From a great height

Welcome one and all to what I know is going to be but the first of many reflections I have in my lifetime on the work of writer W.G. Sebald. To pre-existing Sebald fans… I am down bad. To the unacquainted, let me offer an enthusiastic introduction.

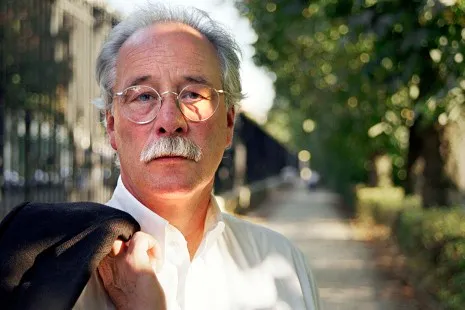

Winfried Georg Sebald (1944-2001) was a German writer and academic. He was born into wartime Germany, studied in Switzerland, then eventually became a lecturer at the University of East Anglia on the eastern coast of England, where he settled, lived and wrote for three decades before being killed in a head-on car crash at the age of 57.

In describing Sebald, both seasoned critics and Reddit reviewers highlight three things: His preoccupation with memory; his “strange,” “unorthodox” use of images within his books; and his position as a writer “straddling” fact and fiction. Sebald wrote about real things in the past, but made up characters, scenes, dialogue. He didn’t do it in a traditionally novelistic way but in a way so peculiar to himself scholars only know how to call it “Sebaldian.”

An example. In the Rings of Saturn (1995), one of the topics Sebald investigates at length and weaves into the central narrative (a long stroll through Suffolk County) is the migration of silk cultivation from China to Europe. Read with me the first Sebaldian extract I ever drew my pen through agitatedly, paying particular attention to that last, run-on line:

“The Dowager Empress had a daily blood sacrifice offered in her temple to the gods of silk, at the hour when the evening star rose, lest the silkworms want for fresh green leaves. Of all living creatures, these curious insects alone aroused a strong affection in her... Every day that came, Tz’u-his walked the airy halls with the ladies of her retinue, clad in white pinafores, to inspect the progress of the work, and when night fell she particularly liked to sit all alone amidst the frames, listening to the low, even, deeply soothing sound of the countless silkworms consuming the new mulberry foliage. These pale almost transparent creatures, which would presently give their lives for the fine thread they were spinning, she saw as her true loyal followers. To her they seemed the ideal subjects, diligent in service, ready to die, capable of multiplying vastly within a short span of time, and fixed on their one sole preordained aim, wholly unlike human beings, on whom there was basically no relying, neither on the nameless masses in the empire not on those who constituted the inmost circle about her and who, she suspected, might go over at any time to the side of the second child Emperor she had installed.”

(Tz’u-his is, of course, the European phonetic spelling for Cixi, 慈禧)

Even re-reading this passage now, I feel a bit like I have been thrown onto the floor. Part of the craft here is the painstaking detail used to create the reader’s vision of place – “evening star”; “airy halls”; “mulberry foliage” – and this skill with environs is, for me, Sebald’s biggest magic trick. He deals in memory, using inherently fragmentary detritus to produce this ghostly, shimmering prose that feels like remembering or yearning or dreaming – like the experience of it.

More Rings of Saturn:

“As I sat there in Southwold overlooking the German Ocean, I sensed quite clearly the earth's slow turning into the dark. The huntsmen are up in America, wrote Thomas Browne in the Garden of Cyrus and they are already past their first sleep in Persia. The shadow of the night is drawn like a black veil across the earth, and since almost all creatures, from one meridian to the next, lie down after the sun has set, so, he continues, one might, in following the setting sun, see on our globe nothing but prone bodies, row upon row, as if leveled by the scythe of Saturn – an endless graveyard for a humanity struck by falling sickness.”

Another, from The Emigrants (1992)

“Now in the hills at Delphi, the night already very cool. We lay down to sleep two hours ago, wrapped in our coats. Our saddles serve as pillows. The horses stand heads bowed beneath the laurel tree, the leaves of which rustle softly like tiny sheets of metal. Above us the Milky Way (where the Gods pass, says Cosmo), so resplendent that I can write this by its light. If I look straight up I can see the Swan and Cassiopeia. They are the same stars I saw above the Alps as a child and later above the Japanese house in its lake, above the Pacific, and out over Long Island Sound. I can scarcely believe I am the same person, and in Greece. But now and then the fragrance of juniper wafts across to us, so it is surely so.”

For a while after reading Emigrants, it was difficult for me to walk through cool night air anywhere without recalling vaguely that last line – “… now and then the fragrance of juniper wafts across to us, so it is surely so” — and instinctively sniffing to see if I could smell anything in the wind.

When I picked up Rings at a Waterstones in Cork last Christmas, I had known nothing about Sebald. The cashier, who had long hair and a skater vibe, quipped “A classic!” as he bagged it, which I noted in my mental TBR. Since then, I’ve had the gratifying experience of learning of Sebald’s role in the work of many of my other favorite writers.

Scrolling on a Reddit thread for Sebald fans, I read someone recommend Benjamin Labatut, at which point I literally jumped out of bed, went into my office, and flipped to the acknowledgments page of When You Cease (2021), finding, yes – Sebald’s name among the “authors I would like to thank.” Here is Labatut himself in a 2023 interview with Public Books:

FP: Your work has been compared frequently to W. G. Sebald’s, perhaps the most renowned postwar German author. There are multiple allusions to his work in When We Cease to Understand the World. What is useful for you in him and his books?

BL: I don’t think anyone, anywhere, writes like Sebald. I reread his books every year. His melancholy and humor, the density of information that they hold, the beauty of his prose—which has a deeply strange effect, somniferous and hallucinogenic, that prevents you from remembering everything you’ve read, no matter how much you try—make him a complete exception. His oeuvre is an unreachable monolith, a summit that exits our world. In my opinion, he’s the best writer of the 20th century.

Elsewhere, I’ve found the many observations that Teju Cole, Rachel Cusk, Jenny Erpenbeck “owe a debt” to Sebald.

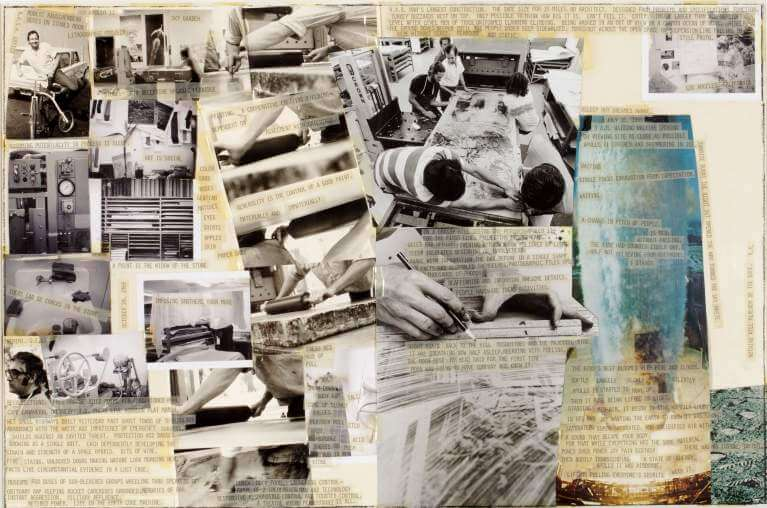

Sebald references a lot of art in his writing, notably Rembrandt, Turner and Auerbach. I’ve tried in vain to find connections between Sebald and Robert Rauschenberg, one of my favorite artists who also deals heavily in memory, though given they were coevals (R 19 years older than S) and given the German connection and their mutual interest in rescuing images from the past, it’s not implausible that they may have known of each other…

In 1997, Sebald visited New York for a few weeks to promote The Emigrants. Sadly, he came just three months before the Guggenheim opened a landmark Rauschenberg retrospective with over 400 of his works displayed, one of the biggest one-man shows ever at the time.

If I were one day to write a Sebaldian story, I’d bend history lightly, like he does, to have Sebald visit the show. I’d have him plod alone through Central Park on a gloomy winter morning. I’d have him start at the top of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic spiral and wander slowly down, thinking through what he thought of Rauschenberg’s messy, bleeding combines and what they evoked about something esoteric like the commercialization of plywood or the political history of the necktie. I would layer on my own memory of visiting the Guggenheim during the greenness of college, of attending the blockbuster show of my era (Hilma af Klint in 2019) and feeling, like Sebald once described memory — “as if one were looking down on the earth from a great height, from one of those towers whose tops are lost to the clouds.”

This is all possible in my imagination, enriched continuously now — and for the rest of my life — by Sebald.

***

P/S: I have realized it was disingenuous for me to have written in the past that xx email was “written" to the music of xx. Because in reality, I am physically writing either in complete silence or to “Brown Noise” on Spotify. So this email was, er, thought about to the music of John Coltrane and the single most nostalgic/yearning song on radio right now — party 4 u.