Storm in Hanoi

In mid-June, crisis struck a little-known telco company headquartered in Tampa, Florida. Syniverse connects mobile operator networks and handles global roaming for all the big American telcos (ATT, Verizon etc), helping traveling devices find and latch onto local cellular networks. When a dumpster fire of a glitch took down Syniverse’s network, roaming services were disabled for tens of millions of people across the world – including me, in Hanoi, on a fairly vital assignment.

I first noticed my phone was acting up after a surreptitious meeting with some diplomats and I’d sincerely worried for a few hours I’d been hacked. I was a week into Vietnam at that point, irritated with my handlers and on edge after hearing about the arrest of someone I knew. The hacks I would have met to blow off steam were all in Europe for summer vacation and I didn’t want to risk meeting locals so I’d spent much of the week in my own head, getting progressively paranoid. Worst of all, the people in government who I needed desperately to talk to were dodging me. This was entirely expected but frustrating.

When I got back to my 4th floor walk-up, a guy on our IT desk in D.C. accustomed to my hysterical email subject lines (“Laptop WONT start. On deadline!!) slacked me a Syniverse press release accompanied by the shrug emoji. Something had happened with a “peering partner … causing the global network to become flooded with error messages and causing a near infinite loop called a signaling storm.” A technical failure! I relaxed into my couch. The universe wasn’t being malicious, just clumsy.

Now blithely hooked up to WiFi, I checked my email to find five emails from the Vietnamese government. A missive had come from above. The people I needed to see – some of them, at least – would meet me the next day. I have a bad habit of facetiously playacting a religious person when good things happen to me but I swear I genuinely felt in that moment that God was good. God being, in this case, some number of men in the folds of the politburo, working away in mysterious ways.

In any case, I was set for my big meetings starting at 9AM. I got up early, went for a run, took too long in the shower and realized I had to hurry out the door. Still no data thanks to Syniverse so I punched in the destination in Grab while in my apartment and waited there until the motorcycle was downstairs. After minorly staining my pants with Banh Mi juice, I was off at 8:33AM.

I adore Hanoi. Like all my favorite cities, it wears its history plainly. It has the benefit of many lakes (Hà Nội as in 河內, "inside the rivers”) and a good number of neoclassical buildings not destroyed by B-52 bombers. On this trip, I spent a lot of the time I had on bikes looking out for images from a book I’d been reading for book club: “Chinatown” by Vietnamese writer Thuan. It’s a strange, strenuous text (not a single paragraph break!) that recounts the life of its central narrator through four cities: Saigon, Leningrad, Hanoi and Paris. What I loved most about the book was how closely it tied the narrator’s personal drama to the political tides of her time, showing how the two are not – are never – disassociated. The narrator almost reflexively lists the names of streets and restaurants, and references the news of the day. The effect is a story that captures not just in abstract but in delicious and tangible detail the rise of the USSR, the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin wall, 改革开放 etc etc. Par exemple: “Last year in Beijing Chairman Jiang Ze Min himself inaugurated the international mathematics festival.” There were so many references for me to look out for in Hanoi, which is why it was only around 8:54AM that fateful morning that I realized I was headed in the entirely wrong direction.

I knew the Ministry was somewhere in the French quarter, near the Opera House, so it was unusual we were ascending a highway. I clicked Google Maps to check but the satellites couldn’t locate me because — no data. The bike suddenly felt unreasonably fast. Every second I wasn’t doing something to make it turn around, I was pulling further away from where I needed to be. And Jesus Christ, I needed to be at the Ministry. I’d spent all week begging for this meeting. I had to text my handler and get him to stall. But: No. Fucking. Data. An infinite loop of error messages hovering in the ether. My impotence felt like a well opening beneath me. At the same time, however, I sensed this other thing creeping to meet the panic. It was going to be OK.

There’s a theory I’ve developed with Rach that to do this job, you must have the ability at certain points to be a bit stupid. You need to be reckless enough to take risks, which is obvious. But you also need, in the face of very little evidence, to be able to trust that everything will work out. Maybe I sound cavalier about this but I’m not. Willfully giving up control, closing your eyes, and fully expecting the best is sometimes – often – the only way to get through it. Hurtling through dark country roads with armed men you don’t know? Encircled by hostile ships on a rickety boat? Give a big smile and activate your stupidity. It’ll get you through and maybe get you there. Almost nothing else will.

Sweating under my helmet, I jabbed the driver to pull over. We skipped one… two… three… coffeeshops before he screeched to a stop in front of a pharmacy. Without me saying anything, the receptionist took my phone and logged me online. I clicked the chat with my handler and saw he had already texted me. “So very sorry, Madam.” The meeting had been delayed 20 minutes because the official was stuck elsewhere. I typed the address into Grab, in Vietnamese this time, and arrived with a minute to spare. I hopped off, fixed my hair, and by the end of the next minute, was seated on a wood lacquered chair in a carpeted room, sipping lotus tea.

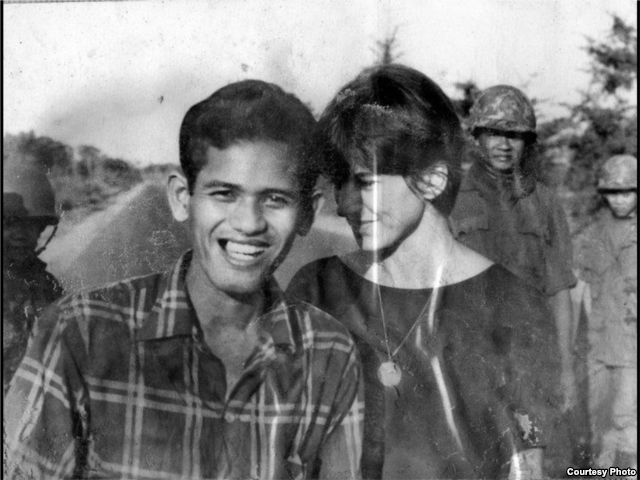

In April 1971, the Australian war reporter Kate Webb was traveling down Highway 4 in Cambodia when she was captured by Vietnamese troops fighting the Khmer Armed Forces, which were aligned with the U.S. There wasn’t a physical U.S. presence in Cambodia at this time, meaning that unlike in Vietnam, where military embeds were the norm, reporters were largely on their own covering Cambodia. This made it an exponentially deadlier assignment so when the body of a white woman was found in mid-April, newspapers across the world, including the New York Times, printed that Webb was dead.

Except she wasn’t. Webb at that moment was being marched through the jungles of eastern Cambodian with the war photographer Toshiichi Suzuki. She was emaciated, mauled with sores and using parachute silk as a menstruating pad – but she was not dead.

She kept placing one foot in front of the other, propelled by the memory of an orange. She focused on it obsessively: “Bite into it, and the sweet juice runs down your throat. Make a little hole in it, and the juice squirts out.”

In the story of this 23-day ordeal, recounted in Elizabeth Becker’s moving book on women who covered the Vietnam war, one detail is especially striking. To avoid sinking into a depression while in custody, Suzuki offered to teach Webb a traditional Japanese tea ceremony.

With delicate precision, they practiced the tea ceremony every day, using sticks and stones to pretend to pour water, whisk the tea, and serve each other. Webb imagined herself in a kimono. The ritual allowed them to concentrate on art, forget their deprivation, calm their nerves, and keep their sanity.

I try to think about this. In the eye of a storm, there’s value in a level of myopia. Even in petulant, entitled stupidity. Trust with vigorous conviction everything will be OK. What’s the alternative?

This email was written to the sounds of Bobby and Ruairí snoring through a Sunday daytime nap in preparation for the Euro finals early tomorrow morning, and occasionally, to Omar Apollo’s new album, especially the ending track, “Glow.”

(“Chinatown” by Thuan and “You Don’t Belong Here” by Elizabeth Becker — both in stock at NLB)

P/S: I’ll be in Taiwan for most of August. Please send recommendations <3

Your friend,

Reb