Guest Post: On OVER/UNDER, by Our Man In California

Ahoy!

You probably know what this newsletter is, since you signed up for it. But if you don’t, why not come by the Discord and ask someone? Perhaps Marsh or Jim will be around to say hello (or ahoy.)

SALE! SALE SALE!

Links!

OVER/UNDER: Through, by Mark Wallace.

SALE! SALE SALE!

This newsletter is getting surprisingly popular and, consequently, expensive to run. To make this easier, and for you to have a rewarding way to support us, we’ve put the all the paid-for zines on sale for the month! It’s (near enough) Christmas, after all.

For $13 (or you can buy them at half-price individually if you already own one or two!) you get:

TEETH: STRANGER & STRANGER, a grotesque, standalone, table-top, roleplaying mini-campaign for 3-6 people.

The players portray mutated bumpkins, battling to remain human while wandering a cursed corner of 18th-century England. Will they find what they need to save their village? Or will they return too changed to care?

TEETH: BLOOD COTILLION is a grotesque, single-session, standalone table-top roleplaying game for 3-6 people (including the GM).

It is set during a single night at a high-society ball, in a cursed corner of 18th-century England. The players are formidable assassins, disguised as husband-hunting ingenues, who must root out the occult evil that lurks in the manor, destroy it and, ideally, survive.

TEETH: MORE TEETH, which is a supplement to TEETH, a grotesque, table-top roleplaying game for 3-6 people (including the GM) set in a cursed corner of 18th-century England. This download does not contain the full ruleset or setting! Instead, it's a series of expansions and oddities that work with the main book.

SALE! SALE SALE! etc

Anyway, below there is a fantastic essay on the MMOLARPBPG event, OVER/UNDER, which took place recently in the depths of cyberspace. Our intrepid cyber-reporter Mark Wallace, of California, US, was on the scene.

Please read it, it’s really good.

But first, a couple of links:

LINKS!

New 18th century naval hero: Aristide Aubert du Petit-Thouars. And not just because of the name. “[He] was promoted to captain, commander of the Tonnant at the Battle of Aboukir Bay, where he died on 2 August 1798. During the battle, his men heavily battered HMS Majestic, inflicting casualties of 50 killed, including Captain George Blagdon Westcott, and 143 wounded. After having lost both legs and an arm, he continued to command from a bucket filled with wheat until he died.”

Why did they have buckets of wheat aboard? Was it for soaking up blood? If anyone knows the answer please reply in the comments or let us know on Discord.

Marsh and I appreciated this article on the right’s obsession with LotR and D&D. Horrifying, as ever, but insightful.

The American Library Association’s Platinum Play awards recognised a bunch of games, including Apocalypse World, Call of Cthulhu. TTRPGs beginning to appear in this sort of mainstream cultural observance is an interesting. Especially when it’s these particular TTRPGs. Forget ye not that Apocalypse World is kickstarting an new edition.

A prospective new Teeth HQ has been put in the market for just £2.8m. Probably need to sell a few zines to pay the mortgage on this, but that won’t stop us trying.

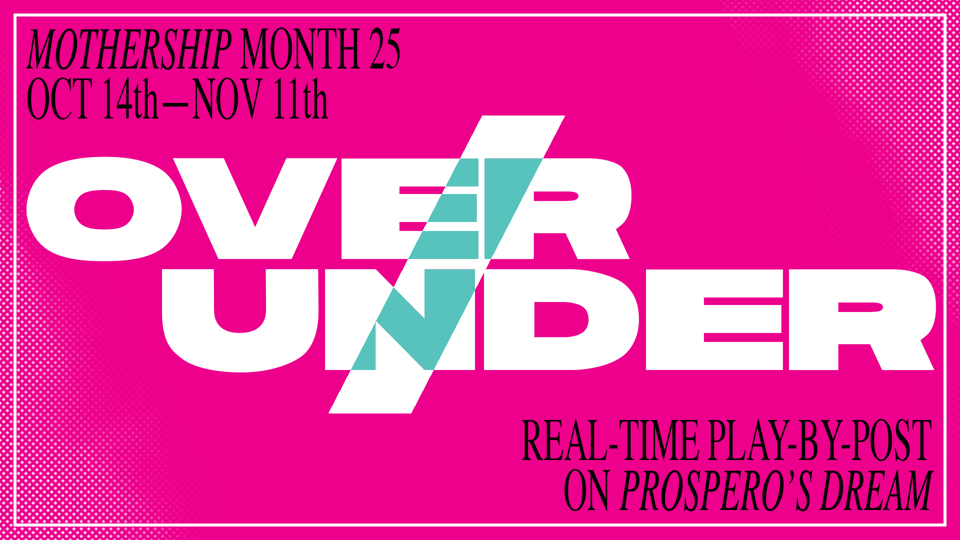

OVER/UNDER: Through

or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Dream

I have never been to summer camp. But I was absolutely one of those experiencing end-of-summer-camp vibes in the days following November 11, when the remarkable massively multiplayer online live-action roleplay-by-post game OVER/UNDER drew to a close.

If you are anywhere near the indie tabletop space, it's been hard to miss talk of this phenomenon, which ran for a month and drew something like 1,200 players into its orbit — the orbit of the space station Prospero's Dream, that is, which serves as the setting for a Mothership campaign of the same name and on which OVER/UNDER took place. The Dream is a massive, lawless platform, population 8 million, where a mafia syndicate, mercenary corp, religious cult, and teamster's union maintain a tense collaboration that controls the docks, bars, nightclubs, businesses, and life support systems of the station.

Don't forget to pay your oxygen tax, friend, or you'll wind up in the Choke — a place that deeply honors Mothership's genesis as a "sci-fi horror" roleplaying game. Stir in an elite hacker crew, a capitalist conglomerate, and some really fucking weird characters running the kind of slickware you don't want to meet in a darkened ductway, and you have a recipe for a deliciously terrifying space-station layer cake that wardens can use as everything from a waystation to a full campaign setting that would probably sustain you for quite some time.

OVER/UNDER's ruleset was cannibalized by Sam Sorensen from his play-by-post wargame Cataphracts, with a tasty icing of murder, infohacking, and commerce smeared on top. This sounds like all the ingredients for a tense, treacherous, danger-filled month of assassinations, deoxygenation deaths, anti-corpo shenanigans — even, dare we say, war. And all that did go on in OVER/UNDER. But judging from the many heartfelt and tearful post-mortems that have appeared since the game closed, none of it is what made O/U such a deeply felt and meaningful experience for so many people.

What made OVER/UNDER special was a combination of three things, each of which worked in ways the game's creators hadn't intended, to bring a new kind of life to the primordial MMOLARPBPG ooze.

THING 1: OVER/UNDER was always on.

Sorensen's play-by-post games take place in real time: order a Cataphracts army to march east for a week on Tuesday afternoon and they won't get there til the following Monday night. But Cataphracts is set in the 13th century; there's no in-fiction way to communicate with other commanders while you trudge across the tundra with your troops. In the anti-canon whenever of Mothership, however, on a space station with 8 million other poor souls, there's ample opportunity for interaction.

This made roleplaying matter, more even than in many roleplaying games. There's only so much character development you can do sitting around a table with friends for three or four hours a week while trying to survive the horrors of the abandoned capital ship you're exploring, or punching goblins or whatever. There's much more you can do when you can dip into your character 24 hours a day for an entire month, with no hit points or dice to slow you down.

No hit points or dice, you say? That bring us to...

THING 2: Most of the players had nothing to do.

This is not a fault or complaint; on the contrary, it was possibly the single most important thing about the experience.

Sorensen and Mothership creator Sean McCoy very wisely tapped a handful of game designers, module creators, actual play performers, and other deeply TTRPG people to play as the bosses of the six factions in the game. But that made them the only characters on the station with any real mechanical power or control; everyone else were Denizens, who could do little more than vote on whether they approved of their leadership. (Not an effective recipe for successful civil society, as we've learned.) A subsidiary thinget here is that OVER/UNDER drew many more players than its creators anticipated. The combination meant that there were more than 1,200 people ready to roll some dice, but only about 20 with anything resembling a character sheet. And even the faction bosses, because of the slow-fast real-time nature of Sorensen's game, weren't rolling dice all that often. So this writhing bolus of players did what they always do in this kind of scenario: they played their own game.

Almost immediately after the event kicked off, OVER/UNDER transformed itself from a wargame embellished with a bit of roleplay into a massive text-based LARP with the wargame operating in the background. More than a thousand people had a space to inhabit, and damned if they weren't going to bring it to life. Bars and bookstores sprang up, nightclubs opened, gardening clubs sprouted, charitable societies handed out credits to keep people out of the Choke, there were fight nights, dating services, a Mop Squad that would toss a bucket of notional water on the Denizen of your choosing (for a price), and so much more — all of it operating in a virtual economy with few game mechanics behind it where Denizens were happy to spend their credits on things that were, in "reality," no more than a bit of text typed on a screen.

I won't attempt to enumerate the many dark and/or delightful experiences and characters to be found around Prospero's Dream, but I will say this: The enormous volume of creative roleplaying energy pouring out of the Denizens took the wargame that was meant to be center stage and pushed it into the background. Crucially, though, it didn't do away with it altogether. What the unexpectedly large and creative populace did was turn the wargame into a kind of faction turn that worked in the background to give Denizens something to react to. There was still a game going on that affected factions' win conditions, but only about 2% of the players were playing it. Most of the people on the station were doing what people on lawless space stations normally do: going about their lives, leaning into what skills they had to earn enough to support their lifestyle, getting mixed up in lesbian romantic drama, and trying to stay out of the Choke.

This, I think, more than anything else, was the unintentional genius behind OVER/UNDER. Players knew the wargame was happening, most were part of a faction that was involved in it, and many were working toward their faction's goals. But because the overwhelming majority couldn't directly engage with it, what the game was "about" became something else. The wargame was just a necessary catalyst for the fascinating and beautiful community that often emerges when free-form play meets just the right measure of gameplay and narrative constraint. It's really hard to design for this. Sorensen and McCoy had the good fortune to have it just happen on Prospero's Dream.

But about that other thing...

THING 3: Social technology has come a long way.

I have never been to summer camp, it's true. But I have been to Second Life. I have been to Eve Online. I have been to EverQuest and World of Warcraft and The Sims Online and I have poked my head into Achaea and a number of other text-based gaming environments. I wrote a book about the kinds of communities and interactions that emerge from places like these, and while my first reaction was that OVER/UNDER had simply reinvented the MUD, I want to say that Prospero's Dream was different. Not because it had better game mechanics or better moderation or better worldbuilding — on all these scores it was impressive, but really no more so than any other. It was different because we're different. It was different because we've learned a lot over the last two or three decades about how to behave in online spaces, and how to police them.

When Julian Dibbell wrote A Rape in Cyberspace, more than thirty years ago, online culture was still very young. By the time I was writing about virtual worlds, ten years later, griefing had been honed to a fine art. Twenty years after that, its fallout has become deadly, according to some.

But something else has happened in that time, which is that tools for mitigating and de-escalating interactions online and off have evolved. I'm not talking about things like fine-grained social media settings or Bluesky's block lists. I'm talking about things like content warnings, techniques for calling people in, new ways to understand marginalization and the always imperfect task of allyship. I'm talking about checking in and care and compassion and humility and the universe of things that were dubbed "political correctness" in the 1980s in a very intentional and derogatory way, but which are actually the very things we need more of in a society in which polarization has become an aim in itself with no thought of principle or safety or reason — but I digress...

All this is not to say OVER/UNDER wasn't without its problems. The mods did have to kick a few people, and a few tough conversations needed to be had. But I'm convinced that one of the reasons O/U worked so well was that we've learned a lot in the last twenty years about how to behave in what I'll call characterful spaces.

In OVER/UNDER, you could see this in the out-of-character chat that punctuated conversation almost wherever you went. If a fight was started in Marlowe's Rest (the bar that was taken over by my faction, the cowboy hackers of the CanyonHeavy Collective), you could be sure that before the first punch was thrown there'd be someone checking in via double brackets, saying something like, ((Let me know if I shouldn't knock your block off. Happy to lose this one if it's better for you.)) In professional wrestling, this kind of kayfabe is an unspoken pact between performers and audience to take this pretended smackdown as "real." In OVER/UNDER, where performers and audience were one, it became a tool to guide roleplay, and helped underpin the fact that what we were doing was playing pretend. That didn't make the interactions any less meaningful, nor does it stanch the bleed. But it helps keep everyone on the same page, with an awareness of when things might be straying outside someone's comfort zone, and helps avoid the kinds of harms that can too easily arise without these kinds of tools.

None of this is really new, of course, but it wasn't the norm twenty years ago. And while OVER/UNDER's creators never anticipated the kind of community that would form in their game, they did a great job of managing it. The story of the Chokespawn incursion is one I'd love to dive into — if Marsh and Jim weren't already giving me way too many words here — but I'll just say that Sorensen, McCoy, and co. did an outstanding job of recognizing when a bit of roleplaying was having unintended and somewhat traumatic consequences, and of managing the community through it without being punitive or vengeful.

I'll leave you with this: OVER/UNDER was a very cool experience. Part of what made it so cherished, I think, is that it hit at a time when a lot of people are craving connection and community. Its world came alive in part because it was managed well, and in part because of its unmanageability — you could never know all of what was going on there. It had bosses, but they weren't the real story. The real story was the people, and the way they treated each other. It might have been set on an overcrowded orbital platform ruled by oligarchs and drug dealers and crime syndicates and hamstrung trade unions, but its players understood that losing isn't to be feared when people know how to take care of each other and there's enough to go around. They celebrated their differences and they had fun.

And in the game.

==

Thanks, Mark! More soon.

Add a comment: