no accounting for taste (except through voluminous historical research.)

There’s still time to enter the giveaway for three paperback copies of Anne LeBlanc’s super fun, delightfully inventive cheese heist novella, The Transitive Properties of Cheese! Fill out the form HERE.

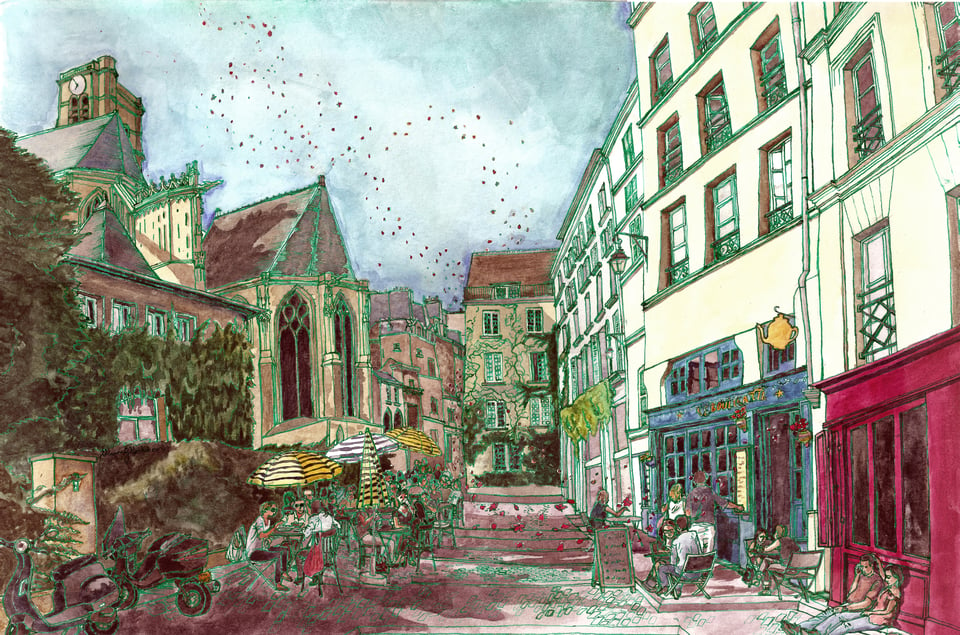

The plan for the next Regency cheesemakers book is to set it in Paris (!); in the Marais (a quarter on the Right Bank which has preserved many gorgeous medieval buildings) (!!); in a restaurant (!!!). This choice is based fully on self-indulgent longing for a city that I love but have not been able to visit for nearly a decade. From 2010 to 2016 I had both the great good luck and poor financial planning to pass through Paris at least once a year.

But, because I was 1. poor 2. socially anxious, I did not immerse myself in the food culture at that time. My go-to move was to buy a baguette and some brie and eat them in a park.

So now I find myself immersed in research. I talked a bit in my last newsletter about what I’ve learned about the landscape of the French Caribbean colonies in the decades just preceding the setting of the book. Colonial slave economies and cultural food preferences are inexorably linked, of course; Susan Pinkard (in her book A Revolution in Taste: The Rise of French Cuisine, which I just finished reading and will thus be referencing extensively in this newsletter) mentions in passing that between 1700 and 1800, the period when Barbados and Jamaica became huge exporters of sugarcane farmed by enslaved peoples, the average person in England went from consuming less than a pound of sugar a year to consuming eighteen pounds of sugar a year. This sweet tooth remained characteristic of the English for the next two hundred years, wartime rationing nonwithstanding.

The French, though they engaged in colonial exploitation on an equally grand scale as the British, have generally expressed a different set of cultural values through their cooking. Pinkard is extremely concerned with the modes of thinking which led to each subsequent movement in French food, from Galen’s notions of balancing the four humors — which dictated the “balancing” regimes promoted by medieval doctors — down through Rousseau’s fervent promotion of vegetarianism and loathing for spices. But the idea which comes through in the mid-17th century, when the French finally and definitively put away medieval modes of cooking, is one of authenticity — ingredients should taste like what they are, instead of being disguised or “corrected” by heavily spiced, sugared, or vinegared sauces. (For comparison, consider the modern proponents of locally-sourced heritage breeds of chicken raised on a natural diet vs. those us who lovingly submerge our air-fried chicken nuggets in a flood of barbecue sauce.)

But around 1650, these sauces started being discarded in favor of those made from the concentrated essence of the food at hand, such as bouillon, jus, and coulis, each varying in consistency depending on how much of the solids of the principle ingredient were incorporated. But cooks such as Massialot (who published his most famous work in 1705) also promoted a wide variety of fat-based and emulsified sauces, such as flour-based roux, the yolky predecessors of hollandaise and mayonnaise, and cream and butter sauces, which also worked to highlight the flavors of the primary ingredients of a dish. In the run-up to the Revolution, the French became ever more worried about what, exactly, what a food “authentic,” leading some to espouse a “peasant’s diet” of fresh veg, fruit, and cheese (something very few French peasants at the time could have afforded, but literal truth is not necessarily the province of philosophers.)

It’s fascinating to compare these notions of what makes cooking good and noble to the last book on food culture I read, Invitation to a Banquet by Fuschia Dunlop, which examines (and extols) Chinese regional cuisines. Dunlop focuses on what separates Chinese food as a whole from western cuisine, but I was rather struck by the similarities. Chinese scholars have also long espoused a “simple peasant diet” (spoiler, this means even more veggies), and Chinese haute cuisine is as intense about perfectly in-season veggies and fruits as the French, and has been for roughly a thousand years longer. (It may not be completely fair to compare the vast number of different vegetables eaten in China to the rather paltry numbers eaten in France, given the relative latitudes of both. In any case, Pinkard gives a short list of 15 recommended by a late medieval manuscript on household management from Paris. Dunlop describes the hothouses the Han dynasty used to grow fruits and vegetables out of season 1500 years before that, including a vast array of tubers, greens, and aliums.)

Interestingly, both traditions are also fanatical about crafting slow-simmered stocks which concentrate the essence of their ingredients. I found extremely similar recipes in these two books for preparing a Chinese duck stock and a French chicken jus, which consisted of sealing the bird in a clay pot or casserole and then simmering it over a barely-there fire for many hours, until it created its own, extremely-concentrated broth.

Dunlop also makes the point that the idea of a sit-down restaurant, if not the specific incarnation which came to be iconic of French culture, is an old and not especially European one; the Song dynasty capitals of Bianliang (now Kaifeng) and Hangzhou both had thriving restaurant scenes in the 11th century, which even featured different regional cuisines from around China. The French version, with its mirrors and gilt fittings, was modeled after the coffeeshops which came to be all the rage in Paris after an Armenian merchant opened one near the Saint-Germain-des-Prés in the 1670s. Initially French “restaurants” served the “restoring” health food of the time — that is, tiny porcelain cups of clear, easy-to-digest bouillons. (I am glossing over a whole theory of dietitics here because I found it annoying to read about and think you might as well.) These establishments also offered such “simple” fare as “porridge, rice pudding, semolina, eggs, fresh fruits, preserves, butter, and delicate cream cheeses” (from Pinkard.)

Perhaps inevitably, this light fare gave way to the style of restaurant we are more accustomed to, with dozens of dishes available in a variety of rich sauces and preparations. An English visitor to Beauvilliers’ restaurant (located in the Palais Royal) in 1802 described the menu thusly:

Soups, thirteen sorts. — Hors-d’oeuvres, twenty-two species. — Beef, dressed in eleven different ways. — Pastry, containing fish, flesh and fowl, in eleven shapes. Poultry and game, under thirty-two various forms. — Veal, amplified into twenty-two distinct articles. — Mutton, confined to seventeen only. — Fish, twenty-three varieties. — Roast meat, game, and poultry, of fifteen kinds. — Entremets, or side-dishes, to the number of forty-one articles. — Desert, thirty-nine. — Wines, including those of the liqueur kind, of fifty-two denominations, besides ale and porter. — Liqueurs, twelve species, together with coffee and ices.

Now, as for the specific mechanisms of the restaurants of the age: I am hoping that the book I have just started reading, The Invention of the Restaurant by Rebecca Spang, will cast some light on the issue. I am still meditating on whether I should roast a few chickens according to the classic methods described by Pinkard as research.

As always, I hope you are keeping safe and staying hopeful in these trying times,

Sharon

P.S. There’s a lot of pretty horrible stuff happening in the U.S. right now. I suggest you pick one thing you can do to serve your community tomorrow — call your senators about protecting reproductive healthcare, immigrants, or the rights of queer people, donate money to a food bank, get an overdue vaccination — and do it.

Add a comment: