As if one is already free

Hello from a bright fall day in Baltimore,

I’m sitting in a café near Fells Point, at a table overlooking the harbor, with a cup of “London Fog” and the debris of a lox bagel. This is my afternoon station, in between a news conference and an appointment with a woman whose son might, depending on legislators, have a shot at parole after 34 years in prison. He was 16 when he killed a man.

I’ve had trouble recently trying to describe how things are. Rachel C. came back from Nairobi this week and I got to hug her; we found out today that the Post’s newsroom finance manager died from cancer; Julia’s visiting this weekend for Halloween; I’m going to New Mexico in November; and we’ve booked our VTL tickets for February. I do realize this is just a list of comings and goings. It’s almost as if – surprise, surprise – I’m having a little trouble settling down after the summer.

Lucky for me, there are always museums.

Ruairi and I went to the NGA on my birthday and stopped to take an elevator somewhere in the East Building. There was an artwork near the lift lobby – you know the type: pretty but not priceless, there to fill the space, there to provide relief for audio-guide masterpieces – and next to it, a staff member, a youngish Black woman with long dreads, was leaning against the wall reading a book.

I was looking – okay, yes, staring – at her because she was quite gorgeous, and after a while, she looked up and said, “It’s lint.”

The art piece, she said, was made of lint. It was her favorite piece in the museum.

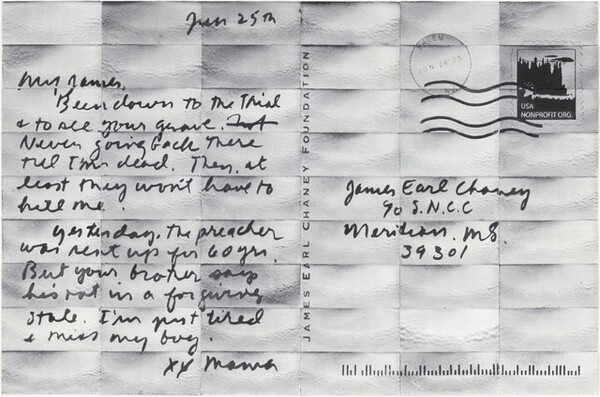

“My James” (2008) by American artist Mary Kelly

“My James,

Been down to the Trial & to see your grave. Never going back there until I’m dead. Then, at least they won’t have to kill me. Yesterday, the preacher was sent up for you. But your brother says he’s not in a forgiving state. I’m just tired & miss my boy.”

XX Mama”

I couldn’t verify if it's a real letter, but it’s written from the point of view of Fannie Lee Chaney, a Black baker from Mississippi. In 1964, her son James was killed by the Ku Klux Klan in a series of murders that came to be known as the Mississippi Burning killings. It roiled the country for months, eventually galvanizing support for the Civil Rights Act.

After speaking out about her son’s death in Mississippi, Chaney got death threats and her home and James’ grave were repeatedly vandalized. She moved to New York and didn’t return until 2005, when, at the age of 84, she testified in the trial against one of the Klansmen who killed James.

Been down to the Trial & to see your grave. Never going back there until I’m dead … I’m just tired & miss my boy.

I don’t know how Kelly, a conceptual artist from Iowa, got to know Chaney – or if she ever did. But I keep thinking about this piece. At the NGA, Ruairi and I stared at it for maybe 10 minutes, trying to decipher the text, letting elevators come and go. I found this 2017 Times review that said Kelly has been working with compressed lint since 1999, doing thousands of extra loads of laundry just to generate the material – “an ephemeral reminder of daily life or, more specifically, of the never-ending rhythms of women’s domestic labor.”

In New York, after the loss of her oldest son, Chaney worked for three decades as a cleaner in a nursing home, "changing linens and emptying bedpans." She would also have had done thousands of loads of laundry; would also have been familiar, I imagine, with the materiality of lint.

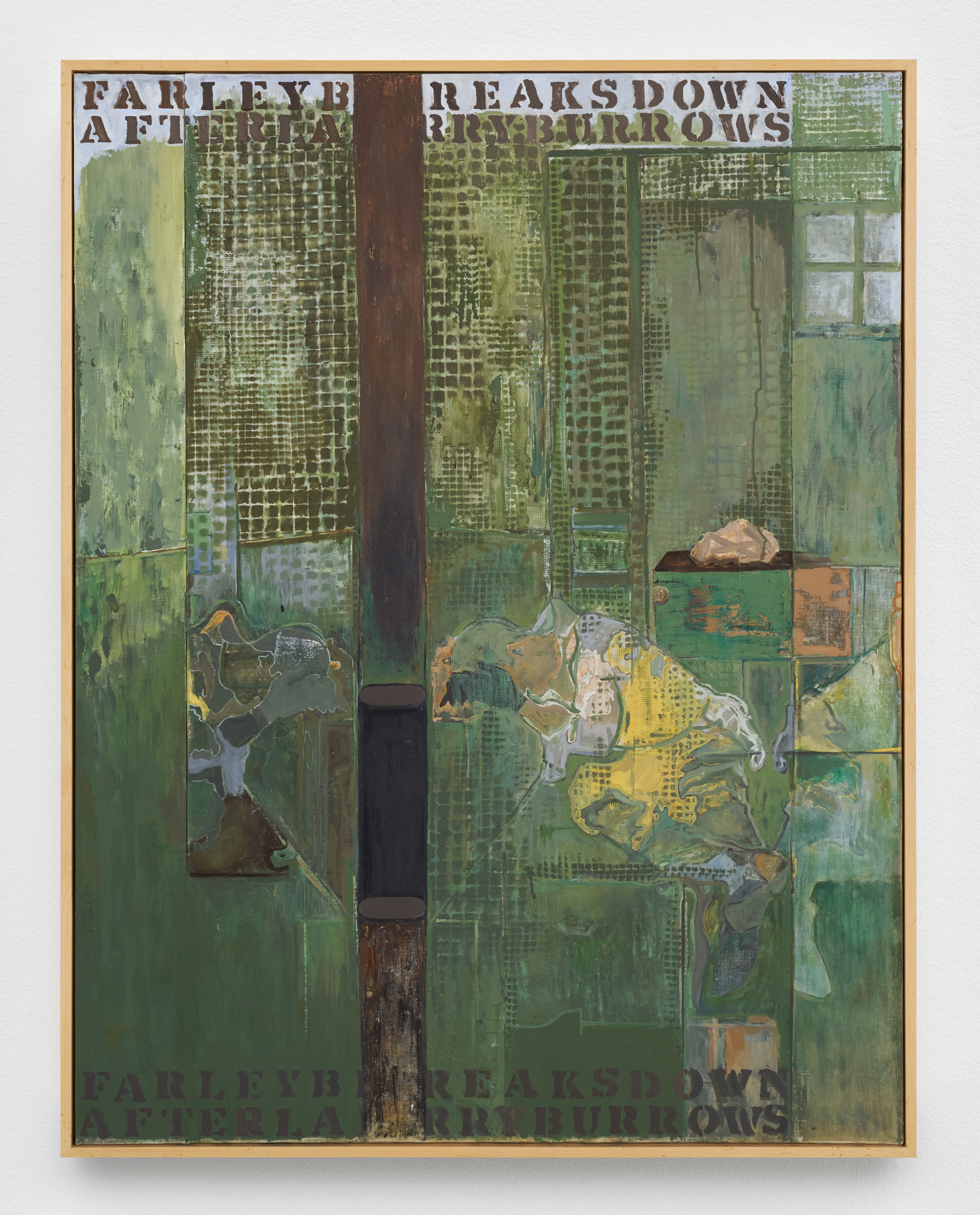

I was already thinking about this line of feeling – from Chaney to Kelly to the NGA employee to me – when we went to the Jasper Johns show at the PMA. It was quite an overwhelming three hours. Johns has been so prolific over his lifetime and he returned – is returning – so frequently to the same subjects, tensions, themes; even to the exact same images. One of them is this picture:

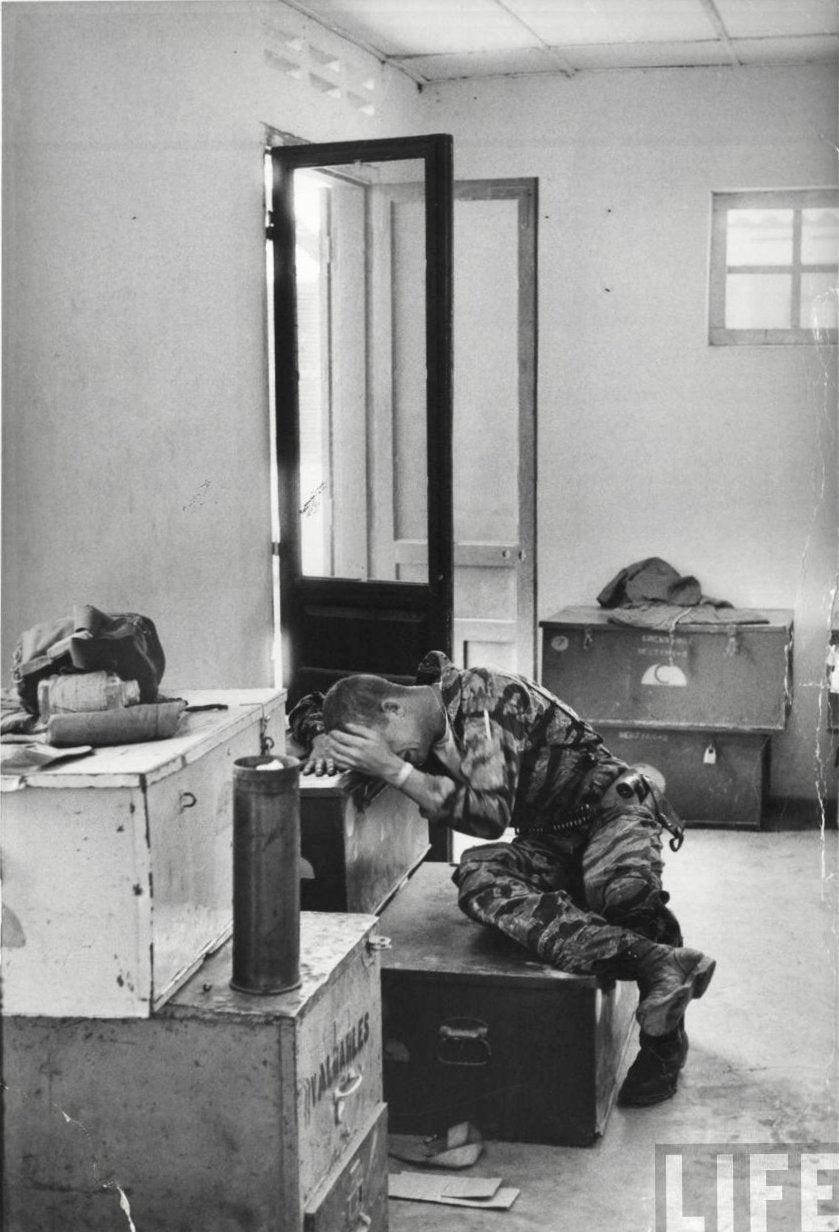

“Marine Lance Corporal James Farley Breaks Down in Office over the Death of Fellow Soldiers during the Vietnam War”

The image first ran in a Life Magazine photo essay in 1965, a year after James Chaney was killed by the KKK. It arrested the attention of people across the U.S., including Johns, who was 35 at the time, a decade out from his service in the Korean War and new to his art world celebrity. Johns made dozens of prints of this photo using different methods, coloring it, flipping it, cutting it apart. As recently as 2018, he was experimenting with ways to render it new.

Farley, the soldier, was 19 when the photo was taken. He was made the subject of countless profiles over the years and in 1996, the year many of us were born, he gave this interview to the Post:

"It embarrassed me for years."

And I say, "You mean because you're crying like that?"

He clears his throat, nods. "I guess because, well, it's not what a Marine is supposed to do. I guess it still bothers me, you want to know."

"But wouldn't anybody have felt the same thing if they'd gone through what you'd gone through that day?"

"Well, okay, I think anybody would feel it. But I guess it depends on how you show it."

"You mean that you didn't hold it in?"

He nods again. "Yes." Then: "That's right. That I didn't hold it in."

So I have been thinking about these two pieces of art.

I’m moved by the history they’re embedded in and moved also by the unlikely journeys they took to reach me. Like what Teju Cole says in his essay on Caravaggio: “A painting made by someone in a distant country hundreds of years ago, an artist’s careful attention and turbulent experience sedimented onto a stretched canvas, leaps out of the past to call you – to call you – to attention in the present.”

I do realize that both these pieces of art primarily convey sorrow, which I suppose is a feeling I am curious about because it’s something I happen to have distance from at this point in time, though I can still sort of spy it from the corner of my eye, latching onto people I love. I don’t know that I’ve ever felt despair, but my family can testify that I did have a long-term relationship with a garden variety, low-level misery that I’ve now mostly ditched. I know real sorrow will come at some point and in ways that I won’t be able to avert with the dumbfounding degree of privilege that has protected me from most bad things. I’m just now, at 25, more determined to live out the good times as they happen. To quit what makes me anxious (anything that Mark Zuckerberg touches, apparently) and engineer what makes me happy; to be less mournful about living in a capitalist, patriarchal moment in history and more animated by the ways in which we can – because we can – engage one another outside those parameters.

Maggie Nelson writes in her new book “On Freedom” that she’s skeptical of people who demean the ways that "feeling free, feeling good, feeling empowered, feeling communion, feeling potency can be literally contagious, can have the power to break up the illusion not only of the separateness of spheres, but also of our putative selves.”

Later, she adds:

"... Paranoia, despair, and anxiety are not known for helping us to 'stay with the trouble,' or to deepen our fellowship with one another. In fact, they tend to reify an already painful sense of individuation, and to constrict our imagination toward the very worst I can conjure, as if rehearsing our worst fears will lesson our future suffering. Extensive personal experience with this approach has taught me that it does not. Instead, I've come to know it as a completely understandable, extremely effective means of attenuating whatever liberation, expansiveness, or pleasure might be available in the present moment, and depriving oneself of it."

And David Graeber writes in “Possibilities”: “Revolutionary action is not a form of self-sacrifice, a grim dedication to doing what it takes to achieve a future world of freedom. It is the defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free.”

There is a lot of misery in the world that is outside our control – the things surrounding debt, housing, privacy, sickness or death are examples. I just want to learn how to expel the misery and the anxiety that is within reach, though of course, like all things worth doing, it's a process.

I love Haim’s song “Now I’m In It” and cannot tell you how many times I've danced to it in the shower. I always thought it was about euphoria, but after seeing Haim in concert two weeks ago, I looked up the song and turns out Danielle Haim wrote it about her struggle with depression:

Looking in the mirror again and again

Wishing the reflection would tell me something

I, I can't get a hold of myself

I can't get outta this situation

A process.

Other recommendations:

"Is Amazon Changing the Novel?" by the brilliant Parul Sehgal

The Netflix series "Maid," which is based off a memoir by Stephanie Land. (Ruairi and I are two episodes in and it's so good! We also recently watched Dune, which was a letdown.)

"Quarantine Sessions" by Tom Misch, "Letter Blue" by Wet, and of course "Blue Bannisters" by Lana Del Rey. The Lana album is not her best and I agree with critics that she's probably too productive for her own good, but there are gems in here. I love "Arcadia" about the suburbs outside L.A. and "... If You Lie Down With Me." And I can't stop laughing at this verse in "Sweet Carolina": You name your babe Lilac Heaven / After your iPhone 11 / "Crypto forever, " screams your stupid boyfriend / Fuck you, Kevin

Lots of poetry newsletters around, but I've enjoyed "Pome" by Matthew Ogle – "Short modern poems for your inbox."

Here's one that came recently:

About

Facts about the iris

Do not make the iris

Open. Open your eyes. It's tomorrow.

Call out for someone.

James Galvin

Your friend always,

Reb