Not Proud and Near the Ground

Why I named this newsletter Humble Theory

Dear Reader,

Today I want to explain why I chose Humble Theory for the title of my newsletter. As I shared previously, I’m borrowing (with permission) the term from Dorry Noyes. Noyes was one of my amazing folklore professors as an undergrad at Ohio State in the late aughts. But I didn’t read her writing on Humble Theory until a decade later when I was a grad student in folk studies at Western Kentucky University (shoutout to my other amazing folklore professor, Ann Ferrell, for assigning it).

Noyes published her article “Humble Theory”1 in 2008 at a time when the field of folklore was having (yet another) identity crisis. The study of folklore in the United States has roots in both literary studies and anthropology, and it emerged as its own academic discipline in the mid-20th century. Since then, folklorists have been perpetually attempting to carve out and maintain a space for the discipline within academia, trying to make sure everyone understands the field’s importance and distinction from other related disciplines. As Noyes describes it, we’ve long suffered a serious case of “status anxiety” and “theory envy” within the field of folklore. We imagine ourselves occupying one of the lowest rungs on “the imagined ladder toward transcendent knowledge,” and we are not okay about it.

At the time Noyes wrote “Humble Theory,” the particular question folklorists were grappling with was “Why is there no GRAND theory in folkloristics?” If “theory” is a framework for explaining why certain things are the way they are, “grand theory” refers to the big, broad, universal ideas that attempt to explain fundamental aspects of society.

But folklorists don’t tend to be that interested in the big, broad, or universal. We generally find ourselves in the weeds of the particulars, looking at how everyday people creatively express themselves and make meaning in their everyday lives. Folklorists look at a range of expressive cultural forms: things like food, dance, music, craft, dress, slang, beliefs, work, play, celebratory customs, storytelling—and much, much more. We’re interested in the ways that traditions are passed on from one generation to another, and how some elements remain the same while others are updated to fit the present moment. We’re interested in how these community-based practices construct peoples’ identity and sense of belonging, and how they can serve as modes of resistance and reflection. Or as Noyes puts it, folklorists deal with “the residual, the emergent, and the interstitial.”

So what was Noyes’ response to the question of “Why is there no GRAND theory in folkloristics?” She said we don’t need grand theory, ‘cause we’ve got h u m b l e theory, baby. Quoting Charlotte the Spider from E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, Noyes reminds us that “humble” means “‘not proud and near the ground.’” As folklorists, we not only study cultural forms that are near the ground; we also look at how people and communities understand these cultural forms for themselves. And this is where our theory emerges—from the particulars of our fieldwork with specific people in specific communities in specific places. Noyes contends that in our theory-making “[folklorists] would be better off cultivating shamelessness. If we are proud of anything, to be sure, it is of being near the ground.”

So how does all of this relate to my own creative practice and desire to document it and share about it via this newsletter?

Noyes posits that “folklore is a trinity,” it relies on three things: ethnography, social and public practice, and theory. She explains,

The field cannot theorize without strongly grounded, in-depth ethnography of particulars. The field has no purpose without engagement in the world, trying to understand and amend the social processes that created the F-word [folklore] and other, far worse stigmas. Practice in the world has no lasting efficacy without theory to clarify its means and ends and make its efforts cumulative. The ethnographer, the practitioner, and the theorist are mutually dependent and mutually constitutive: they cohabit, to different degrees, in singular folklorist bodies.This frame very much maps onto my experience as a folklorist and as an artist.

Artist as Ethnographer

My art practice requires that I am an ethnographer, that I pay attention to, document, and archive what I experience and witness in my day-to-day life. This fieldwork is the fertilizer that helps grow the seeds of creativity.

Artist as Practitioner

My art practice also requires engagement, it requires me to actually practice creating. Because if I’m not making art…then I’m not making art! I think of this, too, in terms of social practice as Noyes describes. I very often reflect on how my art practice can have a positive impact. Of course there’s the impact it has on me personally: if I’m not creating, I become stagnant, anxious, depressed—making art helps me wade the choppy waters of life, and it helps me tap into joy and feel most like myself. My art practice is also sometimes an avenue for community care. Whether I’m raffling off a painting to raise funds for mutual aid or helping others overcome perfectionism and other creative anxieties in low- and no-cost quilt workshops, I believe there are opportunities—however small—to buck against oppressive social processes through art making.

Artist as Theorist

Finally, I do believe that my art practice requires theory for me to understand what I’m doing and why, and to build upon what I learn. I don’t think I realized until recently how much I desire theoretical grounding, how adrift I feel without it. And this is where the newsletter really comes into play. I think about creativity a lot. In fact, a good friend recently told me that she doesn’t know anyone else who thinks about creativity as much as I do. Of course, this is partly what drew me to become a folklorist—the fact that part of the gig is engaging with the creative process (albeit, primarily the creative process of others). Yet while I often think about creativity, it’s writing about it that really enables me to come to a place of understanding, of integration.

While I know engaging with theory is good medicine, sharing my theoretical musings about creativity feels quite vulnerable. I admit that like some academic folklorists, I often navigate status anxiety as an artist. It’s easy for me to talk myself out of sharing my work, believing that it occupies too low of a rung on the imagined ladder of excellence to really matter. I realize this thinking is totally antithetical to the foundation of folkloristics, which posits that everyone’s creativity matters (sometimes there’s nothing like being your own worst critic!). Luckily, this anxiety softens when I remember that my theories, and my art, can be h u m b l e.

Noyes says that, “humble theory recognizes that all our work is essay, in the etymological sense: a trying-out of interpretation, a provisional framing to see how it looks.” I want this idea to guide my newsletter practice. I want to remember that it’s just a practice in trying out ideas to see how they look, how they fit. I’m not attempting to make grand declarations here, I’m just attempting to tend my humble garden, near the ground, and share whatever the fruits of my labors are with others.

1 Noyes, Dorry. “Humble Theory.” The Question of Grand Theory. Special issue of the Journal of Folklore Research 45 (2008): 37-43.

Fieldnotes:

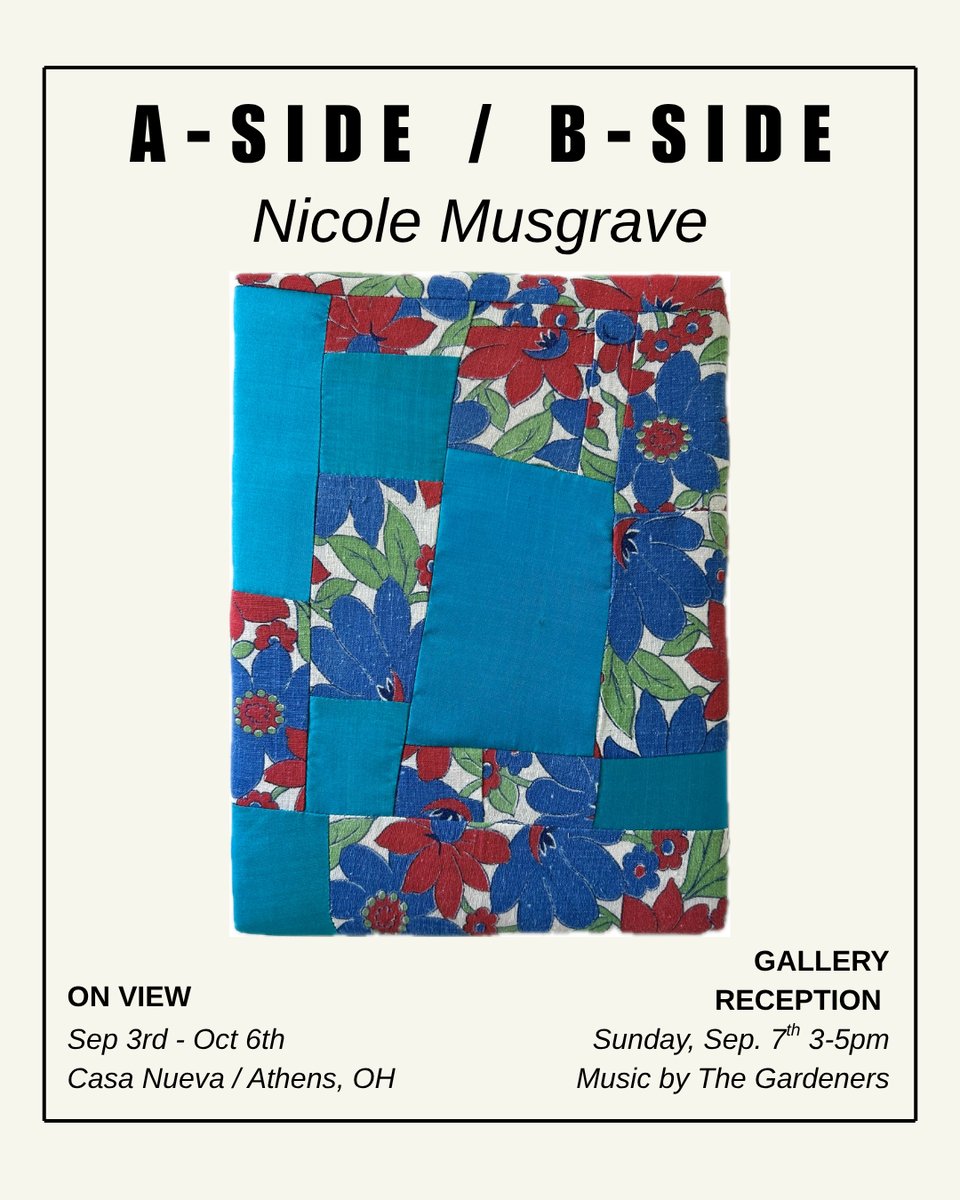

I have an art show in September at Casa Nueva in Athens, OH. Come on out to the gallery reception on September 7th!

A radio story I produced and edited about the late east Tennessee luthier Jean Horner was recently picked up by NPR. It’s a really sweet story from reporter Lisa Coffman and you should give it a listen :)

Jean Horner at his woodpile, photo by Mike Whitehead. This fall and winter, I’ll be teaching a series of quilt classes to clients of My Sister's Place, an organization in Athens, Ohio that provides support to domestic violence survivors. We’re seeking donations of supplies such as:

second-hand fabric of any kind (can include old clothing, sheets, tablecloths, curtains, etc.)

batting

sewing machines

needles and thread

If there’s anything you’d like to contribute, please respond to this email :)

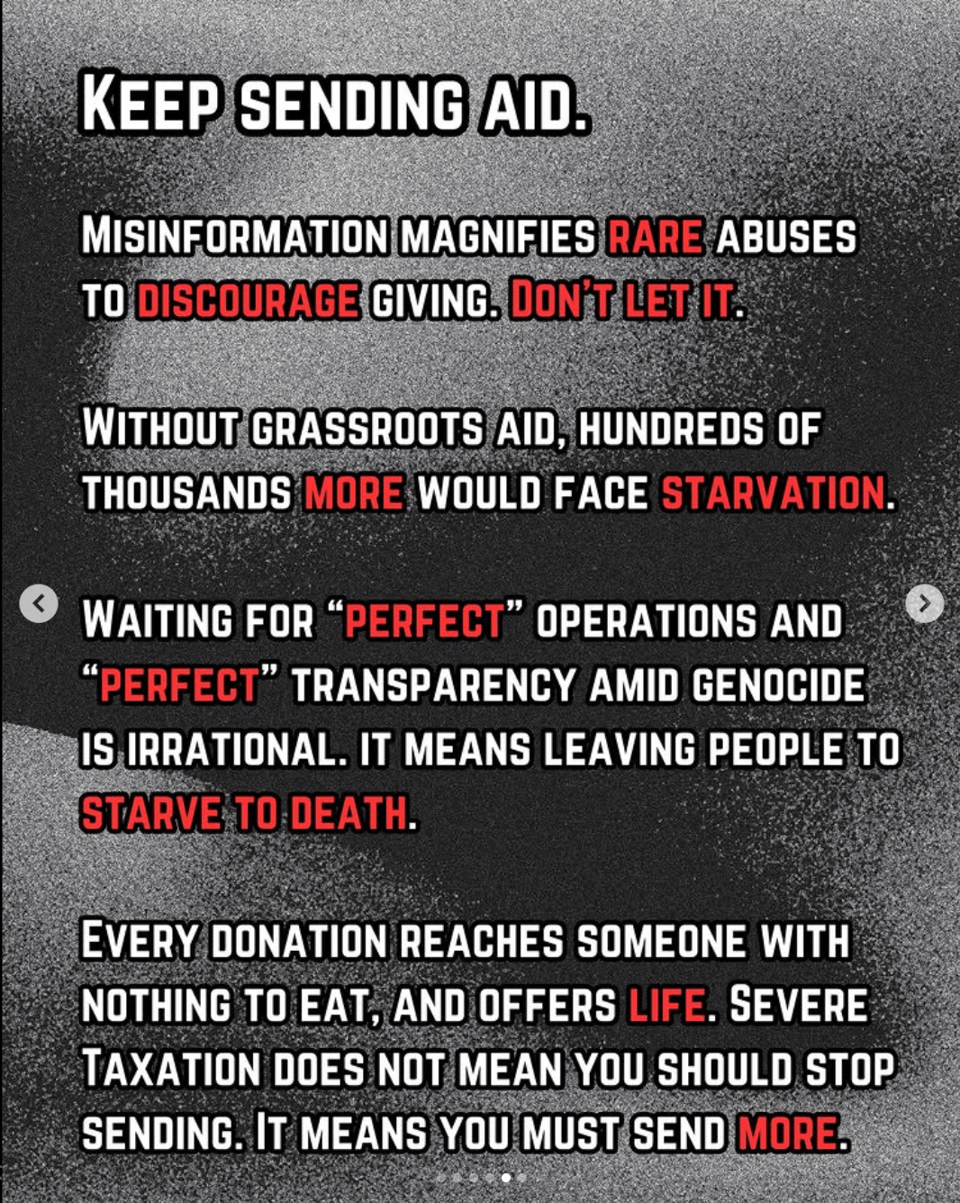

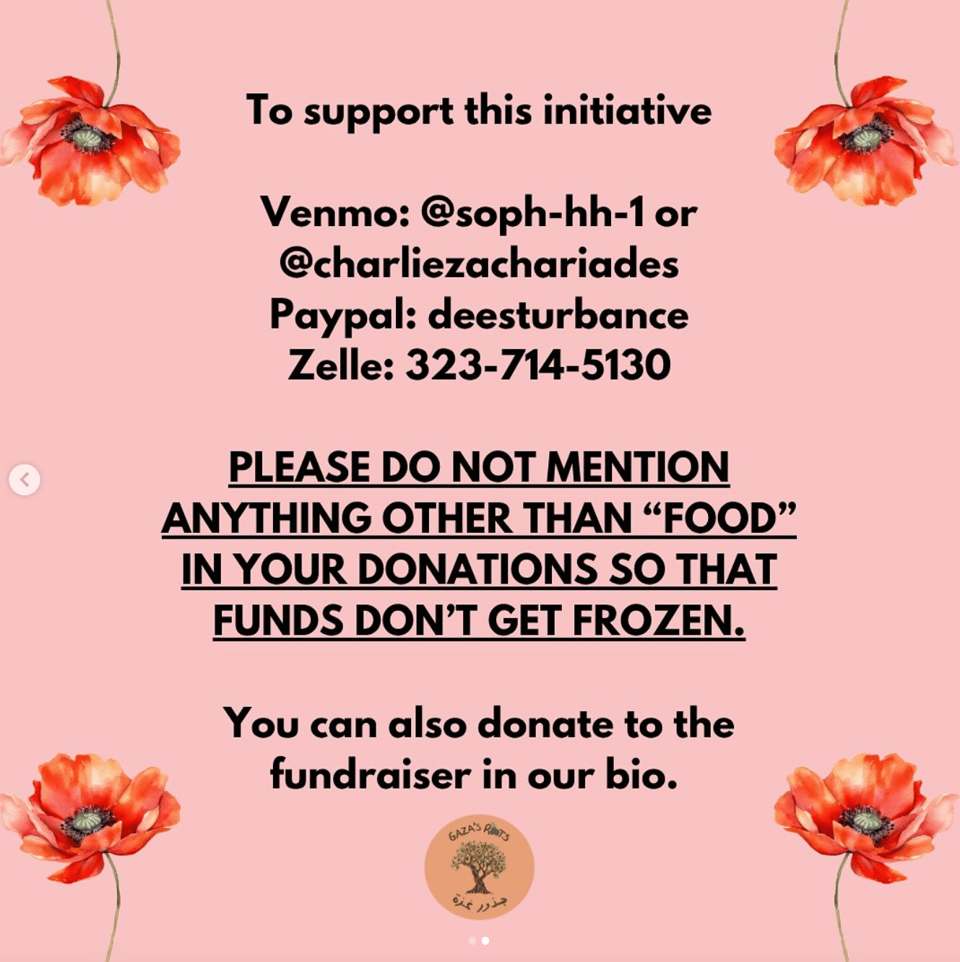

This thread on Instagram was helpful for me in understanding how best to provide financial support right now to Palestinians trying to survive the genocide.

via @gazasroots I recently redistributed money to Gaza’s Roots’ Gaza Food Program. You can find out more about their work on Instagram @gazasroots, and also via their Chuffed page.

via @gazasroots