The hollowness of Hollywood’s rich people stories

TV and film of the moment aren't going to galvanize anyone. But stories closer to home just might.

On BlueSky this week, amid the release of various emails between Jeffrey Epstein and his cronies, the political scientist John Cluverius made this observation:

The Epstein story gets at something that is tearing at the heart of the electorate: elite impunity. The idea that wealthy and powerful people can do terrible things at scale and face no consequences for them. Whatever political party actually stops it could rule the country for a generation.

It’s striking how consistent Hollywood has been on this equation, in terms of where the storytelling energy lands.

Even the idea that anyone could throw a wrench into the status quo of “terrible things/no consequences” is apparently considered so unrealistic, or laughable, or just, I dunno, embarrassingly earnest moralizing as to be ignored entirely.

I was thinking about this, because I am always thinking about this. A friend recently mentioned an episode of NPR’s “It’s Been A Minute” from last month and the topic du jour: Rich people stories that have been proliferating in TV and film. Or more specifically, eat-the-rich stories.

I’ve written a lot about Hollywood’s weird fascination with the wealthy, which has only intensified in the last decade. And in fact, I was a guest on “It’s Been a Minute” two years ago talking about this very thing.

It’s a topic worth revisiting! I always appreciate conversations that push us to think more critically about the kinds of stories Hollywood is pumping out, even if I disagree with some of the points made in this episode.

Early on, host Brittany Luse makes the observation that pop culture “responds to our attitudes.“ The non-rich among us are increasingly skeptical of, and frustrated with, whatever you want to call this form capitalism we’re stuck in right now. Hence, Hollywood is responding to that.

It’s not that I disagree with that statement. I mean, I do. But it’s probably more instructive to think about the reverse: Instead of “How are our attitudes being reflected in TV and film?” I think the better question is “How is pop culture attempting to shape and mold attitudes?”

Because if Hollywood were really responding to a collective shift in attitude, you’d be seeing a very different array of themes in TV and film.

Instead, it’s just more shows about rich people.

Let’s get specific

I’ve long argued that escapism doesn’t have to be packaged this way. And yet, increasingly it is. We should be asking why and what effect it’s supposed to have on our worldview.

Most American and British efforts to skewer the rich — from “Succession” to “The White Lotus” to countless others — are thematically hollow.

Yes, the main characters are miserable despite all their money. But their angst and anxieties, their wants and needs, their precious feelings, are not just played for satiric laughs — they are prioritized and centered.

That’s not eat-the-rich, but the equivalent of a Friars Club roast of the rich.

Just as importantly, there is no one within these fictional worlds to mount a full-throated critique. Or organize strategies to chip away at the power class. These kinds of characters do not exist on screen in any meaningful sense. They remain out of sight and out of mind. They might as well not even exist.

Let’s get specific-er

There’s a family softball game that takes place in the first episode of “Succession” and because one team is in need of an additional player, a groundskeeper’s preteen son is pulled into service.

A million dollar check is dangled if the boy scores, only to have it torn up in his face moments later.

The Roys give no thought to how this might affect a child. They simply pile into their helicopters, metaphorically rising above those kinds of earthly concerns.

The human beings who remain on the ground below? Mere dots, to borrow from 1949’s “The Third Man,” and the Roys will spare no thought or pity if any one of those dots stopped moving forever.

In the conception of shows like “Succession” and so many others, the wealthiest are their own worst enemy. But anyone outside their exclusive, robber baron bubbles — people who might pose a serious challenge to their power structures — is apparently of no narrative interest.

It’s not just the money so much as the normalizing and whitewashing of corruption that it buys. We know that in the real world, extreme wealth can, and often does, undermine the basic functions of a democracy, paving the way for two other -ocracies instead: autocracy and kleptocracy

Nevertheless, the subtext of these shows is clear: The system is permanently rigged, so the best Hollywood can offer is an opportunity to laugh and shake our heads at these very rich, very unhappy buffoons.

What if … ?

I don’t know if attempts to understand the psychology of wealthy people are actually all that useful. Or even entertaining. (This TED Talk, titled “Does money make you mean?,” encapsulates the psychopathy in less than 20 minutes!)

Of course we never see the groundskeeper or his son again in “Succession’s” four-season run. They are as insignificant to show creator Jesse Armstrong as they are to the Roys themselves.

But what if Armstrong had allowed himself to de-center the Roys?

What if the groundskeeper’s son was radicalized by that experience at the softball game? What if he grew into a young person who organized with others to at least try to subvert some of the steamroller methods of the country’s wealthiest figures?

In the show’s second season, the Roys acquire and then destroy a digital media outlet called Vaulter (a riff on Vulture).

What if those journalists launched a scrappy, worker-owned outlet in response to root out compromising evidence of the Roy family’s corruption?

Maybe a pointless question, because the show’s overall framework isn’t built for this kind of storytelling.

“Succession” isn’t glamorizing the people who inhabit these elite, brutalist spheres, but it also has little to say about the systems these same people create and exploit. In fact, those systems are treated as unquestioned facts of life.

Hollywood itself is run by captains of industry who, as real-world Roy equivalents, probably see the world the same way. Which is perhaps why major TV and movie studios are, by and large, not making stories about regular people mounting a sustained effort to reorganize society so that the rich aren’t so unequivocally at the top and wrecking destruction.

I’ve seen a few people speculate that it’s unlikely Paul Thomas Anderson’s “One Battle After Another” would have been greenlit if it were pitched today, rather than a few years ago. That’s not so much a comment on the movie, but the kinds of storytelling studios are willing to back right now.

Storytelling — the right kind of storytelling — can have a galvanizing effect. Sometimes, seeing something play out in a fictional context helps your brain start asking, even subconsciously: What would I do in that situation?

For the foreseeable future, I don’t expect Hollywood to back anything that comes close to doing this.

I would be thrilled to be proven wrong.

Korea always has us beat on this front

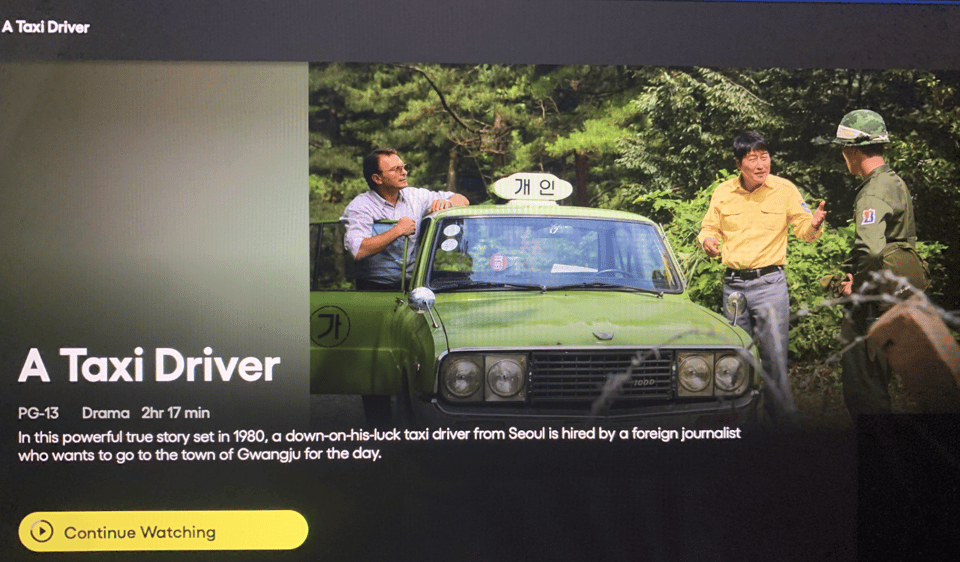

There’s a lot of awareness in the U.S. of “Parasite” and “Squid Game,” but perhaps less so when it comes to the 2017 film “A Taxi Driver.” It was South Korea’s Oscar submission for best foreign film a few years back and is currently streaming for free on Pluto.

It’s a comedy, at least initially. Set in 1980 and based on a true story, it begins with a cabbie in Seoul who finds himself stuck in traffic thanks to political protests and chants of “Throw out the dictatorship and bring in democracy!”

“Spoiled bastards need to be shipped off to Saudi Arabia,” he grumbles from his lime green taxi. “Work themselves to death in the burning desert, then they’ll realize, ‘Wow, my country is great!’”

He’s a widower who is behind on rent and raising a preteen daughter alone, and he only thinks of the protests in terms of how they interfere with his ability to earn a living.

And then he picks up a German journalist who is headed to the city of Gwangju to report on what would later become known as the Gwanju Uprising, a series of protests against the authoritarian government that had seized power in a coup the year prior. Mass killings followed, at the hands of the military.

The taxi driver is something of a ding-dong who isn’t really interested in what’s happening politically. He’s selfish and annoying to everyone. A humorous curmudgeon. But this trip opens his eyes and he is horrified enough to rise to the occasion.

It’s the story of strangers who come together — the cabbie, the journalist, plus some student protesters, as well as the cabbies of Gwangju — to establish a shaky trust and stand up for one another in order to do something meaningful in the face of something terrifying.

“A Taxi Driver” is a specifically Korean story, but Hollywood used to make similar stories.

The 1939 comedy “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” comes to mind. Plenty of elected officials were unhappy with the movie when it came out, going so far as to call it anti-American. Audiences felt otherwise. Not only was it the second highest-grossing film of 1939, it was the third highest-grossing film of the decade.

I’m trying to picture a Hollywood executive today greenlighting a movie about an underdog who faces down a corrupt federal government that’s been hijacked by an unelected but very wealthy man and … yeah.

So what does galvanize people right now?

We’re still influenced by images on our screens. Our phone screens.

On a daily basis in Chicago, the city and its suburbs have been subject to sustained violent raids aimed at immigrants. Or anyone who “looks” like an immigrant. Or dares to speak their mind. Or just happens to be nearby. It’s been very bad for several weeks.

I don’t know how much awareness of this there is outside of Chicago. But there’s a lot of local reporting. And a lot of video showing up on social media, because many of these raids are caught on camera.

Often you see onlookers blowing whistles and shouting at these armed men to go away. (The whistles are being widely distributed across different communities, and people are encouraged to use them to alert their neighbors to ICE sightings and activity.)

These raids have been happening across a variety of neighborhoods — some of which might have previously assumed they were “off limits” for various socioeconomic and racial reasons — and I do think there’s a galvanizing effect of seeing people who aren’t typically involved as activists push back and, in some cases, prevent individuals from being grabbed.

When I say it’s happening on a daily basis, I mean even on the weekends. On a Saturday morning, as kids were getting ready for a Halloween parade on the city’s Northwest Side, a former Cook County prosecutor named Brian Kolp was at home enjoying a slow morning, which took a turn when he “sprang into action, as he sometimes wondered he would have to do throughout the Trump administration’s ‘Operation Midway Blitz’ these last two months,” reported my Tribune colleagues.

Moments earlier, he had been “drinking coffee on his couch and watching the news as he always does on Saturday morning when he saw what’s become an all-too-familiar scene unfold outside his window. Two U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agents were tackling a man to the ground on his front yard. Meanwhile, Kolp’s TV continued to blare a news segment discussing the ongoing temporary restraining order restricting federal immigration agents’ use of tear gas.”

He didn’t have time to even put on shoes or change his clothing — he was barefoot and wearing a sweatshirt and brightly colored Chicago Blackhawks pajama pants at the time, “drawing jeers from one of the agents as he screamed ‘Nazis!’ and ‘Gestapo!’ at the agents.”

Those Blackhawks pajamas were a detail many of us noticed in the videos that were shared online. By day, he’s an attorney who likely wears a suit. But in this moment, he was an everyman in pajama pants bearing the logo of the local NHL team.

Like I said, sometimes you need to see something play out to help your brain start asking: What would I do?

Can pop culture tell hero stories that aren’t corny?

After years of antihero stories dominating our screens, writer-producer Vince Gilligan (creator of “Breaking Bad,” “Better Call Saul” and “Pluribus”) gave a speech back in March challenging the viability of this trend:

“We are living in an era where bad guys, the real-life kind, are running amuck.”

He urged his fellow screenwriters to reconsider valorizing “bad guys who make their own rules, bad guys who, no matter what they tell you, are only out for themselves.”

Bad guys can be fun characters! And I think that’s also why heroes get a corny rep — they want to ruin the good time of the antiheroes.

When a story does take heroes seriously, it’s because they have extra powers, as cops or superheroes, whereas normies are left on the sidelines, waiting to be saved.

This brings me back to the question posed earlier about whether pop culture responds to our attitudes, or is actually working to shape them. More often than not, I think it’s the latter.

Because consider who Hollywood portrays as heroes, and then consider this piece that ran in The Guardian last week with the headline: ‘Heroic actions are a natural tendency’: why bystander apathy is a myth

Here’s an excerpt:

Is there a hero inside all of us? Experts in bystander intervention say there is; that we are all more likely than not to act with selfless heroism in moments of acute threat.

“The notion that people panic and run screaming for the exits is a Hollywood fiction,” said Prof. Stephen Reicher, an expert in group behaviour at the University of St Andrews.

According to another specialist in crowd psychology and group identity:

“What modern research shows is that the public are very good at protecting themselves and that the heroic actions that hit the headlines are actually underlying, natural tendencies in all of us.”

That, he said, revealed something very positive about the human condition – but it also indicated that society would benefit from fostering and harnessing this natural capability by helping people to feel empowered to take control during emergencies.

“This will become increasingly important because of the broader challenges society will soon face.”

In what ways are the stories we see on our screens fostering — or undercutting — those natural tendencies?

Even when Hollywood centers a regular person who is reluctantly transformed into a hero, it’s often a lone man who has been backed into circumstance, but is driven by noble intentions. Invariably, he wears an expression of: Fine, I’ll save the day. This is true of every variation on “Die Hard,” including the Idris Elba series “Hijack” on Apple, which is back for a second season in January.

What if more stories explored what it takes fight for a functional society? What it takes for people to come together as a group to become their own heroes?

Gennifer Hutchison was a writer on “Breaking Bad” and after Gilligan’s speech last spring, she posted some thoughts of her own that drilled down even further:

Being good/a hero — and by that I mean, making the best choices one can to help others, do no harm and make things better — is hard as hell in a world that is often cruel and rewards selfish behavior.

I see folks dismissing “heroes” as boot-licking, prissy rule-followers, while characterizing “villains” as the marginalized fighting oppressive systems and it makes me so frustrated because flip that.

Show the messiness of what it takes to MAKE SHIT BETTER. What you have to break in order to do so and WHY THAT IS JUST. Show the sacrifices.

She’s right! There’s a lot of drama and absurdist comedy in that kind of premise.

We can’t go it alone.

And we can’t wait for Hollywood to show us the way.

But it would be nice if Hollywood reflected back to us more of that shift that’s so evidently in the air.