A Hard-Bitten Cop And Some Game Rulings That Changed Me Forever

Welcome to the TEETH newsletter! This is a (mostly) weekly transmission about our adventures in the very secret land of Tabletop Roleplaying-Games. We have published a whole series of our own TTRPGs! That series is expanding. In this regular publication we also look at other RPGs, play stuff, interview people. It’s a whole lot of newsletter.

What’s within is written and compiled by dastardly swine, Jim Rossignol, and bristling mutton-chop, Marsh Davies. Come and join us over on the TEETH Discord! Free tooth emojis for everyone.

And hey, if you can wish to support us and also get a fantastic 320-page RPG, you can BUY OUR BOOK. If you aren’t already a member of that rather cool and highly exclusive club. There’s a whole range of TEETH RPGs to go along with that.

Hello, you.

Links!

Feng Shui

Hello, you.

We had to skip our update last week due to the sheer weight of work stuff. Jim’s day-job pressed heavily with deadlines, and Marsh has been non-literally buried beneath preparation for a GOLD TEETH crowd-funder. (Our forthcoming occult pirate book!) It’s looking amazing, and we are both very excited.

Marsh says: I've made a small update to the Teeth PDF to introduce Bookmarks! You can now find a pop-out menu in PDF readers with links to help you navigate the book. Full credit goes to Snowkeep from our Discord community for letting me know this was even possible. You can find these on itch.io.

And newsletterwise we’re back this week with our usual fare, including an over-egged account of a pivotal (for Jim) session of 1996 action RPG, Feng Shui. We hope you find it stimulating.

And as always, we appreciate your support. If you fancy or chat, or just want to lurk, then please come and join us over on the Teeth Discord! There’s some games being organised in the LFG channel. Come and play with our community!

Love,

Marsh & Jim

LINKS

THING OF THE WEEK: Look, I know I keep banging on about this, but between Wyrd Science and Quinns Quest we are blessed with some superb TTRPG media right now, and I don’t want them to go away. Wyrd Science 6 is just as good as the other issues. I read it cover to cover and nearly dropped it in the bath.

This exhaustive influence map for Blades In The Dark is an astonishing labour of love. Here’s a link to the full-resolution image, as it doesn’t seem to neatly resolve from the original link for some reason.

A terrifying journalling RPG by one of our Discord members: “You’re on-call for a tech company. You keep getting alerts, and everything feels like it's on fire.”

I am sure everyone has seen Deborah Ann Woll teaching The Punisher about D&D, but just in case. See how she manipulates his expectations about dice rolls to open him up to a lifetime of railroading by the DM? I’m only teasing, it’s just as heartfelt and beautiful as everyone says.

Vampire Cruise looks incredible. “Vampire Cruise is a 40 page ttrpg adventure zine, ready to play with any rules-light osr style system. It includes maps, lots of vampires, a mummy cult, and room service.”

A DIGITAL GAME (OF THE WEEK): “It’s time to start your very own medieval manuscript workshop” is one hell of a pitch. Scriptorum: Master Of Manuscripts actually delivers on that, too. An illuminating piece of work. (Eh? Still got it.)

Feng Shui: A Hard-Bitten Cop And Some Game Rulings That Changed Me Forever

For this newsletter I had planned to write about setting-agnostic rule systems, system-agnostic settings, and the way in which we sometimes hack one game to work with another title’s adventures. I admit that some of the reason for this was that I really like saying the word agnostic. What a beaut! Agnostic. I relish it. This proposed essay, if I ever write it, and let’s assume that I already have, links to something about vibes in dice rolls in a later newsletter, building up a sort of coherent commentary on RPGs as sampled and adapted literature and the quilts of meaning that we build out of related cultural materials.

As you can see, great stuff is already happening in my imagined future.

But in the present something more important arrived from the past: I remembered a game of Feng Shui.

It’s unusual that single sessions of RPGs resonate throughout the years, but some do, and they matter like punctuation. A few of the things this one off evening taught me ended up shaping my thinking for years, although some of those things aren’t actually from Feng Shui at all.

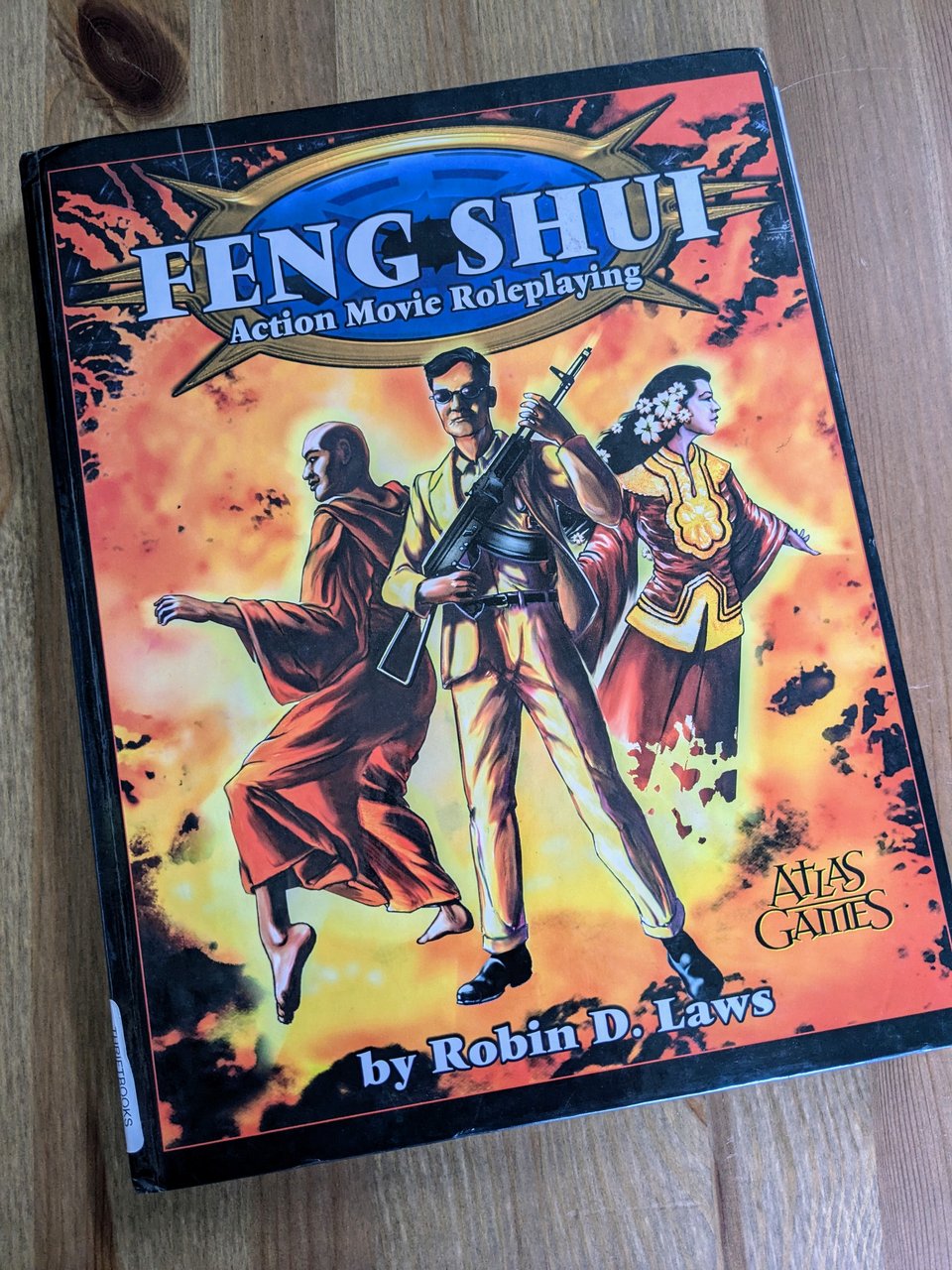

Feng Shui by Robin D. Laws is a game of action movie tropes. It leans on low-budget Kung Fu movies for many of its core principles and aesthetics. As such the character archetypes are tropes like Scrappy Kid, Martial Artist, Cyborg, or Maverick Cop. If you’ve watched a good cross section of 80s movies or pastiches thereof, then you are already familiar with the genre. It provides rules to match.

The game was chosen by my long-standing colleague in nerdy exploits, Kieron Gillen, who was subsequently the author of smash-hit ultra-meta RPG, DIE. He was the GM for that game and had previously been enjoying a brief campaign of D&D along with myself and a number of folk working on games magazines at that time (around 2002). We had been glad to be wizards, dwarves and so forth for some evenings of adventure, but unfortunately the nervously erratic DM of those sessions had decided that all the characters had died in their sleep, and abruptly informed us of this decision via email. As an antidote to both this arbitrary ending and to D&D as a whole, Gillen volunteered to run Feng Shui. He would, in doing so, provide another arbitrary ending of his own, albeit one of a rather different sort of register.

I have a second-hand copy of the 1999 printing of Feng Shui right here on my shelf, complete with someone else’s Shadowrun character sheets folded into the back. An envelope of pure ‘90s. I have barely read this book, and, tragically, never brought it to the table. Nevertheless, glimpsing its time-creased spine often reminds me of that long-ago session and the fact that it changed me in three distinct ways, none of which really have all that much to do with the book itself, but all of which thank Robin D. Laws’ creation for their existence.

Firstly: I understood, for the first time, that one-shot adventures were a valid form of TTRPG.

While I had played the odd single session before, most notably my first ever game of D&D run by my older cousin Steve, these always felt like campaigns that were cut unduly short. These games were, to my youthful mind, meant to be played over weeks: extended stories with arcs, beats, and villains to be eventually defeated. Why, it was all there in the XP progression systems and endless source material! A one-off might be theoretically possible, went my thinking, but it was not meant to be that way.

Here though, it was not simply a one-shot, it was a one shot that had to -- by the rules Gillen had set out -- end on a nail-biting crescendo that would never be resolved. It couldn’t go any further. And so after a bar-brawl and an ascent through a heavily-armed corporate HQ, the final scene was a melee with a blue-flame-wielding wizard that ended with us being thrown, locked in close combat, through the top floor of a skyscraper. There we froze, stopped mid-plummet towards the concrete and massed cops below.

“The End,” explained Gillen. There our glorious crew would stay, guns akimbo, forever. “We have to end on a cliffhanger,” Gillen clarified. That was the rule. (It wasn’t really, but he always had a knack for indulging this sort of drama.)

More importantly, with this conceit, my teenage preconceptions evaporated. TTRPGs were a single evening’s entertainment, and have been ever since. To this day I like a one-shot. I run them regularly. I even helped write one or two. Yet I still encounter people who imagine to play an RPG is to commit to three months of evenings, as if the grand campaign were the only fruit available. Not everyone had their moment. Not yet.

Which brings me to the second thing that this Feng Shui game did for me.

Due to my age at that time and my professional anxiety as a kid who was starting out around people who were more talented, more experienced, and far hungrier for success than I was, I was desperate to be original. I worried constantly about how and when to employ stereotypes, tropes, and the like. I would studiously avoid them, I concluded. Writing advice confirmed this. I adopted both an intellectual snobbishness and a humorous distancing (common to the unconfident) as I devoured modernist novels and genre-breakers as a sort of intellectual prophylactic against a lack of originality.

Feng Shui meanwhile, leaned into the tropes. It recombined stupid shit. It was absolutely rich with the foolish energy of the movies it traded upon. The game we played, that single session, somewhere between City On Fire and Big Trouble In Little China, made me end up thinking for years afterwards about the tropes and stereotypes it relied upon to work. Suddenly, youthful Jim Rossignol was concerned with iconic resonance: the meaning of big archetypes in fiction and why they are so useful and so prevalent. A single evening’s entertainment in Ross Atherton’s one-bedroom flat on the London road made me accept that these things are there for us to make our own, like the words in an existing language. Ready-made blocks are available as we build our stories. There’s no need to invent new ones, although that’s fine too. The real challenge is to rearrange the existing meanings into something that belongs to us. Ownership is critical to identity. You can be a barbarian, or a wizard, or a maverick cop, but one that you have to make your own, with your personal meanings and imagery draped across them like tapestry cut from the necromancer’s palace wall.

To this end, Dave Taurus, enthusiastically over-stubbled karaoke-enjoyer of the EDGE magazine team, played the hard-bitten cop. “I don’t care,” he drawled, feeling out a possible catchphrase in his not-quite-successful impression of a New York accent. He threw down the imaginary butt of a cigarette and glowered ostentatiously as he did so. It was impossible not to imagine the gold rings, the St Christopher, and the dirty linen suit. It was very stupid, and it was hilarious.

I can’t remember anything about my character, other than I could shoot a force beam from my forehead, a long-term real life goal made palpable, if just for a moment. But many games contain these magicks. It was how everyone leaned into their archetypes that I remember. I stopped shying away from genre conventions. I suddenly understood, far better than I ever had before, why they were the starting point.

Which brings me to the aspect of this game which did the most to explode my youthful preconceptions and turn a tide set in motion by years of running traditional RPGs. Gillen’s breakdown of the rules of Feng Shui were a point of transformation for young Jim Rossignol -- Gillen does not recollect any of this, I should stress -- when our similarly youthful GM announced that the more ludicrous a thing our character attempted was, the more likely it was to succeed.

To be clear, this is not exactly how the written rules of Feng Shui put things (I had to check). But it was, I forever remembered, how Gillen, as aware of how to unlock people’s imaginative engagement then as now, sold it to the group. Naturally this rule was also an unexpected reversal of how I understood an RPG to work. It made a mechanical primacy for narrative in a way that was so simple, and so complete, that it changed me and was carried in my head always thereafter.

Fen Shui, as you might expect, it’s in fact an action game where the more complex and unlikely the action, the harder it is to achieve. There’s a table of examples along these lines in the early pages of the book. But this declared rule of ludicrousness was, whether by whimsical fiat of Gillen or misrememberance or misunderstanding of my own invention, a point at which I suddenly realised that RPGs did not have to be about the rules “getting in the way”, as I had always instinctively understood them.

I had long found RPG rule systems to be limiting, frustrating, or rigid, in a way that opposed (to my thinking) the significant simulations of a miniatures game. This was partially the fault of the kind of systems I’d played, of course, but back in the ancient times there was also a paucity of choice. As a teenager I habitually discarded written rules to create something that, in retrospect, was far closer to the “rules lite” stuff we play today, because I really just wanted the guy in the robot armour to fight the wizard, whatever the rules said about their relative power differences.

Suddenly, in Gillen’s Feng Shui session, I was up against a situation where, if I said “I shoot the guy,” my character would almost certainly miss. But if I said that they slid along a bartop blasting up bottles of vodka as improvised mid air incendiary devices, and then lit a half-chewed cigar on the smouldering corpses of my enemies, well, then that was almost certainly going to happen as described.

Rules, at this moment of transformation, did not have to be limiters on the characters powers or ambitions, but rather multipliers of absurdity. The things players said did not have to be “realistic”, whatever that meant in the context of pulp fiction. In fact, they could not be. We had to engage with the fiction hyperbolically, or fail. That there should be a direct, inverse mapping between the floridity of a player’s descriptions, and the actual difficulty of pulling that thing off is probably something an RPG somewhere actually does, but I can tell you that encountering it in the wild, inexperienced and unexpected, like this, was an explosion. Rules as permission. Rules as accelerant. Rules as bait and hyperbole.

I think about it all the time. I think about it as I run RPGs and design systems for digital games. Misremembered, invented, or misapplied, it’s been a life lesson.

As things turned out, that game of Feng Shui was the last time I would play a TTRPG for over a decade. I had learned a lot, but it seemed like I was done with RPGs until I finally returned to run two parallel D&D campaigns in my mid 30s. And when I did that, picking up the old rules, there was an itch. An itch left by an evil wizard, wreathed in blue-flame, falling amid shards of shattered mirror glass from the side of a skyscraper.

Perhaps in another twenty years I’ll write a recollection of what happened next.

More soon! x

Add a comment: