Christmas in Bethlehem

Dear Friends,

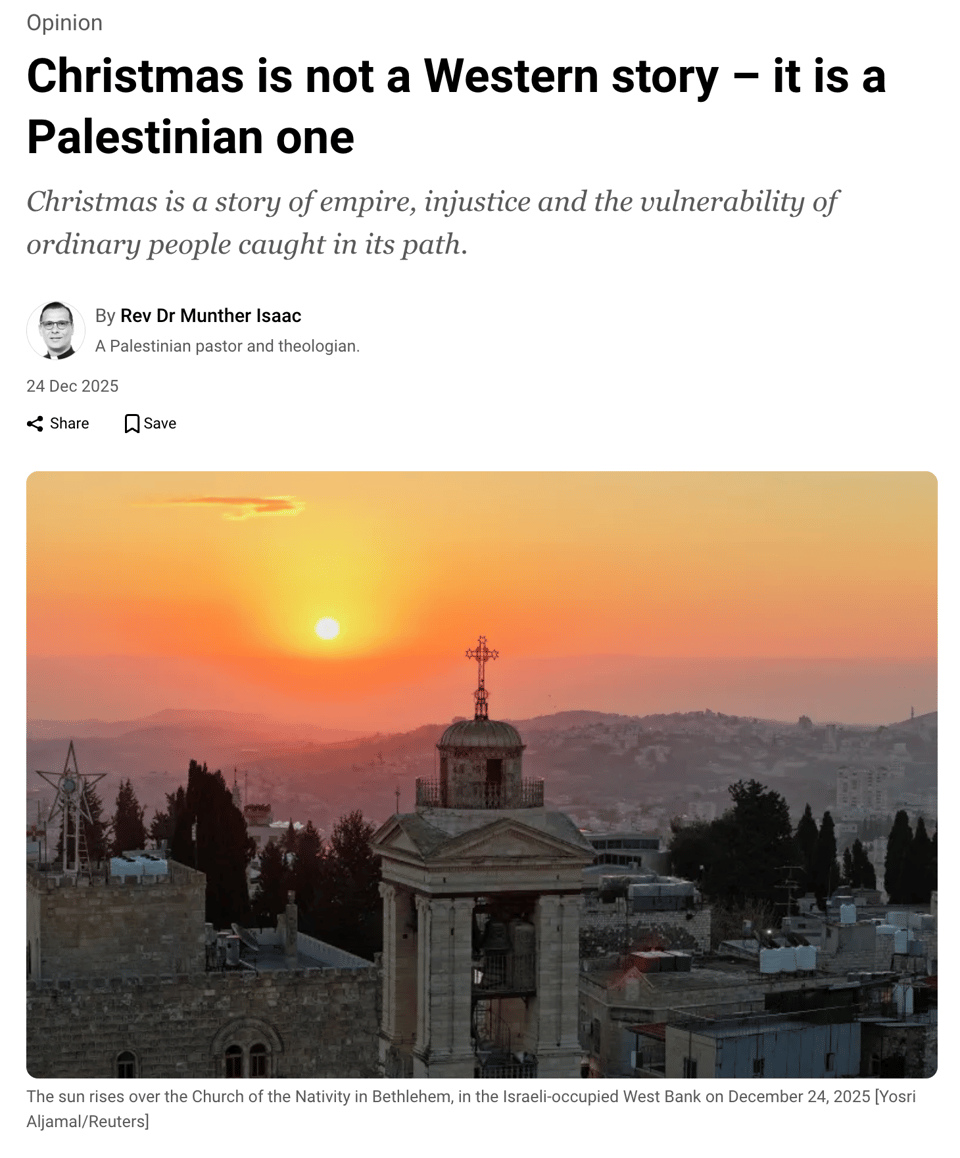

Merry Christmas to all who celebrate! It’s Christmas Eve here on the east coast of the US, and even though I think many of you won’t be opening email for a few days, I want to share a beautiful short essay by Reverend Dr. Munther Isaac, published today in Al Jazeera. Reverend Isaac reminds us all that Christmas is the birth story of a Palestinian Jew, “a child of this land who was born long before modern borders and identities emerged”. I’ll share the piece in full below, but here is a short excerpt.

“For many in the West, Bethlehem – the birthplace of Jesus – is a place of imagination — a postcard from antiquity, frozen in time. The ‘little town’ is remembered as a quaint village from scripture rather than a living, breathing city with actual people, with a distinct history and culture. Bethlehem today is surrounded by walls and checkpoints built by an occupier. Its residents live under a system of apartheid and fragmentation. Many feel cut off, not only from Jerusalem – which the occupier does not allow them to visit – but also from the global Christian imagination that venerates Bethlehem’s past while often ignoring its present.”

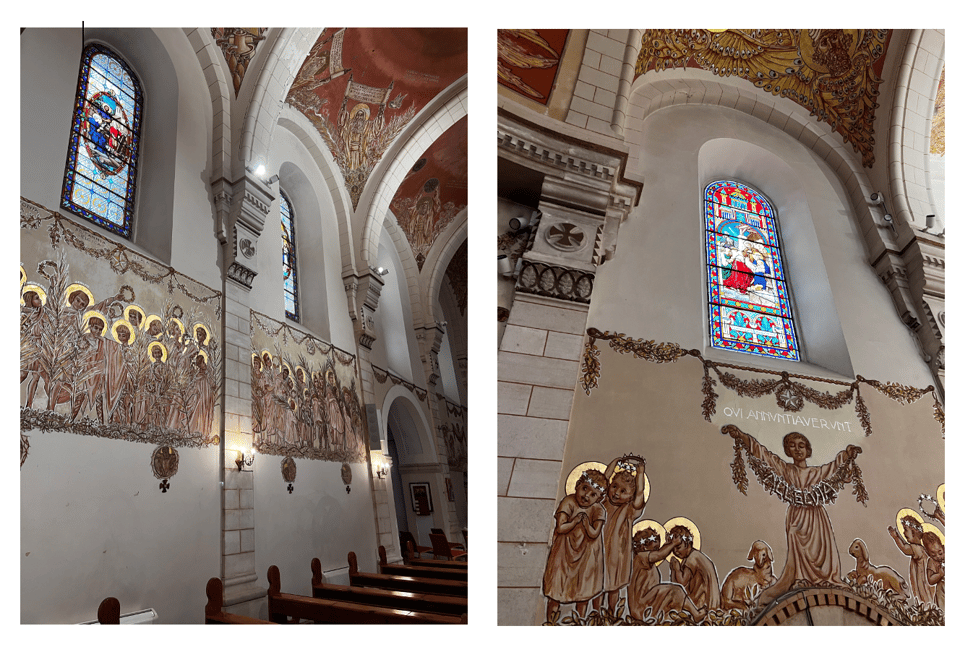

Life in Bethlehem today:

Some photos I took there earlier this year

.

Life in Bethlehem today:

Violence from Israeli settlers and soldiers

As you’ve probably read in the news, there has been a lot of violence against Palestinians by Israeli residents of these illegal settlements. According to the UN, the ICC (International Criminal Court), the ICJ (International Court of Justice), and the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross), Israeli settlements in the West Bank are in violation of international law. Although this is not new, violence by settlers - under the full protection of the Israeli military - has been surging in recent years and even more so in recent months, so that it is now a daily occurrence.

Reverend Dr. Munther Isaac’s essay

Every December, much of the Christian world enters a familiar cycle of celebration: carols, lights, decorated trees, consumer frenzy and the warm imagery of a snowy night. In the United States and Europe, public discourse often speaks of “Western Christian values”, or even the vague notion of “Judeo-Christian civilisation”. These phrases have become so common that many assume, almost automatically, that Christianity is inherently a Western religion — an expression of European culture, history and identity.

It is not.

Christianity is, and has always been, a West Asian / Middle Eastern religion. Its geography, culture, worldview and founding stories are rooted in this land — among peoples, languages and social structures that look far more like those in today’s Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Jordan than anything imagined in Europe. Even Judaism, invoked in the term “Judeo-Christian values”, is itself a thoroughly Middle Eastern phenomenon. The West received Christianity — it certainly did not give birth to it.

And perhaps nothing reveals the distance between Christianity’s origins and its contemporary Western expression more starkly than Christmas — the birth story of a Palestinian Jew, a child of this land who was born long before modern borders and identities emerged.

What the West made of Christmas

In the West, Christmas is a cultural marketplace. It is commercialised, romanticised and wrapped in layers of sentimentality. Lavish gift-giving overshadows any concern for the poor. The season has become a performance of abundance, nostalgia, and consumerism — a holiday stripped of its theological and moral core.

Even the familiar lines of the Christmas song Silent Night obscure the true nature of the story: Jesus was not born into serenity but into upheaval.

He was born under military occupation, to a family displaced by an imperial decree, in a region living under the shadow of violence. The holy family were forced to flee as refugees because the infants of Bethlehem, according to the Gospel narrative, were massacred by a fearful tyrant determined to preserve his reign. Sound familiar?

Indeed, Christmas is a story of empire, injustice and the vulnerability of ordinary people caught in its path.

Bethlehem: Imagination vs reality

For many in the West, Bethlehem – the birthplace of Jesus – is a place of imagination — a postcard from antiquity, frozen in time. The “little town” is remembered as a quaint village from scripture rather than a living, breathing city with actual people, with a distinct history and culture.

Bethlehem today is surrounded by walls and checkpoints built by an occupier. Its residents live under a system of apartheid and fragmentation. Many feel cut off, not only from Jerusalem – which the occupier does not allow them to visit – but also from the global Christian imagination that venerates Bethlehem’s past while often ignoring its present.

This sentiment also explains why so many in the West, while celebrating Christmas, care little about the Christians of Bethlehem. Even worse, many embrace theologies and political attitudes that erase or dismiss our presence entirely in order to support Israel, the empire of today.

In these frameworks, ancient Bethlehem is cherished as a sacred idea, but modern Bethlehem — with its Palestinian Christians suffering and struggling to survive — is an inconvenient reality that needs to be ignored.

This disconnect matters. When Western Christians forget that Bethlehem is real, they disconnect from their spiritual roots. And when they forget that Bethlehem is real, they also forget that the story of Christmas is real.

They forget that it unfolded among a people who lived under empire, who faced displacement, who longed for justice, and who believed that God was not distant but among them.

What Christmas means for Bethlehem

So what does Christmas look like when told from the perspective of the people who still live where it all began — the Palestinian Christians? What meaning does it hold for a tiny community that has preserved its faith for two millennia?

At its heart, Christmas is the story of the solidarity of God.

It is the story of God who does not rule from afar, but is present among the people and takes the side of those on the margins. The incarnation — the belief that God took on flesh — is not a metaphysical abstraction. It is a radical statement about where God chooses to dwell: in vulnerability, in poverty, among the occupied, among those with no power except the power of hope.

In the Bethlehem story, God identifies not with emperors but with those suffering under empire — its victims. God comes not as a warrior but as an infant. God is present not in a palace but in a manger. This is divine solidarity in its most striking form: God joins the most vulnerable part of humanity.

Christmas, then, is the proclamation of a God who confronts the logic of empire.

For Palestinians today, this is not merely theology — it is lived experience. When we read the Christmas story, we recognise our own world: the census that forced Mary and Joseph to travel resembles the permits, checkpoints and bureaucratic controls that shape our daily lives today. The holy family’s flight resonates with the millions of refugees who have fled wars across our region. Herod’s violence echoes in the violence we see around us.

Christmas is a Palestinian story par excellence.

A message to the world

Bethlehem celebrates Christmas for the first time after two years without public festivities. It was painful yet necessary for us to cancel our celebrations; we had no choice.

A genocide was unfolding in Gaza, and as people who still live in the homeland of Christmas, we could not pretend otherwise. We could not celebrate the birth of Jesus while children his age were being pulled dead from the rubble.

Celebrating this season does not mean the war, the genocide, or the structures of apartheid have ended. People are still being killed. We are still besieged.

Instead, our celebration is an act of resilience — a declaration that we are still here, that Bethlehem remains the capital of Christmas, and that the story this town tells must continue.

At a time when Western political discourse increasingly weaponises Christianity as a marker of cultural identity — often excluding the very people among whom Christianity was born — it is vital to return to the roots of this story.

This Christmas, our invitation to the global church — and to Western Christians in particular — is to remember where the story began. To remember that Bethlehem is not a myth but a place where people still live. If the Christian world is to honour the meaning of Christmas, it must turn its gaze to Bethlehem — not the imagined one, but the real one, a town whose people today still cry out for justice, dignity and peace.

To remember Bethlehem is to remember that God stands with the oppressed — and that the followers of Jesus are called to do the same.

Salaam,

Nancy