Daybreak in Gaza

Dear Friends,

I still have stories to share about my time in the West Bank earlier this year, but I feel compelled to write about what’s happening now, especially Israel’s ongoing slaughter and starvation of the people of Gaza. So today I want to offer a chapter from a powerful book, Daybreak in Gaza: Stories of Palestinian Lives and Culture, which I just read as part of a Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) book club. Like these Postcards, the book consists of short, personal, first-hand accounts.

A review in Mondoweiss describes the book as “a compilation of writings from within the genocide by Gaza’s poets, authors, doctors, scientists, teachers, students, farmers, shopkeepers, children and their parents, etc. The writers share their pain, grief, and dismay – and their love of their captive homeland”.

The volume was compiled over three months, from March to May 2024. The editors Mahmoud Muna and Matthew Teller write, “At a time of profound anguish, bereavement, and loss, we found that Gazans — even those surviving starvation and bombardment inside Gaza — were not only willing to talk, but often desperate to do so. Stories poured out. In an unimaginable context of death and wholesale destruction, Gazans wanted urgently to be heard, to record and preserve whatever once counted as normal and valuable and meaningful.” Reading these stories is one way to honor that wish.

In one short essay, Noor Aldeen Hajjaj writes, “I am a Palestinian writer, I am twenty-seven years old and I have many dreams. I am not a number and I do not consent to my death being passing news. Say, too, that I love life, happiness, freedom, children’s laughter, the sea, coffee, writing, Fairouz, everything that is joyful… One of my dreams is for my books and my writings to travel the world, for my pen to have wings that no unstamped passport or visa rejection can hold back.”

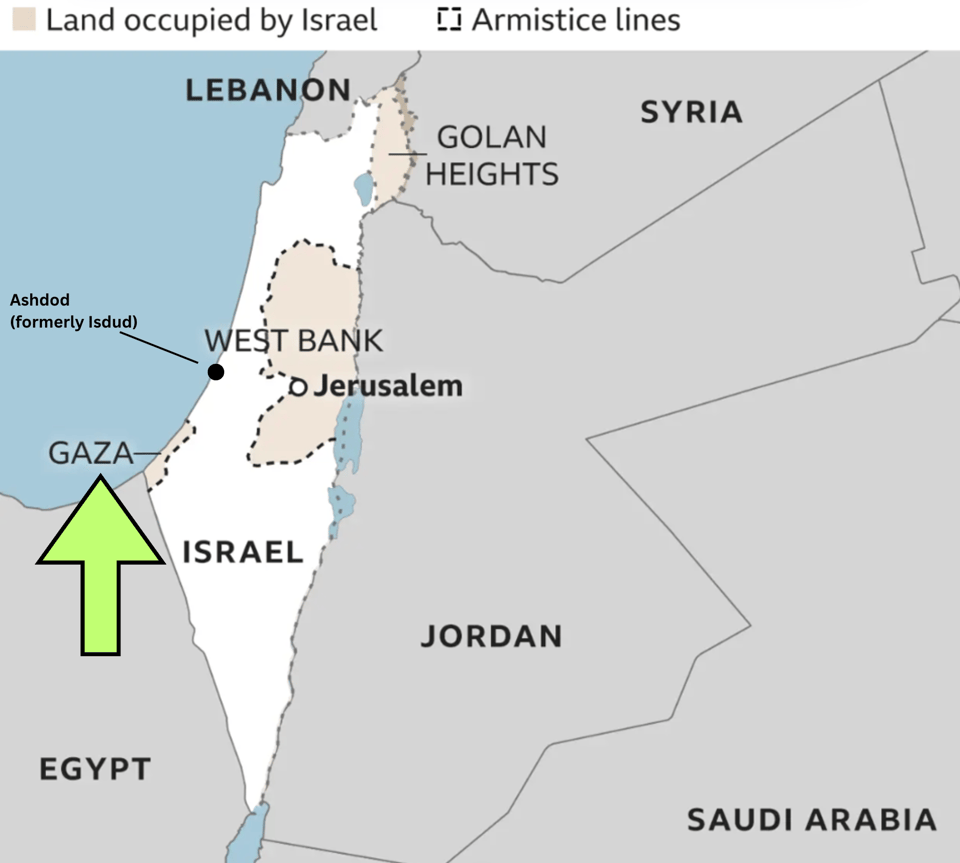

I will share one full chapter from the book below. The writer Mahmoud Joudeh contributed his essay in April 2024, translated by Jayyab Abusafia. Like many residents of Gaza, the author is a descendant of Palestinians who had been living in a city called Isdud, which is now the Israeli city of Ashdod. His family were first displaced as refugees to Gaza during the creation of the state of Israel, the 1948 Nakba.

I Cannot Lie

Mahmoud Joudeh

I trace my origins to Isdud [Ashdod], which was occupied in 1948, but I have spent my entire life in Gaza, the city after which this strip is named. Gaza is the whole world. We are locked inside it and most of us are unable to leave.

This city has always embraced difference: the church of St Porphyrius shares its wall with the mosque next door. I remember 25 December every year, when we would gather in St John the Baptist church in Gaza’s Old City, Muslims and Christians side by side in friendship, for the annual concert of music performed by musicians from Palestine and abroad. That has now disappeared, because the churches that were not destroyed are being used as shelters.

Gaza’s people have achieved miracles to communicate with the world in the language of the times. They made a city whose first cinema, Cinema al-Samer, opened in 1943. Their city hosts more than ten universities offering different disciplines, and dozens of cultural centres, libraries and theatres — the Said al-Mishael Theatre, Rashad al=Shawa Cultural Centre, the Red Crescent Theatre, Holst Cultural Centre, Abdul Mohsen al-Qattan Centre, and others. They created a city open to the world, where the streets are named after lovers, flowers and the sea, Libyan resistance hero Omar al-Mukhtar, French president Charles de Gaulle and United Nations mediator Count Bernadotte; where women have for generations gone out to work and study, engaging in civic life and leading institutions. Visitors come with preconceived notions and leave with changed perspectives, discovering that Gazans speak multiple languages, learning at a language centre affiliated with the UK’s leading universities. Gaza has made a beautiful world for itself. It is a city that seeks life passionately.

But Gazans don’t want to be called superheroes. Such labels ease the consciences of onlookers and justify their failure to support people in need. Superheroes need nobody, but we are the opposite; we are people just like everyone else, and we are currently the victims of ruthless aggression that strives to dehumanise Gazans and kill this hopeful Palestinian dream. One simple example. In 2000, Israeli warplanes bombed the Criminal Investigation Laboratory before its inauguration. This lab, developed in cooperation with European countries, was intended to help police identify perpetrators quickly and prevent rights violations during police investigations. But Israel preferred that the police retain their old ways, perpetuating the likelihood of violations and erosion of the rule of law.

Why are we besieged? Is it because we demand the implementation of United Nations resolutions? When will Britain apologise to my grandmother Khadra, who died in her daughter’s arms asking to be buried in the home from which the Balfour Declaration displaced her?

Many questions circle in my head, waiting for answers. Instead, I am sent rockets that have destroyed my life and made me a displaced person here in Cairo, searching for shelter, work and a school for my young children.

On 13 October 2023, Israel ordered the evacuation of al-Rimal neighbourhood, Gaza City’s most beautiful suburb, established in 1944. My seaside house there, beside the Orthodox Cultural Centre, where I wrote poetry and welcomed friends, was a modest home for my family: my wife Samar, who holds a master’s in business administration, my daughter Baghdad, just started in school, and my son Khaled, who learned to swim at the age of five and who now, after one hundred and fifty days of hunger and bombing and sleeping in a tent, asks me every day about his toys and the wooden bed I made for him, which he never slept in once. Khaled complains every night about being cold. The cold is a fearsome monster, beyond words. It eats your limbs. It stops your heart. It is an indescribable curse, felt only inside a tent.

‘This is the Israel Defense Forces. You have ten minutes to leave your home.’ Imagine with me: ten minutes and your tiny history is erased from the earth — your gifts and the photos of your siblings, the children who were martyred and those who still live, the things you love, your chair, your books, the last poetry collection you read, a letter from your sister living abroad, memories with your loved ones, the dress your grandmother Khadra wore when she had to flee, photos of your mother when she was young, holding you in her arms, the scent of your bed, the habit of touching the jasmine hanging in the window facing west, your daughter’s hair clip, the warmth of the seat, your old clothes, your prayer mat, your wife’s gold, your life’s savings.

Imagine all this passing before your eyes in just ten minutes, the pain sweeping over you as you stand in disbelief then grab your ID out of the sweet tin.

We left home with nothing but my daughter Baghdad’s school bag. Everything else, gone in an instant. I often think, what if we had stayed in the house? We would have died once. Instead, we left — and now we die a thousand times a day, from alienation, poverty and the loss of ambition and hope.

A never-ending series of torments because the so-called civilised world does not want to witness the crime in which it participates. We are the victim of their victim, who unleashes upon us the consequences of a historic crime we were never a part of. My grandparents were displaced from Isdud in 1948 and forced to live in a tent, and now we, their grandchildren, are displaced from Gaza in 2023 and forced to live in the same tent.

I am a writer and a poet with published work that speaks of goodness and beauty. Yet Israel stops us telling the world about our shared humanity by besieging us with continuous killing and a blockade that suffocates every detail of our days, trapping our senses within suffering so we can write about nothing else, draining our emotions until the world grows tired of us from the magnitude of the tragedy we demonstrate. If not for this suffering, we would swim in clearer, more sustaining waters. I don’t want my creativity to be linked to tragedy. My ambition is to create in innocence, freedom and beauty. But Israel and the silent countries of the world insist on dehumanising us to justify siege and extermination.

In March 2024, Rafah experienced a massacre, when occupation aircraft bombed inhabited homes while people were sleeping. It was around 2am and pitch dark. There were dozens of deaths. Part of my family’s home was destroyed. One of the victims of the darkness was a boy who survived the bombardment but was trapped under the rubble. We could see his head, but no one could rescue him because his foot was stuck, and there was no equipment to deal with such a situation. The civil defense had to amputate to free his leg and extract him, but he died soon after, a victim of aircraft, darkness, and Israel’s prohibition on rescue equipment.

After the massacre, when daylight came, residents gathered piles of bodies for burial. There were more than a hundred, in white shrouds. A journalist beside me tried several times to take a photo; he said the lens he was using was not wide enough to show them all. That day I met my friend Rima, a surgeon who had been displaced from al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza to Rafah’s Kuwaiti Hospital. She told me about her journey, dodging corpses on the road. As she walked she trod on a nail but had to limp on, with the nail hitting the bone, because the army’s instructions were clear: any stopping, turning, standing or bending would be met with a bullet.

This aggression has set us back decades, destroying our dreams before our eyes. I have never been pessimistic. I was the one writing about love and beauty, focusing my work on anything to summon up hope and peace. But now I find myself unable to support myself and my family. I cannot lie to them that the future will be beautiful while they witness human rights being violated openly, with nobody able to stop the killing. I do not want my children to grow up on tragedy and relief aid. We are a free and wealthy people, with resources and minds able to create a nation to be proud of.

As I write I am holding back my tears. We used to mourn for a person, a pet, a beautiful memory, a park we sat in, a street we walked on. Then we would mourn for a family, a house, a neighbourhood. Now, we mourn for all of Gaza.

Daybreak in Gaza can be purchased wherever books are sold. Profits from the book are donated to Medical Aid for Palestine.

Salaam,

Nancy