it would be dishonest—and, in fact, engaging with how powerfully terrible it was is important to me. But of course there is a tension: how do we present it—in a game—in a way which is not exploitative?

Friedman: Mm-hmm. I think a few days after we played A Single Man, I found myself playing Julia Ellingboe's game, Steal Away Jordan, in which you are playing enslaved people with a GM who represents the apparatus of white supremacy and the logics of the plantation. You've been sold down the river and you're trying to get out and your chances of getting out are low and get only lower—in terms of the actual dice pool. I played that with an all-white table, in that way that you can do in a private space, but I've talked to a bunch of Actual Play creators about whether they'd play Steal Away Jordan for an audience and under what circumstances. And it's a really thorny question. If it's an all-Black table, then does it become a spectacle of Black pain?

Davies: Right.

Friedman: But on the flip side, if you have an all-white table, then something materially gets lost and potentially fucked with, right? There aren't good answers. And there's a reason why nobody has done an Actual Play of Steal Away Jordan. I think about that a lot. It's one of those games that is in its own category: games that are painful to play but worthwhile to play. It's like niche of niche of niche of niche, but I'm glad they exist. I think that we impoverish ourselves when we don't have those kinds of experiences, if we can't encounter difficult things in the space of fiction-making, whether it's reading a book or playing together with people we feel safe and comfortable with,

But it's hard, right? Most of us would call ourselves lucky to have those kind of folks we can entrust with spilling our metaphorical guts. And to manage that in a way that we can say, after the fact, that nobody was left behind, right? I've been thinking a lot about Meguey Baker's principle that you can't go into a game saying, "We're going to do this," as if it's like a procedure. You can only, in retrospect, say, "We played this way and people weren't left behind." And I really grapple with that. How do we ensure that we care for one another at the table? But yeah, this is not answering your question in quite the way that you want but I think the way we get to that kind of answer is what I see Regency Cthulhu's apparatus at the start of the book doing, what I see Teeth doing, what I see some other games not doing: like Good Society, which on the character creation page says, Jane Austen didn't write about race, didn't think about race, so this game will not have you think about race. And you cannot think about race. It's the Bridgerton problem before Bridgerton. Patricia Matthew has written about Bridgerton and race and the problems of it extensively in a lot of different places that I recommend. And so we don't want to do that, right? We don't want to kind of project our notions of what things should be onto history. To their credit, Storybrewers, the makers of Good Society, have a really beautiful blog post about the choices that they made and the comment section, for once, is something I would recommend people actually read. There's an exchange between Mark Diaz Truman and the Storybrewers folks—they don't come to consensus, but they also don't descend into yelling—but Mark basically says, look, what you have constructed is that I am welcome to play your game as long as I act white, and that's not diversity and inclusion, even though if you look at Good Society it's this beautiful United Colors of Benetton in terms of how its characters are depicted. It's trying to imagine this multiracial, liberatory kind of structure, but keeping the vibe of the Regency. Which is why I love A Court of Fey & Flowers, right? It solves the problem by taking some of the mechanics of Good Society, putting them into a completely different world, which is to say the world of D&D, and having a bunch of mostly BIPOC actors play the game. It is often the element of the fantastic that gives us the alibi to be like, okay, we can hand-wave some of this. With historical material, there's always going to be a nitpicky motherfucker, but the more you can give yourself that kind of crack to let the light in or the gas out, the better off you are. Once we're talking about things like the slave trade or representations of the Caribbean, this is usually where being in dialogue with consultants is really important because there are a lot of ways to trip up. Especially like with Haitian voodoo—are you going to include it, are you going to mechanise it? I feel like I've been been in the middle of any number of conversations about zombies, right? The past is not that far past, but especially in the absence of reparations.

Davies: Absolutely—it's distressingly relevant to our current moment. One last question, because you mentioned nitpicking: you run a game with a bunch of historians. Do have any house rule where you lose HP every time somebody suggests an anachronism?

Friedman: Oh, no. The game started out as D&D and it's moved through different systems at different points in our shared history. It began with 17 people at the American Society for 18th-Century Studies, so we set it at Strawberry Hill [an extravagant villa built in London by the politician Horace Walpole in 1749] because there's a bunch of digital material that's available. We have the entire inventory of the house. We have a floor plan of the house. Horace Walpole is the most amazing quest-giver ever. But, in order to not be precious about who would have known Horace Walpole or who would have been alive and how old would they have been, we treated it in a quasi-isekai way: these people have been brought together from any time in the long 18th century. So already, the anachronisms were inside the house. But there have been moments: I remember my players wanted to have a spa day in Wales, and the discussion of cheese became intense, detailed, and took up at least an hour. A hazard of the job is that we have so many digital tools and all of these players have access to them; we can't just go to London. We have to go to a specific street, to a specific house, right? And God help me if I haven't prepared. I may have threatened to make them all go to Brighton because they don't know enough about it—and it's a good 18th-century city for the uppity and the ambitious. It's really funny: a lot of our game group was in the UK for the Global Austen Conference, and I would get messages of people taking selfies at different sites that are now overlaid with the events of our game!

But, I think we are all primed to the idea that, like, the best Austen adaptation is Clueless, right? You don't have to go full Barry Lyndon and not have artificial light. Metropolitan is the other great Austen adaptation, which is not an adaptation of any one novel. What Whit Stillman is doing is thinking about Austen's writing process; it becomes Austen-flavored in a way that only someone who has spent a lot of time reading and thinking about Austen could possibly pull off, which is a lot more than a lot of modern Austen adaptations actually do. To be faithful to plot and not spirit—something's lost, right? So we as players are already primed to take certain liberties. My love of the period is enough to take some fuzziness along the way.

Thanks to Dr Friedman for her time!

Add a comment: